Note: Of the following poems by Kocbek, the first reflects his experiences as a Partisan leader. The second and third reflect his disillusionment with communism. The fourth poem could be read as an account of the entire Slovene nation today as it fights for its independence.—MS

HANDS

I have lived between my two hands

as between two brigands,

neither knew

what the other did.

The left hand was foolish because of

its heart,

the right hand was clever because of

its skill,

one took, the other lost,

they hid from one another

and only half-finished everything.

Today as I ran from death

and fell and rose and fell

and crawled among thorns and

rocks

my hands were equally bloody.

I spread them like the cruciform

branches

of the great temple candlestick,

that bear witness with equal ardor.

Faith and unfaith burned with a single

flame,

ascending hotly on high.

PARROTS

Termites attacked the province

undermined bridges and monuments,

tables and beds all crumbled to

dust.

Germs infiltrated laboratories

and settled on the sterilized

instruments,

fooling learned men in the process.

It all happened so horribly quietly.

In our case it was a plague of parrots.

Green and yellow, they screeched

in our houses, gardens and kitchens;

unclean, vulgar and ravenous

they invaded our bathrooms and

bedrooms

and finally settled in people.

It all happened so horribly loudly.

None of us knows how to lie any more

and none can tell the truth;

we speak the tongue of an unknown

tribe,

we yell and curse and howl and wail,

draw back our lips and pop out our eyes;

even the court jester has gone insane

and is screeching like all the rest.

Somewhere, though, stands a circle of

men

gazing mutely at the still center;

motionless they stand in blessed silence,

their shoulders growing broader and

broader

under their ancient burden of silence.

When they suddenly turn about face

the parrots in us will die.

NOW

When I spoke

they said I was dumb,

when I wrote

they said I was blind,

when I walked away

they said I was lame.

And when they called me back

they found I was deaf.

They confounded all my senses

and concluded I was crazy.

This pleases me.

ON FREEDOM OF MIND

I want no more fine phrases,

only one word is left for me,

when I fall on the couch I say: no,

and when I dream I cry suddenly: no,

and when I wake I say again: no.

That is my form of defiance,

it makes me healthy and stubborn.

Even when I am tired

I can still say the word: no,

and when everyone is saying; yes,

I bellow that little word: no.

With this word I control the

situation,

it’s my form of self-affirmation,

it makes me clear-headed and

cruel.

I am kin to the roots and tendrils,

to ruthless tempests and breezes;

computer printouts are shredded

by my brief: no.

The calculation has to begin again.

When they say I am guilty

my actions say I am innocent.

The law of freedom of the human mind

is like the quiet defense of ancient rights,

a command to the clown is a

prohibition,

I don’t want to be a madman or monster,

I grow hoarse amid the din of machines,

from mountain to mountain—nine

echoes of: no;

my neighbor hears it as: yes.

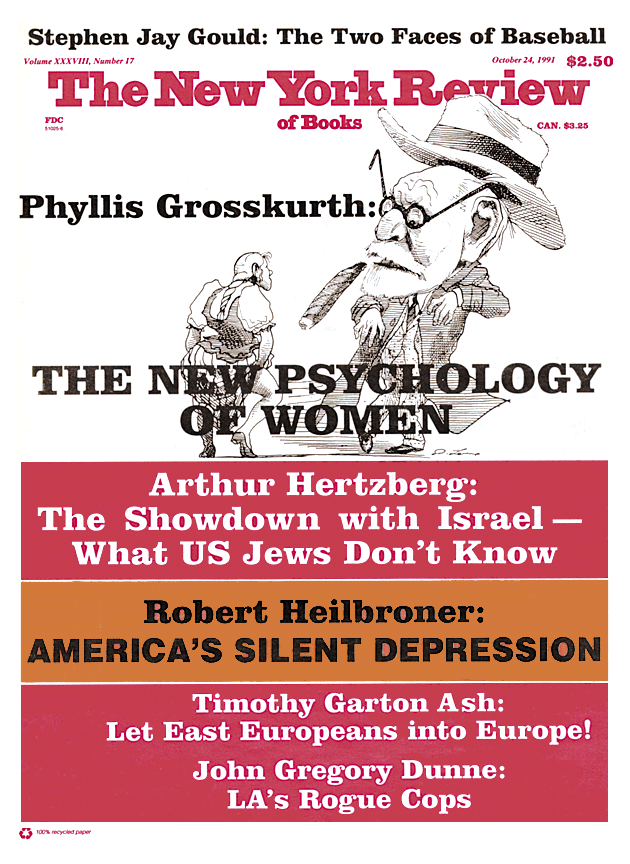

This Issue

October 24, 1991