David Margolick’s Undue Influence deals with the struggle to dispossess Seward Johnson’s widow as heir to the enormous entirety of his estate. It leaves Barbara Piasecka Johnson just where she was when she debarked to a New York pier twenty-two years before: “completely and utterly alone.” The $200 she had carried here from Poland had, of course, swelled to $240 million in the interim, but that distinction does not seem, on Margolick’s telling, to have made much difference. In the fairy tales little girls read, the heroine begins in solitude and ends living happily ever after; in the fairy tales women live, the heroine begins and has a way of ending in solitude.

Barbara Piasecka’s destiny would have been altogether less majestic but probably more serene if she had been a better cook. Mrs. Seward Johnson, Sr., had first employed her at the skillet with results so unsatisfactory as to make her preferable as upstairs maid. There she caught the eye of Seward Johnson, Sr., whose millions from Johnson & Johnson had gone on multiplying long after he had stopped pretending to executive duties in their accumulation. In time he and Barbara were married; and the displaced Mrs. Johnson seems to have felt well rid of him.

He seems to have been a dreadful old bear and so worthless a father for his six adult children as almost to excuse how pathetically short of being worthwhile they mostly were. He and his Barbara had twelve years together. For all her excesses as bully and profligate, she appears to have brought more savor to life than he had lately known; and Margolick fairly persuades us that theirs was a love story, however odd. If it hadn’t been, how could a woman as inherently shrewd as she have been so lost, so wild, and so foolish as she became after he died?

From the very outset, Seward Johnson, Sr., had doted on this wife; and as he declined toward eighty-seven, all his commands were her wishes. His will left her his whole estate with nothing for the children except the reminder that he had already made them rich with trusts. The children had been wounded by his neglect, and some were goaded by the sort of husbands the rich too often marry and then disappoint for being not so rich as expected. They sued to void their dead father’s will with the charge that, by scheming and hectoring, Barbara Johnson had forced her husband to yield her his fortune when he was too old and ill to know what he was doing.

That suit is Margolick’s stage; but his theme is civil justice, and its leading players are not the contending parties but lawyers whose rapacity perhaps exceeded Barbara Johnson’s and even her stepchildren. For this author the real case is Sullivan & Cromwell for Mrs. Johnson vs. Milbank, Tweed for the other Johnsons. Milbank, Tweed’s clients had started out on ground so swampy that Sullivan & Cromwell took victory for granted. But guile and even a measure of sincere passion all lay with the underdog; and, however well-cushioned its resolution was for Barbara Johnson, the trial turned out to be a personal disaster for her because, in Margolick’s final assessment, Sullivan & Cromwell was “overpriced, cocky, complacent” and Milbank “scrappy, industrious, committed.” Milbank, Tweed also had the luck of drawing as surrogate judge the egregious Marie Lambert, in whom nature and the coarsenings of experience had united to develop an implacable meanness of spirit. She had so little regard for subtlety in tipping the balance of equities that she fairly sprawled herself on the side of the scales against the widow Johnson, to whom she regularly referred in chambers and at lunch as “that tomato.”

Barbara Johnson’s claim to virtually all of her husband’s estate rested on a succession of wills long antecedent to the final one in dispute. Her fortune thus sat substantially beyond assault, but her fair name could be ruined, and Surrogate Lambert fell upon it with passionate will, licensed every slander Milbank, Tweed thought to mount, and finished the job with considerable success.

Margolick has applied to Undue Influence an eye precise when it engages the complexities of the litigation and wonderfully shrewd when it looks upon those of the parties to it; and he is so modestly unobtrusive about calling attention to that second and higher talent that his readers may be well along in his book before recognizing the double-edged significance of his title. This process began with the complaint that Barbara Johnson had employed undue influence to contrive her husband’s will; and its resolution was thereafter warped by the undue influence upon Marie Lambert by her own bigotries and the flatteries of Milbank, Tweed. The privacy of her in-chamber conferences with opposing counsel so far allowed her to cast off every pretense to objectivity that in one she gave full vent to her suspicions that the lawyer who had drafted Seward Johnson’s last will “was a crook and a thief.”

Advertisement

She muffled her prejudices more carefully in the jury’s presence; but all the same they clanged loudly with hectorings of Mrs. Johnson’s witnesses and coddlings of her stepchildren’s, in soft tolerance for Milbank’s Edward Reilly and harsh rebukes for Sullivan & Cromwell’s Donald Christ. Every imputation of Mrs. Johnson’s excesses passed with full license in her court; and every suggestion of worse ones in the Johnson children was barred. Marie Lambert was a spiteful and pitiless judge; and the wound she did to Margolick’s ears has expelled all pity from his account of her iniquities.

It would be fun to take this history as ground for the inference that every Cinderella must have her cruel stepmother, whether or not they meet before or after her triumph of the prince. In this instance, however, the true point seems to be that Marie Lambert was not so much a cruel stepmother as herself a Cinderella cankered with jealousy for another Cinderella who has done even better than she. Judge Lambert had spent her life in the dingier purlieus of personal injury law before she ran for surrogate; and her ambition to rise thus far above her origins had been snobbishly obtruded by paladins of the probate bar like Milbank, Tweed’s Alexander Forger. Still, she made her way by guile and cunning to presiding judge over will contests, with stakes larger than the sum total of all the personal injury claims she had ever pressed. Then she had, in Margolick’s words, “all the Forgers of the world where she wanted them…on their knees, groveling, or, as she put it, ‘kissing my ass.”‘

As ought not to have happened to the original Cinderella but probably did, Marie Lambert’s courtiers had only to prostrate themselves before her to get whatever they asked; and she faithfully did unto Barbara Johnson what fit her own prejudices and suited Alexander Forger’s pleasures.

You cannot hang around courtrooms long without being now and then distressed by the behavior of lawyers; but Margolick makes the conduct of distinguished counsel on both sides in this instance sound so excessively dreadful as to make a mystery of their motives. Why, one finally asks, were the widow Johnson’s lawyers so languid in defending and their opponents so savage in defaming her?

Sullivan & Cromwell ill-served the widow Johnson and Milbank, Tweed served her with spites outsized even for the adversary style and, in the end neither firm cared about serving any party except itself. When Philip Larkin observed, “They fuck you up, your mum and dad,” the sensible among us are disposed to respond, “We fuck ourselves up, thee and me.” All the same we cannot acquit Seward Johnson of some part in the nature of children as unworthy of respect as those that bonded together as never before in pursuit of an action at law. They were overage for waifs and so numbed by years of being too richly endowed and too meagerly loved that their cause blazed with fires only in two or three husbands who had married to score a few millions, and were now inflamed by envy of a wife who had married and scored so many more. Milbank, Tweed might sometimes pity clients like that but it could never respect them; and the embarrassments of its disdain for its own side may have made almost honest the venom of its insistence that on her side the widow Johnson was even worse than her stepchildren.

She was not of course; and yet, by Margolick’s account, the Sullivan & Cromwell lawyers commissioned to uphold her claim eventually thought her as bad a case as Milbank, Tweed and Marie Lambert ever did. She was, to be sure, wayward near the limit beyond which madness waits; and her bearing evoked all that Balzac could have meant when he said, “Show a Pole a precipice and he will jump off it.” But nonetheless, if Barbara Piasecka Johnson was undisguisably possessed by the hungers that devour fortunes, nothing about her suggested the calculations requisite for hunting after them. The high gods, as Conrad put it in another connection, could be conceived as talking about such a creature among themselves, in her particular case with amusement but not without considerable regard. To be as susceptible as Seward Johnson to the charms of any such life force pouring forth in torrents among the trickles all around him, you would need to be as old as he was when first she burst upon his eyes. Her lawyers chose instead to think of her simply as the woman who paid their fees and made earning them a torment by insisting on her own rectitude and being undissuadable from her suspicions of everybody else’s. But lawyers cannot fairly be asked to permit themselves to be distracted into the poetry and empathy that reside in the imagination; the paths the novelist must take are just the ones that learned counsel must avoid.

Advertisement

Margolick has a mind too subtle to incline to the crudities of isolating especially conspicuous villains; but, if it weren’t, its spleen would most appropriately lodge upon Milbank, Tweed’s Forger, an eminence whose zeal was admired for its bent for works pro bono everywhere else and was here employed on trucklings to Judge Lambert and frenzied contumelies upon the widow Johnson. Forger’s greed for a great fee had some excuse in the exigent circumstance of the cash flow for law firms of Milbank, Tweed’s grandeur these days; but even so his reward for this self-abasement was inadequate to his need; and, as Margolick notes, “as the economy soured, Milbank [would all too soon fire] dozens of lawyers, including many partners, with Forger the man handing out the pink slips.”

By the time the jury was ready to deliberate, Sullivan & Cromwell despaired of winning the verdict and Milbank was alarmed about losing the appeal. It was time for a settlement and the lawyers arrived at it in harmony: $6 million for each of the children and $10 million for each of the law firms, all charged to Barbara Johnson, whose total legal bill was $25 million.

The largest of her extravagances was the bitterest; and suing lawyers became her distraction, as building mansions and collecting Old Masters used to be. But her naturalization was now complete; she had been made a fully fledged, not to mention partially plucked, citizen of an America that affords every luxury, and none so expensive as lawyers.

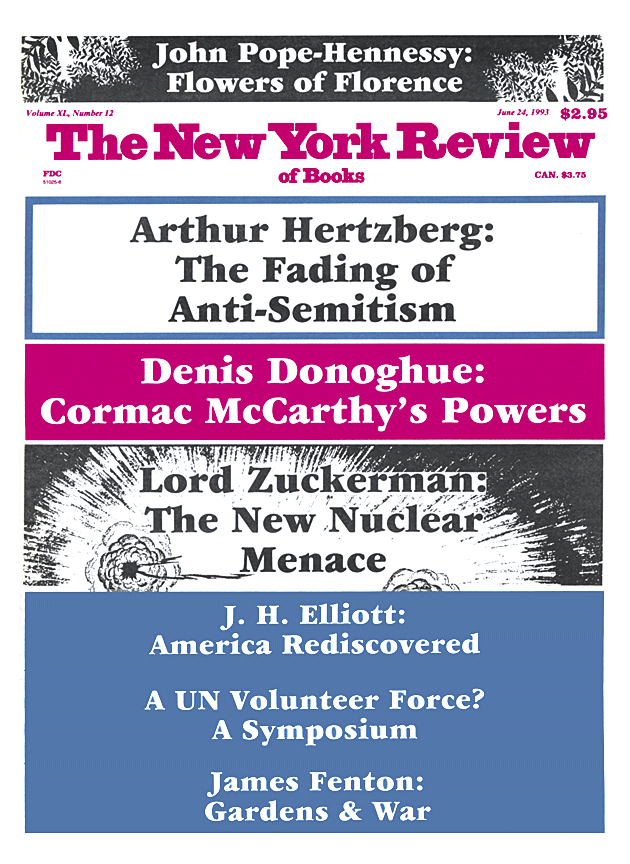

This Issue

June 24, 1993