1.

Max Weber, born in 1864 as the child of a well-to-do Berlin family, began his scholarly career at the end of the 1880s. It was a time of crisis and turbulence in European thought. The great age of liberalism was coming to an end with the rise of mass politics and new kinds of leaders, popular tribunes with charisma (to use a Weberian term) like Georg von Schönerer and Karl Luager and other precursors of Mussolini and Hitler. Among intellectuals, there was a widespread repudiation of the former faith in historical progress, as well as a tendency to turn away from liberal rationalism to neoromantic forms of philosophical and artistic expression. Characteristic of the crisis, above all, was a deep cultural pessimism, a sense of being trapped in a world of degeneration and decline, of disenchantment with old ideals and a frenetic search for new forms of self-realization—free love movements and youth cults, nature worship and vegetarianism. From the very beginning the young scholar was preoccupied with what he called “the fate of our times,” and the unifying theme of both his scholarship and his life was the prevailing cultural crisis and the destiny of humankind in the contemporary world.

At least, this is the view of Lawrence A. Scaff in his absorbing new critical study of Weber’s life and writings. Mr. Scaff believes that the familiar characterizations of Weber’s work, and descriptions of him as the founder of sociology, or the leader of the revolt against positivism, or the theoretician of Machtpolitik, and the like, are incomplete and inadequate. He writes:

As one turns from the comfort of the old and familiar to the life and thought as a whole…one cannot fail to sense a dissonance between interpretive generalizations long since take for granted and the record of actual work and accomplishment…. Even to conceive [Weber’s] essential questions arrayed along a single axis between “science” and “politics” is already to risk missing what is most important

—namely, what both Karl Jaspers and Karl Löwith sensed, Weber’s fundamental philosophical impulse, his search for knowledge of self and the specific historical character of his time. “In my judgment,” Mr. Scaff writes, “if we follow Weber’s lead in this direction—that is, toward the culture and politics of the modern age—we should be rewarded with the recovery of a much more challenging and unusual body of thought than has generally been encountered before.”

The direction taken by Weber’s early career clearly supports Mr. Scaff’s approach. In her biography of her husband, Marianne Weber tells us that the young jurist’s decision in 1894 to leave the University of Berlin, where he seemed likely to receive Levin Goldschmidt’s chair in commercial law when Goldschmidt retired, and to accept a chair in political economy at the University of Freiburg was caused not only by his indignation over the disingenuous manner in which the Prussian minister of education, Friedrich Althoff, tried to under-cut the Freiburg offer but also by his conviction that his interests would be better served by the change in discipline. He felt, she wrote, that

as a science political economy [was] still elastic and “young” compared with jurispurdence, and in addition [lay] on the boundary of the most varied scholarly provinces; from it there [were] direct connections with cultural and intellectual history, as well as with philosophical problems; and finally it [was] more rewarding for a political and sociopolitical orientation than the more formal approach of legal thought.1

In fact, Scaff writes, Weber had become increasingly interested in political economy since the Eighties. The relatively new discipline seemed to him to offer a means of achieving “a modus vivendi between theoretical work and practical activity.” It was a science that investigated “the economic and social conditions of existence” that shape “the quality of human beings,” while at the same time imposing restraint upon the currently fashionable emphasis on economic development by means of its strong national component, which sought always to identify, and take as a standard of judgment, “the permanent economic and political power interests of the nation.” Finally, political economy, in Weber’s view, “built its content on characteristics of the modern,” not least of all because theory began, he believed, with “the modern occidental type of human being and his economic action.”

The general problem that preoccupied Weber in his early writings was the relationship between changes in economic and social structures and those in political authority and rule, and the consequences of such structural changes for the conduct of life in different social strata. This concern marked his early studies of agrarian economies and their role in the rise of capitalism and found eloquent and comprehensive expression in his inaugural lecture at Freiburg in May 1895.

In this closely argued discourse, Weber argued that methods of production currently followed by the East Elbian landowners, in particular their increasing use of Polish day laborers in preference to German agricultural workers, posed a problem that could be judged only by political standards, since it involved the basic interests of the nation, the Germanness of its eastern districts. The economic preferences for Polish labor on the part of the Junkers, the class upon which the monarchy depended for the protection and governance of the state, clearly invalidated their right to continued political authority, since they no longer recognized the national interest.

Advertisement

The difficult question was into whose hands their power would fall in a time when the political will of the old liberal Bürgertum seemed broken beyond repair as a result of Bismarck’s rule, and when the lower middle class was sunk in philistinism, while the working class was bereft of “the catilinarian energy of the deed.” Despite the achievement of the period of unification, the Germans were now burdened by “the heaviest curse that history can give a race…the hard fate of being political epigoni.” The way out of this cultural crisis, Weber declared, in words clearly influenced by Nietzsche’s essay “On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life,” lay in a new political education that would wean the Germans from their prevalent eudaemonism and make them conscious of their responsibility to history and willing to embark on a Grosse Politik like that followed by Britain and France.

We shall not succeed in banning the curse under which we stand, that of being lateborn in a politically great time, unless we understand how to become something else, the forerunners of a greater one…. It is not the epochs of a glorious history whose weight ages a great nation. It remains young when it has the capacity and courage to be true to itself and the great instincts that are given to it and when its leading strata are capable of lifting themselves up to the hard clear air in which the sober work of German politics prospers, which is, however, also inspired by the earnest grandeur of national feeling.

In this address, which had great resonance in the country, not least of all because it accorded with the imperialist fervor of the age, the interrelatedness of the various dimensions of Weber’s political economy is clear, as is the primacy of his preoccupation with the cultural crisis.2

In 1897 Weber suffered a nervous collapse that forced him to take a long leave of absence from the University of Freiburg and, indeed, put an effective end to his career as a teacher, although he taught briefly at Heidelberg in 1902 and gave intermittent lectures until the end of his life. It was not until 1903 that he was able to return to his methodological studies, and these were frequently interrupted by periods of rest and trips to health resorts. Even so, thanks to his remarkable powers of self-discipline, his greatest work lay before him, and in it the emphasis on culture, always implicit in his earlier writings, became more pronounced. Scaff points out, for example, that in 1904, when Weber, in collaboration with Edgar Jaffé and Werner Sombart, assumed the direction of the Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik he wrote a preface (Geleitwort) to the new series in which he contrasted the work of the journal from that of other social science publications:

Above all, today the research domain of the “Archiv” must be fundamentally expanded, something that until now happened only sporadically and from case to case. Our journal will have to consider historical and theoretical knowledge of the general cultural significance of capitalist development as the scientific problem whose understanding it serves.

He made his own contribution to this tendency in the essays of 1905–1906 that became the second half of his study The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Here he traced the history of the ascetic ideal since the Protestant Reformation, showing its relationship to the origins of capitalism and the way in which it was finally defeated by its own projection into the external world of production, labor, and material culture, and by the relentless rationalization of capitalist development. As a result of this process, the modern individual was left a prisoner of vocational activity in a disenchanted world without meaning. In a famous passage, Weber wrote:

The Puritan wanted to work in a calling; we are forced to do so. For when asceticism was carried out of monastic cells into everyday life, and began to dominate worldly morality, it did its part in building the tremendous cosmos of the modern economic order. This order is now bound to the technical and economic conditions of machine production which today determine the lives of all the individuals who are born into this mechanism, not only those directly concerned with economic acquisition, with irresistible force. Perhaps it will so determine them until the last ton of fossilized coal is burned. In Baxter’s view,3 the care for external goods should only lie on the shoulders of the “saint like a light cloak, which can be thrown aside at any moment.” But fate decreed that the cloak should become an iron cage.4

The problem that is posed by capitalist development is, therefore, that of finding means of rationalizing or manipulating or adapting to the cultural dilemma in ways that will restore meaning and purpose to modern life. Weber pursued this theme in the section on “Religious Ethics and the ‘World’ ” in Economy and Society and, more particularly, in the “Intermediate Reflection” at the end of the first volume of his Sociology of Religion.5 Written sometime after 1909, the latter essay, apart from providing a typology of asceticism and mysticism, elaborated the conclusions of The Protestant Ethic in more abstract and generalized form, emphasizing that any system of values that accepted the transformation of the world into “causal mechanism”—the rationalized economic system, for example, which is built upon money, “the most abstract and ‘impersonal’ thing that exists”6—necessarily rejects on principle any way of looking at things that, above all, searches for a ‘meaning’ in what takes place in this world.”7 The “Intermediate Reflection,” then considered the validity of value systems that did profess to make life meaningful—in particular the religious, aesthetic, erotic, and intellectual “spheres of life activity”—and Weber gave a tentative analysis and a rudimentary evaluation of them as possible escapes from the contemporary cultural dilemma.

Advertisement

His views, necessarily sketchy in the “Intermediate Reflection,” were fleshed out in a lifetime of scholarly investigation and continuing debate with friends. He analyzed and criticized systems of world-abnegation like Tolstoy’s pacificism and the ethically dominated commitment to pure forms of democracy and socialism favored by Robert Michels and Georg Lukács, as well as Marianne Weber’s speculations about an autonomous “female culture.” The possibility of a life controlled by aesthetic ideals and criteria preoccupied him for a long time. He was powerfully attracted by the poetry and ideas of Stefan George, until the poet’s “Maximin experience,” his encounter with a fifteen-year-old boy who he believed was an incarnation of the godhead, convinced him that the George circle was little more than an absurd exercise in self-indulgence.8 Under the influence of Wagner’s music, particularly Tristan und Isolde, he concluded that music was, in Scaff’s words, “the finest and highest expression of amoral and irrational interiority,” without, however, being convinced that it, or other forms of art, had any hope of vanquishing, or even escaping, the forces of rationalization. Nor did he find much promise in the Lebenskult of eroticism which was so much a part of his time. The Webers encountered this in the circle around the aberrant Freudian Otto Gross in Munich and in the community of artists at Ascona in Switzerland—a haunt, Marianne Weber wrote, which was a refuge for all kinds of extraordinary people who had abandoned bourgeois society, anarchists, nature lovers, vegetarians, and other sectaries who wanted to realize their dreams there and create a new world order9—where Weber tried, with characteristic generosity and considerable expenditure of time and energy, to be of help to some of the troubled young residents he came to know there. He asked himself, Scaff writes, whether “the new ‘freedom,’ based on a critique of sexuality and the erotic life, [could] be anything more than an age-old hedonism,” giving none but an evanescent meaning to human existence.

Indeed, whether there was an effective escape from the iron cage at all was always, to one of Weber’s skeptical and ironic mind, questionable. In his view, a responsible person had to choose either total rejection of the world or affirmation of it as it was, and either an absolute ethics of brotherliness or a value system that would accept the relativism of actual political conditions. Every choice was accompanied by costs: one had to be prepared to live with fictions or antinomies, incongruities between the ideal and the real or what Scaff calls “the uncertainties of responsibility for consequences of action.” In modern culture there were no perfect answers, but by accepting the historical world as it had become and striving to understand it, and by resisting the temptations of inwardness and subjectivism, one might make possible the emergence of “contingently hopeful futures.” In the last analysis, Weber’s choice among the contending orders or value systems of his time was intellectualism, the reliance on scientific knowledge. He wrote in the “Intermediate Reflection,”

Although science has created this cosmos of natural causality and has seemed unable to answer with certainty the question of its own ultimate presuppositions, in the name of “intellectual integrity” it has come forward with the claim of representing the only possible form of a reasoned view of the world. Thus, the intellect, like all cultural values, has also created an unbrotherly aristocracy of the rational possession of culture, one that is independent of all personal ethical qualities of humankind.10

The decision to join this aristocracy of rational scientific enquiry, Scaff says, was one of Weber’s “most fundamental choices…[and] represented a specific, permanent and comprehensive answer to the various escape routes of modern discontent.”

The second half of Scaff’s book is given over to an account of the debates and discussions over this choice and related problems between Weber and members of his circle like Ferdinand Tönnies, Werner Sombart, Robert Michels, and Georg Lukács. Certainly the most fascinating of these chapters is that on Weber’s relations with Georg Simmel, the Berlin sociologist of culture and the author of, among other things, the famous treatise on The Philosophy of Money. The two men shared a deep respect for Nietzsche, whom Simmel was among the very first to recognize as a moralist rather than an egoist or prophet of a new superman, as a profound critic of the modern age and its incipient nihilism, and as a master psychologist of human existence. Scaff points out that it was probably the brilliant third essay of The Genealogy of Morals (“What Do Ascetic Ideals Mean?”) that inspired Simmel’s conception of responsibility for the self and Weber’s attention to the fortunes of asceticism; and one might add that Weber’s generally critical opinion of the German professoriate was surely reinforced by Nietzsche’s thunderous assaults in that essay upon the moral flabbiness of modern scholarship.11

The problems that engaged Weber and Simmel were much alike: urbanization, labor and vocation, the fate of the religious, ethical, and aesthetic systems of value, the prospect for freedom and individuality in a rationalized and disenchanted world, and other essentially cultural problems of modernity. There were profound differences in their approach, Weber being more interested in the specific, while Simmel aspired to know the world in its totality, and in its infinite variety. (Lukács reported that he once complained that there were too few categories just as there were too few sexes.) But they were at one in the questions they asked, and the biggest of these, Scaff writes, was simply,

What comes next? Should we expect affirmation of modern culture, adaptation to its many modes, an exhaustive search for alternatives, a call for new prophets, a return to old religions, the persistence of familiar wisdom (“meeting the demands of the day”), individual inventiveness (“creating ideals from within our chests”), or simply nothingness?

2.

Despite the brilliance of Scaff’s analysis of Weber’s cultural views, the personality of his subject tends to be rather obscured by the argument. The reader gets only glimpses of Weber’s quotidian existence, his likes and dislikes, his working day, his views of contemporary German politics, his controversies, and his passions. Happily these are all on display in Rainer Lepsius and Wolfgang Mommsen’s admirable edition of Weber’s letters for the years between 1906 and 1908, the first volume of letters to appear in the Weber Gesamtausgabe.

The editing of Weber’s letters involves a myriad of problems, beginning with their author’s handwriting, which has been a source of exasperation and even agony for everyone who has had to decipher it. In addition, over the years the letters have been scattered and many of them lost, while others, like those published by Marianne Weber, have survived in incomplete form. Because of the accidents of time and history, the letters to which Weber was responding have often disappeared. This is true of those of Robert Michels, for example, and of most of Weber’s correspondence with Werner Sombart and Georg Simmel. The editors have not been daunted by these difficulties. They have painstakingly restored the text of the surviving letters, provided the reader with admirable notes that explain the circumstances in which each letter was written and its motivation, supplied quotations from letters of the addressee or from other documents that illuminate the text, described contemporary events mentioned in it, and tracked down every historical allusion or literary citation. In addition, in an appendix, they have included a list, and short biographies, of all of the persons mentioned in the letters and a set of genealogical tables that is highly useful for the understanding of Weber’s letters about family affairs. Because of these editorial labors, this volume is a constant pleasure to read.

Family letters, particularly those between Weber and his wife, bulk large here, because the couple were often apart, Marianne’s interest in the women’s movement taking her to frequent conferences, and Weber’s ill health necessitating long trips to Sicily and Capri in 1906, the Netherlands in 1907, and the Riviera and Florence in 1908. These letters not only show Weber’s deep affection for his wife and his interest in her work but include a considerable amount of interesting social information, about life on the health circuit, for example, and Weber’s constant but frustrated search for places that had not yet been invaded by the automobile. One learns a good deal also about the Webers’ contacts with the erotic movement and the adventures of friends, like Else von Richthofen Jaffé—la bella peccatrice, as they called her—who were more deeply involved in it than they. Weber described the relationship that Else and her sister, Frieda Weekley (who later married D.H. Lawrence), maintained with Otto Gross, the Munich psychiatrist, follower of Freud, drug addict, and cult leader, as “die nackte Schweinerei” and when Gross submitted a paper to the Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik which was filled with metaphysical speculation, Weber, no great admirer of Freud, wrote to Else Jaffé:

Every new scientific or technical discovery still has as a consequence the fact that the discoverer, whether it is a matter of beef extract or the highest abstractions of natural science, believes himself called upon to be the discoverer of new values and a reformer of “ethics,” just as the inventors of color photography turn themselves into reformers of painting. But that these apparently unavoidable swaddling clothes have to be washed in our Archiv is not in my opinion necessary.

Gross was, he wrote on another occasion, a Trottel (addlepate) with whom he wanted as little to do as possible.

The letters to Paul Siebeck, the publisher of the Archiv, provide considerable insight into Weber’s working habits, which can only be described as hazardous for one of his precarious health. What emerges here about his editorial duties, which involved soliciting articles in the fields of political economy, social history, and psychology and then reading them and generally making painstaking suggestions for improvement and amplification, makes it difficult to understand how he was able to accomplish so much research and writing of his own in these years. The physical effort was, moreover, always accompanied by considerable nervous strain over such matters as Edgar Jaffé’s handling of the printing of Weber’s articles on the Russian revolution of 1905, which Weber claimed left him 2000 RM out of pocket because of corrections and additional printing costs. There were frequent contractual disputes and threats to resign, which never came to anything because no one could imagine an Archiv without Weber’s participation, least of all himself.

Despite his resignation from his professorship at Heidelberg in 1903, Weber remained an influential force there and in the academic profession generally, and his advice was frequently sought on appointments. He was quick to strike out at what he considered to be injustice or prejudice in the behavior of university faculties, and considered the exclusion of Social Democrats from teaching positions in German universities a “shame and a disgrace, for a civilized nation [Cultur-nation],” as he wrote Robert Michels, one of the victims of this rule. He was driven to fury by the tactics that defeated his efforts to secure a professorship in Heidelberg for Georg Simmel, like the letter from Professor Dietrich Schäfer of Berlin to a high official in the Baden Ministry of Culture that stated that Simmel was “an Israelite through and through, not only in external appearance but in his behavior and mentality” and the persistent rumors that his Berlin classes were filled with subversive foreigners.

Weber’s defense of his friends when they were unfairly attacked was immediate and unconditional—on hearing that a Marburg professor had made a slur against Michels he wrote: “I am itching in every finger to fetch that Bengel one behind the ear!”—but he was no less forthright when no personal factor was involved, as in his defense of the younger faculty of the universities against the often arbitrary behavior of the full professors. He did not hesitate to remonstrate sharply to Lujo Brentano, a man whom he greatly admired, when the Munich economist objected to demands made by junior faculty and said that a quos ego or divine threat was needed to bring them to their senses.

Among the most interesting of the letters in this volume are those addressed to Robert Michels, the young social scientist and analyst of political parties who emigrated to Italy after his socialist views made it impossible for him to secure a teaching position in Germany. Weber, the editors of this volume tell us, was interested at first only in winning Michels as a contributor to the Archiv in order to widen its political spectrum, but they became friends and continued so after Michels began teaching at the University of Turin. It was a not undisturbed relationship, and on one occasion Michels aroused Weber’s indignation by wanting to have views about the German professoriate that Weber had expressed in a private letter printed in a socialist newspaper and telling Weber that the editor had said that Weber might be afraid to allow this. Nothing infuriated Weber more than doubts about his courage, and he once challenged a man who had libeled him to a duel. But his anger on this occasion was compounded by Michels’s obtuseness in not understanding the difference between the latitude allowed in private correspondence and the scientific accuracy required of public statements. He refused Michels’s request and warned him that its repetition would end the intimacy of their correspondence.

Weber was always disturbed by the romantic and emotional components of Michels’s thinking. When Michels wrote an article on urban erotic life in which he claimed that prostitution in France was morally superior to that in Germany, Weber accused him of being “a moralist from head to toe,” adding:

You are unfair to German whores. They have their firm “ethics” just like others, and the Parisian ones seem somewhat idealized. For the rest I am in complete agreement. About the public Knutschen of German lovers I feel much the same as the Italians, although the latter are, in my opinion, all too “prudish.”

He was equally critical of the utopian and moralistic cast of Michels’s socialism, and in a long letter criticizing an essay of the younger man on “the oligarchic tendencies of society” warned him against the use of meaningless phrases like “the true will of the people” and his failure to realize that talk about revolution and the establishment of a form of democracy that would end the domination of people over people was farcical in modern conditions.

Any one who wants to live as a “modern person”—and only in the sense that he has his newspaper every day and railroads and electric trams, etc.—renounces all those ideals that hover darkly before your mind, above all as soon as he gives up the position of revolutionary action for its own sake, without any “goal,” yes, without the possibility of thinking of a goal. You are a basically honorable fellow and will by yourself…complete the critique that long ago brought me to this way of thinking and by doing so stamped me as a “bürgerlich” politician as long as the little that one as such can will, does not withdraw into the endless distance.

With infinite patience and insistent criticism, Weber sought to make a scientist out of Michels, constantly playing changes on the dictum announced in one of his letters of 1908: “Scientific work is not a labor that ‘distributes light and shadow,’ as you write—and there is no justice there—only facts and their causes.” He constantly urged him to turn his mind to the systematic analysis of institutions, and there can be little doubt that Michels’s great work, Die Soziologie des modernen Parteiwesens, owed a great debt to Weber’s critical oversight.

In German politics, the period covered by this volume saw the personal regime of Emperor William II reach its height. As one who hoped against hope for a turn toward parliamentary government, Weber in 1906 warned his old friend Friedrich Naumann, one of the leaders of the left liberal Freisinnige party, to see to it that his followers did not rally behind the Kaiser in the crisis caused by the Tangier incident of the previous year. He wrote:

The degree of contempt that our nation increasingly encounters abroad (Italy, America, everywhere!)—and with justice—is the decisive issue. Our submission to this regime of this man is gradually becoming a power issue of “world” importance for us. No man and no party, who in any sense cultivates “democratic” and at the same time “national-political” ideals, dares take upon himself the responsibility for this regime, whose continuation is a greater threat to our world position than all colonial problems of every kind.

The situation did not improve. In one of the last letters in this volume, written to Naumann at the height of the uproar over the Kaiser’s irresponsible remarks to a reporter of the English Daily Telegraph, Weber expressed the view that the conservatives were responsible for maintaining the personal regime. “Much too much is said about the ‘impulsiveness,’ etc. of the person of the Kaiser,” he wrote. “The political structure is responsible for that…. The decisive thing is that a dilettante has the threads of power in his hands, and that’s what the conservatives want.” The note of resignation was unmistakable.

3.

A month after Weber’s death in 1920, Robert Michels wrote in a Basel newspaper:

Max Weber was a very complex person: a man of strict and exact science, a scholar from head to toe who loved science as passionately as a young bride, a political economist, specialist in public law, sociologist, historian of religion, but also a practical politician, organizer, and not least possessed of a truly daemonic nature.

Michels was wrong about Weber’s political gifts, and Wolfgang J. Mommsen has demonstrated that when Weber had a chance to play a part, after the collapse of 1918, in building a new democracy in Germany, he developed doubts and convinced himself that what the country needed was a plebiscitary or Caesarist statesman on the Bismarck model.12 As for his daemonic nature, this was merely a reflection of the fatalist cast of his thinking. Lawrence A. Scaff has pointed out that Weber was apparently fond of Goethe’s poem “Daemon” and that in 1897, in a debate with Karl Oldenburg, he quoted from it in a peroration that ran:

There are optimists and pessimists in the consideration of the future of German development. Now, I don’t belong to the optimists. I also recognize the enormous risk which the inevitable outward economic expansion of Germany places upon us. But I consider this risk inevitable, and therefore I say, “So must you be, you will not escape yourself.”

Coming from one who already recognized and feared the irresponsible adventurism of the Wilhelmine regime, this degree of fatalism is off-putting, and reminds us that too many Germans before 1914 and before 1933 and before 1939 talked about their inescapable destiny. There is another passage in Goethe, at the end of his memoirs Poetry and Truth, in which he discusses daemonic natures and quotes the lines of his hero Egmont, who was one of them:

Child, child! No further! As if whipped by invisible spirits, the sunsteeds of time bear onward the frail chariot of our fate, and nothing remains for us but, with courageous composure, to grip the reins firmly and steer the wheels now left, now right, here from the cliffs, there from the abyss. Whither is he hasting? Who knows! Does anyone consider whence he came?13

But surely the point of Goethe’s drama was that, because of this fatalistic predisposition, Egmont was a foolhardy and irresponsible leader who encompassed his own destruction and that of most of his followers. One cannot accuse Weber of anything of the sort, but it is surely not too much to say that the daemonic nature that Michels attributed to him comported ill with his democratic professions.

It would be unfair to end on this sour note. Like most great men, Weber was a person of paradoxes and contradictions. He was also honest and knew his own weaknesses. Scaff tells us that he recognized his vocational imperative as an amor fati, and that he also knew that love of fate was in itself a fatality. He once wrote to Ferdinand Tönnies, “In this respect I feel myself a cripple, a deformed human being, whose inner fate is to have to answer honestly for this.”

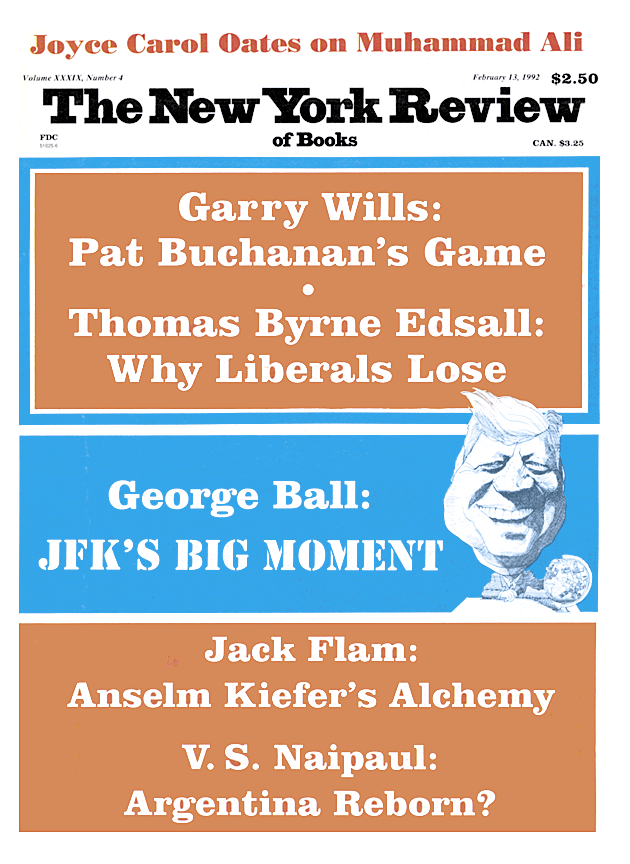

This Issue

February 13, 1992

-

1

Marianne Weber, Max Weber, Ein Lebensbild (Tübingen: Verlag J.C.B. Mohr/Paul Siebeck, 1926), p. 212. ↩

-

2

See my article “The Kaiser and the Kritik” in The New York Review (February 18, 1998), pp. 17–20. ↩

-

3

Richard Baxter, 1615–1691, the English nonconformist clergyman whom Weber regarded as the outstanding writer on Puritan ethics. ↩

-

4

Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, translated from the German by Talcott Parsons, with an introduction by Anthony Giddens (London: Unwin-Hyman, 21st impression, 1990), p. 155. ↩

-

5

“Zwischenbetrachtung: Theorie der Stufen und Richtungen Religiöser Weltablehnung,” in Max Weber, Die Wirtschaftsethik der Weltreligionen Konfuzianismus und Taoismus: Schriften, 1915–1920 (Max Weber Gesamtausgabe, Abeilung I, Vol. 19, edited by Hedwig Schmidt-Glintzer in collaboration with Petra Kolonko (Tübingen: Verlag J.C.B. Mohr/Paul Siebeck, 1989). ↩

-

6

“Zwischenbetrachtung,” p. 488. ↩

-

7

“Zwischenbetrachtung,” p. 512. ↩

-

8

Marianne Weber, Max Weber, Ein Lebensbild, p. 466. ↩

-

9

Marianne Weber, Max Weber, Ein Lebensbild, p. 494. ↩

-

10

The translation by Mr. Scaff. “Zwischenbetrachtung,” Max Weber Gesamtausgabe, Abteilung I, Vol. 19, pp. 517ff. ↩

-

11

See Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy and the Genealogy of Morals, translated by Francis Golffing (Doubleday, 1956), pp. 284ff. ↩

-

12

See Wolfgang J. Mommsen, Max Weber and German Politics, 1890–1920, translated from the German by Michael S. Steinberg (University of Chicago Press, 1984); and my article “The Kaiser and the Kritik,” The New York Review, February 18, 1988, p. 20. ↩

-

13

Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Werke, Hamburger Ausgabe in 14 Bände, edited by Erich Trunz (Munich: C. H. Beck Verlag, 1981), Vol. IV, p. 400; Vol. X, pp. 177 ff. ↩