To most Americans Finland is a strange and remote country. When they think of it they imagine a largely empty landscape: frozen snow-smothered forests, gray rocky shores, icy lakes, and black rivers pass before their inner eyes to the accompaniment of the melancholy tone poems of Sibelius. Some, though, have a more benign vision. Because they know the children’s stories of Tove Jansson, they see Finland as bright with birds and flowers, and inhabited by fantastic creatures: the Moomintroll family and their sometimes charming, sometimes difficult or even obnoxious neighbors, so different from us in appearance yet so much like people we already know.

Today Moomintroll is famous almost all over the world; his adventures have been translated into thirty-three languages, and in England he has been the hero of a comic strip and a television series. But in America, until very recently, he was unknown. Now, however, his adventures are becoming available here. The first four in the series (Comet in Moominland, Finn Family Moomintroll, Moominsummer Madness, and Moominland Midwinter) have just appeared, and more will follow.1

Tove Jansson, the creator of Moomintroll, is probably the best-known writer in Finland—not only for her children’s books, but for her fine stories and novels for adults, one of which, Sun City, is set in an upmarket retirement home in Florida. She is also a successful artist who illustrates her own work with deceptively simple line drawings.

Jansson was born in 1914 of Swedish-speaking parents settled in Helsinki. Both were artists: her father, Viktor, was a well-known sculptor. Her mother, Signe, was not only a gifted illustrator who designed two hundred Finnish stamps, but a famous storyteller. Tove Jansson inherited their talents. At fifteen she entered art school: later she studied art in Germany, Italy, France, and London. Her first, brief, Moomintroll tale appeared in 1945. It was followed the next year by Comet in Moominland and then by eight more full-length Moominland books. Jansson, who has never married, spends part of the year in Helsinki and the rest on a remote and beautiful island in the Gulf of Finland where her family has gone in the summers since she was a small child. The island appears both in her adult stories and in Moominpappa at Sea.

The author of the only book about Tove Jansson in English has compared the world of Moomintroll to that of A. A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh.2 There is something to be said for this, though Jansson, by her own account, did not read the Pooh books until long after she had created Moomintroll. Perhaps the resemblances are the result of what a folklorist would call polygenesis: similar human situations tend to produce similar stories.

Tove Jansson’s characters, like Milne’s, are highly individual creatures, part human and part animal and part pure invention, living in a remote and peaceful rural world. Jansson’s simple language, comic gift, and down-to-earth relation of odd events all remind one of Milne; so does her love of the countryside and the high value she places on affection and good manners. Like Milne, she is a humanist; and like him, though she writes for children, she deals with universal issues.

Some of Jansson’s characters also recall Milne’s. Her hero, Moomintroll, shares with Pooh his good nature, love of adventure, and innocent trustfulness. Though on first glance Moomintroll suggests a toy hippopotamus, his plump, pear-shaped body, short legs and arms, stand-up ears, and quizzical expression also make him look rather like E. H. Shepard’s drawings of Pooh. Perhaps, though, it is not so much that they resemble each other, as that both of them look like small children.

In Tove Jansson’s earliest books Moomintroll, like Pooh, has a small and timid companion. Moomintroll’s friend is called Sniff, and somewhat resembles a kangaroo. Sniff, however, is a less attractive character than Piglet. He is self-centered and dazzled by wealth, and in later books he becomes less prominent and finally disappears.

Misabel, who appears for the first time in Moominsummer Madness (1954), initially seems like a female version of Eeyore. (“Everything’s gone wrong for me, simply everything,” she declares upon her first appearance.) But whereas Eeyore remains perpetually gloomy, Misabel’s self-dramatization of her own unhappiness is eventually transformed into theatrical talent, and she becomes the leading lady of a floating theater. In Tove Jansson’s books, unlike Milne’s, it is possible for characters to change.

There are important differences between Moomintroll’s world and that of Pooh. The setting of Milne’s books is limited: a few acres of Sussex downs and woods. The imaginary Moomintroll landscape, on the other hand, stretches from the Lonely Mountains in the north and east to the villages south of Moomin Valley and the remote islands in the western sea. The world of Moomintroll is also less sheltered than that of Pooh. It contains parks and orphanages and prisons and astronomical observatories, lighthouses and telephones and fishing boats. It is much subject to natural disasters: not only floods and high winds (which also occur in Milne) but violent snowstorms, deadly cold, earthquakes, the eruption of a volcano, and a near-collision with a comet. The difference between the climates of southern England and Finland is also reflected in the books. Tove Jansson’s characters spend much time simply trying to keep warm and dry.

Advertisement

Another, and perhaps central difference between Milne’s world and Jansson’s is that the Pooh stories depict an ideal society of friends, while the Moomintroll tales portray an ideal family. And whereas Milne’s world is ruled by a male, Christopher Robin, Moomin Valley clearly centers around Moominmamma.

Milne’s model for the world of Pooh, apparently, was the boy’s school run by his father. All his characters are male, with the exception of the fussily maternal Kanga, who can be seen as the school nurse or matron. Jansson’s stories, on the other hand, contain many strongly individualized female characters. It must be admitted, however, that this is true mainly of her later books. In the first two tales of the series, the only female besides Moominmamma is the featherbrained Snork Maiden. Apart from her affection for Moomintroll (whom she almost exactly resembles except for her bangs), the Snork Maiden is only interested in her own appearance.

In the later Moominland books there are several very attractive female characters, including Mymble, Little My, and Too-ticky. Instead of displaying the stereotyped feminine emotionality and vanity of the Snork Maiden, they are more rational and detached than the male characters. Little My, especially, is almost frighteningly unemotional. In appearance she resembles a plump little girl with a blonde topknot, and though brave, resourceful, intelligent, and psychologically perceptive, she is not especially affectionate and seems to have no need for other people. She also has no illusions about herself. In Moominland Midwinter (1957), when a little squirrel freezes to death, Moomintroll comments that Little My doesn’t feel sorry. “No,” says Little My. “I can’t. I’m always either glad or angry.”

Too-ticky, another semihuman character, though as independent and practical as Little My, is more complex. Jansson has said that Too-ticky was based on her longtime friend, the artist Tuulikki Pietila, whom she met in 1950 when she was feeling over-worked and depressed. It was Tuulikki Pietila who taught her to have a more relaxed attitude to life and take things as they came. This is what Too-ticky teaches Moomintroll in Moominland Midwinter, when he leaves the cozy house in which his family is hibernating and ventures out into the terrifying Finnish winter. With Too-ticky’s encouragement he gradually begins to enjoy himself: he tries skiing, and sees the Northern Lights.

When the first book in the series, Comet in Moominland (1946), appeared Finland was just emerging from the dark years of World War II, during which the country was invaded by Russia and occupied by Germany. It is perhaps no surprise that it tells of a desperate and dangerous time. In the course of the book, Moomintroll and his friends discover that a huge comet is approaching the earth. Gradually the rivers and oceans dry up; the world becomes hotter and hotter and darker and darker; there are tornadoes and plagues of grasshoppers. What keeps the story from being frightening or depressing is Moomintroll’s optimism and love of adventure, and his well-placed confidence that whatever happens, Moominmamma will be equal to it.

In this book, as in those that follow, Moominmamma is the stable center of the story. She is the perfect mother: always kind, understanding, and forgiving, an unending source of warmth and love and food. It is she who solves problems, gives advice, comforts the distressed, and generally holds the family together. Moominmamma believes that “all nice things are good for you,” and wherever she is, even on a desert island or in the midst of a disaster, there is always lots to eat: raspberry juice, pancakes with homemade jam, birthday cake, blueberry pie, coffee, sandwiches. Jansson has said that Moominmamma was based upon her mother, Signe, and that her mother’s stories were the beginning of the Moomintroll tales.

Moominmamma cares not only for her family but for any stray creature that wanders onto the scene. In Tales from Moomin Valley she takes in a little girl so badly abused that she has become invisible. Moominmamma, with the help of her grandmother’s old book of Household Remedies, gradually cures her. In Moominpappa At Sea (1965) she also manages to overcome the hysteria and confusion of a former lighthouse keeper who has had what seems like a nervous breakdown, and is described as “not a human being at all…more like a plant or a shadow….”

Advertisement

Moominpappa, on the other hand, is a somewhat ambiguous figure. Though an excellent craftsman, he is often dreamy and self-preoccupied. He has a continual need to feel important, to be recognized by the world, and to think of himself as in charge. This leads him first to write his memoirs—published as The Exploits of Moominpappa (1952)—and later to insist that the whole family leave Moominvalley and go to live on a small island far out in the ocean.

The story of this move is recounted in one of Tove Jansson’s best and most perceptive books, Moominpappa at Sea. (The original Swedish title does not have the double connotation of the English one, but it is certainly apt.) The story begins one afternoon, when

Moominpappa was walking about in his garden feeling at a loss. He had no idea what to do with himself, because it seemed everything there was to be done had already been done or was being done by somebody else.

He does not enjoy or even practice his hobbies any longer. As Tove Jansson puts it,

Moominpappa…had got his fishing-rod on his birthday a couple of years before and it was a very fine one. But sometimes it stood in its corner in a slightly unpleasant way, as though reminding him that it was for catching fish.

Moominpappa, like many suburban fathers with a rather meaningless job or none at all, is bored and depressed. He consoles himself by going into the garden and looking at his family reflected in a mirrored ball, which

made them all seem incredibly small,…and all their movements seem forlorn and aimless.

Moominpappa liked this. It was his evening game. It made him feel that they all needed protection, that they were at the bottom of a deep sea that only he knew about.

Moominmamma philosophically accepts the move to the island. “Now the proper thing to do was that they should begin an entirely new life, and that Moominpappa should provide everything they needed, look after them and protect them,” she thinks. In fact, once the family reaches the island and moves into a deserted lighthouse, it is still Moominmamma who looks after everyone and solves the problems that come up, though Moominpappa does catch some—indeed, far too many—fish.

Living on the island is difficult, especially as the weather turns colder. Moominpappa becomes bewildered and confused, even paranoid. Moominmamma does her best, but sometimes she has to retreat into the garden she has painted on the walls of the lighthouse. The book ends happily, but it is reassuring to learn that eventually the family will return to Moominvalley.

One of Tove Jansson’s most remarkable creations is her gallery of strange and eccentric characters, many of whom, in spite of their odd appearance, are familiar human types. The strangest species in Moominland is the Hattifatteners—mobs of pale, anonymous beings who resemble white asparagus with rudimentary arms and hands. They cannot hear or speak to Moomintroll and his friends, and are “interested only in travelling onwards, as far as possible.” The Hattifatteners irresistibly suggest mobs of packaged foreign tourists, and at one point when Moominpappa is feeling particularly restless and dissatisfied at home, he goes on a voyage with them. He discovers that “they didn’t feel, they didn’t think—they could only seek.”

The Hemulen, on the other hand, represent established authority, organization, the adult world. They look like larger, more rectangular Moomins in human dress (all Hemulen, including the males, wear long skirts). They are officials, policemen, park keepers, managers of institutions. Some are oppressive and hateful, others merely irritating or pathetic. A Hemulen in Moominvalley in November

spent the whole day arranging, organizing and directing things from morning till night. All around him there were people living slipshod and aimless lives, wherever he looked there was something to be put to rights.

Nevertheless he is tired and bored, and feels “that days passed without anything of importance happening.” Other Hemulen do not try to organize anyone but are obsessed with collecting butterflies or stamps, and none of them is any help about the house or in times of trouble.

Fillyjonks also seem to represent adult authority, but of a less oppressive kind. Most of them are female, just as most Hemulen are male. Fillyjonks, who rather resemble grey-hounds, tend to be silly and fussy, to fear dirt and insects. They are house-proud, attached to their possessions and constantly cleaning. They rigidly observe the rules of polite behavior, and often invite relatives and neighbors they dislike to meals. But sometimes, at these depressing social events, the mask slips.

“We are so small and insignificant,” [one Fillyjonk suddenly says to a guest] “and so are our teacakes and carpets,…and still they’re so important, but always they’re threatened by mercilessness….

“Tornadoes, whirlwinds, sandstorms….Flood waves that carry houses away….But most of all I’m talking about myself and my fears, even if I know that’s not done. I know everything will turn out badly. I think about that all the time.”

There are also many characters in Moominland who do not represent a species. There is, for instance, the Muskrat, who upon his first appearance announces that he is a philosopher. (An illustration shows that he has recently been reading Spengler.) The Muskrat spends most of his time in a hammock, waiting for other people (usually Moominmamma) to bring him lunch. “It’s all a matter of thinking,” he says. “I sit and think about how unnecessary everything is.” When the Muskrat absent-mindedly sits on Moomintroll’s birthday cake, he is unaware of it. “I don’t bother myself over things like cakes,” he says. “I don’t see them, taste them, or feel them in any way, ever.” The accompanying illustration, however, shows the Muskrat consuming a large piece of squashed cake.

One of the most remarkable things about Tove Jansson is her ability to feel sympathy for these rather unlikable characters. In Moominvalley in November (1971), the last and most complex of the series, a Hemulen and a Fillyjonk move into the Moomin family’s deserted house while they are away on the island. The Hemulen tries to play the part of Moominpappa, with limited success, especially when he insists on teaching everyone to ski. The Fillyjonk, who doesn’t really like children, attempts to replace Moominmamma. Though Jansson makes fun of the Hemulen and the Fillyjonk, she also pities them and even seems to respect their clumsy efforts.

By the end of the series, Jansson has got to the point where she can sympathize even with her most difficult and frightening creation. This is the Groke, a strange large dark longhaired mound-shaped creature with huge staring eyes, who seems to represent depression and despair. The Groke is a kind of walking manifestation of Scandinavian Gloom; everything she touches dies, and the ground freezes wherever she sits. If she stays in one place for an hour the earth becomes permanently barren. “You felt that she was terribly evil and would wait for ever,” Jansson says in one of the earlier books.

But even the normally self-centered Sniff can sympathize with the Groke: “Think how lonely the Groke is because nobody likes her, and she hates everybody,” he says. At first, the best anyone can do is get rid of her temporarily. But finally, in Moominpappa at Sea, it is Moomintroll himself who tames the Groke. He comes with a lantern every night to the beach where she sits freezing the sand and making “a thin sound, something like humming and whistling together,…after a while Moomintroll felt that it was inside his head.” Then he sees the Groke dance, swaying “slowly and heavily from side to side, waving her skirts up and down until they looked like dry, wrinkled bat’s wings.” When she leaves afterward, the sand where she has sat is no longer frozen. Perhaps Tove Jansson is suggesting that we must become familiar with our darkest moods, and allow them to express themselves.

A final and very interesting Moominland character is Snufkin, one of the most human-looking figures in the books. He is a solitary fellow with an old green hat and a mouth organ who seems to represent the artist—perhaps Tove Jansson herself. Snufkin is Moomintroll’s best friend, but he is not always around. He goes south in the winter, and sometimes he prefers to be alone and think of tunes.

On his first appearance Snufkin is an anonymous wanderer; later on he (like Tove Jansson) has become famous. In one story, “The Spring Tune,” his creative efforts are disrupted by the arrival of a fan, a small fuzzy wide-eyed creature called, perhaps not accidentally, “the creep.” “Just think of it,” the creep says, “I’ll be the creep who has sat by Snufkin’s campfire. I’ll never forget that.”

When Snufkin, becoming impatient with this adulation, remarks, “You can’t ever be really free if you admire somebody too much,” the creep does not hear him.

“I know you know everything,” the little creep prattled on, edging closer still. “I know you’ve seen everything. You’re right in everything you say, and I’ll always try to become as free as you are.”

In the last story of the series Snufkin, who has been searching for a new tune, is lying in his tent trying to fall asleep. But he cannot stop thinking about the other characters in the book.

Whatever he did, there they all were in his tent, all the time, the Hemulen’s immobile eyes, and Fillyjonk lying weeping on her bed, and Toft who just kept quiet and stared at the ground and old Grandpa Grumble…they were everywhere, right inside his head.

Some authors cannot forget their characters even after a book is finished. Perhaps this is how Tove Jansson came to feel in the years when she tried to turn to adult fiction, but found herself instead writing her two final, brilliant Moominland tales.

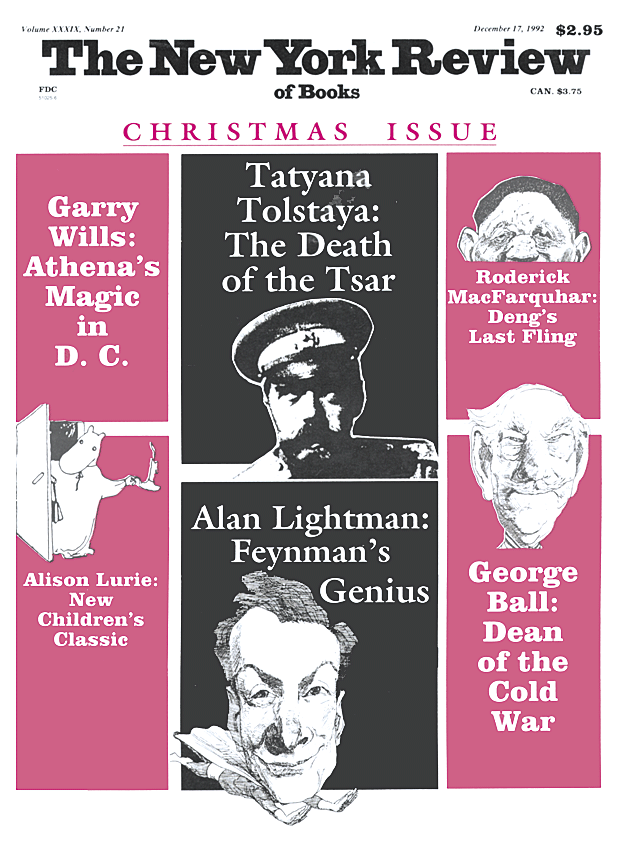

This Issue

December 17, 1992