I have said all I can to the individual arguments of the prosecution during the course of the trial and the interrogation. I shall not repeat myself, therefore, but I will summarize my point of view: I believe that the charges against me of incitement and obstruction of the exercise of duty of a public official have not been proven. I consider myself to be innocent and ask to be released.

In conclusion, however, I would like to speak out on one aspect of the whole case, which has not as yet been mentioned. During the prosecution, it was claimed that I attempted to conceal the real antistate and the antisocialist nature of an organized gathering of people. This claim, which, by the way, is not and cannot be substantiated, suggests that I acted with a political goal in mind. That surely entitles me to deal for a moment with the political side of the whole case.

Firstly, I must say that the words “antistate” and “antisocialist” lost any semantic meaning long ago, since during their long years of quite wanton use, they became a pejorative label for all citizens who, for various reasons, made the government feel uncomfortable. By that, I am not referring to their political thinking. In fact, three general secretaries of the Communist party of Czechoslovakia—Slánský, Husák, and Dubcek—have at various stages in their lives been labeled with these words. Today it is Charter 77 and other independent groups that are marked by these epithets, naturally only because the government does not like the influence they wield and because it feels the need to somehow get rid of them. As has been seen, not even my indictment has avoided this purely linguistic means of political defamation.

What then is the real political significance of what we do? Charter 77 came into being and functions as an informal society that tries to monitor Czechoslovakia’s safeguarding of human rights and the government’s adherence to international treaties and the Czechoslovak constitution. For twelve years now, Charter 77 has been drawing the government’s attention to the serious discrepancies between their obligations and social practice; for twelve years we have been pointing out various unsalutary occurrences and crises, violations of constitutional rights, arbitrariness, disorder, and incompetence. The work that Charter 77 carries out corresponds to the opinions of a considerable section of our society; I am convinced of this daily. For twelve years now, we have been offering the government dialogue on these matters. For twelve years, the government has not reacted to our initiative; it has merely imprisoned and persecuted us for it. In fact, the government itself today admits to numerous problems that Charter 77 has been indicating for a number of years and that could have been solved long ago if it had paid heed to what was said. Charter 77 has always stressed its policy of nonviolence and the lawfulness of its work. Its policy has never been to organize disturbances on the streets, and this still applies.

More than once I have publicly drawn attention to the fact that the measure of respect shown to nonconformist and critical citizens is an indicator of the measure of respect toward public opinion in general. Many times I have said that the continuing lack of respect for peaceful expressions of public opinion may in the end arouse increasingly more perceptible and emphatic protests by society. Many times I have said that it will be of help to no one if the government continues to wait until the people begin to demonstrate and go on strike; that can easily be prevented by a businesslike dialogue and the good will to listen to even those voices that are critical.

These warnings were ignored. As a result, the current rulers are now reaping the rewards of their own arrogant attitude.

I must confess to one thing. On Monday January 16 I wanted to leave Wenceslas Square immediately after the flowers had been placed by the statue of St. Wenceslas in remembrance of Jan Palach. In the end, I stayed at the Square for over an hour mostly because I simply could not believe my eyes. Something that I could not have imagined in my wildest dreams had happened. The totally unwarranted action by the police against those who wished, quietly and without any publicity, to lay flowers at the statue, immediately transformed quite coincidental passers-by into a protesting crowd. I suddenly realized the depth of civic discontent if such a thing could come to pass.

The council for the prosecution has quoted my statement, addressed to the authorities, saying that the situation is serious. I even told our representatives that the situation is more serious than they think. On January 16 I suddenly realized that the situation was more serious than I myself had thought.

Advertisement

As a citizen interested in seeing this country prosper in peace, I firmly believe the authorities will finally draw a lesson from what has happened and initiate a dignified dialogue with all sections of society, without excluding anybody from participating in this dialogue by labeling him/her “antisocialist.” I firmly believe the authorities will finally cease treating the independent groups as though they were an ugly girl smashing the mirror because she thinks it is to blame for her appearance. This is why I also firmly believe I will not be unjustifiably sentenced again.

I do not consider myself guilty. There is therefore nothing to be sorry for. If I am punished, I will accept my punishment in a spirit of sacrifice for the benefit of a good cause. Such a sacrifice however is negligible in light of the absolute sacrifice of Jan Palach, whose anniversary we wished to commemorate.

The above document was made available by Palach Press.

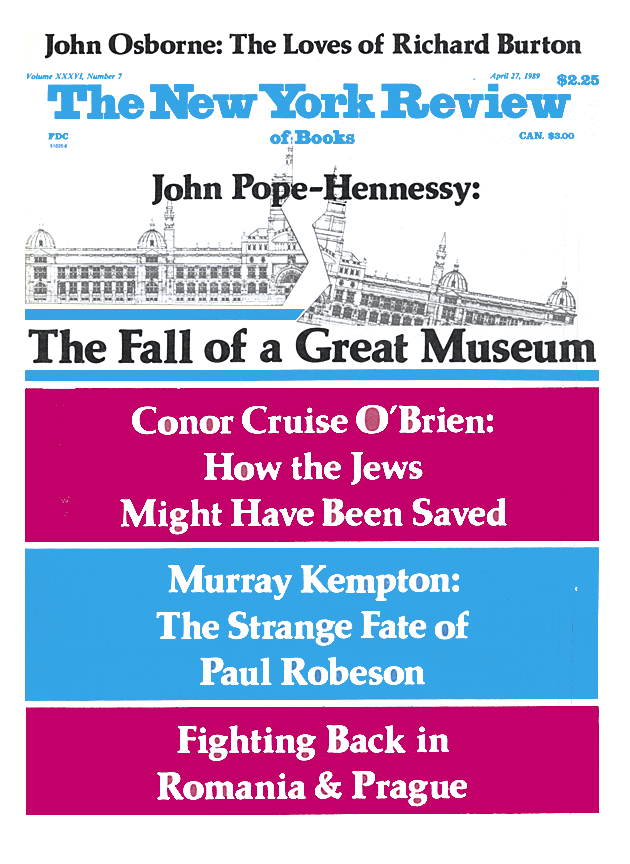

This Issue

April 27, 1989