“In the name of God amen I William Shakespeare of Stratford upon Avon in the county of War-wick gentleman in perfect health and memory God be praised do make and ordain this my last will and testament in manner and form following. That is to say first I commend my soul into the hands of God my creator, hoping and assuredly believing through the only merits of Jesus Christ my Saviour to be made partaker of life everlasting, and my body to the earth whereof it is made.”

With these words Shakespeare began his will, shortly before his death in 1616, bequeathing to the world a statement of his assets and naming several of his closest friends. The will appears to adopt the impersonal jargon of lawyers and thus, despite the famous “second-best bed,” to conceal rather than reveal the testator. I want to compare the will with others of the same period and to suggest that Shakespeare’s failure to observe some testamentary conventions makes his a most unusual document, one that gives us unexpected insights into his personality and even into his relationship with his wife, Anne Hathaway.

Placing Shakespeare’s will in the cultural traditions of its period, we must compare it not only with London and Stratford wills but, more specifically, with those made by testators belonging to the same social class. After the preamble of a gentleman’s will there were often directions for the funeral. John Heminges, the dramatist’s colleague for at least twenty-two years, said, “And my body I commit to the earth to be buried in Christian manner in the parish church of Mary Aldermanbury in London,” and he requested that “my funeral may be indecent and comely manner performed in the evening, without any vain pomp or cost.” Shakespeare commended his soul to God, “and my body to the earth whereof it is made.”

In itself this abruptness might have little significance—yet it needs to be seen in a larger context. A gentleman at this time would often leave a sum for the repair of his parish church, another sum for a funeral sermon or an annual sermon, and now and then for a monument—not for all but for some of these…let us call them social obligations. Shakespeare’s colleague Thomas Pope left directions in 1603 for his funeral in the parish church and “towards the setting up of some monument on me in the said church and my funeral £20.” Another colleague, Augustine Phillips, asked in 1605 to be buried in the chancel of the parish church and gave “to the preacher which shall preach at my funeral…twenty shillings.”

Shakespeare left no such bequests and this may indicate a lack of interest, or even disaffection. The haste with which his will was prepared cannot be wholly blamed for such omissions since he found time to add other small bequests, which were interlined. Moreover, he did give a generous sum to the poor of Stratford: “Item, I give and bequeath unto the poor of Stratford aforesaid ten pounds.” Some testators asked their churchwardens to distribute such alms. Shakespeare didn’t—is that significant? He remembered only one godchild in his will—is that significant?

Taken singly these points attract no attention; taken together they are a puzzle. Compare John Combe of Old Stratford, gentleman, who directed in 1612, “Item, I give and bequeath to every one of my godchildren before not named five shillings apiece.” Combe also asked to be buried in the parish church, left £60 for a tomb, and twenty shillings a year forever “to make a sermon twice a year”—evidently a more committed son of the church than W. Shakespeare.1

Before I try to explain other curious omissions it will be helpful to remind you of the story of Judith Shakespeare’s marriage and its effect on her father’s will. E.K. Chambers, though he did not know all the facts, guessed correctly, and I follow his narrative. Shakespeare probably first gave instructions for a will in January 1616; a draft was prepared by his lawyer, Francis Collins, consisting of three sheets. On March 25 Shakespeare decided to change his will—“The changes he desired in the opening provisions were so substantial that it was thought best to prepare a new sheet I.” Sheets two and three “were allowed to stand, with some alterations; and in this form it was signed on each sheet by Shakespeare.” Sheet one is “mainly occupied with bequests to Shakespeare’s daughter Judith,” so “it is reasonable to suppose that it was her marriage on 10 Feb. 1616, which determined the principal changes.”2 A lack of confidence in Thomas Quiney, Judith’s husband, could explain these changes, thought Chambers—and a later discovery proved him to be correct.

Others3 have shown that Shakespeare had cause to mistrust his new son-in-law, for Thomas Quiney was forced to appear in open court in the parish church and confess to “carnal copulation” with one Margaret Wheeler. That was to be on March 26; one day earlier, on the 25th, Shakespeare sent for Collins and had his will redrafted to protect his daughter—in effect to ensure that Quiney received none of his money, except under stringent conditions.

Advertisement

Other wills survive in which a member of the family is sharply rapped on the knuckles, most often a son-in-law, as in Shakespeare’s case. Elizabeth Condell, the widow of Shakespeare’s colleague, said of one bequest, “Yet so I do intend the same as that my said son-in-law Mr. Herbert Finch shall never have possession of the same; and therefore my will is that my said executors shall keep those goods in their hands for the good of my…grandchildren…unless my said son-in-law…shall first give good security.” Jacob Meade, who had an interest in the Hope theater, asked his executors to retain a sum for his daughter,

the principal to remain unto and for the only use and behoof of my said daughter, so long as it shall please almighty God that she shall live with her husband Michael Pyttes, whom I will shall have nothing to do or meddle therewith.

Shakespeare’s unloved son-in-law was put in his place even more humiliatingly. He was not mentioned by name, his very existence was not acknowledged, even though the most carefully hedged clauses of the will were clearly devised in response to his unwelcome arrival in the bosom of the family. The thought is not unlike that of Elizabeth Condell and Jacob Meade, but notice the curious phrasing. Daughter Judith was to have £150, and another £150 after three years

if she or any issue of her body be living at the end of three years…. Provided that if such husband as she shall at the end of the said three years be married unto or attain after do sufficiently assure unto her…lands answerable to the portion by this my will given…then my will is that the said £150 shall be paid to such husband as shall make such assurance to his own use.

Such husband? Who could be responsible for this phrasing, just six weeks after Judith Shakespeare married her first husband, Thomas Quiney?

The treatment of Quiney resembles that of another member of the family by marriage—William Hart, the husband of Shakespeare’s only surviving sibling, his sister Joan Hart. I think that it’s fair to say that Joan Hart’s future prospects worried her brother, almost as much as Judith Quiney’s. Her husband was an obscure hatter and, it seems, a poor relation, for Shakespeare left his sister a life tenancy of his house in Henley Street “wherein she dwelleth,” for the peppercorn rent of one shilling a year, and also £20, “all my wearing apparel,” and £5 to each of her three sons. William Hart died a few days before Shakespeare, in mid-April, a fact which could not have been known when Shakespeare revised his will three weeks earlier—therefore the absence of any reference to Hart seems odd, the more so since his sons were too young to wear their uncle’s apparel. But—we must not overlook an indirect reference to Hart. A provisional bequest to Joan Hart of £50, should Judith Quiney not live for three years, was to remain in the hands of Shakespeare’s executors, who were to pay interest to Joan, “and after her decease the said £50 shall remain amongst the children of my said sister”—in other words, was not to go to her husband. The various bequests to the four other members of Hart’s immediate family imply that Shakespeare neither loved nor trusted his brother-in-law.

Elizabeth Condell and Jacob Meade named the sons-in-law who had displeased them. Shakespeare’s will carefully avoids naming Thomas Quiney and William Hart—and names omitted, for one reason or another, seem to me a peculiarity of his will as a whole. Bequests to several friends were interlined, therefore were afterthoughts: for instance, those to Hamnet Sadler, William Reynolds, and to “my fellows John Heminges, Richard Burbage and Henry Condell.” More astonishingly, there was not a single reference to the testator’s wife in the will as first completed. Had it occurred to Shakespeare before the draft was completed that he ought to remember his friends and his wife, he could have added more clauses at a later point in the will: instead they were inserted awkwardly, and none too legibly, in between lines that were already written.

I shall return to Anne Hathaway in a moment. First, though, some other “omissions” from the will. Shakespeare, the owner of one of the largest houses in Stratford, must have kept servants. A gentleman usually remembered his servants in his will—individual bequests to some, and very often a year’s wages for all the rest. “Item, I give…unto those my servants whose names are expressed and declared in the schedule to this my will…the several sums to their names written,” said William Combe of Warwick. Shakespeare left nothing to his servants. Leading actors left bequests to each other and also, in some cases, to the hired men of the company and to their apprentices; Shakespeare left bequests to just three “fellows,” as an afterthought, a smaller number than one might have expected, and nothing at all to hired men or former apprentices, after at least twenty-two years with, basically, the same company.

Advertisement

Another fairly common practice at this time was to forgive all debts in one’s will, or at least small debts, or the debts of impecunious friends or relations. John Combe of Old Stratford, the “noted usurer” who bequeathed £5 “to Master William Shakespeare,” had his own way of forgiving debts—fractionally forgiving them, perhaps inspired by professional instinct. “Item, I give and bequeath to every one of my good and just debtors for every twenty pound that any man oweth me twenty shillings.” Shakespeare, who may have been a money-lender and certainly took others to law to recover debts, forgave no debts in his will.

Compared with other testators from the same social class it may appear that William Shakespeare was totally self-centered and shockingly tight-fisted. Before we jump to conclusions I want to mention another omission, for which I blame not the testator but his lawyer. A wise lawyer made sure that the will he helped to prepare would stand scrutiny in a court of law. If there were deletions in a will it was prudent to certify their authenticity, as on the verso of Samuel Rowley’s will (1624): “Memorandum that these words, ‘and said lease in Plough Alley,’ interlined between the eleven and twelfth lines within written, were interlined before the ensealing and delivery hereof”—with the names of four witnesses. Any insertion or deletion in a will could cause trouble. No one took the precaution of authenticating all the changes in Shakespeare’s will, a more heavily revised will than any I have seen. More extraordinary still, the date at the beginning was interlined above an almost illegible deletion, without being validated by witnesses, although a changed date could have become a vital issue had the will been contested.

I think that we are driven to two conclusions, one old and one new. The old one is that the testator was a very sick man, thought to be on his death-bed—hence the messiness of the will, only one page of which was rewritten (a most unusual procedure); hence the fact that his seal could not be found. (The will ends, “In witness whereof I have hereunto put my seal,” then “seal” was crossed out and “hand” substituted.) In short, the will was a draft, from which a fair copy was to have been made, had there been time—and, just in case time might run out, the testator and five witnesses there and then added their signatures. We happen to know that Shakespeare lived another month: I assume that after March 25 he was in no condition to sign his name again, and that this was the reason why the draft had to serve as his “original will,” the definitive document.

My second conclusion, in which I depart from Chambers and other authorities, is that I see all the unusual features of the will as evidence that the testator himself, and not his lawyer, was largely responsible for its wording and structure. (But compare B. Roland Lewis, The Shakespeare Documents4 : Shakespeare’s will, “more than any other one thing epitomizes the spirit of the man and mirrors his personality.” We differ, however, in approach and about “the spirit of the man.”) One suspects that it was the shock of hearing the news about Thomas Quiney and his misdemeanors that triggered off the rewriting of the will—and, quite possibly, Shakespeare’s final illness as well. The testator’s first priority on March 25 was to sort out his financial relationship with his new son-in-law—nothing else mattered so much to him. He was not in a forgiving mood, and he may have been too ill for his advisers to wish to nudge him to do whatever else was customary—for the church, for his servants, for debtors, and for other unremembered friends.

Now—back to Anne Hathaway. “Item, I give unto my wife my second-best bed with the furniture”—interlined, evidently an afterthought. Beds figure more prominently in wills of the period than any other kinds of furniture, so there is no need for raised eyebrows. Nor is it significant that she was not called “my loving” or “my beloved” wife, as wives normally were, rightly or wrongly. Unlike most other testators, Shakespeare did not use terms of endearment anywhere in his will. Yet neither did his lawyer, Francis Collins, who signed his own will just a year later, in 1617. Legally speaking it scarcely mattered what you called your wife—though, incidentally, it was most unusual not to refer to her by name. One would have expected “Item. I give unto my wife, Anne, my second-best bed….” The only similar case that I remember, of a wife not named, occurs in the will of the actor Alexander Cooke (1614), which was also unusual in one other respect. It begins, “In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, I, Alexander Cooke, sick of body but in perfect mind, do with mine own hand write my last will and testament….” Wills written by the testator himself are rare, and, as in the case of Alexander Cooke, are likely to depart from some of the customary forms and phrases. Others have recently suggested that Shakespeare penned his own will: I don’t agree, yet, as I have said, the thinking and some of the actual words of the will often seem to be the testator’s own, not the time-honored rigmaroles of scriveners and lawyers.

Did Shakespeare, perhaps aware that he was on his deathbed, intend a snub to his wife when he left her the second-best bed? Some have argued that it was a gesture of affection: it would be the marital bed, whereas the best bed would be kept in the best room, reserved for important visitors. Another probable reference to Anne Hathaway persuades me, however, that the wife who was given only a bed, and no jewels or other keepsakes, was not as great a comfort to her husband as he may have wished. On sheet two, the will initially said, “Item, I give, will, bequeath and devise unto my daughter Susanna Hall all that capital messuage or tenement with the appurtenances called the New Place wherein I now dwell,…” etc. At some stage this was changed to “I give…unto my daughter Susanna Hall [and then, interlined] for better enabling of her to perform this my will and towards the performance thereof…”—a puzzling insertion.

What can it mean? New Place and the other properties were going to Susanna in any case. The words “for better enabling of her to perform this my will and towards the performance thereof” seem to imply that the “performance” might be hindered. How, by whom, for what reason? I can think of one person who might have had different thoughts about the disposal of Shakespeare’s “plate, jewels and household stuff,” as they are lumped together and collectively bequeathed in the will—a person who would continue to reside at New Place and who might indeed have hindered the “performance.” If I am right, this oblique allusion to Mistress Shakespeare, who is not named, resembles the treatment of Thomas Quiney and William Hart. Shakespeare meant, I take it, that his daughter Susanna and no one else was to be the mistress of New Place.

What, then, were the provisions made for his widow? If we compare the will of Francis Collins, Shakespeare’s lawyer, it would seem that he treated his wife more generously. Collin’s widow was to be the mistress of the family home for the duration of her life, or until she married again. She was to share “half the residue of my goods” with the eldest son, the other half going to the younger children. She was to be a co-executor, with her eldest son. Shakespeare made his daughter and her husband his executors, not his wife, and his other arrangements were different as well. It is sometimes said that “at common law a widow was entitled to a life estate in one third of any and all those lands in which her husband had held an inheritable interest.” Lawyers warn us, though, that “doubtless some widows were compelled by circumstance or consideration of relationship to accept other or lesser provision.’5 In Collins’s will the life estate in one third of the husband’s heritable interest is spelled out—not in Shakespeare’s, where all lands and leases seem to go directly to Susanna and her husband.

Shakespeare’s relationship with his wife, a major factor in the structure of the will, is not as invisible to us as is often suggested. Is it not significant that John and Mary Shakespeare, the poet’s parents, produced children over a span of twenty-two years (with christenings from 1558 to 1580), whereas William Shakespeare and his wife stopped producing children after only three years of marriage? Though not infertile, they stopped when he was twenty-one and she twenty-nine or thereabouts—unusual before the introduction of modern birth control. Biographers are now pretty well agreed that the poet’s relationship with the dark lady of the Sonnets cannot be waved away as just a literary exercise; if they are right, this too is part of the story of his marriage. And is it not significant, again, that we find not a single reference in the will to any member of Anne Hathaway’s family, apart from the terse mention of Anne herself?

When Shakespeare bought the Blackfriars Gate-House in 1613, three co-purchasers or trustees were named with him in the indenture, though he was to be the sole owner. What was the reason for this legal fiction? Legal experts explain that “the use of trustees had the effect of barring Shakespeare’s widow from any right to the property.”6 This effect was no doubt intended, and it reinforces the impression given by the will.

Wills were by no means as stereotyped as we are sometimes led to believe, and Shakespeare’s must be one of the most truly original of original wills. There are many signs in it of anger or disappointment, obliquely liquely expressed. Apart from Thomas Quiney and William Hart, let us not forget Master Richard Tyler the elder, who was to have received 26s. 8d. “to buy him a ring” in the first version of the will and whose name was simply struck out, though he was still alive.7 Perhaps Shakespeare gave nothing to the church because the church had very recently excommunicated his daughter Judith and her husband and was about to humiliate them again. They may have deserved it, yet it would not be too surprising if Judith’s father resented this public chastisement of his family. Many details appear to fit into a larger pattern; the treatment of Anne Hathaway may be a part of it. It is not a pretty spectacle, the deathbed scene that I have sketched, with an afflicted testator apparently so unforgiving. We can only hope, though not too confidently, that the dead hand, as George Eliot was to call it, does not point accusingly at Anne Hathaway, as well as so many others.

I have strayed from the cultural traditions of the last will and testament to the deathbed scene, about which, again, we can only speculate. Am I correct in thinking that Shakespeare broke most of the rules? If not, readers will soon tell me. It is reassuring, at any rate, that in the only other record that equals Shakespeare’s will in importance as a personal document he also went his own way and made up his own rules: I mean in the account he gave of himself in the Sonnets. In the will and the Sonnets he emerges as unconventional, and highly critical of those closest to him—the young man, the dark lady, and members of his own family. The traditional image of “friendly Shakespeare,” “easy Shakespeare,” “gentle Shakespeare,” presents him as he struck others when in congenial company; the will, like the Sonnets, gives us glimpses of the solitary inner man, and helps—a little—to explain the sustained rage of a Hamlet or a Prospero.8

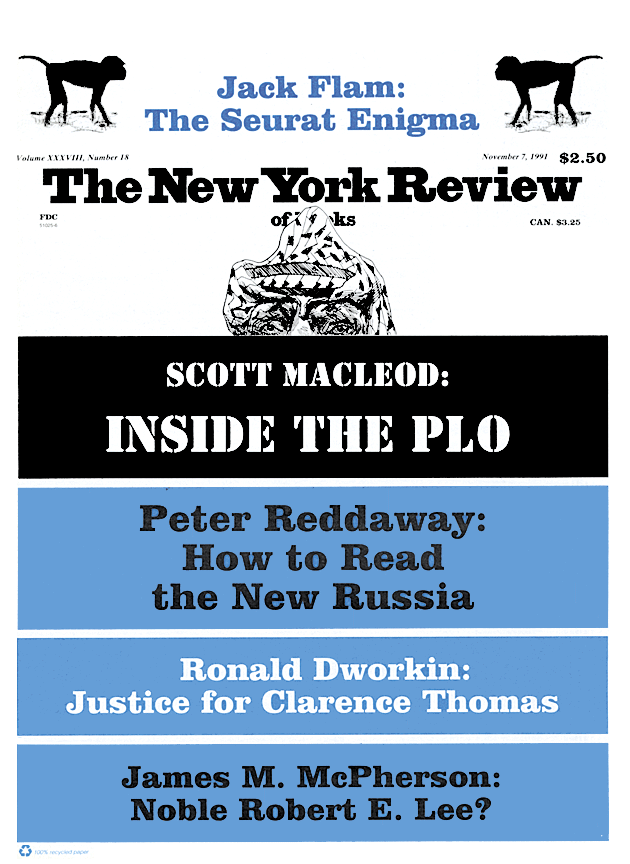

This Issue

November 7, 1991

-

1

I return to Shakespeare’s relationship with his parish church on page 30. It should be added that though he may have acquired the right to be buried in the parish church when he purchased his sublease of Stratford tithes (1605), the significant fact remains that in his will he never alludes to the church or its officers or procedures, and he may well have felt that he had a legitimate grievance (cf. page 30). Again, we should not overlook Richard Davies (archdeacon of Coventry, not far from Stratford), who recorded that Shakespeare “died a papist.” Davies probably wrote his notes on Shakespeare in the later seventeenth century, and is not a reliable witness. On the other hand, Shakespeare’s parents must have married in a Catholic church, in the reign of Queen Mary, and he may have been brought up as a Catholic. ↩

-

2

E.K. Chambers, William Shakespeare, two volumes (Oxford University Press/Clarendon Press, 1930), Vol. II,p. 175 ff. ↩

-

3

See, for example, E.R.C. Brinkworth, Shakespeare and the Bawdy Court of Stratford (Phillimore, 1972), p. 80. ↩

-

4

Two volumes (Stanford University Press, 1940), Vol. II, p. 471. ↩

-

5

Andrew Lewis in The Times Literary Supplement (February 15, 1991), p. 11. ↩

-

6

See The Reader’s Encyclopedia of Shakespeare, edited by O.J. Campbell and E.G. Quinn (Thomas Y. Crowell, 1966), p. 72; also S. Schoenbaum, William Shakespeare Records and Images (Oxford University Press, 1981), p. 43. ↩

-

7

I have modernized the quotations from wills. All the wills except one are in the Public Record Office (Pre-rogative Court of Canterbury), as follows, in alphabetical order: Francis Collins 1617, Prob. 10/347; John Combe 1612, Prob. 10/325; William Combe 1610, Prob. 10/283; Elizabeth Condell 1635 (register copy, 13 Pile); Alexander Cooke 1614, Prob. 10/311; John Heminges 1630, Prob. 10/484; Jacob Meade 1624, Prob. 10/412; Augustine Phillips 1605, Prob. 10/232; Thomas Pope 1603, Prob. 10/224; William Shakespeare 1616, Prob. 1/4. The exception is Samuel Rowley 1624 (Guildhall Library MS. 9172/34). I am grateful for permission to quote extracts from these wills. ↩

-

8

This is a slightly altered version of a paper written for the Fifth World Shakespeare Congress (Tokyo, August 11–17, 1991). In it I draw on a collection of wills by men and women of the “Elizabethan” theater which I am preparing jointly with Dr. Susan Brock of the Shakespeare Institute, University of Birmingham. ↩