To the Editors:

While the world’s attention has been concentrated on the negotiations between the US and Cuba, or on the refugees waiting behind barbed wire at Guantánamo, hardly a word has been spoken about several Cuban political prisoners who have refused Castro’s offer to be released from prison if they are willing immediately to go into exile. They include Sebastián Arcos and Rodolfo González of the Cuban Committee for Human Rights, Yndamiro Restano of the Harmony Movement, Luis Alberto Pita Santos of the Association to Defend Political Rights, among others who remain imprisoned for their efforts to promote rights.

In recent months Castro’s political police have visited many dissidents and “suggested” to them that they leave the country. In fact, Castro is no longer able to export his revolution, and now would like to export the opposition. Arcos, González, Restano, Pita Santos, and others who oppose Castro’s regime inside Cuba, have renounced the use of violence. Yet the government continues to organize “rapid deployment brigades” of thugs who roam Havana and beat up dissidents with impunity.

Just a few weeks ago Castro and American diplomats negotiated a “migration” agreement. In Madrid, Cuban officials met with three exile leaders who agreed with Havana on the need to lift the US trade embargo. But unfortunately Cubans in Cuba are not allowed to meet peacefully to seek ways out of the national crisis. While the outside world concentrates on US-Cuban relations, political prisoners sleep with tiny bags—containing food, a spoon, a toothbrush or toothpaste—tied to their wrists, lest common criminals steal them. They must rely on relatives and friends to share meager rations with them. The gasoline shortages and the deterioration of the public transportation system make it extremely difficult for families to visit political prisoners who are jailed hundreds of miles from their homes. Wives and mothers are frequently strip searched. For the families of prisoners, a “successful visit” has come to mean that the prisoner has not been seriously ill and that his or her food has not been confiscated by prison guards.

When Nelson Mandela was set free in South Africa he was not sent into exile but was able to discuss peaceful alternatives to the regime that had jailed him. Writers, poets, human rights activists, and civic leaders called for his release, and signed petitions on his behalf. Men and women of good will around the world should ask Castro to release his political prisoners; those I have mentioned, and others along with them, want to stay in their country and work for a free and democratic Cuba.

Frank Calzon

Washington Representative

Freedom House

Washington, DC

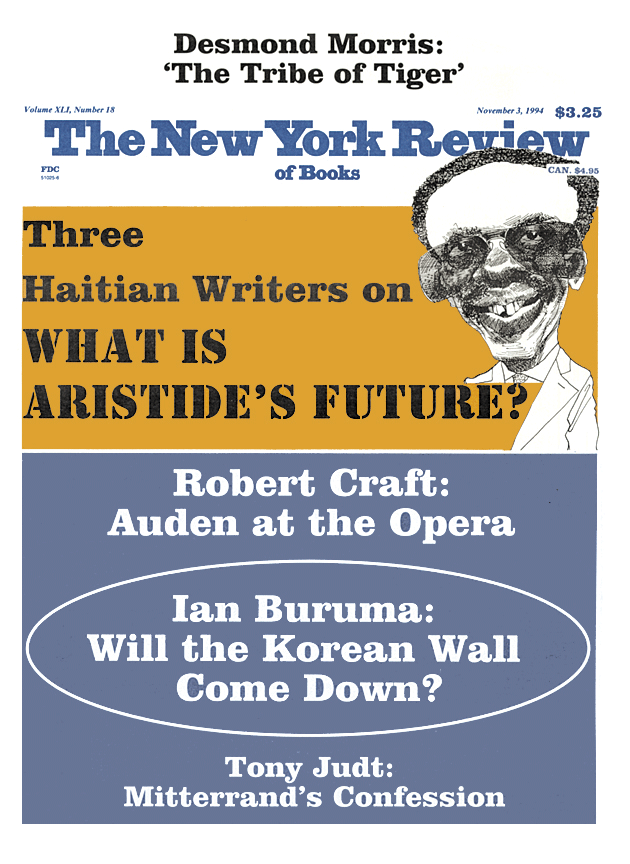

This Issue

November 3, 1994