1.

Mr. Robert Calder has written a biography of W. Somerset Maugham in order to redress, nicely, I think, some recent studies of the man who was probably our century’s most popular novelist as well as the most successful of Edwardian playwrights. Maugham’s last biographer, Mr. Ted Morgan, concentrated morbidly on the incontinences and confusions of a mad old age while scanting works and bright days. Doubtless, he was influenced by the young Maugham’s remark:

I cannot understand why a biographer, having undertaken to give the world details of a famous man’s life, should hesitate, as so often happens, to give details of his death…. Our lives are conditioned by outer circumstances but our death is our own.

Not, as it proves, with Mr. Morgan on the case. But then, as demonstrated by Mr. Morgan and other biographers of known sexual degenerates (or merely suspected—Lennon, Presley, by one A. Goldman, the master of that expanding cottage industry, Bioporn), a contemptuous adversarial style seems to be the current…norm. Despite the degenerate’s gifts, he is a Bad Person; worse, he is Immature; even worse, he is Promiscuous. Finally, he is demonstrably more Successful than his biographer, who is Married, Mature, Monogamous, and Good.

Although Mr. Calder is MMM&G, he does believe that

Morgan’s antipathy to the man is most damaging. Though his treatment of Maugham’s homosexuality is more explicit than anything previously published, it always emphasizes the nasty procuring side of his homosexual life.

Yet even a gentle schoolteacher in Saskatchewan like Mr. Calder must know that the men of Maugham’s generation paid for sex with men or women or both (the last century was prostitution’s Golden Age—for the buyer, of course). Would Mr. Calder think it relevant to note and deplore as immature Joseph Conrad’s visits to women prostitutes? I doubt it. Obviously a double standard is at work here. What is sheer high animal spirits in the roaring boy who buys a pre-feminist girl is vileness in the roaring boy who buys another boy.

To Mr. Calder’s credit, he does his best to show the amiable side to the formidable Mr. Maugham—the side that Mr. Calder terms “Willie,” as he was known to friends. But our schoolteacher also distances himself from “nastiness” in his acknowledgments where he notes “the unqualified encouragement of my parents, and my children—Alison, Kevin, Lorin, and Dani.” (Did they pipe “What’s rough trade, Daddy?” with unqualified encouragement?) No matter. By and large, children, your Daddy has done the old fruitcake proud.

Maugham spent his first twenty-six years in the nineteenth century and for the subsequent sixty-five years he was very much a nineteenth-century novelist and playwright. In many ways he was fortunately placed, though he himself would not have thought so. He was born in Paris where his lawyer father did legal work for the British Embassy, and his mother was a popular figure in Paris society. Maugham’s first language was French and although he made himself into the premier English storyteller, his prose has always had a curious flatness to it, as if it wanted to become either Basic English or Esperanto or perhaps go back into French.

Maugham’s self-pity, which was to come to a full rather ghastly flowering in Of Human Bondage, is mysterious in origin. On the demerit side, he lost a beloved mother at eight; lost three older brothers to boarding school (all became lawyers and one Lord Chancellor); lost, at eleven, a not-so-well-loved father. He was then sent off to a clergyman uncle in Whitstable—home of the oyster—and then to the standard dire school of the day. On the credit side, under his father’s will, he got 150 pounds a year for life, enough to live on. He was well-connected in the professional upper middle class. He had the run of his uncle’s considerable library—the writer’s best education. When he proved to be sickly, he was sent to the south of France; when, at seventeen, he could endure his school no more, he was sent to Heidelberg and a merry time.

On balance, the tragic wound to which he was to advert throughout a long life strikes me as no more than a scratch or two. Yes, he wanted to be taller than five foot seven; yes, he had an underslung jaw that might have been corrected; yes, he stammered. But…tant pis, as he might have observed coldly of another (used in a novel, the phrase would be helpfully translated).

Yet something was gnawing at him. As he once observed, sardonically, to his nephew Robin Maugham, “Jesus Christ could cope with all the miseries I have had to contend with in life. But then, Jesus Christ had advantages I don’t possess.” Presumably, Jesus was a six-foot-tall blond blue-eyed body-builder whereas Maugham was slight and dark with eyes like “brown velvet”; and, of course, Jesus’ father owned the shop. On the other hand, Maugham was not obliged to contend with the sadomasochistic excitement of the Crucifixion, much less the head-turning rapture of the Resurrection. It is the common view of Maugham biographers that the true tragic flaw was homosexuality, disguised as a club foot in Of Human Bondage—or was that the stammer? Whatever it was, Maugham was very sorry for himself. Admittedly, a liking for boys at the time of Oscar Wilde’s misadventures was dangerous but Maugham was adept at passing for MMM&G: he appeared to have affairs with women, not men, and he married and fathered a daughter. There need not have been an either/or for him.

Advertisement

Maugham’s career as a writer was singularly long and singularly successful. The cover of each book was adorned with a Moorish device to ward off the evil eye: the author knew that too much success overexcites one’s contemporaries, not to mention the gods. Also, much of his complaining may have been prophylactic: to avert the furies if not the book-chatterers, and so he was able to live just as he wanted for two thirds of his life, something not many writers—or indeed anyone else—ever manage to do.

At eighteen, Maugham became a medical student at St. Thomas’s Hospital, London. This London was still Dickens’s great monstrous invention where

The messenger led you through the dark and silent streets of Lambeth, up stinking alleys and into sinister courts where the police hesitated to penetrate, but where your black bag protected you from harm.

For five years Maugham was immersed in the real world, while, simultaneously, he was trying to become a writer. “Few authors,” Mr. Calder tells us, “read as widely as Maugham and his works are peppered with references to other literature.” So they are—peppered indeed—but not always seasoned. The bilingual Maugham knew best the French writers of the day. He tells us that he modelled his short stories on Maupassant. He also tells us that he was much influenced by Ibsen, but there is no sign of that master in his own school of Wilde comedies. Later, he was awed by Chekhov’s stories but, again, he could never “use” that master because something gelled very early in Maugham the writer, and once his own famous tone was set it would remain perfectly pitched to the end.

In his first published novel, Liza of Lambeth (1897), Maugham raised the banner of Maupassant and the French realists but the true influence on the book and its method was one Arthur Morrison, who had made a success three years earlier with Tales of Mean Streets. Mr. Calder notes that Morrison,

writing with austerity and frankness,…refused to express sympathy on behalf of his readers so that they could then avoid coming to terms with the implications of social and economic inequality. Maugham adopted this point of view in his first novel, and was therefore, like Morrison, accused of a lack of conviction.

In general realists have always been open to the charge of coldness, particularly by romantics who believe that a novel is essentially a sermon, emotional and compassionate and so inspiring that after the peroration, the reader, wiser, kinder, bushier indeed, will dry his eyes and go forth to right wrong. This critical mindset has encouraged a great deal of bad writing. The unemotional telling of a terrible story is usually more effective than the oh, by the wind-grieved school of romantic (that is, self-loving) prose. On the other hand, the plain style can help the dishonest, pusillanimous writer get himself off every kind of ideological or ethical hook. Just the facts, ma’am. In this regard, Hemingway, a literary shadow self to Maugham, was our time’s most artful dodger, all busy advancing verbs and stony nouns. Surfaces coldly rendered. Interiors unexplored. Manner all.

For someone of Maugham’s shy, highly self-conscious nature (with a secret, too) the adoption of classic realism, Flaubert with bitters, was inevitable. Certainly, he was lucky to have got the tone absolutely right in his first book, and he was never to stray far from the appearance of plain story-telling. Although he was not much of one for making up things, he could always worry an anecdote or bit of gossip into an agreeable narrative. Later, as the years passed, he put more and more effort—even genius—into his one triumphant creation, W. Somerset Maugham, world-weary world-traveler, whose narrative first person became the best-known and least wearisome in the world. At first he called the narrator “Ashenden” (a name carefully chosen so that the writer would not stammer when saying it, unlike that obstacle course for stammerers, “Maugham”); then he dropped Ashenden for Mr. Maugham himself in The Razor’s Edge (1944). Then he began to appear, as narrator, in film and television dramatizations of his work. Thus, one of the most-read novelists of our time became widely known to those who do not read.

Advertisement

Shaw and Wells invented public selves for polemical reasons, while Mark Twain and Dickens did so to satisfy a theatrical need, but Maugham contrived a voice and a manner that not only charm and surprise in a way that the others did not, but where they were menacingly larger than life, he is just a bit smaller (5′ 7″), for which he compensates by sharing with us something that the four histrionic masters would not have dreamed of doing: inside gossip. It is these confidences that made Maugham so agreeable to read: nothing, he tells us with a smile, is what it seems. That was his one trick, and it seldom failed. Also, before D.H. Lawrence, Dr. Maugham (obstetrician) knew that women, given a fraction of a chance, liked sex as much as men did. When he said so, he was called a misogynist.

In October 1907, at thirty-three, Maugham became famous with the triumphant production of Lady Frederick (one of six unproduced plays that he had written). Maugham ravished his audience with the daring trick of having the eponymous lady—middle-aged with ardent unsuitable youthful admirer—save the boy from his infatuation by allowing him to see her un-made-up at her dressing table. So stunned is the lad by the difference between the beauty of the maquillage and the crone in the mirror that he is saved by her nobleness, and right before our eyes we see “nothing is what it seems” in spades, raw stuff for the theater of those days.

By 1908 Maugham had achieved the dream of so many novelists: he had four plays running in the West End and he was financially set for life. In that same year, the sixty-five-year-old impecunious Henry James was having one last desperate go at the theater. To Edith Wharton he wrote that he was

working under a sudden sharp solicitation (heaven forgive me!) for the Theatre & that I had, as a matter of life or death, to push through with my play, or rather with my 2 plays (for I’m doing two), the more important of which (though an object little cochonnerie even it, no doubt!) is to be produced…. I have been governed by the one sordid & urgent consideration of the possibility of making some money…. Forgive so vulgar a tale—but I am utterly brazen about it; for my basic motive is all of that brassy complexion—till sicklied o’er with the reflection of another metal.

But it was to Maugham, not the Master, that the other metal came.

Maugham enjoyed his celebrity; he was a popular diner-out; he was, when he could get the words out, something of a wit. He was eminently marriageable in Edwardian eyes. So which will it be—the lady or the tiger/man? Mr. Calder cannot get enough of Maugham the faggot in conflict with Maugham the potential MMM&G. Will the good drive out evil? Maturity immaturity?

Unhappily, the witch-doctor approach to human behavior still enjoys a vogue in academe and Mr. Calder likes to put his subject on the couch, while murmuring such Freudian incantations as “loss of a beloved mother, the lack of a father with whom to identify…follow a common pattern in the development of homosexuality.” That none of this makes any sense does not alter belief: in matters of faith inconvenient evidence is always suppressed while contradictions go unnoticed. Nevertheless, witch doctors to one side, witches did—and do—get burned, as Oscar Wilde discovered in 1895, and an entire generation of same-sexers were obliged to go underground or marry or settle in the south of France. I suspect that Maugham’s experiences with women were not only few but essentially hydraulic. Writers, whether same-sexers or other-sexers, tend to have obsessive natures; in consequence they cross the sexual borders rather less often than the less imaginative who want, simply, to get laid or even loved. But whereas a same-sexer like Noel Coward never in his life committed an other-sexual act (“Not even with Gertrude Lawrence?” I asked. “Particularly not with Miss Lawrence” was the staccato response), Dr. Maugham had no fear of vaginal teeth—he simply shut his eyes and thought of Capri.

At twenty-one Maugham was well and truly launched by one John Ellingham Brooks, a littérateur who lived on Capri, then known for the easy charm of its boys. “The nasty procuring side” of Maugham started in Capri and he kept coming back year after year. At ninety, he told a reporter, “I want to go to Capri because I started life there.” In old age, he told Glenway Westcott that Brooks was his first lover. This is doubtful. Maugham told different people different things about his private life, wanting always to confuse. Certainly, for sheer energetic promiscuity he was as athletic as Byron; with a club foot, what might he not have done! Even so, “He was the most sexually voracious man I’ve ever known,” said Beverly Nichols, the journalist and one-time Maugham secretary, who knew at first hand. Robin Maugham and the last companion, Alan Searle, agreed.

Ironically, within a dozen years of Wilde’s imprisonment, Maugham was the most popular English playwright. Unlike the reckless Oscar, Maugham showed no sign of ever wanting to book so much as a room at the Cadogan Hotel. Marriage it would be. With Syrie Barnardo Wellcome, an interior decorator much liked in London’s high bohemia. Fashionable wife for fashionable playwright. A daring woman of the world—an Iris March with a green hat pour le sport, Syrie wanted a child by Maugham without wedlock. Got it. As luck—hers and his—would have it, Maugham then went to war and promptly met the great love of his life, Gerald Haxton.

For a time Maugham was a wound dresser. Gerald was in the Ambulance Corps. They were to be together until Gerald’s death twenty-nine years later, “longer than many marriages.” observes the awed Mr. Calder. But there was a good deal of mess to be cleaned up along the way. Haxton could not go to England: he had been caught by the police in bed with another man. Maugham himself did not want, finally, to be even remotely MMM&G. Syrie suffered. They separated. Toward the end of his life, Maugham tried to disinherit his daughter on the ground that she was not his but, ironically, he had got a door prize for at least one dutiful attendance and she was very much his as anyone who has ever seen her or her descendants can attest: the saturnine Maugham face still gazes by proxy upon a world where nothing is ever what it seems.

During the war, Maugham was hired by the British secret service to go to Moscow and shore up the Kerensky government. He has written of all this in both fiction (Ashenden—literary ancestor to Eric Ambler, Ian Fleming, John le Carré) and two books of memoirs. Unfortunately, the mission to Moscow was aborted by the overthrow of Kerensky.

Maugham developed tuberculosis. During twenty months in a Scottish sanitarium he wrote four of his most popular plays, including The Circle and the highly successful novel The Moon and Sixpence, where a Gauguin-like English painter is observed by the world-weary Ashenden amongst Pacific palms. Maugham wrote his plays rather the way television writers (or Shakespeare) write their serials—at great speed. One week for each act and a final week to pull it all together. Since Mr. Calder is overexcited by poor Willie’s rather unremarkable (stamina to one side) sex life, we get far too little analysis of Maugham’s writing and of the way that he worked, particularly in the theater. From what little Mr. Calder tells us, Maugham stayed away from rehearsals but, when needed, would cut almost anything an actor wanted. This doesn’t sound right to me but then when one has had twenty play productions in England alone, there is probably not that much time or inclination to perfect the product. In any case, Mr. Calder is, as he would put it, “disinterested” in the subject.

In 1915, while Maugham was spying for England. Of Human Bondage was published. Maugham now was seen to be not only a serious but a solemn novelist—in the ponderous American manner. The best that can be said of this masterpiece is that it made a good movie and launched Bette Davis’s career. I remember that on all the pre–Second War editions, there was a quotation from Theodore Dreiser to the effect that the book “has rapture, it sings.” Mr. Calder does not mention Dreiser but Mr. Frederic Raphael does, in his agreeable picture book with twee twinkly text, Somerset Maugham and His World.1 Mr. Raphael quotes from Dreiser, whom he characterizes as “an earnest thunderer in the cause of naturalism and himself a Zolaesque writer of constipated power.” Admittedly, Dreiser was not in a class with Margaret Drabble but—constipated?

The Maugham persona was now perfected in life and work. Maugham’s wit was taken for true evil as he himself was well known, despite all subterfuge, to be non-MMM&G. Mr. Calder is disturbed by Maugham’s attempts at epigrams in conversation. Sternly, Mr. Calder notes: “Calculated flippancy was none the less a poor substitute for natural and easy insouciance.” But despite a near-total absence of easy insouciance, Maugham fascinated everyone. By 1929 he had settled into his villa at Cap Ferrat; he was much sought after socially even though the Windsors, the Churchills, the Beaverbrooks all knew that Haxton was more than a secretary. But the very rich and the very famous are indeed different from really real folks. For one thing, they often find funny the MMM&Gs. For another, they can create their own world and never leave it if they choose.

It is a sign of Maugham’s great curiosity and continuing sense of life (even maturity) that he never stopped traveling, ostensibly to gather gossip and landscapes for stories, but actually to come alive and indulge his twin passions, boys and bridge, two activities far less damaging to the environment than marriages, children, and big-game hunting. Haxton was a splendid organizer with similar tastes. Mr. Calder doesn’t quite get all this but then his informants, chiefly nephew Robin Maugham and the last companion, Alan Searle, would have been discreet.

During the Second War, Maugham was obliged to flee France for America. In Hollywood he distinguished himself on the set of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. George Cukor had explained to Willie how, in this version of the Stevenson story, there would be no horrendous makeup change for the star, Spencer Tracy, when he turned from good Dr. Jekyll into evil Mr. Hyde. Instead, a great actor, Tracy, would bring forth both evil and good from within. Action! Tracy menaces the heroine. Ingrid Bergman cowers on a bed. Tracy simpers, drools, leers. Then Maugham’s uneasy souciant voice is heard, loud and clear and stammerless. “And which one is he supposed to be now?”

During this time, the movie of The Moon and Sixpence was released—the twenty-third Maugham story to be filmed. Maugham himself traveled restlessly about the East coast, playing bridge. He also had a refuge in North Carolina where, while writing The Razor’s Edge, Haxton died. For a time Maugham was inconsolable. Then he took on an amiable young Englishman, Alan Searle, as secretary-companion, and together they returned to the Riviera where Maugham restored the war-wrecked villa and resumed his life.

One reason, prurience aside, why Mr. Calder tells us so much about Maugham’s private life (many kindnesses and charities are duly noted) is that Maugham has no reputation at all in North American academe where Mr. Calder is a spear-carrier. The result is a lot of less than half-praise:

His career had been largely a triumph of determination and will, the success in three genres of a man not naturally gifted as a writer.

Only a schoolteacher innocent of how literature is made could have written such a line. Demonstrably, Maugham was very talented at doing what he did. Now, this is for your final grade, what did he do? Describe, please. Unfortunately, there aren’t many good describers (critics) in any generation. But I shall give it a try, presently.

At seventy-two, Maugham went to Vevey, Switzerland, where a Dr. Niehans injected aging human organisms with the cells of unborn sheep, and restored youth. All the great and not-so-good came to Niehans, including Pius XII—in a business suit and dark glasses, it was said—an old man in no hurry to meet his Jewish employer. Thanks perhaps to Niehans, Maugham survived for nearly fifteen years in rude bodily health. But body outlived mind and so it was that the senile Maugham proceeded to destroy his own great invention, W. Somerset Maugham, the teller of tales, the man inclined to the good and to right action, and above all, to common sense. By the time that old Maugham had finished with himself, absolutely nothing was what it seemed and the double self-portrait that he had given the world in The Summing Up and A Writer’s Notebook was totally undone by this raging Lear upon the Riviera, who tried to disinherit daughter while adopting Searle as well as producing Looking Back, a final set of memoirs not quite as mad as Hemingway’s but every bit as malicious. With astonishing ingenuity, the ancient Maugham mined his own monument; and blew it up.

For seven decades Maugham had rigorously controlled his personal and his artistic life. He would write so many plays, and stop; and did. So many novels, and stop; and did. So many short stories…. He rounded off everything neatly, and lay back to die, with a quiet world-weary smile on those ancient lizard lips. But then, to his horror, he kept on living, and having sex, and lunching with Churchill and Beaverbrook. Friends thought that Beaverbrook put him up to the final memoir, but I suspect that Maugham had grown very bored with a lifetime of playing it so superbly safe.

2.

It is very difficult for a writer of my generation, if he is honest, to pretend indifference to the work of Somerset Maugham. He was always so entirely there. By seventeen I had read all of Shakespeare; all of Maugham. Perhaps more to the point, he dominated the movies at a time when movies were the lingua franca of the world. Although the French have told us that the movie is the creation of the director, no one in the Twenties, Thirties, Forties paid the slightest attention to who had directed Of Human Bondage, Rain, The Moon and Sixpence, The Razor’s Edge, The Painted Veil, The Letter. Their true creator was W. Somerset Maugham, and a generation was in thrall to his sensuous, exotic imaginings of a duplicitous world.

Although Maugham received a good deal of dutiful praise in his lifetime, he was never to be taken very seriously in his own country or the United States, as opposed to Japan where he has been for two thirds of a century the most read and admired Western writer. Christopher Isherwood tells us that he met Maugham at a Bloomsbury party where Maugham looked most ill at ease with the likes of Virginia Woolf. Later Isherwood learned from a friend of Maugham’s that before the party, in an agony of indecision, as the old cliché master might have put it, he had paced his hotel sitting room, saying, “I’m just as good as they are.”

I suspect that he thought he was probably rather better for what he was, which was not at all what they were. Bloomsbury disdained action and commitment other than to Art and to Friendship (which meant going to bed with one another’s husbands and wives). Maugham liked action. He risked his life in floods, monsoons, the collapse of holy Russia. He was worldly like Hemingway, who also stalked the big game of wild places, looking for stories, self. As for what he thought of himself, Mr. Calder quotes Maugham to the headmaster of his old school: “I think I ought to have the O.M. [Order of Merit]…. They gave Hardy the O.M. and I think I am the greatest living writer of English, and they ought to give it to me.” When he did get a lesser order, Companion of Honour, he was sardonic: “It means very well done…but.”

But. There is a definite but. I have just reread for the first time in forty years The Narrow Corner, a book I much admired; The Razor’s Edge, the novel on which the film that I found the ultimate in worldly glamour was based; A Writer’s Notebook, which I recalled as being very wise; and, yet again, Cakes and Ale. Edmund Wilson’s famous explosion at the success of Maugham in general and The Razor’s Edge in particular is not so far off the mark:

The language is such a tissue of clichés that one’s wonder is finally aroused at the writer’s ability to assemble so many and at his unfailing inability to put anything in an individual way.

Maugham’s reliance on the banal, particularly in dialogue, derived from his long experience in the theater, a popular art form in those days. One could no more represent the people on stage without clichés than one could an episode of Dynasty: Maugham’s dialogue is a slightly sharpened version of that of his audience.

Both Wilde and Shaw dealt in this same sort of realistic speech but Shaw was a master of the higher polemic (as well as of the baleful clichés of the quaint workingman, rendered phonetically to no one’s great delight) while Wilde made high verbal art of clichés so slyly crossed as to yield incongruent wit. But for any playwright of that era (now, too), the mot juste was apt to be the well-deployed mot banal. Maugham’s plays worked very well. But when Maugham transferred the tricks of the theater to novel writing, he was inclined to write not only the same sort of dialogue that the stage required but in his dramatic effects he often set his scene with stage directions, ignoring the possibilities that prose with dialogue can yield. This economy won him many readers, but there is no rapture, song. Wilson, finally, puts him in the relation of Bulwer-Lytton to Dickens: “a half-trashy novelist who writes badly, but is patronized by half-serious readers who do not care much about writing.” What ever happened to those readers? How can we get them back?

Wilson took the proud modernist view that, with sufficient education, everyone would want to move into Axel’s Castle. Alas, the half-serious readers stopped reading novels long ago while the “serious” read literary theory, and the castle’s ruins are the domain of literary archaeologists. But Wilson makes a point, inadvertently: If Maugham is half-trashy (and at times his most devoted admirers would probably grant that) what, then, is the other half, that is not trash? Also, why is it that just as one places, with the right hand, the laurel wreath upon his brow, one’s left hand starts to defoliate the victor’s crown?

A Writer’s Notebook (kept over fifty years) is filled with descriptions of sunsets and people glimpsed on the run. These descriptions are every bit as bad as Wilson’s (in The Twenties) and I don’t see why either thought that writing down a fancy description of a landscape could—or should—be later glued to the page of a novel in progress. Maugham’s descriptions, like Wilson’s, are disagreeably purple while the physical descriptions of people are more elaborate than what we now put up with. But Maugham was simply following the custom of nineteenth-century novelists in telling us whether or not eyebrows grow together while noting the exact placement of a wen. Also, Dr. Maugham’s checklist is necessary for diagnosis. Yet he does brood on style; attempts to make epigrams. “Anyone can tell the truth, but only very few of us can make epigrams.” Thus, young Maugham, to which the old Maugham retorts, “In the nineties, however, we all tried to.”

In the preface, Maugham expatiates on Jules Renard’s notebooks, one of the the great delights of world literature and, as far as I can tell, unknown to Anglo-Americans, like so much else. Renard wrote one small masterpiece, Poil de Carotte, about his unhappy childhood—inhuman bondage to an evil mother rather than waitress.

Renard appeals to Maugham, though “I am always suspicious of a novelist’s theories, I have never known them to be anything other than a justification of his own shortcomings.” Well, that is commonsensical. In any case, Maugham, heartened by Renard’s marvelous notebook, decided to publish his own. The tone is world-weary, modest. “I have retired from the hurly-burly and ensconced myself not uncomfortably on the shelf.” Thus, he will share his final musings.

There is a good deal about writing. High praise for Jeremy Taylor:

He seems to use the words that come most naturally to the mouth, and his phrases, however nicely turned, have a colloquial air…. The long clauses, tacked on to one another in a string that appears interminable, make you feel that the thing has been written without effort.

Here, at twenty-eight, he is making the case for the plain and the flat and the natural sounding:

There are a thousand epithets with which you may describe the sea. The only one which, if you fancy yourself a stylist, you will scrupulously avoid is blue; yet it is that which most satisfies Jeremy Taylor…. He never surprises. His imagination is without violence or daring.

Of Matthew Arnold’s style, “so well suited to irony and wit, to exposition…. It is a method rather than an art, no one more than I can realize what enormous labour it must have needed to acquire that mellifluous cold brilliance. It is a platitude that simplicity is the latest acquired of all qualities….” The interesting giveaway here is Maugham’s assumption that Arnold’s style must have been the work of great labor. But suppose, like most good writers, the style was absolutely natural to Arnold and without strain? Here one sees the hard worker sternly shaping himself rather than the natural writer easily expressing himself as temperament requires:

My native gifts are not remarkable, but I have a certain force of character which has enabled me in a measure to supplement my deficiencies. I have common sense…. For many years I have been described as a cynic; I told the truth. I wish no one to take me for other than I am, and on the other hand I see no need to accept others’ pretenses.

One often encounters the ultimate accolade “common sense” in these musings. Also, the conceit that he is what you see, when, in fact, he is not. For instance, his native gifts for narrative were of a very high order. While, up to a point, he could tell the truth and so be thought cynical, it was always “common sense,” a.k.a. careerism, that kept him from ever saying all that he knew. Like most people, he wanted to be taken for what he was not; hence, the great invention W. Somerset Maugham.

Maugham uses his Moscow experience to good literary advantage. He reads the Russians. Marvels at their small cast of characters. Notes that no one in a Russian book ever goes to an art gallery. Later, he travels through America, wondering what the people on the trains are really like. Then he reads, with admiration, Main Street, where he detects the emergence of a complex caste system and,

The lip service which is given to equality occasions a sort of outward familiarity, but this only makes those below more conscious of the lack of inward familiarity; and so nowhere is class-hatred likely to give rise in the long run to more bitter enmity.

Maugham was alert to the ongoing problem of how to be a writer at all: certainly the writer “must never entirely grow up…. It needs a peculiar turn of mind in a man of fifty to treat with great seriousness the passion of Edwin for Angelina.” Or Edmund for Daisy. “The novelist is dead in the man who has become aware of the triviality of human affairs. You can often discern in writers the dismay with which they have recognized this situation in themselves.” He notes how Flaubert turned from Madame Bovary to Bouvard et Pécuchet, George Eliot and H.G. Wells to “sociology,” Hardy to The Dynasts—a step farther up Parnassus but no one thought so then.

Maugham’s great enthusiasm is for Chekhov, a fellow doctor, playwright, and short-story writer:

He has been compared with Guy de Maupassant, but one would presume only by persons who have read neither. Guy de Maupassant is a clever story-teller, effective at his best—by which, of course, every writer has the right to be judged—but without much real relation to life…. But with Chekhov you do not seem to be reading stories at all. There is no obvious cleverness in them and you might think that anyone could write them, but for the fact that nobody does. The author has had an emotion and he is able so to put it in words that you receive it in your turn. You become his collaborator. You cannot use of Chekhov’s stories the hackneyed expression of the slice of life, for a slice is a piece cut off and that is exactly the impression you do not get when you read them; it is a scene seen through the fingers which you know continues this way and that though you only see a part of it.

Mr. Maugham knows very well what literature is, and how great effects are, if not made, received.

Finally, he makes a bit of literature in one of the notebook entries. A popular writer of the day, Haddon Chambers, is dead. He is known for one phrase, “the long arm of coincidence.” Maugham does a short amusing sketch of Chambers, the man and the writer; then he concludes:

I seek for a characteristic impression with which to leave him. I see him lounging at a bar, a dapper little man, chatting good-humouredly with a casual acquaintance of women, horses and Covent Garden opera, but with an air as though he were looking for someone who might at any moment come in at the door.

That is very fine indeed, and Mr. Chambers still has a small corner of life in that bar, in that paragraph.

My only memory of The Razor’s Edge (1944) was that of an American lady who threw a plate at the narrator, our own Mr. Maugham, with the cry, “And you call yourself an English gentleman,” to which Mr. Maugham, played urbanely in the movie by Herbert Marshall, responded niftily, “No, that’s a thing I’ve never done in all my life.” The scene has remained in my memory all these years because it is almost the only one in the book that has been dramatized. Everything else is relentlessly told. The first-person narrator, so entirely seductive in the short stories, is now heavy, garrulous, and awkward, while the clichés are not only “tissued” but Maugham even cocks, yes, a snook at his critics by recording every one of an American businessman’s relentless banalities. Of course the author is sixty-nine. Maugham’s view of the world was consistent throughout his life. Intrigued by religion, he remained an atheist. Vedanta was attractive, but reincarnation was simply not common sense. If you had no recollection of any previous incarnations, what was the point? For all practical purposes the first carnation was extinct when it died, and all the others random. But during the Second War there was a lot of musing about the meaning of it all, and out of that age’s anxiety did come Thomas Mann’s masterpiece, Doctor Faustus.

Maugham stalks similar game. Again, the narrator is our Mr. Maugham, the all-wise, all-tolerant Old Party who knows a thing or two. Nearby, on the Riviera, lives Elliott Templeton, an elegant snobbish old queen whose identity was revealed for the first time in these pages (September 29, 1983), Henry de Courcy May. (Mr. Calder thinks that the character is, in part, Chips Channon, but Chips is separately present as Paul Barton, another American social climber.) Elliott is an amusing character (Mr. Calder finds him “brilliant”) but Maugham can’t do very much with him other than give him a Chicago niece. And money, Paris. Love. The niece is in love with Larry Darrell—why a name so close to real life Larry Durrell? Maugham’s names for characters (like Hemingway’s) are standard for the time—highly forgettable Anglo-Saxon names. Why? Because novels were read by a very large public in those days and any but the most common of names could bring on a suit for libel.

Larry does not want to go to work, he wants to “loaf.” This means that he has spiritual longings: what does it all mean? He wants to know. He loses the girl to a wealthy young man who doesn’t care what it may or may not mean. In pursuit of it, Larry becomes very learned in Germany; he works in a coal mine; he goes to India and discovers Vedanta. He returns to the world perhaps with it or perhaps not since it is an illusion like all else.

Maugham and Larry sit up all night in a bistro while Larry tells him the entire story of his life, much of which Maugham has already told us: it is very dangerous to be your own narrator in a book. Finally, as the dawn like a frightened Scottish scone peeps through the bistro window, Larry tells and tells about India. And Vedanta.

Larry wants nothing less than Enlightenment. Does he achieve it? Maugham teases us. Yes, no, it’s all the same, isn’t it? There are several short stories intercut with Larry’s passion play: a brilliant poetic girl becomes a drunken drug-ridden hag and ends up on the Riviera and in the Mediterranean, murdered by a piece of trade. Proof to Mr. Calder and his Freudian friends that because Maugham liked males he, what else? hated females. This is one of the rocks on which the whole Freudian structure has been, well…erected. For the witch doctors, Maugham’s invention of such a woman is prima facie evidence of his hatred of the opposite sex, which vitiated his work and made it impossible for him to be truly great and married. Yet in real life it is the other-sexers (Hemingway) who hate women and the same-sexers (Maugham) who see them not as women but, as someone observed of Henry James’s response to the ladies, as people. Finally, even the most confused witchdoctor must have stumbled upon that essential law of human behavior: one cannot hate what one cannot love. Nevertheless, as members of chemistry departments still search for cold fusion, so dedicated English teachers still seek to crack the fairy code.

Depressed, I move on to The Narrow Corner. On the first page, the energy is switched on. First chapter: “All this happened a good many years ago.” That’s it. One settles in. Second chapter begins: “Dr. Saunders yawned. It was nine o’clock in the morning.” An English doctor (under a cloud in England—abortion? We are not told). He practices medicine in the Chinese port of Fu-chou. There is no Mrs. Saunders. There is a beautiful Chinese boy who prepares his opium pipes. Sentences are short. Descriptions of people are never tedious. We inhabit Dr. Saunders’s mind for most of the book though, as always, Maugham will shift the point of view to someone else if for some reason Dr. Saunders is not witness to a necessary scene. This is lazy but a lot better than having someone sit down and tell you the story of his life, in quotation marks, page after page.

Dr. Saunders is offered a great deal of money to operate on a rich Chinese opium trafficker, domiciled on the island of Takana in the distant Malay archipelago (a trip as momentous and hazardous in those days as one from Ann Arbor to East Anglia today). By page seven the trip has been made and a successful operation for cataract has been performed. Now Dr. Saunders and beautiful Chinese boy are looking for a ship to get them home again. Enter Captain Nichols, a man under numerous clouds, but a first-class English skipper. Dr. Saunders is amused by the rogue who has arrived aboard a lugger out of Sydney, destination vague. They spar. Each notes the other’s cloud. Will Dr. Saunders leave the island aboard Nichols’s boat?

Dr. Saunders was not a great reader. He seldom opened a novel. Interested in character, he liked books that displayed the oddities of human nature, and he had read over and over again Pepys and Boswell’s Johnson, Florio’s Montaigne and Hazlitt’s essays…. He read neither for information nor to improve his mind, but sought in books occasion for reverie.

In 1938, George Santayana dismissed Maugham’s stories: “They are not pleasing, they are not pertinent to one’s real interests, they are not true; they are simply plausible, like a bit of a dream that one might drop into in an afternoon nap.” Yet, perhaps, that is a necessary condition of narrative fiction, a plausible daydreaming. Although Maugham could never have read Santayana’s letter to a friend, he returns the compliment in A Writer’s Notebook:

I think Santayana has acquired his reputation in America owing to the pathetically diffident persuasion of Americans that what is foreign must have greater value than what is native…. To my mind Santayana is a man who took the wrong turning. With his irony, his sharp tongue, common-sense and worldly wisdom, his sensitive understanding, I have a notion that he could have written semi-philosophical romances after the manner of Anatole France which it would have been an enduring delight to read…. It was a loss to American literature when Santayana decided to become a philosopher rather than a novelist.

Kindly vocational guidance from Uncle Willie; or it takes one to….

The plot: aboard the lugger is an edgy young Australian beauty (this was Maugham’s one and only crypto-lag novel). Fred Blake is also under a cloud but where Doctor and Skipper each wears his cloud pour le sport, Fred seems ready to jump, as they say, out of his skin. It is finally agreed that the Doctor accompany them to one of the Dutch islands where he can find a ship for home. They embark. There is a storm at sea, not quite as well rendered as that in Williwaw, but Maugham’s influence permeates those chaste pages, even down to the annoying use of “i” and “ii” as chapter heads. Plainly, the book had a large effect on the youthful war writer.

Finally, they arrive at the Dutch island of Banda Neira. There are substantial Dutch houses with marble floors, relics of a former prosperity, as well as nutmeg trees, all the props. They encounter a noble Danish youth, Erik Christessen, who in turn introduces them to a one-time English school teacher, Frith, and his daughter, Louise. The saintly Eric is in love with beautiful Louise, who is enigmatic. Dr. Saunders sees the coming tragedy but the others are unaware, particularly the trusting Eric, who says, early on, how much he likes the East, “Everyone is so nice, Nothing is too much trouble. You cannot imagine the kindness I’ve received at the hands of perfect strangers.” I was not the only American writer to be influenced by this book.2

Fred and Louise couple for a night. Eric finds out and kills himself. Louise is sad but confesses to the doctor that she really did not love Eric, who had not been enamored so much of her as of her late mother. She is, in her quiet way, a startling character. The lugger sails away. Then Fred’s cloud is revealed: he murdered by accident the husband of an older woman who had been hounding him. As Fred’s lawyer father is a great power in the corrupt government of New South Wales (tout ça change, as we say in Egypt), Fred is whisked away by Captain Nichols. In due course, it is learned that Fred is supposed to have died in a flu epidemic. So he is now a nonperson under two clouds. Dr. Saunders leaves them. Some time later, Dr. Saunders is daydreaming in Singapore when Nichols reappears. Fred fell overboard and drowned. Apparently all his money was in his belt which so weighed him down…. Worse, he had won all of Nichols’s money at cribbage. Plainly, the doomed boy had been killed for his money which, unknown to Nichols, he took with him to Davy Jones’s locker. Nothing is….

The novel still has all of its old magic. There is not a flaw in the manner except toward the end where Maugham succumbs to sentiment. Fred:

“Erik was worth ten of her. He meant all the world to me. I loathe the thought of her. I only want to get away. I want to forget. How could she trample on that lone noble heart!” Dr. Saunders raised his eyebrows. Language of that sort chilled his sympathy. “Perhaps she’s very unhappy,” he suggested mildly.

“I thought you were a cynic. You’re a sentimentalist.”

“Have you only just discovered it?”

Sincerity in a work of art is always dangerous and Maugham, uncharacteristically, lets it mar a key scene because, by showing that boy cared more for boy than girl, he almost gives away at least one game. But recovery was swift and he was never to make that mistake again. As he himself observed in Cakes and Ale:

I have noticed that when I am most serious people are apt to laugh at me, and indeed when after a lapse of time I have read passages that I wrote from the fullness of my heart I have been tempted to laugh at myself. It must be that there is something naturally absurd in a sincere emotion, though why there should be I cannot imagine, unless it is that man, the ephemeral inhabitant of an insignificant planet with all his pain and all his striving is a jest in an eternal mind.

What then of Cakes and Ale? The story is told in the first person by the sardonic Ashenden, a middle-aged novelist (Maugham was fifty-six when the book was published in 1930). The manner fits the story, which is not told but acted out. What telling we are told is simply Maugham the master essayist, heir of Hazlitt, commenting on the literary world of his day—life, too. In this short novel he combines his strengths—the discursive essay “peppered” this time with apposite literary allusions to which is added the high craftsmanship of the plays. The dialogue scenes are better than those of any of his contemporaries while the amused comments on literary ambition and reputation make altogether enjoyable that small, now exotic, world.

Plot: a great man of letters, Edward Driffield (modeled on Thomas Hardy), is dead and the second wife wants someone to write a hagiography of this enigmatic rustic figure whose first wife had been a barmaid; she had also been a “nymphomaniac” and she had left the great man for an old lover. The literary operator of the day, Alroy Kear (Maugham’s portrait spoiled the rest of poor Hugh Walpole’s life), takes on the job. Then Kear realizes that Ashenden knew Driffield and his first wife, Rosie. When Ashenden was a boy, they had all lived at the Kentish port, Blackstable. The first line of the book:

I have noticed that when someone asks for you on the telephone and, finding you out, leaves a message…as it’s important, the matter is more often important to him than to you. When it comes to making you a present or doing you a favour most people are able to hold their impatience within reasonable bounds.

Maugham is on a roll, and the roll continues with great wit and energy to the last page. He has fun with Kear, with Driffield, with himself, with Literature. Ashenden purrs his admiration for Kear: “I could think of no one of my contemporaries who had achieved so considerable a position on so little talent.” He commends Kear’s largeness of character. On the difficult business of how to treat those who were once equals but are now failed and of no further use at all, Kear “when he had got all he could from people…dropped them.” But Maugham is not finished:

Most of us when we do a caddish thing harbor resentment against the person we have done it to, but Roy’s heart, always in the right place, never permitted him such pettiness. He could use a man very shabbily without afterward bearing him the slightest ill-will.

This is as good as Jane Austen.

Will Ashenden help out even though it is clear that second wife and Kear are out to demonize the first wife, Rosie, and that nothing that Ashenden can tell them about her will change the game plan? Amused, Ashenden agrees to help out. He records his memories of growing up in Blackstable, of the Driffields, who are considered very low class indeed: Ashenden’s clergyman uncle forbids the boy to see them but he does. Rosie is a creature of air and fire. She is easy, and loving, and unquestioning. Does she or does she not go to be with her numerous admirers in the village and later in London where Ashenden, a medical student, sees them again (they had fled Blackstable without paying their bills)?

In London Driffield’s fame slowly grows until he becomes the Grand Old Man of Literature. Ashenden’s secret—for the purposes of the narrative—is that he, too, had an affair in London with Rosie and when he taxed her with all the others, she was serene and said that that was the way she was and that was that. As writer and moralist Maugham has now traveled from the youthful blurter-out of the truth about woman’s potential passion for sex to an acceptance that it is a very good thing indeed and what is wrong with promiscuity if, as they say, no one is hurt? In the end Rosie leaves Driffield for an old love; goes to New York, where, presumably, she and old love are long since dead.

As the narrative proceeds, Maugham has a good deal of fun with the literary world of the day, where, let us note, not one academic can be found (hence, its irrelevance?). On the subject of “longevity is genius,” he thinks old extinct volcanoes are apt to be praised as reviewers need fear their competition no longer:

But this is to take a low view of human nature and I would not for the world lay myself open to a charge of cheap cynicism. After mature consideration I have come to the conclusion that the real reason for the applause that comforts the declining years of the author who exceeds the common span is that intelligent people after thirty read nothing at all.

This auctorial self-consciousness now hurls old Maugham into the mainstream of our fin-de-siècle writing where texts gaze upon themselves with dark rapture. “As they grow older the books they read in their youth are lit with its glamour and with every year that passes they ascribe greater merit to the author that wrote them.” Well, that was then; now most intelligent readers under thirty read nothing at all that’s not assigned.

I read in the Evening Standard an article by Mr. Evelyn Waugh in the course of which he remarked that to write novels in the first person was a contemptible practise…. I wish he had explained why….

Maugham makes the modest point that with “advancing years the novelist grows less and less inclined to describe more than his own experience has given him. The first-person singular is a very useful device for this limited purpose.”

In Looking Back, Maugham “explains” his uncharacteristic portrait of a good and loving woman who gave of herself (sympathy, please, no tea) as being based on an actual woman/affair. Plainly, it is not. But his charade is harmless. What he has done is far better: he makes a brand-new character, Rosie, who appears to be a bad woman, but her “badness” is really goodness. Once again, nothing is what it seems. To the end this half-English, half-French writer was a dutiful and worthy heir to his great forebears Hazlitt and Montaigne.

Posterity? That oubliette from which no reputation returns. Maugham:

I think that one or two of my comedies may retain for some time a kind of pale life, for they are written in the tradition of English comedy…that began with the Restoration dramatists…. I think a few of my best short stories will find their way into anthologies for a good many years to come if only because some of them deal with circumstances and places to which the passage of time and the growth of civilization will give a romantic glamour. This is slender baggage, two or three plays and a dozen short stories…

But then it is no more than Hemingway, say, will be able to place in the overhead rack of the economy section of that chartered flight to nowhere, Twentieth Century Fiction.

I would salvage the short stories and some of the travel pieces, but I’d throw out the now-too-etiolated plays and add to Maugham’s luggage Cakes and Ale, a small perfect novel, and, sentimentally, The Narrow Corner. Finally, Maugham will be remembered not so much for his own work as for his influence on movies and television. There are now hundreds of versions of Maugham’s plays, movies, short stories available on cassettes, presumably forever. If he is indeed half-trashy, then one must acknowledge that the other half is of value; that is, classicus, “belonging to the highest class of citizens,” or indeed of any category; hence, our word “classic”—as in Classics and Commercials. Emphasis added.

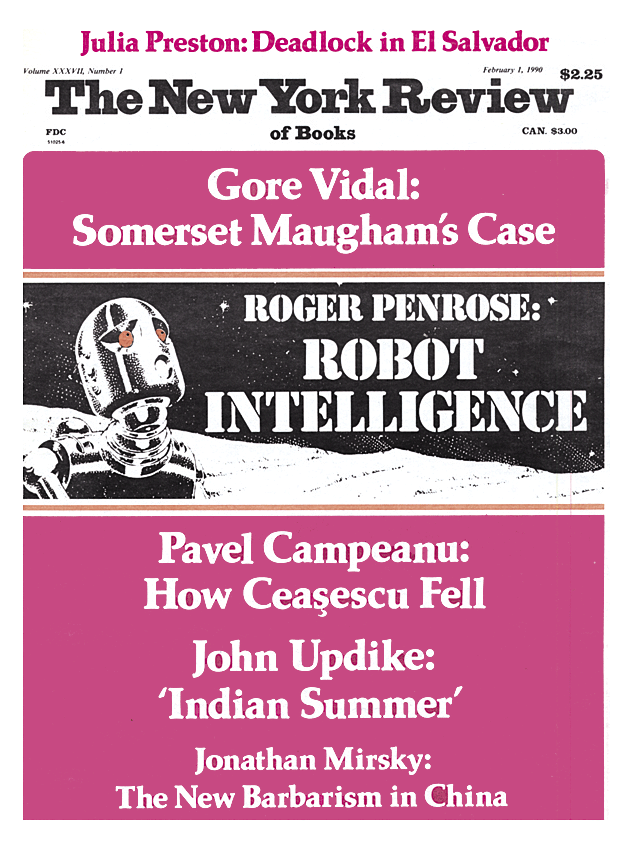

This Issue

February 1, 1990

-

1

Scribner’s, 1977. ↩

-

2

In 1948, after Tennessee Williams had read my “bold” novel, The City and the Pillar, we tried to remember what books we had read that dealt, overtly or covertly, with same-sexuality. Each had a vivid memory of The Narrow Corner. According to Mr. Calder, Maugham himself was somewhat nervous of his romantic indiscretion. “Thank heavens nobody’s seen it,” he said to nephew Robin at about the same time that Tennessee and I were recalling a novel each had intensely “seen.” Another novel that each had read was James M. Cain’s Serenade (1937), where bisexual singer loses voice whenever he indulges in same-sex but gets it back when he commits other-sex, which he does, triumphantly, in Mexico one magical night in the presence of—get cracking Williams scholars—an iguana. ↩