The cult of Prester John was still going strong in 1985. A man would rise up with the sacred jewel of kingship around his neck and restore Mother Africa to her glory. Contenders were everywhere; they rushed to keep up with every controversy, like a flock of rooks, crying in the air currents, trailing gulls to a dump site. If you fired a bullet into space, you’d bring down a black leader.

I went to the Felt Forum, where the Pretender was to speak. Toward Thirty-third Street the crowd thickened and I had the dizzy sensation of being a child again, lost among legs. Surprisingly, there were few representatives from the lunatic fringe: lonely figures in quasi-military gear holding up charts showing the twelve tribes of Israel. The police shouted instructions—“Keep them off the barricades”—and their anger added to the crowd’s excitement.

Scalping began in earnest. More wanted to buy than to sell. One guy hugged his ticket and said he just had to hang on to this one. Filing into the arena, I saw the lines split up: men were directed to one side, women to the other, and for a crazy moment I thought some Islamic segregation of the sexes was to be imposed.

Instead, we were searched. Young men dressed in tight-fitting suits and bow ties, like middleweight champions at press conferences, told us to raise our arms and keep moving. Hands tapped lightly up and down every body. The mass frisking demonstrated the scale and discipline of the organization and announced to everyone that we had been transferred from police jurisdiction.

Supermarket music came over loudspeakers. I worried that my fake press pass would be challenged during a scene between one of the Pretender’s security guards and two white journalists who had settled on the steps. The guard told them they were a fire hazard and would have to move. They pretended they hadn’t heard. He made a show of getting angry, but that could not disguise his pleasure in telling them what to do. His stance said it was his turn to do some bossing around.

The two journalists gestured helplessly at the press section. All the seats were claimed. The guard told them to look for seats in the balcony. They said it was important that they be able to see. He told them it would go hard on them if he had to tell them twice. “Would you talk that way if a white man asked you to move?”

They picked up their cameras and surveyed the rows. The concrete walls were streaked with rust. One of the journalists suggested that they forget the assignment. A black woman testing her tape recorder said, “Stick around. This could be as much fun as Purim.” She obviously liked the look on their faces. “Not to worry. I’m not halakhically Jewish.”

At 7:20 PM it was announced that there were 25,000 people waiting outside. “All brothers seated anywhere in the auditorium who know how to check please come to the rostrum immediately. They must be checked immediately. You know the atmosphere that’s been created here.”

Applause for the numbers waiting outside, applause for the volunteers, applause for the tense atmosphere, applause for the further announcement that the organization had its own film equipment and high-speed duplicating machines, and still more applause that videotapes of the evening’s ritual would be available immediately.

“I just got a whiff of something disrespectful. I smell that reefer right here on this rostrum and will not tolerate this. If someone is sitting near you, tell him to put that reefer out. You can’t understand better high.” That, too, was applauded.

The members of the audience also gave themselves a big hand. They were impressed by the scene they made, the threat of potential energy that they as a body conveyed to onlookers. A large proportion of the curious and the believers probably came to experience again the surge of power they felt at protest rallies in the churches, halls, and public squares.

A similar astonishment must have greeted such mass demonstrations in the past, when the marauding voices and scattered blacks came together outside their usual precincts. Marcus Garvey, they said, had done it, had shown them what they really looked like, and though he had been forgotten by the time Malcolm X was selling sandwiches on trains, having his hair straightened in the best place in Boston, and laying them out in the Savoy Ballroom the next night, he did it, and because it was impossible to imagine Malcolm X at sixty, new “buccaneers of the street,” “dimdescended, superbly destined,” were doing it again.

Some identities were like fires in old houses. There was no grate; just a big pile of ashes smoldering away. Maybe there was a hound snoozing nearby. You put on another log. The thing was to create a hotbed of ash and the fire would look after itself, though the applewood was neither as dry nor as old as it should have been. English had become a term of abuse, even when used by the English. People would rather have gone on about their Welsh identity. Only minorities could have an identity. It was too jingoistic in others.

Advertisement

But the links with Africa had fallen away, though there were plenty of people who would try to convince you otherwise. What survived was true. Some things remained, but that in its way was as wild as saying, “I come from Kentish men,” or “That’s the Angle in me showing.”

A formerly despised people also once despised themselves, the theory went, and so there was no way to value the expressiveness of “sweating like a coon trying to write a letter” or “busy as a jump cable at a nigger funeral” when a white person said it. If you laughed, you would go to the other extreme once you’d stopped laughing, and a dog could have told you that.

“Welcome to the oppressed,” one of the night’s many warm-up acts said. “There’s a ticket for every seat. We don’t like to charge to tell the truth God has blessed us with, but we don’t charge much. When Michael was here it cost thirty dollars. Some of you have never been here because the tickets are too expensive.”

Another warm-up act: “Let’s lay some truth on the FBI agents planted in the audience so they’ll work for us. We are not poor, we are poorly organized. We don’t need talk, we need guns. I love the spirit here. I’m a born-again primitive. Your leadership told you not to come here. Either you’re not listening or they’re not your leaders. We’re going to take a bite out of this apple and spit it back at the mayor.” An exclusive invitation to the vernacular pie.

The Pretender appeared late, like a rock star. Flashbulbs exploded and made him poppy bright. He arrived onstage with his mouth working, coming in the name of Allah, who alone would give them victory over their enemies. “Who knocked Henry Ford out of the ring? The International Jew.” This was the main event: leftovers; an hour of peelings, bones, onionskins, fat.

“You may wonder why I’m smiling. I know something.” The Pretender had his work cut out for him, converting mundane ingredients into a high-caloric meal of sound bites. “The politicians call me ugly names. They are trying to undercut my magnetic attraction in my own people. They are trying to destroy my influence among you and ultimately murder me. They think they are doing God a favor and seek my death. Now, isn’t that something?” He held up both hands in an attempt to calm the storm of applause.

I remembered the thrill of a slippery kitchen floor during the lunch rush. I washed dishes. I hadn’t the time to properly scrape the plates. I flipped them at the bins. Most of the food went on the floor, and skating across the mixture of water and slops I elevated to a skill.

“What do you think will happen to America if anything happens to me?” the Pretender asked. “They say I am divisive. It has to be that way. You can’t mix Satan and God. Am I from Satan or God? If I were from Satan, this world would love me because this is Satan’s world.”

I saw stacks and stacks of dirty dishes, leaning towers of crockery, as the Pretender talked on. “The wicked are surprised and angry. Jews are going through America trying to line up blacks against me. Your excuses are ending. I am your last chance. God makes me pleasant for you to look at. This little black boy is your last chance. You can’t frighten black people the way you used to.” The cheers were furious. They had licked every pot. Somewhere a watermelon was weeping.

A journalist with snowy hair like Mark Twain’s bit down on his pipe and said, “Begin life as a con and your character can improve; begin as a prophet and you can only go downhill.”

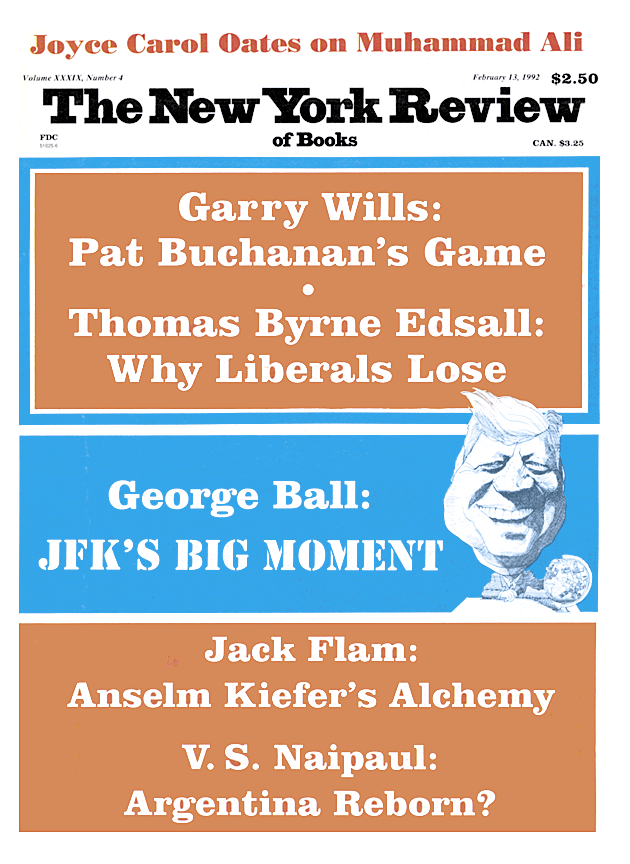

This Issue

February 13, 1992