It is a pity that Ginger Rogers’s obituaries so uniformly cast her in images inextricably tied to Fred Astaire. Of course there was the partner who was the goddess with the god, and they command our awe as unearthly creatures must. But there was also the girl who was of the earth pure and who contended with the world all by herself. And she is the Ginger Rogers who holds our heart.

The bell has tolled for the last of the great girls of boyhood’s dreams. All are gone, the Irene Dunnes, the Myrna Loys, the Jean Arthurs, the Ann Sheridans, those unforgettables in their flesh and inextinguishables in their spirit.

A departed friend who had been a Communist once told me about Ginger Rogers’s brief flirtation with and disillusionment by his former comrades. She had lent her house for a Spanish War Relief benefit and returned to find that the guests had ruined her brand-new white rugs. A few years later, she appeared before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), and, while dutifully reproaching the Communists for all manner of vague and distant sins, neglected to mention the only vivid one she knew.

She needn’t have bothered with the HUAC in the first place; but, if she had to, she would better have confined her catalog of horrors to the authenticity of her ruined rugs. She could flirt no more with illusions about revolutionaries filled with passion for the oppressed round the world but unable to consider the feelings of a woman in the house built with her toil.

The great thing about these girls was that they made it on their own and that man’s contribution was more often than not in directions of muddling them up. Heroes are generally smaller than heroines in their movies. Magnolia cannot triumph until Gaylord Ravenal gets off her back. Delightful as Irene Dunne and Cary Grant were together, his were the charms of the feckless and hers of the purposeful. Ronald Reagan did not achieve noticeable distinction as an actor until he started running for office; but, even before that historic breakthrough, he was always on call because he had a singular talent for getting out of the way and letting Ann Sheridan cook.

This dominantly feminine key governs both Kitty Foyle and Stage Door, which we may take to be the most powerful claims Ginger Rogers staked on our own hearts when she was apart from the embraces of Fred Astaire. Stage Door’s theme is sisterhood, and its men are almost supernumerary. In Kitty Foyle, Mr. Right isn’t fun and Mr. Wrong is a weakling. Kitty has to settle for Mr. Right, but her tenderness is so tinctured with resignation that it is a considerable relief to come upon Tom Dick and Harry and find Ginger Rogers free to throw her cap in the air for Mr. Doubtful Quantity.

The independent Ginger Rogers was staunchly if never sternly pure; and perhaps the Legion of Decency compelled her in that direction less forcibly than her own nature. For she who would be her own woman must learn not to take men on their face; and the comic misunderstandings that keep the Rogers-Astaire movies going between their Gershwin-Porter-Berlin summits are founded on Ginger’s almost paranoid distrust of Fred’s intentions. Only a very good girl could be quite so shrewd about life and so dumb about any man who threatens to race her blood.

And now we mourn not just her but the Hollywood that taught us to worship girls like her. Even the few bad and dangerous among them like Barbara Stanwyck were never sullen. Most of what we now get instead are belles dames sans merci and it is they and not we who are left alone and palely loitering.

The evils Glenn Close is condemned to inflict and apparently forbidden to suggest pleasure in this or any other business can only have been conceived by men who, if they do not hate women outright, cannot forgive the alimony payments for their first wives. Those divine creatures, the girls like Ginger Rogers, a bit naughty but thoroughgoingly nice, are gone from the cameras, and one more glory has passed from the Earth.

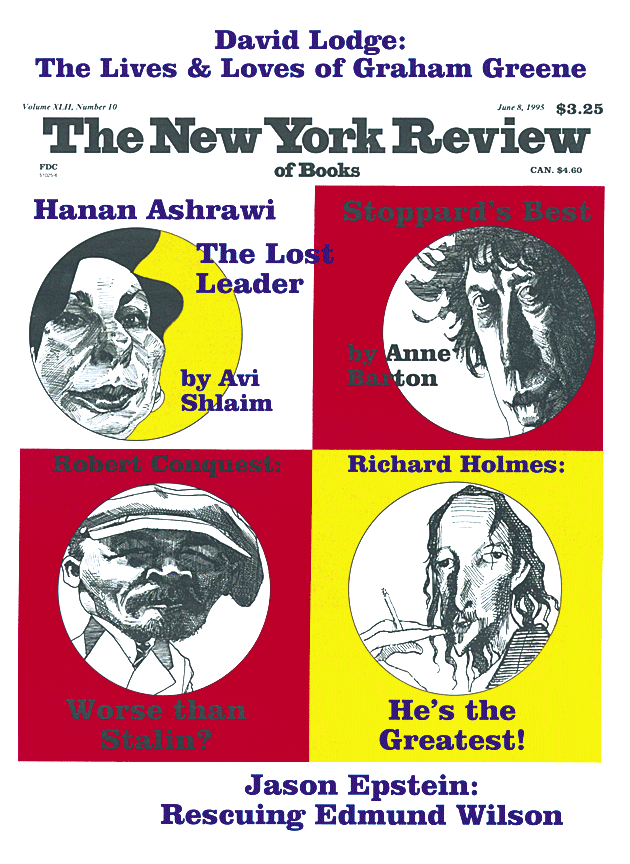

This Issue

June 8, 1995