Theodore Seuss Geisel, known to millions as Dr. Seuss, is the most popular living juvenile author in America today. Almost everyone under forty was brought up on his books and cartoons, and even those who didn’t hear the stories read aloud or see them on TV probably met his fantastic characters at school. Beginning with The Cat in the Hat in 1957, Seuss revolutionized the teaching of reading, managing to create innovative, crazily comic tales with a minimum vocabulary (The Cat in the Hat uses only 220 words). The inventive energy of these books and their relative freedom from class and race norms made middle-class suburban Dick and Jane look prissy, prejudiced, and totally outdated.

What made it all the more wonderful was that Dr. Seuss’s life was a classic American success story. He began as a cartoonist and advertising artist; his “Quick, Henry, the Flit!” drawings showing a citizen attacked by giant insects, half-comic and half-threatening, were widely reproduced. But his first children’s book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, was rejected by forty-three publishers; it was finally printed in 1937 only as a favor by a friend.

Why didn’t editors see at once what a winner Seuss would be? Partly because of his artistic style, which was unabashedly cartoon-like and exaggerated in an era when children’s book illustration was supposed to be pretty and realistic. Perhaps even more because of the content of his stories, especially their encouragement of wild invention and, even worse, the suggestion that it might be politic to conceal one’s fantasy life from one’s parents. Children in the Thirties and Forties were supposed to be learning about the real world, not wasting their time on daydreams, and they were encouraged to tell their parents everything.

Marco, the hero of And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, is warned by his father at the start of the book to “stop telling such outlandish tales” about what he sees on the way home from school. Yet the very next day his imagination turns a horse and wagon, by gradual stages, into a full-blown parade with elephants, giraffes, a brass band, and a plane showering colored confetti—all portrayed by Seuss with immense verve and enthusiasm. Marco arrives home in a state of euphoria:

I swung ’round the corner

And dashed through the gate,

I ran up the steps

And I felt simply GREAT!

FOR I HAD A STORY THAT NO ONE COULD BEAT!

Then he is quizzed by his father about what he has seen. His reply is evasive:

“Nothing,” I said, growing red as a beet,

“But a plain horse and wagon on Mulberry Street.”

The message that it is sometimes, perhaps always, best to conceal one’s inner life reappears in The Cat in the Hat. Here “Sally and I,” two children alone and bored on a rainy day, are visited by the eponymous Cat. He proceeds to totally destroy the house, causing first excitement and then panic (What will their mother say?). Finally he puts everything back in place. The kids—and not only those in the story, but those who read it—have vicariously given full rein to their destructive impulses without guilt or consequences. When their mother returns and asks what they’ve been doing, there is a strong suggestion that they might not tell her:

Should we tell her about it?

Now, what SHOULD we do?

Well…

What would YOU do

If your mother asked YOU?

In these tales the children whose imagination transforms the world are abashed or secretive when confronted with possible adult disapproval. More often, however, Seuss lets fancy run free without equivocation or apology. A whole series of books from McElligot’s Pool through On Beyond Zebra! and If I Ran the Circus celebrates the wildest flights of fantasy. They usually begin in familiar surroundings, then move into an invented world where the scenery recalls the exotic landscapes of Krazy Kat comics. There, just as Seuss’s Elephant-Bird, Tufted Gustard, and Spotted Atrocious defy natural history, so his buildings and roads and mountains defy gravity, seeming always to be on the verge of total collapse.

Though these stories are full of euphoric vitality, there is occasionally something uneasy and unsatisfying about them. Seuss’s verbal inventions can become as shaky and overblown as the structures in his drawings. At the end of these books the elaborate language always does collapse. There is an abrupt return to simple diction, and a simple, realistic illustration implicitly declares that Seuss’s protagonist was only fantasizing.

Innovative as he was, Seuss can also be seen as squarely in the tradition of American popular humor. His strenuous and constant energy, his delight in invention and nonsense recall the boasts and exaggerations of the nineteenth-century tall tale, with its reports of strange animals like the Snipe and the Side-Winder. Seuss brought this manner and these materials up to date for a generation raised on film and TV cartoons. And, though most of the time he addresses himself almost exclusively to children, he includes occasional jokes for adults. In If I Ran the Zoo, for instance, the hero plans to bring a Seersucker back alive; he will also “go down to the Wilds of Nantucket / And capture a family of Lunks in a bucket.” According to the illustrations, the Seersucker is a foolish, shaggy, flower-eating animal with what looks like a red bow tie, while Lunks are pale, big-eyed creatures with blond topknots, captured with the help of beach buggies.

Advertisement

Parents as well as children seem to be addressed in One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish (1960), in which two kids find a very large uncomfortable-looking tusked sea monster. They exult:

Look what we found

in the park

in the dark.

We will take him home.

We will call him Clark.He will live at our house.

He will grow and grow.

Will our mother like this?

We don’t know.

But Seuss is not only in favor of the free-ranging imagination; in many of his books there is a strong liberal, even anti-establishment moral. As in the classic folk tale, pride and prejudice are ridiculed, autocratic rule overturned. In Yertle the Turtle, Mack, who is bottom turtle on the live totem pole that elevates King Yertle, objects to the system:

I know, up on top you are seeing great sights,

But down at the bottom we, too, should have rights….

Besides, we need food. We are starving!

So he burps and upsets the whole stack, turning Yertle into King of the Mud. In Bartholomew and the Oobleck another overreaching ruler, dissatisfied with the monotony of the weather, commands his magicians to cause something more interesting than rain or snow to fall from the sky. He gets a sticky, smelly substance which, though it appears as green, is clearly excrement (“You’re sitting in oobleck up to your chin”); it does not disappear until he admits that the whole thing was his own fault.

In Horton Hatches the Egg and Horton Hears a Who) a charitable and self-sacrificing elephant protects the rights of the unborn and of small nations and obscure individuals in spite of the ridicule and scorn of his friends, because “A person’s a person, no matter how small.” There are limits to charity in Seuss, however. Thidwick the Big-Hearted Moose allows his horns to become the refuge of an overwhelming number of immigrant animals and bugs, repeating wearily that “A host, above all, must be nice to his guests.” Luckily, just when he reaches the limits of his endurance and is being pursued by hunters, his antlers moult and he escapes. His guests end up stuffed and mounted on the wall of the Harvard Club, “as they should be.”

For years Seuss’s tales were hailed by experts as a wonderful way to teach children not only reading but moral values. Recently, however, a couple of them have run into opposition. Last year loggers in northern California went after The Lorax (1971). In this story, a greedy Once-ler and his relatives move into an area of natural beauty and proceed to chop down all the colorful Truffula Trees in order to manufacture Thneeds, which resemble unattractive hairy pink underwear. Soon the sky is choked with smog and the water with something called Gluppity-Glup. Though Seuss said the book was about conservation in general, the loggers saw it as blatant propaganda and agitated to have it banned from the school’s required reading list. “Our kids are being brainwashed. We’ve got to stop this crap right now!” shouted their ad in the local paper, taking much the same belligerent anti-environmentalist tone as the Onceler himself does when criticized:

I yelled at the Lorax, “Now listen here, Dad!

All you do is yap-yap and say ‘Bad! Bad! Bad! Bad!’

Well, I have my rights sir, and I’m telling you

I intend to go on doing just what I do!

And for your information, you Lorax, I’m figgering on biggering and BIGGERING

and BIGGERING

and BIGGERING

turning MORE Truffula Trees into Thneeds

which everyone, EVERYONE, EVERYONE needs!”

The Butter Battle Book (1984), a fable about the arms race, also provoked unfavorable comment. Like Swift’s tale of the Big- and Little-Endians who went to war over how to open an egg, it begins with a meaningless difference in domestic habits. Two groups of awkward-looking flightless birds, the Yooks and the Zooks, live side by side; the Yooks eat their bread butter side up, the Zooks prefer it butter side down. They become more and more suspicious of each other, and finally a member of the Zook Border Patrol with the rather Slavic-sounding name of Vanltch fires his slingshot. Escalation begins: more and more complicated weapons are developed by the Boys in the Back Room (“TOP-EST, SECRET-EST, BRAIN NEST” says the sign on their door), until both sides possess the means of total destruction. Unlike most of Seuss’s books, this one doesn’t end reassuringly, but with the child narrator asking anxiously, “Who’s going to drop it? / Will you… ? Or will he… ?” The New York Times Book Review considered the story “too close to contemporary international reality for comfort,” while The New Republic, somewhat missing the point, complained that the issues between our real-life Zooks and Yooks were more important than methods of buttering bread.

Advertisement

Other, perhaps more relevant criticisms might be made today of Seuss’s work. For one thing, there is the almost total lack of female protagonists; indeed, many of his stories have no female characters at all. The recent You’re Only Old Once!, a cheerfully rueful tale about the medical woes of a senior citizen, which was on the best-seller list for months, is no exception. It contains one female receptionist (only her arm is visible) and one female nurse, plus a male patient, a male orderly, and twenty-one male doctors and technicians. There is also one male fish.

The typical Seuss hero is a small boy or a male animal; when little girls appear they play silent, secondary roles. The most memorable female in his entire oeuvre is the despicable Mayzie, the lazy bird who callously traps Horton into sitting on her egg so that she can fly off to Palm Beach. Another unattractive bird, Gertrude McFuzz in Yertle the Turtle and Other Stories, is vain, envious, greedy, stupid, and fashion-mad. She gorges on magic berries to increase the size of her tail, and ends up unable to walk.

Seuss’s little girls, unlike his boys, are not encouraged to exercise and expand their imagination very far. In “The Gunk that Got Thunk,” one of the tales in I Can Lick 30 Tigers Today!, this is made clear. The narrator relates how his little sister customarily used her “Thinker-Upper” to “think up friendly little things / With smiles and fuzzy fur.” One day, however, she gets bored; she speeds up the process and creates a giant Gunk:

He was greenish.

Not too cleanish.

And he sort of had bad breath.

She tries to unthink him, but fails; meanwhile the Gunk gets on the phone and runs up a $300 long-distance bill describing recipes. Finally he is unthunk with the help of the narrator, who then gives his sister

Quite a talking to

About her Thinker-Upper.NOW…

She only

Thinks up fuzzy things

In the evening after supper.

Moral: Woman have weak minds; they must not be ambitious even in imagination.

Seuss’s most recent book, which has been on the New York Times best-seller list for thirty-nine weeks, also has a male protagonist. But in other ways Oh, the Places You’ll Go! is a departure for him. “The theme is limitless horizons and hope,” Seuss, now eighty-six years old, told an interviewer, and the blurb describes the book as a “joyous ode to personal fulfilment”; but what it really reads like is the yuppie dream—or nightmare—of 1990 in cartoon form.

At the beginning of the story the standard Seuss boy hero appears in what looks like a large clean modern city (featureless yellow buildings, wide streets, tidy plots of grass). But under this city, as an urbanite might expect, are unpleasant, dangerous things—in this case, long-necked green monsters who put their heads out of manholes. Seeing them, Seuss’s hero, “too smart to go down any not-so-good street,” heads “straight out of town.”

At first everything goes well; he acquires an escort of four purple (Republican?) elephants, and rises in the world, joining “the high fliers / who soar to high heights.” The narrative is encouraging:

You’ll pass the whole gang and you’ll soon take the lead.

Wherever you fly, you’ll be best of the best.

Wherever you go, you will top all the rest.

In the accompanying illustration Seuss’s hero is carried by a pink and yellow balloon high over fields and mountains; his competitors, in less colorful balloons, lag behind at a lower altitude.

Then comes the first disaster: the balloon is snagged by a dead tree and deflated. The boy’s “gang” doesn’t stop for him—as presumably he wouldn’t for them—and he finds himself first in a Lurch and then in a Slump, portrayed as a dismal rocky semi-nighttime landscape with giant blue slugs draped about. Doggedly, he goes on and comes to a city full of arches and domes which looks rather Near Eastern,

where the streets are not marked.

Some windows are lighted. But mostly they’re darked.

Turning aside (in the light of recent events, an excellent choice), he continues “down long wiggled roads” toward what Seuss calls The Waiting Place. Here the sky is inky black and many discouraged-looking people and creatures are standing about:

…waiting, perhaps, for their Uncle Jake

or a pot to boil, or a Better Break.

For the energetic, ever-striving young American, this is a fate worse than death, and it is vigorously rejected:

NO!

That’s not for you!Somehow you’ll escape

all that waiting and staying.

You’ll find the bright places

where Boom Bands are playing.

Seuss’s hero is next seen riding another purple elephant in a procession of elephants, on his way to further solitary triumphs.

Oh, the places you’ll go. There is fun to be done!

There are points to be scored. There are games to be won….

Fame! You’ll be famous as famous can be,

with the whole wide world watching you win on TV.

In the accompanying picture, some kind of fantasy football or lacrosse is being played—our hero kicking off from the back of his elephant, the other contestants on foot. But almost immediately this success is undercut:

Except when they don’t

Because, sometimes, they won’t.I’m afraid that some times

you’ll play lonely games too.

Games you can’t win

’cause you’ll play against you.

The most dangerous enemy of the celebrity is his own doubt and self-hatred. The illustration shows a totally insecure-looking fantasy version of a Hollywood hillside mansion, where the protagonist is shooting baskets alone. Seuss assumes, no doubt quite properly, that in any career devoted to success, competition, and fame, “Alone will be something / you’ll be quite a lot,” and that often “you won’t want to go on.”

But his hero, of course, does go on, meeting a number of comical and/or frightening monsters.

You’ll get mixed up

with many strange birds as you go…

Seuss predicts. The strange birds, who all look alike, are shown against another totally black background, some marching upward to the right with smiles, others plodding downward to the left with depressed expressions. The message here seems to be that it is a mistake to commit oneself to any organization; instead one must

Step with care and great tact

and remember that Life’s

a Great Balancing Act.

This is followed by the happy climax, in which Seuss’s hero is even more triumphant than before:

And will you succeed?

Yes? You will, indeed!

(98 and 3/4 percent guaranteed.)KID, YOU’LL MOVE MOUNTAINS!

This promise is depicted literally in the illustration; if we chose to take it that way; we might assume that Seuss’s “kid” has become a property developer, like so many California celebrities.

In one or two of Seuss’s earlier books, similar dreams of money and fame occur. Gerald McGrew, for instance, imagines that

The whole world will say, “Young McGrew’s made his mark.

He’s built a zoo better than Noah’s whole Ark!…“WOW!” They’ll all cheer,

“What this zoo must be worth!”

(If I Ran the Zoo)

This was written in 1950, when Seuss’s own imaginary zoo had just begun to make his fortune. Today life has wholly imitated art; his wild inventions, like those of his boy heroes—and of course in the end they are the same thing—have made him fantastically rich and famous. It is difficult to estimate what Seuss’s own zoo must be worth now: according to his publishers, over 200 million copies of his forty-two books have been sold worldwide, and many have been animated for TV.

Gerald McGrew and Seuss’s other early heroes were content simply to fantasize success. Oh, the Places You’ll Go! has a different moral. Now happiness no longer lies in exercising one’s imagination, achieving independence from tyrants, or helping weaker creatures as Horton does. It is equated with wealth, fame, and getting ahead of others. Moreover, anything less than absolute success is seen as failure—a well-known American delusion, and a very destructive one. There are also no human relationships except that of competition—unlike most of Seuss’s earlier protagonists, the hero has no friends and no family.

Who is buying this book, and why? My guess is that its typical purchaser—or recipient—is aged thirty-something, has a highly paid, publicly visible job, and feels insecure because of the way things are going in the world. It is a pep talk, and meets the same need that is satisfied by those stiffly smiling economic analysts who declare on television that the present recession is a Gunk that will soon be unthunk, to be followed—On Beyond Zebra!—by even greater prosperity.

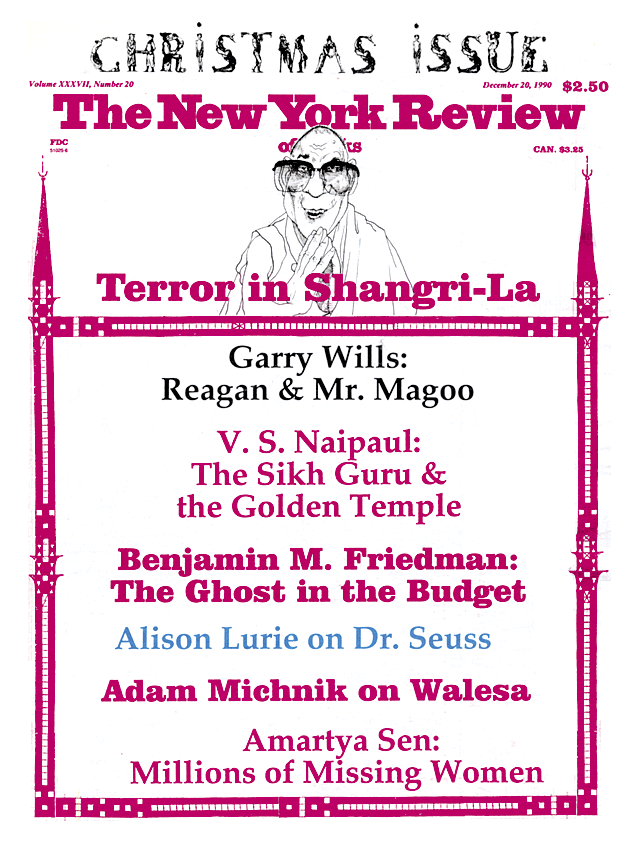

This Issue

December 20, 1990