Very winsome are Peter Rabbit, Jemima Puddleduck, Squirrel Nutkin, and other Beatrix Potter creations as they appear on the mugs and porridge plates on sale in National Trust shops. Delightfully quaint were the mice from the Tailor of Gloucester in eighteenth-century costume that last Christmas made the window display at Hamley’s toyshop on Regent Street.

Neither “winsome” nor “quaint” are words to describe the Beatrix Potter who drafted the following letter to a newspaper in 1911 under the heading “Grandmotherly Legislation”:

Under the amended law for the protection of animals it has become illegal for a “child” under 16 years of age to be present at the slaughter and cutting up of carcases. It is unwise to allow little children of 4 or 5 years old to be present at a pig-killing. There have once or twice been serious accidents, where they have tried to imitate the scene in play. But—do our rulers seriously maintain that a farm lad of 15 1/2 years must not assist at the cutting up? One of the interesting reminiscences of my early years is the memory of helping to scrape the smiling countenance of my own grandmother’s deceased pig, with scalding water and the sharp-edged bottom of a brass candle-stick. Pan lids were also in request.

She told the tale of Pigling Bland’s romance with Pig-wig; from her own piglings she sent her friends joints of pork at Christmas. Her liking for animals went far beyond cuddly rabbits and kittens: there are kindly references in her letters to creatures not generally considered lovable: snails, spiders, and rats, whose boldness and ingenuity she admired even as she planned her defenses (“We are putting zinc on the bottoms of the doors—that and cement skirtings will puzzle them”). She considered that her books had succeeded “by being absolutely matter of fact.”

Yet it was not matter-of-factness alone that sent these little books round the world—among the many languages into which they have been translated are Finnish, Icelandic, Bulgarian, Greek, Japanese, and Welsh, and The Tale of Peter Rabbit has been rated the best-selling children’s book of all time in the United States. Beatrix Potter’s down-to-earth realism is laced with fantasy and poetry. Her animals are true to life (she spent hours of her lonely youth drawing her pets) but she delights in the fancy of dressing them appropriately—clogs for the peasant bunnies, print dress for the washerwoman hedgehog, smart green tailcoat for the deceitful fox—and inventing plots to suit their animal nature. And over all she throws a romantic glow that comes from her love of the Lakeland countryside, where nearly all the tales are set.

Now, with the reissue of her Journal (the first edition was reviewed in these pages in 1966) and the publication of the Letters, we are in a better position to understand the author of these far-traveled little books. Judy Taylor introduces the Journal with a tribute to the late Leslie Linder who so passionately devoted himself to deciphering Beatrix Potter’s secret script that “the code had entirely taken over his life.” In her old age Beatrix Potter told a cousin that she had invented the script because she had “an itch to write,” and had been intrigued to learn of Pepys’s private shorthand. It was the resource of a solitary child who never went to school, had no child friends, and lived with remote and unimaginative parents in a gloomy London house without warmth or fun. The code ensured her privacy: she could say what she liked about relations, pictures, books, the news of the day, pet animals, governesses, fungi, flowers, without fear of disapproval or mockery. In her Journal the painfully shy child could talk as much as she liked—to herself.

The Journal starts in 1881, when she was fourteen, and goes up to 1897. The letters, apart from a handful to her father (where the hand may be childish but the signature is a firm “H. B. Potter”) effectively begin in 1892, and go on to her death in 1843. So we can now follow her through her life in her own words and her own pictures, for the text is generously interspersed with her drawings. Many of the picture-letters to children, like the famous one to Noel Moore, where Peter Rabbit made his first appearance, are here in facsimile; there are photographs of people and places, and seventeen color plates, and Judy Taylor has unobtrusively supplied necessary background information. A splendid book, in looks and content.

In the 1890s, letters to the children of her former governess alternate with letters to a retired postman in Perthshire who shared Miss Potter’s interest in fungi. She was expert in agarics and boleti, successfully challenging the pundits at Kew Gardens about hybrid species. After 1901 her correspondence is mainly with the firm of Frederick Warne, which published Peter Rabbit after it had been turned down by several other houses; she had been introduced to Warne by Canon Rawnsley of Keswick, a friend made during the Potter family’s Lake District holidays. From the first, in her letters to the three brothers, Harold, Norman, and Fruing Warne, Miss Potter stood no nonsense. No aspect of the little books that appeared regularly between 1901 and 1913 escaped her scrutiny: color blocks, cloth binding, endpapers, typeface, ink. She was modest about her drawings, but particular about their reproduction; she had some experience of printing and working in lithograph, and knew what she was talking about: “It is useless to do anything in fine pen and ink for half-tone process; it cuts up the line, and there would be the tone all over the paper.” And very particular about her text: “Often the mere position of a word makes all the difference in the balance of a sentence.” When she heard that some children knew her books by heart, she was sure it was because “I took trouble with the words.” She lectured Harold Warne on being

Advertisement

too much afraid of the public for whom I have never cared one tuppeny-button. I am sure that it is that attitude of mind which has enabled me to keep up the series. Most people, after one success, are so cringingly afraid of doing less well that they rub all the edge off their subsequent work.

The publishers seem to have done all they could to meet her criticisms and sometimes imperious demands, and she found in Norman Warne a true friend. In July 1905 he wrote proposing marriage, and she accepted, to the horror of her parents, for he was “in trade” (Mr. Potter’s father had been a calico printer, but he asserted his gentility by not working). Before they could marry, Norman died of pernicious anemia.

Shortly before his death Beatrix had bought a place for herself in the Lake District, between Windermere and Esthwaite, the lake where Wordsworth skated as a boy. Hill Top Farm was in the village of Near Sawrey, “as nearly perfect a little place as I ever lived in.” There she spent all the time that she could get away from her demanding parents—well into her forties she was liable to be sent for whenever they were ill, or when there were “muddles with servants.” After the purchase of the farm the letters—many of them to Norman Warne’s sister Millie—are full of country matters: pigs going to market, sheep sales, visits to the quarry for stone for the flagged path, plans for a “regular old fashioned farm garden, with a box hedge round the flower bed, and moss roses and pansies and black currants and strawberries and peas—and big sage bushes for Jemima.” She complains of a helper who tries to make a genteel tennis lawn when she wants a potato patch. She is delighted when a quarryman gives her some splendid phloxes, and has no shame in pinching plants from an old lady’s overgrown garden: “Mrs. Satterthwaite says stolen plants always grow, I stole some ‘honesty’ yesterday.”

The farmhouse itself was in poor condition—“the first thing I did when I arrived was to go through the back kitchen ceiling”—but in a year or two she had filled it with nice old furniture picked up at local sales, and made it into the house where the Two Bad Mice rampaged and where Samuel Whiskers made Tom Kitten into a roly-poly pudding.

The first success of her books had given her the welcome knowledge that she could earn her own living; now she needed to earn for the farm as well. So she was ready to fall in with Warne’s plans for licensing manufacturers to use her animal characters for dolls, wallpaper, and china: cuddly Peter Rabbits and nursery friezes could pay for more sheep, another field. She prodded the Warnes’ firm—always “sadly behindhand” to pay their royalty cheques more promptly.

In 1913 she married William Heelis, the solicitor in Ambleside who had acted for her in the purchase of Hill Top, and who soon “asserted himself upon the subject of hens and put down Mr. Simpson our new neighbor.” Again her parents disapproved, for a country solicitor was much beneath them, and a few days after the wedding claimed her back because “my mother is changing servants.” Hill Top and marriage turned her life round. Just after Norman Warne died, she confessed that when she’d read his proposal she’d felt, like Anne Elliot in Persuasion, that “my story had come right, with patience and waiting.” Fifteen years after becoming Mrs. Heelis she could say (the letter is not in Judy Taylor’s selection, but can be found in Margaret Lane’s biography* ), “I married very happily…. What are the words in The Tempest? ‘Spring come to you at the farthest, in the very end of harvest.’ ” Willie Heelis was unpunctual, untidy in the house, and dilatory in the office; she acknowledged that she was “the stronger-minded of the pair”; but she loved and cherished him and made excuses when he was slow in repaying what he owed his clients, just as Harold Warne had so often been with her. Though in 1913 nearly all the little books were behind her, the years as Mrs. Heelis can be counted as the most productive as well as the most satisfying of her life.

Advertisement

Their home was Castle Cottage, close to Hill Top, where she had installed a housekeeper to look after the shepherd, dairyman, and ploughman. Her farming was no pastoral hobby. “I have farmed my own land for ten years as a business,” she told a prospective helper in 1916:

I have poultry, orchard, flower garden, vegetables, no glass, help with heavy digging, cooking with the girl’s assistance. Mrs. C., I and this girl all help with hay, and I single turnips when I can find time.

She could be met “sliding down the Kirkstone banks,” or wheeling a barrow with acorns for her pigs, wearing a man’s cap and a sack across her shoulders to keep off the rain. She was delighted when a jolly farmer at the Hawkshead Agricultural Show “likened me—the president—to the first prize cow!”

In 1924 she launched out boldly, buying the two-thousand-acre Troutbeck Park Farm—“plain land” and none the worse for it, high above Windermere toward the Kirkstone Pass—and over one thousand Herdwick sheep, a breed that thrives on the high fells. The farm needed much improvement (“Herdwick men are untidy farmers”): drains and fences, a new range for the farm kitchen. Soon she could say of her flock “I know them and the fell like a shepherd,” and was winning prizes at local shows. “Had the best Herdwick ewe and gained the challenge cup to hold for a year.” As president of the Herdwick Association she had, according to the Penrith Herald, “a wonderful way of making her views crystal clear, whether in speech or writing.” When a champion ram died, she wrote his obituary for a local paper:

Wedgewood was the perfect type of a hard big boned Herdwick up; with strong clean legs, springy fetlocks, broad scope, fine horns, a grand jacket and mane. He had strength without coarseness. A noble animal.

When she bought Troutbeck Farm, she decided to leave it in her will to the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty. Her friend Canon Rawnsley was one of the three founders of the Trust, and its earliest purchases had been in the Lake District. Many of her letters from 1926 onward are on Trust matters. She would alert headquarters in London about properties likely to come on the market, like the little old bridge house at Ambleside—“not beautiful; but it will be looked for, and missed, if it goes down,” or the strip of foreshore near Windermere Ferry threatened by builders. When in 1929 she heard through the Heelis office that the Monk Coniston estate of five thousand acres between Coniston and Little Langdale was to be sold, she proposed to buy the estate herself, on condition that the Trust buy half from her when they could raise the money. “The matter is urgent;…there is a building development creeping up from Skelwith Bridge…. The thing must be done somehow.”

Now, with the prestige of a major benefactor, she kept the Trust and its agents up to scratch, as sharp on backsliding and sloppy work as she had been with the Warnes over the production of her books. “The sanitation is not nice at the Trust’s Tilberthwaite cottages—and as for Stony End—there are 15 people using one earth closet.” She specifies the right kind of wire for fencing—“1 cwt No 9 Hercules woven wire,” “do not be put off with anything thinner than 9″—and where it can be bought. Yet the local agent puts up the wrong kind, “he seems to have no understanding about anything; and he is not learning either.” Nor did he follow her advice about felling timber, and “destroyed the finest group of oaks on Thwaite.” She must have been a holy terror to the poor man; from London the Trust sent him soothing words about “a rather exaggerated outpouring of an injured lady’s mind,” but warned him not to alienate the Heelises.

The Lakeland that she defended so fiercely (“I begin to assert myself at seventy”) was not just a matter of picturesque lakes and mountains and the homes of great poets, but a working landscape of farms and fields and stone walls and fells where sheep grazed—“plain lands” as well as beauty spots. It was a countryside where visitors were welcomed if they respected its proper character and did not charge about the footpaths on motorbikes, or leave bottles on the grass (“I picked up 7 or 8, two were near the Tarns; some glass was almost too hot to handle”), or start fires with their cigarette ends, or fly airplanes low over Windermere: “It makes a noise like ten million bluebottles.” When war threatened, it was a consolation to reflect that “Hitler cannot spoil the fells; the rocks and fern and lakes and waterfalls will outlast us all.” Lying in bed, in her last years, she could still with her “seeing eye”

walk step by step on the fells and rough lands seeing every stone and flower and patch of bog and cotton grass where my old legs will never take me again.

Peter Rabbit and its successors became mainly valued for their contribution to her farming and property transactions. She was increasingly testy in her letters to her publisher about “these d——d little books.” “When one is up to the eyes in work with real live animals it makes one despise paper-book animals,” she told Fruing Warne in 1918 when he urged her to write another book. “It is much easier for me to attend to real live pigs and rabbits; and after all I have done about 30 books, so I have earned a holiday.” Also, her eyes were giving her trouble, and she could no longer see colors so precisely.

The Warnes themselves were in trouble, with Harold Warne sent to prison in 1917 for transferring cash from the publishing business to an ailing family fishing project. Beatrix—their greatest asset and chief creditor—sympathized with Fruing Warne, who had to sell his house (though she bracingly reminded his wife that “there will be less housekeeping in a smaller house”) and readily fell in with his suggestions for further spinoffs from her books—board games, stationery, pocket handkerchiefs.

But no more new books, and above all, no publicity. The pleasant thing about her large sales was that “it has been done quietly and old fashioned like.” All requests for interviews and articles were firmly turned down. “I hate publicity; and I have contrived to survive to be an old woman without it, except in the homely atmosphere of Agricultural Shows.” There, and in village life, she was in her element:

We had a very jolly party last Saturday, commencing with infants at 2.30 and advancing through relays of uproar and refreshments to farm servants and dancing till 11.

Willie had a nimble foot for country dancing. She welcomed the Scouts and Guides who camped in her field at Hill Top (or sheltered in her barn):

It is always a pleasure to help Guides, and it brings its own reward—for surely it is a blessing when old age is coming, to be able still to understand and share the joy of life that is being lived by the young. If I slept in a tent I might get sciatica; I enjoy watching Guides, smiling in the rain.

Local goings-on provided entertainment in plenty. When the Moral Rearmament Movement was active in Hawkshead and recruited Willie’s brother, she commented that “Jack does not seem to come to the office any more punctually; but it is harmless.” Certainly she was not to be won over. “I am not conscious of hating anybody,” she told a Heelis niece, “and your Uncle cannot publicly confess his sins as a solicitor nor other peoples’s.”

Mrs. Heelis was not affronted when the passengers on a touring bus, alerted by the driver to Beatrix Potter’s home, showed “refreshing ignorance” of Peter Rabbit. She kept British admirers at bay, ordering the Warnes never to reveal her address. Very different was her attitude to her American fans, whom she welcomed to Sawrey. “The New Englanders who have drifted over to Hill Top Farm have been singularly sympathetic,” and she showed their children around the rooms they knew so well from Samuel Whiskers and Two Bad Mice. She found these American visitors much better informed about children’s books than the British, and admired the Boston Horn Book:

a splendid publication; the articles and critiques are so alive; and real criticism, speaking out. Here, the review of the new crop of children’s books is either indiscriminate exaggerated praise, or silence.

In 1929 she allowed Alexander McKay of Philadelphia to publish a collection of her early stories and miscellaneous sketches in which she had been “talking to herself.” Though she looked forward to showing The Fairy Caravan to her shepherd and blacksmith (“my most exacting critics…. I do not care tuppence about anybody else’s opinion”), she wouldn’t have it published in England: she might be revealing too much of herself. (It was the success of The Fairy Caravan in America that gave her the financial nerve to buy the Monk Coniston estate.)

I rather shrink from submitting the talkings to be pulled about by a matter of fact English publisher, or obtruded on my notice in the London Daily.

If they were printed in an American journal and looked silly in print and were considered foolishness, I needn’t see them at all.

Tributes from America were acceptable, but there was short shrift for any nearer home. I must now declare an interest—or rather, an embarrassment. Toward the end of the Letters are two addressed to me in 1943, that nearly half a century later can still make me cringe. Here is the context. I spent the war in Penrith, on the edge of the Lake District, where the shops sold wide-woven baskets such as those that imprisoned Peter Rabbit and Benjamin Bunny in Mr. McGregor’s garden, and my four-year-old daughter wore clogs like theirs.

Now a resident in the Lakes, and no longer a mere vacationer, I realized as I read the little books to my children how truly Beatrix Potter’s pictures had caught the enduring character of this countryside. The white farmhouses, the stone walls sprouting ferns and flowers, the slates on the fellside that marked the entrance to old mine workings (or Mrs. Tiggywinkle’s snug home) were there in our lives as well as in the books. I knew little of Beatrix Potter except that she lived somewhere beyond Windermere and had been a friend of my parents’ great friend Canon Rawnsley. I knew nothing of her horror of publicity, or how upset she had been a year or two earlier by Graham Greene’s affectionate and admiring joke, when he wrote of her oeuvre in the way old-fashioned critics once wrote of Shakespeare: the great comedies (Two Bad Mice, Tom Kitten); the “dark” comedies, with their Jamesian hints of treachery (Jemima Puddleduck); the near-tragedy of Mr. Tod. Mrs. Heelis thought she was being mocked. Unaware of such things, I wrote an article for The Listener on my rediscovery of Beatrix Potter, her truthfulness to the life of the Lakes, the romantic glow with which she suffused her landscapes through her particularizing of detail. This put her, I thought, “in the same company” as Samuel Palmer, Calvert, Bewick. The piece was written with enthusiasm and love, and I had many appreciative letters.

But not from Mrs. Heelis. To her I must have seemed an impertinent young woman who was jerking her away from her settled persona as wife, farmer, flockmaster, National Trust watchdog, back into the creator of the little books that now so bored her, and (she thought) putting her up among great painters whom she revered. (I’d only said that the “dewy freshness” found in Constable was there also in her Lakeland scenes, not that she was in Constable’s class!) She was always modest about her paintings, and could not know that many of her watercolors would eventually find a home in the Victoria and Albert Museum along with those of the artists I’d named. When she scolded me for saying that her books were “founded on the work of the Immortals—all names which I revere,” I tried to explain that I’d never said that at all. It was hopeless, and to another correspondent who had sent her The Listener, she gave her verdict: “The article is nicely written and well meant—but surely great rubbish? Absolute bosh.”

Coleridge, who had lived in the Lakes, walked the fells, climbed the crags, and exulted in the waterfalls, lamented the passing of

The fair humanities of old religion,

The Power, the Beauty, and the Majesty,

That had their haunts in dale, or piny mountains

Or forest by slow stream, or pebbly spring,

Or chasms and wat’ry depths; all these have vanished.

They live no longer in the faith of reason!

But still the heart doth need a language, still

Doth the old instinct bring back the old names.

No oreads now on piny mountains, no fauns by pebbly springs! I used to think that Beatrix Potter’s creatures took the place of such familiar spirits—Squirrel Nutkin on Derwentwater, Mrs. Tiggywinkle on Cat Bells. Now I am sure that the true genius loci is that dumpy little figure—clogs on her feet, sack over her shoulders—who is both the Beatrix Potter who created these kindly animal presences and the Mrs. Heelis who toiled and fought and scolded so that her beloved countryside should endure. But do I hear a tart voice from outer space? “Great rubbish! Absolute bosh!”

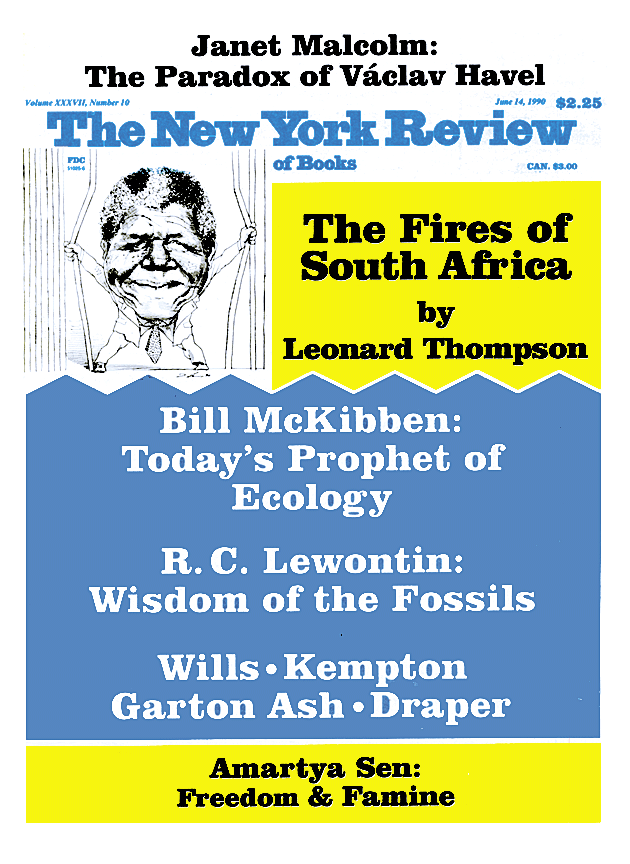

This Issue

June 14, 1990

-

*

Margaret Lane, The Tale of Beatrix Potter (Warne, 1946; Penguin, 1986). ↩