The Hebrew Bible is so called because the Greek “ta biblia” means “the books.” These books were written during a period of more than a thousand years, from the thirteenth to the second century BCE (Before the Common Era). The canon of the Hebrew scriptures was established about 100 CE. It consists of three parts, the Torah (the Law), the Nevi’im (Prophets), and the Ketuvim (Writings). In 450 BCE the prophet Ezra read to the people of Israel the Torah, that is, the first five books of the Hebrew scriptures, Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. His reading established the primary text for Jews. In the first century CE certain rabbis consolidated the Torah with the Nevi’im (the books of the Prophets, Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings) and with the Ketuvim (diverse writings that included the Psalms, Song of Songs, Proverbs, Job, Ecclesiastes, Ruth, Esther, Ezra, Chronicles, and Daniel). These three groups of writings constitute the Hebrew Bible, the Tanakh.

Scholars of the Tanakh claim to be able to distinguish, on the evidence of vocabulary and style, four authors or schools of authors: J, so called because he or she or they used the divine name Jehovah or Jahweh; E, because this writer called God Elohim; D, author or authors of Deuteronomy, and P, Priestly, author or authors of most of Leviticus. In addition to these books there is midrash, the rabbinic practice of commentary, exemplification, narrative interpolation so closely related to the Torah that it can hardly be separated from it. Jews who read the Bible in this spirit and articulate their interpretation of it in detail are engaged in midrash.

Christians refer to the Tanakh, invidiously, as the Old Testament, but their access to it is not to the Hebrew or Masoretic text but to a Greek translation, the Septuagint, made in Alexandria between the third century BCE and about 132 BCE. Translations into Old Latin of the Septuagint and of the Greek of the New Testament were superseded by Saint Jerome’s Latin version in the last decade of the fourth century. Jerome had good Latin and Greek, and he learned enough Hebrew to decide that the Septuagint was unsatisfactory. His Latin translations gradually took hold, despite the fact that Augustine preferred the Septuagint, and they became by the beginning of the eighth century the basis of the Vulgate. The New Testament was established as a gathering of twenty-seven writings: the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, Epistles of Paul, John, and Peter, and the Acts of the Apostles. These circulated not only in Greek and Latin but in Syriac, Arabic, Coptic, Armenian, and many other languages. In 1516 Erasmus produced an edition of the Greek text of the New Testament with a new Latin translation that held the field for centuries. In England it gained enough credence to become the basis of the King James or Authorized Version, translated in 1611, although that version was also much indebted to William Tyndale’s of 1525. Roman Catholics, or some of them, prefer the Douai-Rheims version (1582–1610) or one of several modern translations, probably Ronald Knox’s New Testament (1945) and Old Testament (1949).

Like any other document of religious import, the Bible may be read in various ways. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, the faithful read it as holy writ, divinely revealed vision of the world, source of belief, morality, doctrine, and the sense of community. Outsiders, and insiders who don’t believe, read it as a good book, a sublime poem, but not the Good Book. I don’t think they take it as pure fiction but as sayings, lore, moral parables, what one might murmur in the middle of the night without being accountable in the morning: “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion.” It is also possible to read it opportunistically, as I once read the Brihadaranyaka-Upanishad in the hope of understanding what Eliot did with it in the fifth part of The Waste Land.

The modern phase of the literary interpretation of the Bible began with a few pages in Erich Auerbach’s Mimesis (1946). In a chapter otherwise concerned with narrative methods in Petronius and Tacitus, Auerbach drew attention to the episode in Mark (14:54–72) in which Peter denies Christ three times. Analyzing the use of dialogue, Peter’s emergence as a tragic figure despite his lowly station, and Mark’s telling the story not externally but as if he were “at the core of what goes on,” Auerbach argued that the scene “fits into no antique genre.” It is

too serious for comedy, too contemporary and everyday for tragedy, politically too insignificant for history—and the form which was given it is one of such immediacy that its like does not exist in the literature of antiquity.

But Auerbach didn’t say a word about the episode as part of a larger story calling for belief. At the end of the chapter he made an abrupt and to me implausible comment about an alleged antagonism in the Christian view of reality between sensory appearance and meaning. But he left readers free to read the chapter in Mark as if it chiefly belonged to the history of narrative method.

Advertisement

I don’t see any objection to Auerbach’s procedure. It is impossible to control the way a particular reader chooses to read the Bible. Priests offer interpretations, but can’t enforce them. The authority claimed by the Roman Catholic Church in the interpretation of the New Testament applies only to its members. On the other hand, those who read the Bible as literature shouldn’t get cross with those who take it as gospel.

The World of Biblical Literature is Robert Alter’s latest attempt to “fashion a new literary approach to the Bible.” It takes its place beside his earlier books, The Art of Biblical Narrative (1981), The Art of Biblical Poetry (1985), and the book he and Frank Kermode edited, The Literary Guide to the Bible (1987). The new book reprints two of Alter’s chapters from the Guide, three of his essays from Commentary, and four new essays on various aspects of the Bible as literature. Literary appreciation of the Bible, he maintains, “does not automatically contradict belief in the inspired character of the text, but it can manage quite comfortably without reference to belief.” This isn’t clear to me. It could mean that literary appreciation at some point or in some unautomatic way contradicts belief. I wish Alter would settle for the ecumenical position of saying that he chooses to read the Bible as a sublime poem and feels comfortable in doing so, but that he defends the right of other people to make a different choice.

But then he would have to give up the privilege of being testy with Jacob Milgrom, for instance, one of the authors of The JPS Torah Commentary (1989), who claims that his commentary on Numbers “offers reliable support to those who believe that this book and the Torah at large were divinely revealed.” Milgrom’s statement seems to me unexceptionable, since it allows for those who don’t believe anything of the kind. But Alter is spoiling for a fight:

It is hard to imagine what in his commentary, including the citation of Jewish sources, he thinks might confirm this claim. In fact, his painstaking accounts of trial by ordeal, ritual contamination by corpses and menstruants, hovering miasmas of impurity, the rite of the scapegoat, and much else bring us almost uncomfortably close to a thoroughly alien world in which pagan and magical notions have undergone no more than a first phase of monotheistic transformation.

I’m sorry that Alter has been made almost uncomfortable, but he has himself, as much as the Bible and Milgrom’s commentary, to blame. He is not in a position to know why other people hold their beliefs or what those people regard as sufficient reason for holding them. He’s always ready to lose his urbanity when he realizes that some people are not men or women of the secular Enlightenment. In this mood he sounds like Sir James Frazer in The Golden Bough huffing and puffing over the discovery that some people don’t think and act like Victorian gentlemen. Falling for the most hackneyed version of the Zeitgeist, Alter says that “at this late date in the process of secularization” the Bible doesn’t exert much moral pressure:

Given the twin erosion of plain knowledge of the Bible and of belief in the Bible as divinely revealed truth, the notion that the Bible has real prescriptive authority in governing our moral and political lives would seem to be restricted to fundamentalist groups. There are, of course, substantial numbers of nonfundamentalist Christians and Jews who try to take the Bible seriously, but in most instances they would ultimately fail the test of according prescriptive authority to Scripture. He could have left well alone, but he has talked himself into the surly position of saying: “I’m not a believer, so you’re not to be one either.” By “substantial numbers,” incidentally, I assume he means “millions,” the millions of people throughout the world for whom the Bible is the sacred book. These are the people Michel de Certeau had in mind in his L’Ecriture de l’histoire (1975), when he wrote of Jews making Scripture the substitute for the Second Temple, which was burned in 70 CE. The Bible, Certeau said, “takes the place of lost prophetic speech.” The philosopher Emmanuel Levinas has also written tenderly of those who “love the Torah more than God.” Alter’s use of “our” in the passage I’ve quoted and of “we” in every chapter demeans the experiences which Certeau and Levinas respect. “Our” and “we” are accurate only if Alter is addressing atheists, Low Church Protestants, and Jews who don’t believe or practice the faith.

So he reads the Bible as literature. Literary style, he says, “is an exercise of the expressive resources of language that seeks a nuanced precision beyond the reach of ordinary usage and at the same time exhibits a repeated delight in the sheer shaping of its materials, which is in fine excess of the occasion of communication.” The excess emerges “from the writer’s vivid intuition of a superabundance of possibilities suggested by the creative associations of his literary medium.” This has been the guiding axiom of Alter’s best secular criticism, a working principle that has served him well in many books and now in parts of this one. He wants the Bible to be another great poem, like the Iliad.

Advertisement

It is not surprising, then, that he becomes strident when he reads, say, Harold Fisch’s Poetry with a Purpose and sees Fisch arguing that God in the inscrutability of his absolute purposes is implicit in all biblical texts. Alter wants to see the biblical writers turning away from such divine opacity and taking pleasure in the internal possibilities of the medium, the Hebrew language. Sensitive to the practice of good writing, he has not found it necessary to go in for much theoretical nicety. He persuades by example, especially examples of excess, play, and copiousness. But the distinction he makes between ordinary usage and literary usage is hard to sustain. In religious literature especially, a writer may see possibilities of excess but may judge them temptations to be rejected, because saving his soul is more important than writing a poem.

Reading the Bible as literature, Alter is interested in its narrative procedures, imagery, syntax, the literal and the figurative elements, repetition, the passage from one perception to a significantly different version of it. One of his finest essays is a study of differences between the several instances of Annunciation in the Old Testament, beginning with Genesis 18, where the promise that Sarah will bear a child is made by the Lord to Abraham and overheard by Sarah. Alter notes—a point made by the great medieval commentator Rashi—that the Lord doesn’t tell Abraham what Sarah is thinking about him or that she’s been lamenting the loss of sexual satisfaction. Alter loves to move among such details, as if they were transitions in a secular play.

Alter’s Hebrew is evidently strong, and he is especially alert to the implications of a word or a phrase used in different contexts. His commentary, for instance, on the reunion of Jacob and Esau in Genesis 33 turns on the repetition of the word berakhah:

The irony of the scene is brought to a sharp point by Jacob’s use of a single brief phrase that echoes an exchange at which he was not present, the dialogue between Isaac and the frustrated Esau in Genesis 27. For when Jacob here finally brings himself to address his brother in the second person, he says, “Please take my blessing that has been brought for you” (Gen. 33:11). Now the term for blessing, berakhah, also means “gift,” and that is obviously the sense in which Jacob is using it here. The writer chooses this term (there are at least three other biblical words that mean “gift”) because through it Jacob is made to reverse what Isaac said twenty years earlier to Esau, “Your brother came in deceit and he took your blessing” (Gen.27:35).

Alter has many commentaries equally illuminating: on passages in the Psalms, Esther, Judges, and other books. He is a very good reader. I just wish he were a little more tolerant.

Alter’s reference to “our fundamentally secular assumptions about literary expression” would exclude Burton L. Visotzky. For the past four years Rabbi Visotzky has taken part with other scholars in a Bible study group at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York: their text has been Genesis. Reading the Book is a description of that experience, with particular emphasis on “the homiletical exegesis of Scripture—the ‘reading out’ of moral lessons of the age from the Bible.” Visotzky’s method is to cite a difficult semantic puzzle in the Bible, resort to midrashic commentaries on it, and then add his own mite. It is not clear what he believes, except that he isn’t a fundamentalist. I’m sure he doesn’t impose his beliefs on his colleagues in the study group. He makes much of reading the Bible in a community, and of approaching it with an open mind: reading it then becomes “a pleasurable and meaningful exercise.” I’ve heard the same claim made for aerobics. But I’m ready to believe that taking part in Visotzky’s study group is a splendid experience.

I wonder, though, why he finds it desirable to write this book in a relentlessly breezy, wisecracking style. Surely he knows that the questions he raises are interesting enough to hold one’s attention without the distraction of Henny Youngman chatter. The passages Visotzky interprets in detail include the story of Abraham, Sarah, and Isaac, the reunion of Jacob and Esau, the death of Moses, the sins of Nadab and Abihu, the Creation, and Adam and Eve. Happily, when he concentrates his mind on these matters, he puts aside his talk-show manner. He has fine commentaries on the three discrepant versions, in Genesis, of the creation of Eve, or of Adam and Eve. He asks good questions: Why did God create Adam? And to whom did God say, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness”?

Visotzky favors the notion that God created humanity “out of a divine need for companionship.” A divine need seems to me a contradiction in terms or at best a presumption on Visotzky’s part. The fact that I have needs doesn’t entail God’s having similar ones, or indeed any. But the hard question, which Visotzky doesn’t really deal with, is the nature of belief. What it means to believe in God, he doesn’t offer to say. The philosopher Gabriel Marcel proposed a distinction between “belief in” and “belief that.” “Belief that” is assent to a statement or proposition as true. The content of the belief is open to verification or disproof. “Belief in” is an act of testimony to the believer’s manner of being; an act of faith or trust, a commitment or attestation. As such, it is not subject to confirmation or disproof. If I believe in God, the Father Almighty, Creator of Heaven and Earth, that belief can’t be confirmed or denied: it is immune to the production of evidence. On the issue of belief, all I can divine from Reading the Book is that God is whoever is responsible for the particular acts and sufferances named Adam, Moses, Abraham, Isaac, Sarah, and so forth.

I assume that a meeting of Visotzky’s Bible study group might begin with someone asking, “What’s all this about Creation?” Visotzky would then quote various rabbis on the subject, including Rabbi Jeremiah, who held that “Adam was androgynous, that is, having male and female sexual characteristics, just as God must have had the aspects of both masculinity and femininity.” That seems to me a blatant instance of “belief that”: it states a proposition and asks me to accept it as true. I can’t accept it. I can’t take seriously a sentence that tells me what qualities God must have had. But we are already launched into the seminar.

Visotzky is happiest when he’s talking about detail. The big picture he takes for granted. For instance: there are four references in the Bible to the deaths of Nadab and Abihu, the elder sons of the high priest Aaron, brother of Moses; two in Leviticus, two in Numbers. The first, in Leviticus 10, says that the boys “offered strange fire before the Lord, which he commanded them not.”

And there went out fire from the Lord, and devoured them, and they died before the Lord.

What was their offense? Visotzky consults “my colleague in Jerusalem, Dr. Avigdor Shinan,” and comes up with twelve possible reasons. I forbear to list them. But they are all subjected to the consideration that God should be like you and me and it’s a pity he hasn’t made himself clearer. Visotzky’s conclusion, reached with much semantic verve, could hardly be more accommodating; it is that “the Bible itself has varying opinions about the worth and nature of humanity.”

Like Alter, Visotzky is not troubled about the question of authorship. In this respect they differ from Leslie Brisman, who pursues J and E as if someone’s life depended upon Brisman’s getting the two identities right. He argues for “a truly literate and literary composition of Genesis”:

By literate I mean to suggest the possibility of one author actually able to read a text of another author, just as the author of Matthew could read the Gospel of Mark (most scholars believe) or the talmudic midrashist could read the text of the Pentateuch.

By “literary” Brisman means that the motive for a new poem is an old poem; the universe, as Borges notes, may be called the library. A social, religious, or political impulse is not to be looked for. Brisman claims to be writing literary criticism under these assumptions. He notes two possibilities. In one “a character more or less to be identified with the author of the P strand reacted to a composite of the J and E texts.” In the other, “a character more or less to be identified with the author of the J strand reacted to a composite of the E and P texts.” Brisman votes for the latter; he thinks it has more to commend it “for the understanding of the Bible as literature.”

Leaving aside Harold Bloom’s speculation that J might be a woman, Brisman calls him Jacob, “after the character in Genesis who is his special hero and representative.” Brisman also assigns to E a lot of the material commonly given to P, and he calls the enhanced E Eisaac, a mixture of Isaac and E (for Elohist). Nothing of this is clear to me except that Brisman has another reason for calling J Jacob—so that he can have Jacob wrestling with the E text as dramatically as the other Jacob wrestled with the angel, E’s God. Much sport is made, halfway through the book, with the linguistic coincidences of wrestling, wresting, and resting. Brisman arranges to have Jacob the writer die with the death of Jacob the character.

I’m not sure that Brisman’s claim to literary criticism holds good. He has drawn two sketches of putative characters who are very different. Eisaac is generally a slow fellow, though the emotions available to him include “piety, sublimity, and decorum.” Jacob is far more brilliant, more daring than Eisaac, but his taste is not impeccable and he is addicted to punning. Never a dull sentence when Jacob takes to composition. In a moment of sublimity Eisaac writes: “God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them” (Genesis 1:27). Reading this, Jacob won’t leave a good conceit alone, enough is never as good as a feast of words for him. So he adds in Adam’s voice: “Now this, at last, is bone of my bone, flesh of my flesh; this thing we’ll call wo-man because she was taken from man” (Genesis 2:23). In Words with Power Northrop Frye deplored the pun by which the Hebrew word is, which is explicitly male, lets Adam etymologize the word issa as meaning “drawn out of a man.” So the ideology of male supremacy began. But Brisman thinks Jacob’s intervention quite wonderful:

Where Eisaac’s metaphor points beyond itself to sage and serious notions of what it means for man to be created in the image of God, Jacob’s jest ironically reminds us not only of “biology to the contrary” but of all we know about the relations between the sexes that cannot be encompassed by so neat a paradigm. Both are extraordinary passages, one a supreme Yeatsian “monument of unaging intellect,” the other an ever-fresh reminder of [Wallace] Stevens’s quip about Eisaacic ideals: “Beauty is momentary in the mind—/ The fitful tracing of a portal; / But in the flesh it is immortal.”

I think I see, as through a glass, darkly, what Brisman has in mind, but I’m not sure that so much should depend upon the acoustic emergence of “immortal” from “portal.” There is a touch of old Jacob in Brisman, too.

But how does he know when the voice is Jacob’s and when Eisaac’s? By ear, mostly. Brisman takes account of differences of vocabulary, but he admits that these are not decisive. Considerations of relative merit are no help either. Brisman doesn’t claim that Jacob is a greater writer than Eisaac or that he ever wrote anything more sublime than Eisaac’s story of the flood, the covenant, and the rainbow (Genesis 6:17 to 9:17). Still, Brisman is on Jacob’s side, even to the extent of insisting that a damaging verse, such as verse 12 of the Hagar story in Genesis 21, is not in his voice. This is never a convincing argument, as we know from the fact that great writers sometimes write badly.

The Voice of Jacob is an outbreak of midrash, a Jacobic commentary on myths Brisman claims to recognize as Jacob’s. It wouldn’t demean the book to call it a fiction and to admire the virtuosity with which Brisman has added chapter to chapter in the process of imagining what it would mean if an episode in Genesis were to be heard as Jacob’s tale rather than Eisaac’s. The question of belief isn’t raised. Brisman wouldn’t be at all dismayed if a voice spoke out of the whirlwind to inform him that Abraham never existed. The Voice of Jacob is a psychobiography of two notional writers locked in combat for the blessing of God or, if you prefer, for the applause of readers. Very fine it is, too.

The chapter on Rachel’s theft of the household idols, the teraphim, for instance, is so vivid that I find myself ceasing to care whether Brisman is right or not and caring instead for everything else in his sentences. Recall that when Jacob, Rachel, and Leah ran off from Laban’s house, Rachel secretly stole Laban’s teraphim, or household religious objects. Brisman says that the teraphim “are generally understood to be instruments for divination or idolatry.” I don’t know why Rachel wants to steal these things from her father. Brisman quotes E.A. Speiser’s suggestion that “she was helping secure for her husband the tokens of his legitimate right to Laban’s fortune.” But why then doesn’t she tell Jacob? When Laban pursues Jacob and his family and searches Rachel’s tent for his property, he doesn’t find anything. Rachel has hidden the teraphim among bits of “the camel’s furniture” and stays sitting on them, pretending to Laban that she is menstruating and can’t decorously stand up. Brisman considers the several possible explanations but he leaves us free, for once, to interpret the story as J’s or E’s:

Who wants to accuse Rachel of being a witch? Not Eisaac, for whom she is the spotless and true wife of a spotless and true Jacob—Father Jacob. Not Jacob the writer, at least not openly. Jacob’s Cain is (I have suggested) ordered by Yava [God] to sit there, crouched before but not in sin. Rachel is not taking orders from anyone, but she too just sits there, defying both her father and her husband’s vow of death to the offender. If we view her with Eisaacic eyes, her defiance has to be reinterpreted as care in a righteous cause; but if we view teraphim-bearing Rachel as a Jacobic creation, she emerges as an emblem of defiance of the very piety, the very purity, of the story in which she was placed.

I hope I have made it clear that Brisman’s book is an intellectual detective story rather than a book of explanations. Brisman is a learned and versatile scholar, an ingenious writer. He expects his readers not only to be interested in pursuing J and E but also to be quick on their feet in following the clues.

Ricardo J. Quinones is as learned as anyone, but he doesn’t go in for flourishes. His book, an essay in comparative literature, is a study of Cain and Abel and the various forms in which that first fratricide has been enacted in literature and drama. It is a major theme, as Hopkins recognized in “The Wreck of the Deutschland”:

From life’s dawn it is drawn down,

Abel is Cain’s brother and breasts they have sucked the same.

Roland Barthes went so far as to say, in “The Struggle with the Angel,” that the Old Testament “is less the world of the Fathers than that of the Enemy Brothers.”

The story of these brothers begins in Genesis 4 with the Lord creating the division between Cain and Abel. But a nuance of it begins in Rebecca’s womb. In Genesis 25 the Lord answers Isaac’s petition, and Rebecca is made fertile. Twins “struggled together within her,” and when she asks why, the Lord answers:

Two nations are in thy womb, and two manner of people shall be separated from thy bowels; and the one people shall be stronger than the other people; and the elder shall serve the younger.

The twins are Jacob and Esau. The first-century Jewish philosopher Philo, as Quinones points out, fixed upon the Lord’s answer to Rebecca in support of his contention that Cain and Abel also represent opposing principles. In a treatise, “On the Cherubim,” which digresses to consider the story of Cain, Philo identifies Adam with Mind and Eve with “Outward Sense.” Mind, having acquired the faculty of Sense and therefore having laid hold of bodily things, “was filled and puffed up with unreasoning pride, and thus thought that all things were in its own possessions and none belonged to any other.” It is this willfulness in human beings, according to Philo, “which Moses expresses under the name of Cain, by interpretation: possession, a feeling foolish to the core, or rather impious.”

Philo started this interpretation, and Ambrose purloined it. In a homily on Cain and Abel he distinguishes the two types:

There are two schools of thought…. One of them attributes to the mind itself the original creative source of all our thoughts, sensations, and emotions. In a word, it ascribes all our productions to man’s own mind. The other recognizes God as the Artificer and Creator of all things. Cain is the pattern for the first, Abel for the second.

In The City of God Augustine develops the idea further. Cain is the earthly city, Abel the city of God. In Contra Faustum Manichaeum he develops it invidiously, identifying Cain with the Jews who put Christ to death. “Abel, the younger brother, is killed by the elder people of the Jews. Abel dies in the field; Christ dies on Calvary.”

Quinones is helpful on every such aspect and variant reading of the story. He carries his learning gracefully. Over a remarkably wide range of literatures, he is informative on the unregenerate Cain, envious Cain, Cain the sacred executioner, and in the nineteenth century the transformed Cain, Byron’s hero, the Cain we are supposed to recognize as our contemporary. Along the way, Quinones has persuasive things to say about the forms in which Cain and Abel keep turning up; not only in Philo, Ambrose, and Augustine but in Dante, the Corpus Christi plays, Machiavelli, Shakespeare, Byron, Melville—a splendid chapter on Billy Budd—Wells, Conrad, Hesse, Unamuno, Tournier, and many other writers.

The most provocative part of The Changes of Cain is the section in which Quinones considers the modern transformation of Cain into a hero. The crucial writer here is Byron. In the verse play Cain (1821) Byron dealt with the brothers by reducing Abel to a bourgeois citizen and imagining Cain as a compound of biblical killer and Faust. “In Byron’s version,” as Quinones says, “Cain becomes the heroic quester, the dissatisfied so-journer.” “Wilt thou teach me all?” Byron’s Cain asks Lucifer. Byron told his publisher John Murray that Cain killed Abel out of “rage and fury against the inadequacy of his state to his conceptions”; a brilliant remark, pointing to Cain’s distinctive form of vanity. Lucifer urges him to

Think and endure and form an inner world

In your own bosom, where the outward fails.

Quinones takes these gestures more seriously and more sympathetically than I can. They seem to me as specious as Satan’s posturings in Paradise Lost. But I can see that Quinones needs Byron’s Cain as an early type of the consciousness he finds pervasive in the literature of modernism. In Mapping Literary Modernism (1985) and now in The Changes of Cain he develops a conception of modernism I’m sure many readers find entirely persuasive:

The traditional Cain, the original schismatic, has a divided consciousness. In modernism, this sense of division becomes a positive quality, indicative of superior alertness. It means not only complex awareness, but also a correlative respect for the conjunction of the many forces of life. Stylistically, the complex central consciousness, with a varied and complex emotional register, is the most distinctive attribute of modernism, both in fiction and in poetry.

This is an accurate description of an important feature of modern literature and philosophy: we see it in Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Mallarmé, Bergson, Pater, Yeats, Conrad, Lawrence, Eliot, Joyce, Valéry. But Quinones’s decision to make Byron’s hero the type of modernism, first exemplar of an ideology of consciousness, has some consequences that I regret. It encourages him to interpret the literature of modernism in unnecessarily lurid terms and to bring to bear upon it a commentary relentlessly melodramatic. He does not sufficiently question the ideology of consciousness or ask what is entailed by the attempt to make consciousness account for the whole of one’s experience. It would be possible, and in my view better, more equable, to start a consideration of modernism not with Byron’s Cain but with this famous passage from Emerson’s “Experience”:

It is very unhappy, but too late to be helped, the discovery we have made that we exist. That discovery is called the Fall of Man. Ever afterwards we suspect our instruments. We have learned that we do not see directly, but mediately, and that we have no means of correcting these colored and distorting lenses which we are, or of computing the amount of their errors. Perhaps these subject-lenses have a creative power; perhaps there are no objects. Once we lived in what we saw; now, the rapaciousness of this new power, which threatens to absorb all things, engages us.

I don’t take this as gospel but it is a civil text for virtually every aspect of the modern literature that Quinones has in view, and it is blessedly free of the Byronic glow.

Quinones brings his book to a contentious conclusion. Not only is Cain the type of the “complex central consciousness” in modern literature; but he embodies a secular mind even more serious than the religious mind it has displaced. “The final value of the Cain-Abel story in the modern world,” Quinones claims, is that “the seriousness and the scope of the drama that the issues of heaven and hell once provided in the classical Christian epoch are part of the contest within the person of Cain in the modern epoch.” I am not convinced. Indeed, as Stephen Dedalus says to Deasy, “I fear those big words”: classical, Christian, epoch, modern. I don’t really believe, much as I feel the rhetorical force of Quinones’s book, that modern secular people are more serious than modern religious people. What would constitute evidence for this claim? I don’t see why Quinones wants to offend people who choose to live their lives in religious terms, in community and prayer. Why not leave them alone?

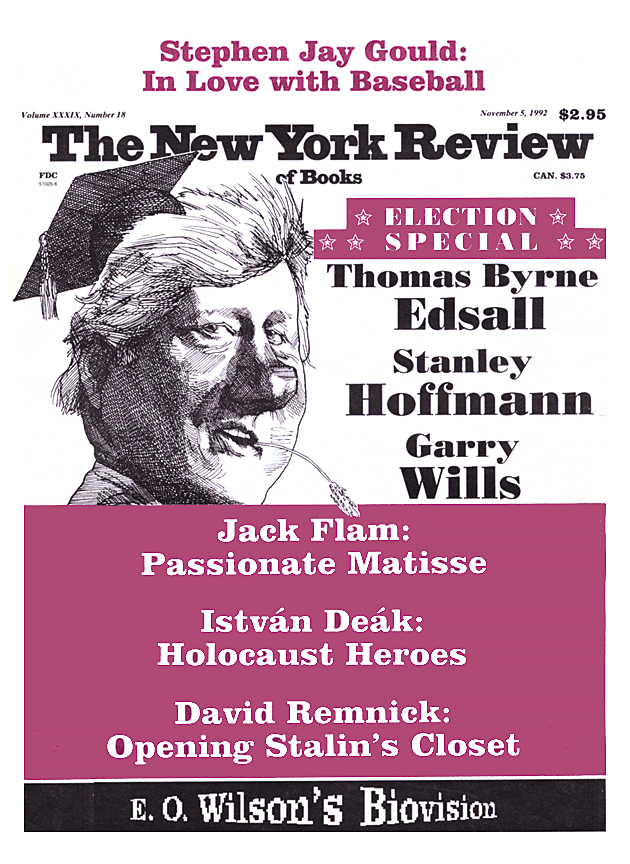

This Issue

November 5, 1992