Every major culture known to us has honored persons held to be sacred. Some of these people are wonder-workers, who have supernatural powers—seers and sacred healers. Some have liberating exemptions—they seem less dependent on their bodies or on physical comfort than the rest of us are. The most spectacular exemption is demonstrated by martyrs—they escape the need to live. This awes those less willing to sacrifice themselves for some value beyond life itself. William James observed the phenomenon:

No matter what a man’s frailties otherwise may be, if he be willing to risk death, and still more if he suffer it heroically, in the service he has chosen, the fact consecrates him forever. Inferior to ourselves in this way or that, if yet we cling to life, and he is able “to fling it away like a flower,” as caring nothing for it, we account him in the deepest way our born superior. Each of us in his own person feels that a high-hearted indifference to life would expiate all his shortcomings.1

Not even martyrdom is enough of itself to make the slain hero a leader. Some martyrs were not leaders before they died for their beliefs. Their posthumous influence does not create followership, though admiration may cause emulation. Other people may lead lives that are slow martyrdoms—“witnessings,” as the word means in Greek—by devotion to a cause beyond most worldly cares. They; too, are not necessarily leaders. The Catholic church may canonize reclusive saints, giving them an influence on the believers who pray to them. But the cultist who wears a hairshirt in honor of Saint Thomas More is, in terms of mere psychological mechanics, like the fan who refuses to wear an undershirt because Clark Gable wore none in the movie It Happened One Night. Some saints can be “holy” without having any earthly influence recognized outside the circle of such admirers. As William James said of Teresa of Avila:

In the main her idea of religion seems to have been that of an endless amatory flirtation—if one may say so without irreverence—between the devotee and the deity; and apart from helping younger nuns to go in this direction by the inspiration of her example and instruction, there is absolutely no human use in her, or sign of any general human interest.2

This is what many people think of as “the saint,” holy perhaps, as idiots are in some cultures, but of little use as a leader in the rougher world of human needs.

Yet there are other saints who do earthly work as well as bear heavenly witness. They usually put the heavenly witness first in their own minds; but the world honors them for services performed here below. To continue quoting James:

When we are in need of assistance, we can count upon the saint lending his hand with more certainty than we can count upon any other person. 3

One does not have to be a Catholic to honor Mother Teresa for her mobilization of care and nursing and feeding operations among the poor. Ruskin called such people “working saints”—to be distinguished from the kind who “with their cloudy outlines disguise, or with their impossible virtue deaden, human response.”4

What sets the saint apart from others who perform useful services is that the saint looks beyond the service performed, toward some transcendent goal or reward. Even the godless do not equate Mother Teresa with the United Way. When the saint performs the world’s work, it is done as a donkey draws a cart, by turning his back on it. To see that this is a separate type of leadership, we have to distinguish it from mere wonder-working or good-doing in themselves. The charismatic leader, like King David, performs divine deeds—but David was not a moral saint, even to his ardent followers. The philanthropist does good, but one can doubt whether he or she is good in any superlative way. The saint, by contrast, draws followers for what he or she is as well as for what he or she does. The hint of higher possibilities in life, of a larger sphere of aspiration, is what James found in such leaders:

The world is not yet with them, so they often seem in the midst of the world’s affairs to be preposterous. Yet they are the impregnators of the world, unifiers and animators of potentialities of goodness which, but for them, would lie forever dormant.5

Such people are “outsize,” for better or worse, escaping the boundaries that hold the rest of us constrained by self-regard, convention, or fear. The protection against their challenge is to dismiss them as outstandingly crazy. Most saints met that response at some point. Dorothy Day, the founder of the Catholic Worker movement, found it in her own home, in her father’s nagging contempt for what she had become. He wrote in 1937, when his daughter was forty years old:

Advertisement

Dorothy, the oldest girl [of his five children] is the nut of the family. When she came out of the university she was a Communist. Now she’s a Catholic crusader. She owns and runs a Catholic paper and skyhooks all over the country, delivering lectures. She has one girl in a Catholic school and is separated from her husband [sic]. You’ll probably hear of her if you have any Catholic friends. She was in Miami last winter and lived out with [cousins] Clem and Kate. I wouldn’t have her around me.6

Day was hurt by her father’s rejection of her, which was unwavering from the time she joined the Socialist Party in her teens. She obviously admired her father, a dour Irish writer who worked on novels and plays but made his living as a racetrack journalist. All three of his sons followed him into journalism—as did Dorothy. His daughter was the only one for whom he expressed no pride or support.

This was not because of any noisy rebellion in the girl’s past. She was always quiet and accommodating; but from infancy she kept a certain space between herself and others. This went oddly along with a desire to observe people close up. As a child in San Francisco she used to walk strange neighborhoods, wondering what the people who lived there thought. She would go into churches, to see how people behaved there. One of her vivid early memories was of the San Francisco earthquake in 1904, when she was eight—not only of her wheeled little bed rolling about on the floor, but of an influx of strangers brought together in a community of disaster. She observed her mother, for the first time, giving clothes to those whose homes had perished in the quake.7

After the quake, her family moved from San Francisco to Chicago, where Dorothy grew up taking long walks along Lake Michigan. All her life she sought the shores of lakes and oceans, which she found conducive to meditation. Later on, she would reserve serious thinking for rides on the Staten Island ferry. At seventeen, she won a writing scholarship to the University of Illinois in Urbana, where she quickly searched out campus radicals—perhaps in part because they were the most exotic parts of the student body. She always went to “other neighborhoods” of the mind, to observe different lives, discontented with what was at hand. She was reading Dostoevsky, and thought he might be causing her discontent. “Maybe if I stayed away from books more this restlessness would pass,” she wrote to a friend. 8

Her best friend at the university was Rayna Simons, a radiant Jewish rebel who ended her short life in Moscow. When Day’s family moved to New York after her sophomore year in Urbana (1916), Dorothy went along, ready to plunge into radical journalism—not, as her father no doubt informed her, a remunerative part of the profession. As soon as she had income from the socialist publication Call, she moved out of the family house and took her own apartment. She joined the International Workers of the World and worked for the Anti-Conscription League.

Since radical journalism was underpaid, it was dependent on (and open to) cheap labor. When she moved to The Masses, edited by Max Eastman and Floyd Dell, Day was the dependable one, ready to make up the magazine when others were off making speeches. She was sometimes the editor-in-chief because she was the only editor on the premises. She learned every aspect of getting a journal out on a shoestring, a skill that would be important when she launched The Catholic Worker sixteen years later.

The magazines she worked for sent her to cover slums, strikes, and radical meetings. She interviewed Trotsky during his New York visit. She went to Washington with those opposing World War I. But her most important trip to Washington was not undertaken as a journalist, and it led to her first imprisonment. She went with a friend, Peggy Baird (Hart Crane’s best woman friend), to join suffragist demonstrations outside Woodrow Wilson’s White House. Day was not a suffragist—like Mother Jones, she thought of the vote as a reformist measure, not a radical one. But she was ready to protest the treatment of suffragists in jail. She was arrested with others. When bail was put up for them, they went out and got arrested again. On the third arrest, they were sentenced to thirty days in jail. Day went on a hunger strike with the other women thrown into the Occoquan Work House. Authorities were force-feeding the hunger strikers, afraid that some prominent women might die on their premises. On the sixth day of the strike, the fasters were put in a hospital for intravenous feeding. On the tenth day, the strikers won all their demands and were sent back to a regulation prison to finish their sentences.

Advertisement

Returned to the jail with ordinary prisoners, Day was stunned by the raw sexuality of the women. When the prisoners bathed in communal tubs on Saturday night, preparing for their Sunday visits from men, “I saw sex and felt it at its crudest and was ashamed that I should be stirred by it.”9 The debility of her fast at Occaquan had sent the twenty-year-old Day into a black depression, out of which she began to pray (she still considered this a form of weakness). Returned to the regular prison she tried to forget her “lapse” into faith.10

Back in New York, she was an uncooperative government witness against her colleagues on The Masses, which had been closed for seditious libel during the war. She acquired a new circle of friends, more literary than political, which included the writers Malcolm Cowley (soon to be Peggy Baird’s husband), Max Bodenheim, Mike Gold, Kenneth Burke, Allen Tate, Hart Crane, and—most important to her—Eugene O’Neill. Tate, a Southern Agrarian, praised life in the country—the agrarians had picked up some ideas from the Catholic “Distributist” movement in England, a movement that would later claim Day as one of its victims. But at this point, she warmed more to O’Neill the playwright—to his mysticism about the sea, to his maudlin recitals of Catholic poetry when he was drinking with Day and others in their Village hangout (Jimmy Wallace’s bar).

For months Day drank through the night, then wandered out at dawn to stop by churches that were just opening. Though she did not realize it at the time, she was absorbing O’Neill’s Catholicism, from which he was still wriggling himself free. One night, as they were drinking together, a disappointed Village lover, Louis Holladay, took a phial from his pocket and swallowed most of its contents. When he went into grotesque convulsions, O’Neill and others left, presumably not wanting to get involved in a police investigation of drug use. Day held the thrashing man in her arms till he died, then took the phial so the police would not find it, and went to tell O’Neill what had happened.11

Day had fallen in love with various men, especially those who seemed, like O’Neill, “doomed.”12 But now she became deeply infatuated with a tough-guy journalist, Lionel Moise, who had awed the young Hemingway when they both worked at the Kansas City Star. Day met him when Moise had drunk and brawled himself out of newspapers into an orderly’s job at the hospital where Day was doing wartime nursing. Drawn before to sensitive “boys,” she was swept away by Moise, ten years her senior, because “You are hard—I fell in love with you because you are hard.”13 The infatuation was recorded in Day’s only published novel, which has come in for some justified feminist criticism.14 Day even nursed Moise’s other lovers, after he had dropped her, when these women got into drug or police troubles. This led to her second imprisonment. Having pursued Moise to Chicago, Day went with a woman, a recovering drug addict in love with Moise, to a house rented by IWW union men. When Chicago police raided the place, they arrested the two women as visiting prostitutes.

This experience in jail was totally different from Day’s earlier one, which she had shared with high-minded (and middle-class) suffragists. Day was struck by the way the prostitutes protected each other from the police—another community formed in disaster, like that created by the earthquake. She was strip-searched and investigated for venereal disease, and the humiliation formed a bond with the victims of official callousness. When she ran her own “hospitality houses” later, she made no demands on those who came for food or shelter.

Earlier, while she was still in New York with Moise, she had told him she was pregnant, and he ordered her to get an abortion. She did; but when she returned from it, he had left her. Suffering from her rejection, she married on the rebound a rich suitor and went abroad with him, where she spent most of a year in Sicily writing a novel about her affair with Moise (The Eleventh Virgin). Some have treated Day’s later contrition over her early life as a saintly exaggeration of remorse. They think she felt guilty mainly for sexual affairs; but she realized that the one truly disgraceful act of her life was having legal sex, with her own husband. She used the man she married, and she clearly had the spiritual discernment to see that such exploitation of others deserves remorse.15

She had left her husband by the time she returned to America in 1921 (they were divorced a few years later). She continued her work as a journalist—for the Liberator in Chicago, then the Item in New Orleans (where she wrote a series on taxi dancers after becoming one). With money derived from the sale of the movie rights to her novel, she bought a cottage on the beach of Staten Island, where she lived with her new lover, Forster Batterham (Kenneth Burke’s brother-in-law), by whom she had a daughter, Tamar. Batterham, a marine biologist who loved the sea, shared many of Day’s tastes, but was tone-deaf to religion. Their time by the sea was happy, despite her nagging sense of needing something beyond the beauty of the moment. The same emotions, stirred by the waves, that nurtured her love for Batterham were driving her away from him, toward faith. She recalled their life together as her peak of worldly content:

Sometimes he went out to dig bait if there were a low tide and the moon was up. He stayed out late on the pier fishing, and came in smelling of seaweed and salt air; getting into bed, cold with the chill November air, he held me close to him in silence…I loved him for the odds and ends I had to fish out of his sweater pockets and for the sand and shells he brought in with his fishing. I loved his lean cold body as he got into bed smelling of the sea, and I loved his integrity and stubborn pride.16

William James describes conversion as the breaking-in on the conscious mind of connections long growing in the subconscious.17 The crisis for Day was the birth of her child, the sense of responsibility for another’s soul that this brought home to her. She wanted Tamar baptized. It was done, in July of 1927. But Day could not be baptized herself, the priests told her, unless she either married Batterham or left him. Batterham was opposed in principle to marriage. She had to leave. She was baptized, five months after her daughter.

In order to support herself and her child, Day began writing for Catholic periodicals, principally Commonweal, and wrote a play on which the Pathé Motion Picture Company took an option. After frustrating months as a dialogue writer in Hollywood, she spent seven months in Mexico, writing on workers’ conditions for Commonweal. Back in New York, she lived by freelance writing and secretarial work for Catholic organizations. Her social conscience was still active, so she went to Washington with the Hunger Strikers March that picketed President Hoover’s White House. She noticed once more the absence of any Catholic leaders in the march, and went alone to pray at the Catholic Shrine in Washington. Day had not been able to put together her social concerns and her new faith. She seemed to have reached a dead end, sundered from her radical friends, unimportant to the Catholic community she had joined. She prayed desperately for guidance.

When she returned to her New York apartment, the answer to her prayers, a quietly forceful bum, was sitting at the kitchen table lecturing her sister-in-law. Peter Maurin, an autodidact obsessed with ideas, had led a vagabond life since his birth in France in 1877. He lived as a teacher and laborer, haunting churches and libraries, haranguing anyone he met.18 The whole country would become briefly infatuated with Maurin’s secular equivalent, the “teamster philosopher” Eric Hoffer, in the 1950s. But Maurin filled a permanent need for Dorothy Day from the time they met in 1932.

If their encounter had occurred in the Middle Ages, Giotto might have painted it as another meeting of Saint Francis of Assisi with Saint Clare. Only this Clare outshone her Francis: Day was more vivid and commanding than Maurin—though without Maurin, her great work would never have been launched. Day, as a convert, had no standing, not even in her own eyes, with the cautious officialdom of her church. Priests assured her that the way things are is the way they always were and had to be. Maurin knew better. Formed in a lay French tradition, he had read and pondered Catholic theology and philosophy for decades—he could supply Day with apt quotes from Saint Thomas or the papal encyclicals—but he also believed that the gospel was not being preached to the poor because church officials showed so little love for them.

It took a while for Day to realize what Maurin meant for her. Most people thought him a bore, and so did she at first. She tried to get rid of him, but he never took a hint, or even a rebuke; he just kept talking. He put his truths in maxim form, breaking up his sentences into didactically recitable breath-units. Day would later print them stichically in The Catholic Worker as “Easy Essays”—not a title Maurin liked. He thought them hard and deep.

Maurin was old enough to be Day’s father (he looked older than the twenty years that separated them), and in the deepest sense he became the only father she ever had, her “father in the faith.” He had something to pass on to her. She could rebel against this father, more than against her biological one—but the breaks were brief and soon healed.

The first fight occurred over their first project together, their newspaper. Maurin believed that the Christian gospel called urgently for three things—intellectual renewal through a worker’s publication, houses of Christian “hospitality” (he rejected the condescending term “charity” for performing a duty to the poor), and a return to life on the land.

This last point meant little to Day at the outset—though she liked to read and write by the seashore, she was basically an urban person. Farms would later plague her life, Maurin’s evil gift to her. But the first two items on his list appealed to her instantly. She would feed and clothe the poor, and her work on “little papers” of the left had prepared her to put out a Catholic publication. She did not, yet, have the money to buy food or shelter for others, but she could start a paper with only the cost of the first issue—something kept to a minimum by use of the press at the Paulist fathers’ house where she had once worked.

Despite the enthusiasm Day and her friends poured into the newspaper, Maurin grew morose as the dummy took shape on her kitchen table. Too much secular protest, he thought (too many ideas not his own): “Everybody’s paper is nobody’s paper.” He disappeared from the house. At last, when she no longer wanted to, Day had found a way to get rid of him. On May 1, 1933, in the depth of the Depression, Day and three others went to Union Square, thronged with Communists celebrating May Day, to distribute (for a penny a copy) The Catholic Worker.

Maurin returned, after the paper had appeared, and insisted that his name be taken off the list of editors. He would be responsible only for articles he wrote and signed himself. He thought the paper “too political.” His own form of personalism maintained that worldly institutions could be undermined by the power of love—they should not be confronted on their own terms. Maurin opposed labor organizations if they resorted to intimidation. “Strikes do not strike me,” he would intone (he often mistook a pun for an argument).

Day held firm in this conflict. She was not going to renounce the radical activities she had seen as vehicles of love, not departures from it. But the two were united on the need for hospitality houses, which they soon opened in Mott Street in Little Italy and in Harlem. And after they had the money to purchase a farm, Day yielded to Maurin’s insistence that a “green revolution” was the proper Christian response to industrial oppression. Maurin’s farm ideals were a mixture of Peter Kropotkin’s back-to-the-land movement in Russia, and the Catholic “distributism” invoked by Southern Agrarians like Tate.

The paper proved to be a good fundraiser for the hospitality houses, shelters made especially important by the Depression. Day touched a need in Catholics that was not filled by official church “charities”—to go out to the poor, live with them, share their lot. Those who could not do this in person sent their money. Soon the New York houses were feeding hundreds of people out of work; then, with the purchase of more space, housing them as well. A dozen other cities set up Catholic Worker houses in imitation of the original.

The Workers lived with the poor, but kept up a daily discipline of prayer, reading, and spiritual instruction. At first, this meant listening to Maurin’s droning of his maxims. But soon sympathetic priests, professors, theologians were helping out at the soup line and then holding seminars on the role of the church in the world. The movement was watched anxiously by Catholic authorities, who gave Day a diocesan “advisor” to warn her against any doctrinal or disciplinary infractions. Yet Day stayed almost magically exempt from ecclesiastical admonishment. This was partly because she rarely took a confrontational stance with the Church (as opposed to her blithe defiance of secular authority). Catholic workers picketed and agitated when dealing with corporations or the government. With the church, they usually stuck to Maurin’s tactic of undermining through love. Day no doubt felt the convert’s lingering sense that she had come into the Church as a guest. Born Catholics are often readier to tear down any parts of the old homestead that displease them.

But the deeper reason for her remarkable exemption was the response, inside her Church and outside it, to Day’s obvious sincerity, both in her religious faith and her earthly concerns.19 This was a woman who fed the poor, not with a handout, but by handing over her life to them. Yet she was also a woman who went to mass every day, and confession weekly, and wrote as much about the spiritual life as about the condition of the poor. As a radical believer, she was a nuisance to some authorities; if they had made her a martyr, she would have been a disaster for them. So when the Catholic authorities in America favored Franco during the Spanish civil war, The Catholic Worker opposed him with impunity. In fact, at the height of the cold war, Day wrote sympathetically of Marx and Lenin as lovers of the poor, yet when dockworkers struck, Irish cops refused to arrest Catholic Worker picketers.20

It was a hard life that Catholic Workers lived, which accounts for the generally rapid turnover of volunteers. Day seemed to bear all the crises with serenity, though her journals show how tormented she was by disagreements among her associates, violence in the hospitality houses, breakdowns (human and mechanical) on the farms. The hospitality houses, since they put no conditions on acceptance of those seeking help, were always coping with drunkards, the mentally ill, the sexually predacious. Day, who treasured her books, her private time with music on the radio, found that others took her belongings, broke in on her privacy with squabbles, demanded that she hear each complaint of workers or guests in the house. Alcoholic priests, or those unhappy with their vocations, had a dreary tendency to seek her out as the solver of their problems.

The farms had been intended by Maurin as permanent family communes; but those who married began to think of the needs of their children, demanding ownership of the fields they worked. Day at last had to decree that only single people could live on the farms, which made for a transitory, unskilled population.

People came to work with her for a while, then left, taking whatever part of the experience they could use in later life. A whole generation of teachers, journalists, and social workers was formed by her—John Cogley, Michael Harrington, Robert Coles, Ed Marciniak, and others. But she felt some of their departures as defections—Harrington left the Catholic church to become a socialist, Cogley left the pacifist community to become a soldier.

Cogley was part of a great defection that occurred during World War II, young Catholic Workers joining the military despite Day’s effort to set up centers for Catholic conscientious objectors. Few heeded her call. War fever closed some hospitality houses, and shrank the numbers of those that survived.

As usual, Day survived the troubles and decline. In the 1950s, the Catholic Workers opposed nuclear arming and McCarthyism with a wave of fasts, picketings, and protests. New houses were founded across the nation, and Day traveled to them constantly, raising money for them, calling on them to make retreats and deepen their prayer life (as hers was deepening at the time).

The Sixties brought into the Worker houses a new kind of radical, one that Day found disconcerting largely for generational reasons. She had been daringly sympathetic, in her earlier years, to prostitutes and drunkards. Nearing seventy, she could not feel the same empathy with lesbians or drug users. She had been jailed often for her antinuclear demonstrations, and the lesbianism of the women’s prison disgusted her. But she fought her judgmental attitude with a saint’s resolve to love everyone. Once she went to jail with the attractive actress Judith Malina Beck (co-founder of the Living Theater). When the inmates crowded salaciously around Beck, reaching to fondle her, Day brusquely demanded of the authorities that Beck be put in her cell. Then she tortured herself with second thoughts: “I found it hard to excuse myself for my own immediate harsh reaction. It is all very well to hate the sin and love the sinner in theory, but it is hard to do in practice…. Jesus is this Jackie who is making advances [to Beck].” 21

Despite all her efforts at sympathy, she felt obliged to “stomp” (in their words) the Sixties activists living promiscuously and using drugs in the New York Catholic Worker house. She also withdrew her name from the letterhead of the activists’ Catholic Peace Fellowship. This caused a rift in the Catholic left that respected figures like Thomas Merton, the Trappist monk, and Daniel Berrigan, the Jesuit priest, labored to close.22 Day remained loving toward the leaders of the Catholic peace Fellowship, but she had never questioned her church’s stand on things like contraception, abortion, homosexuality, the celibate clergy, or the male priesthood. Her combination of theological conservatism with social radicalism had protected her from being silenced by the church.

Her views were not taken on merely tactical grounds. In fact, her journals are full of prayers to help her avoid doing things for effect, “posing,” looking for approval or acclaim. This is the paradox of saintly leaders. This kind of leader is the least accommodating to followers. The ancient prophet must deliver the message God gives him, whether it has any effect or not. There is no absolutism like that of the saints. They must please their God, not their followers—but, paradoxically, that is what draws followers. It was her spiritual intensity that made Day a mentor to several generations of people concerned with the poor. She still fills that role, since The Catholic Worker has never suspended publication, and Hospitality Houses continue to feed and clothe the needy long after her death. The Catholic Worker has been read by several generations of young Catholics in seminaries and convents, where it deepened a commitment to the poor.

It was as a living mystery that Day looked back on the world from the margins where she chose to live and work. She was called “elfin” in her Greenwich Village days, more radical than anyone in the way she asked for and gave love. Her wondering gaze was caught in an early picture by John Stier, which more than any other image suggests the continuity between her early radicalism and her later dedication.

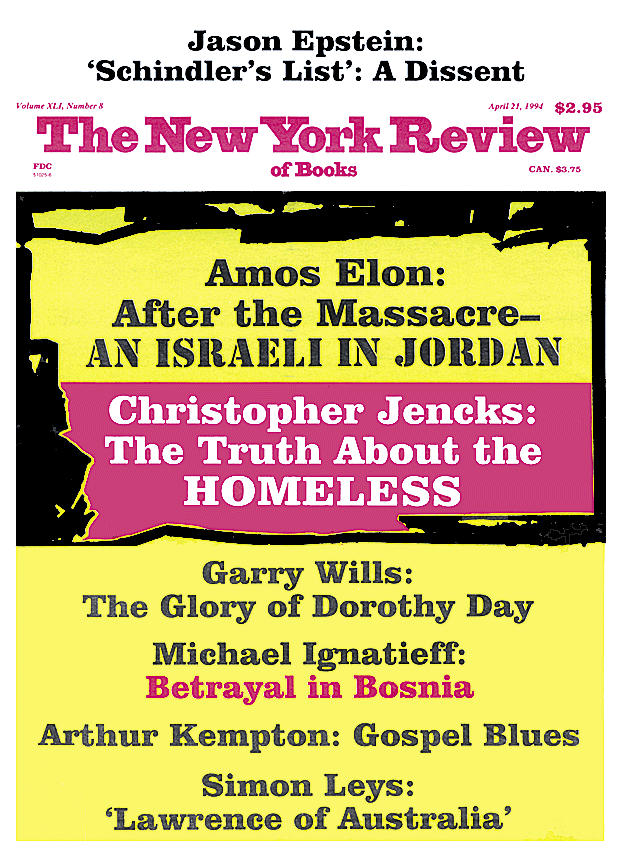

This Issue

April 21, 1994

-

1

William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902), Library of America edition (1987), p. 330. ↩

-

2

James, The Varieties of Religious Experience, p. 316. Cf. James’s description of the adolescent Jesuit saint Aloysius Gonzaga (p. 322): ↩

-

3

James, The Varieties of Religious Experience, p. 335. ↩

-

4

John Ruskin, Roadside Songs of Tuscany, in Library Edition (George Allen, 1907), Vol. 32, p. 72. ↩

-

5

James, The Varieties of Religious Experience, p. 325. ↩

-

6

William D. Miller, Dorothy Day: A Biography (Harper and Row, 1982), p. 311. ↩

-

7

Dorothy Day, The Long Loneliness (Harper & Brothers, 1952). ↩

-

8

Day, The Long Loneliness, p. 34. ↩

-

9

Day, The Long Loneliness, p. 83. The suffragists were not allowed to bathe, in those days of segregation, since black women had been in their communal tubs. ↩

-

10

Day, The Long Loneliness, p. 83: “I had seen myself too weak to stand alone, too weak to face the darkness of that punishment cell without crying out, and I was ashamed and again rejected religion.” ↩

-

11

Day never told this story in her writings, but an account of it was given by her roommate of the period, Agnes Boulton, who had been drinking with the company before Holladay’s death, and went back with Day while the body was being examined by the police (Miller, Dorothy Day, pp. 113–115). ↩

-

12

In one of her long interviews with the psychiatrist Robert Coles, Day described walking along the East River with one death-shadowed youth in a “a sort of sexual silence.” Coles, Dorothy Day (Addison-Wesley, 1987), p. 151. ↩

-

13

Miller, Dorothy Day, pp. 128–129. ↩

-

14

See June O’Connor, The Moral Vision of Dorothy Day: A Feminist Perspective (Crossroad, 1991), p. 18: “At novel’s end, June [the Day character], an adult working woman, remained a willing participant in a stirring adolescent fantasy.” Years later, in her Catholic retreat notes, Day herself wrote: “All day in a state of unrest, feeling how M. [Moise] ‘had women hypnotized.’ ” (Miller, Dorothy Day, p. 399). ↩

-

15

We have no direct evidence of the way she “weighed” her sins, since she was normally reticent about the whole period unless prodded by others or correcting accounts written by her earlier companions. Her first autobiography, From Union Square to Rome (1938), gave few details of her “godless” days. Her second, The Long Loneliness (1952), was more forthcoming, since other people’s memories of her had been published in the interval. ↩

-

16

Day, The Long Loneliness, p. 148. ↩

-

17

James, The Varieties of Religious Experience, pp. 213–218. ↩

-

18

Maurin, from a large and pious family, spent eight years as a Christian Brother and seven years in a lay activist group (Le Sillon) before leaving France for Canada, where he tried to manage a farm. After some vagrant years in America where he lapsed from his Catholicism, he began steady work as a French teacher in 1917, first in St. Louis, then in the Woodstock area of New York. He underwent a conversion experience there, and began teaching without pay, earning his food by manual labor. His teaching had turned to a continual seminar on the gospels by the time he went to New York City in the early Thirties, where be read in the public library, buttonholed people in Union Square, and haunted Catholic journalists’ offices. Cf. Marc Ellis, Peter Maurin: Prophet in the Twentieth Century (Paulist Press, 1981). ↩

-

19

Day’s work received widespread recognition outside her church after Dwight Macdonald published a sympathetic New Yorker profile of her in two parts (October 4 and 11, 1952). ↩

-

20

“Oh, far-off day of American freedom, when Karl Marx could write for the morning Tribune in New York”: Day, Loaves and Fishes (Harper and Row, 1963), p. 13. ↩

-

21

Day, Loaves and Fishes, p. 176. ↩

-

22

Miller, Dorothy Day, pp. 487–490. ↩