Checking through the old Roth paperbacks, one notices how many of them make the same bid for attention: “His most erotic novel since Portnoy’s Complaint,” or “his best since Portnoy’s Complaint,” or “his best and most erotic since Portnoy’s Complaint.” These claims are understandable, as is the assumption that Roth is likely to be at his best when most “erotic,” but that word is not really adequate to the occasion. There’s no shortage of erotic fiction; what distinguishes Roth’s is its outrageousness. In a world where it is increasingly difficult to be “erotically” shocking, considerable feats of imagination are required to produce a charge of outrage adequate to his purposes. It is therefore not easy to understand why people complain and say things like “this time he’s gone over the top” by being too outrageous about women, the Japanese, the British, his friends and acquaintances, and so forth. For if nobody feels outraged the whole strategy has failed.

It seems essential to understand the seriousness of Roth’s transgressive imaginings. He is hilariously serious about life and death. In this new book life is represented as anarchic horniness on the rampage against death and its harbingers, old age and impotence. There is only one possible outcome: life can’t win against the last enemy. It can at best put on a scandalously good show. So there is really only one way for him to tell the story—defiantly, facing the outrage of death with outraged phallic energy.

D.H. Lawrence, complaining about Arnold Bennett’s “resignation” or “acceptance” in Anna of the Five Towns, said that tragedy ought to be a great kick at misery. Simply to accept misery, resign oneself to the inevitable, is merely pathetic; the kick of tragedy can convert misery into something magnificent, worthier of the living. Such is the kick delivered by Sabbath’s Theater, not only the adman’s “best” and “most erotic” but—as a reviewer might on rare occasions be allowed to say—among the most remarkable novels in recent years. With his Rabelaisian range and fluency, his deep resources of obscenity, his sense that suffering and dying can be seen as unacceptable though inevitable aberrations from some huge possible happiness, Roth is equipped for his great subject—one that was treated in their own rather different ways by the authors of Genesis and Paradise Lost.

We are disposed to think well of some novels because they have the power to make social subversion attractive. Hence the picaro of early fiction, or Defoe’s Moll Flanders, or the Smollett heroes who “take to the highway by way of a frolic,” or even Lovelace’s fatal assault on the virtue of Clarissa. They all, in their measure, provide a touch of the diabolic, in Blake’s sense. Hell is energy, the energy of the anarch is hellish. Georg Lukács called Thomas Mann’s Felix Krull a “satyr-play,” meaning that it inherits the force of its antecedent tragedies but uses it for comic subversion. Whereas Christian Budden-brook, however reckless, could not escape the bounds of middle-class propriety, Krull was, from his beginnings as a child thief, a breaker of those bounds—he has to be a confidence trickster in order to live a life appropriate to his imagination. In his impersonation of a young aristocrat, as in all his deceptions, Felix is “more ‘genuine’ ” than his original, just as Falstaff, with all his lies and all his fake pretensions to gallantry, is more “genuine” than the Machiavellian royal princes Henry and John.

That such tragicomic or satyr-play outrageousness has, in recent American fiction, taken predominantly sexual forms is largely due, as Norman Mailer remarked in his Genius and Lust, to “the irrigation Henry Miller gave to American prose.” Mailer cites Portnoy’s Complaint along with Naked Lunch, Fear of Flying, Why Are We in Vietnam?, and even Augie March as instances. They all came out of Miller’s Tropic of Cancer.1 But that book was in its early days contraband fiction, passed around in secrecy and not, like its successors, sold in every bookshop. After 1961 it was more generally, and legally, available, and it might be thought that if Miller first irrigated the prose of novelists he later did the same service to the conversation of a larger constituency. For nowadays anybody can say or write almost anything, even in prim Sunday newspapers or in what used to be called “mixed company.” And consequently the requirement of outrage becomes more difficult to meet. Yet Sabbath’s Theater meets it. It is essential to Roth’s achievement that he can startle hardened readers, make them pause to remark that they cannot remember having seen such language in print before, and to reflect that further outrage now seems close to impossible, the future charges on Roth’s imagination almost unthinkably high.

Advertisement

Sabbath is a con man and a thief, inevitably, but cheating and thieving are the least interesting of his antisocial habits, merely incidental to his principal occupation. He has dedicated himself to fucking “the way a monk devotes himself to God…. Most men have to fit fucking in around the edges of what they define as more pressing concerns…. But Sabbath had simplified his life and fit the other concerns in around fucking.” Practicing most of the perversions listed in the textbooks, he exploits women (what else, he asks, are they for?) and despises most people who assume that decent behavior is a valuable activity. He is wonderfully loquacious, and that makes him more dangerous and seductive, even as a fat old man. In certain respects he resembles the subman Moosbrugger in Musil’s Man Without Qualities, a kind of id on the loose, a threat to society. “If mankind could dream collectively,” says Musil, “it would dream Moosbrugger.” Sabbath has a Croatian mistress, whom he has trained to be joyously and insatiably promiscuous; he loves to hear of her sexual adventures and is delighted when she tells him she has had four men, not including him, in a single day. When she shows signs of conventionality and asks him to be faithful to her he is deeply shocked: “As a self-imposed challenge, repressive puritanism is fine with me, but it is Titoism, Drenka, inhuman Titoism, when it seeks to impose its norms on others by self-righteously suppressing the satanic side of sex.” But normally she is his exact female counterpart, the other half of what mankind and womankind might dream if they could dream collectively.

The immediate action of the novel takes place after Drenka’s demise, so she is an old man’s randy flashback. He continued to desire her desperately after her death from cancer, regularly masturbating on her grave: “He had learned to stand with his back to the north so that the icy wind did not blow directly on his dick.” And he observed other lovers of hers, bereaved and inconsolable, doing likewise. Some vestige of civility, hardly understandable, prevents him from insulting her bountifully cuckolded and grieving husband, whom he hates as the usurper of that title.

In the present of the book Sabbath is a battered sixty-four, still looking for the next woman, though he is dirty, ugly, and suffering a grossly enlarged prostate. As with Henry Zuckerman in the first version of his biography in The Counterlife, Sabbath’s fear of impotence is greater than his fear of death; he is fully and furiously aware that “the prick does not come with a lifetime guarantee.” Borrowing his term from a lexicon he regards as contemptibly symptomatic of the present age of schlock, he turns the tables on politically correct feminism and alludes to his “disempowered” dick.

Separated from his wife and driving from his remote place of exile in New England to New York for the funeral of an old friend, a suicide, Sabbath relives the past. He contemplates the corpse, notes its utter lack of relation to life, and feels, against what has been, or seemed to be, the natural current of his feelings, that his time has come to die. But life, the life of the con man and the seducer, is not easily reduced to resignation and acceptance. Playing the devil in the apartment of another old friend, now hatefully rich and secure, he almost succeeds in seducing the man’s wife, makes sordidly free with her daughter’s underwear, terrorizes the Hispanic maid, and steals enough money to buy himself a grave plot in the ravaged Jewish cemetery where his family is buried.

The past, as he recalls it, includes the fine time he once had as a sailor, perpetually delighted with the whores of Latin America, and later as a man of the theater turned puppeteer, using his nimble fingers, now arthritically distorted, to unbutton the blouse of a bold Barnard girl attracted to his pitch on Broadway and 116th Street. This deed gets him into trouble, avoidable but hilarious, with the police. Charged with disorderly conduct, he seems determined to achieve a conviction. “I am disorderly conduct,” he proudly tells the judge—an accurate and truly Falstaffian claim. In the old New York days Sabbath had an actress wife, long since gone missing; he seems to think it possible that he murdered her, and on occasion claims to have done so, although he also searches frantically for her, as for so much else that has gone missing.

A second wife, despised and despising, is now intoxicated with the teachings and rituals of AA, and has also become a lesbian. She has a dangerous admiration for the woman in the news who cut off the penis of her violent, but at the appropriate moment sleeping, husband. Marital discussion of that case provides some horrifyingly funny pages (this wife is a convinced opponent of circumcision). Fear of a copycat amputation was one of Sabbath’s reasons for leaving her; it might have seemed cogent to any man, but in view of Sabbath’s penile obsessions, it was especially strong for him. On the other hand, to leave her, the bread-winner, meant destitution and homelessness. For Sabbath had been fired from his job at the local college when one of his bouts of telephone sex with a woman student was taped and publicized. (The tape is here, in the true spirit of this outrageous book, transcribed in the grossest detail.)

Advertisement

A weakness of Sabbath’s is that he is not wholly incapable of love, and in these, his seemingly terminal moments, the memory of it returns to plague him. He thinks a lot about his family, and above all of his adored elder brother, killed in the war. The immeasurable loss, from which he has never wholly recovered, also destroyed the happiness of his parents. “This is human life,” says his mother, by way of comforting him. “There is a great hurt that everyone has to endure.”

He is never quite free of his family bonds; after her death his mother haunts Sabbath, even when he is with Drenka. He wears and winds his dead brother’s military-issue watch as if to do so constituted a secularized act of ritual mourning. Love of a brother, as Morris Sabbath discovers like King David before him, can “be not stranger but stronger even than the erotic.” Caught in such treacherous pieties, recalling with pain the “rich times” when the brothers caught blue-fish and were sometimes allowed to cook them, Sabbath seems drained of mockery and defiance, left with nothing but desperation. Yet, except perhaps when thinking of his brother, he is not sure that he is capable of not faking; even in what looks like an extremity of deprivation he is always, however faintly, asking himself whether he isn’t acting: “Despite the arthritis that disfigured his fingers, in his heart he was the puppeteer still, a lover and master of guile, artifice, and the unreal—this he hadn’t yet torn out of himself. When that went, he would be dead.” To be genuinely himself he needs to fake.

The energy of this book is amazing. As Sabbath remarks, “For a pure sense of being tumultuously alive, you can’t beat the nasty side of existence.” Farcically tragic invention is matched by sheer colloquial vigor. Or the mood may change: Sabbath, now easily identified as just another panhandling bum, finds himself sitting in a subway train beside a young woman who can, for a moment, play Cordelia to his Lear. Of course this lyrical episode ends badly, ends farcically, but the point is made. Such scenes have a force and originality that strike me as remarkable, as springing from some deeper source than that which supplied good, skillful books such as The Professor of Desire or the recent Operation Shylock: or perhaps any of his books since, it must be said, Portnoy’s Complaint.

Here is the aged Sabbath giving his views on adultery: “A world without adultery is unthinkable. The brutal inhumanity of those against it. Don’t you agree? The sheer fucking depravity of their views. The madness. There is no punishment too extreme for the crazy bastard who came up with the idea of fidelity.” And when he is told, by his generous but finally disgusted friend, that he is nothing but a battered relic of the Sixties, a pathetic, outmoded crank, sad, lost, isolated, he stands up unabashed for isolation, preferring it to the captivity of civilized life. Panhandling in the subway with his cardboard cup, he is again caught between truth and fake; in one sense that is where he belongs, in another he is still fooling around, faking. Finally dismissed as a “filthy sick son of a bitch,” no longer plausible as a diabolic manifestation of unlimited life, he proclaims his just and implacable hatred of the denying world.

The end of the novel is complex and beautifully sustained: There is the strong scene in the desecrated cemetery, where all noted as “beloved” on their tombstones are dead and probably beloved no longer; and the perfect narrative of an interview with a hundred-year-old man remembered from youth. As we may suppose of his author, Sabbath has a certain reverence for extreme old age, perhaps because in spite of the casualties inevitably sustained it has at least delayed the usual defeat by death, which will have to be content with a points victory. But Sabbath encounters this old man in the course of a demented search for what is left of his brother, and he steals from the old man’s house the bundle of his brother’s belongings, which include a Purple Heart and a carefully rolled Stars and Stripes. There follows a last vivid memory of that brother, of the Jersey shore—a not unfamiliar locale in Roth, but here most passionately evoked—and of childhood love. He says goodbye to the memory of Drenka (encapsulated in a candid recollection of an exceptionally perverse encounter), and even finds time to indulge in an extremely detailed fantasy of his wife masturbating.

Returning, however unwillingly, to her New England house—having nowhere else to go—he finds himself shut out, finally isolated. He makes his will, plans a last visit to Drenka’s grave. But one last unwanted encounter with the forces of decency in the shape of Drenka’s disgusted policeman son leaves him alive in spite of himself, and now full of hatred. We are at last invited to despise him, but that is a mere feint—novelists feint as well as puppeteers and con men—and instead we are left admiring the unextinguished energy of his contempt for the decent.

For all the anarchic force of its language there is nothing unruly about the structure of Sabbath’s Theater; it is hardly news that Roth is a bold and skillful architect. Like his hero, he has illusionist skills, everywhere in evidence—he is a sort of puppeteer, a virtuoso of both dissimulation and impersonation; it is well known that he likes to set himself difficult technical problems. Deception is an example, a novel entirely in dialogue, finely exploiting its self-imposed constraints, and although not in what one immediately recognizes as his palette, it gives a new coloring to certain of Roth’s obsessive interests. He is fascinated by all the different possible ways of doing narrative, as well as by the relation of the told to the teller, the problem to the solver. Roth may well believe, or wish one to believe that he believes, that writers are, or ought to be, in certain respects, quite like Sabbath; from Deception we learn that the nature of the writer is “exploration, fixation, isolation, venom, fetishism, austerity, levity, perplexity, childishness, et cetera. The nose in the seam of the undergarment—that’s the writer’s nature. Impurity….” The speaker here is condemning Lonoff, the austere, temperate, dignified author celebrated in The Ghost Writer. He is also impersonating his own author. It is almost redundant to point out that “the terrible ambiguity of the ‘I’ ” is a topic that obsesses Roth. The provisional title of a biography of the alter ego Zuckerman is Improvisations on a Self. In Roth there is no question of the disappearance of the author; he is there, sometimes even under his own name. But he is there on his own terms, in charge; he doesn’t despise Lonoff’s control of affairs.

Other themes recur, whatever the narrative finesse; one is the distinctiveness of being an American Jew, so different from being Israeli, yet also bound to a terrible past and to connoisseurship of the varieties of anti-Semitism. These preoccupations take many different narrative shapes, but the novelist’s passion for strange, new-fangled narratives is always in some respects a passion for his own narrative, his improvisations on himself. Roth often looks back over his own work and considers, in its many transformations, the terrible ambiguity of the “I.”

Sometimes he does so with that saving hilarity which can be a mask of tragedy. Sabbath’s Theater is funny, but as a means to an end; it succeeds in the task Shakespeare set his young lords in Love’s Labour’s Lost, to move wild laughter in the face of death. Possibly another laugh might come from awareness of the pretentiousness of that intention; but all the same this book is undoubtedly, in the final analysis, about matters of life and death.

Even for Sabbath life cannot be one long bout with a matching carnality, as it is for Drenka. He cannot quite exclude the other kinds of love; to do that is one of the few illusionist tricks he hasn’t mastered. In normal circumstances Roth has a crafty double supervising his tricks: so permanent a companion that he can’t easily distinguish between the true and the fake. Happiness, among other things, is always likely to be whisked away as if by an omnipotent conjurer.

In The Professor of Desire what seems like true contentment in love is shadowed by the sense that this is not what can last, not even what the happy man can make himself want to last; desertion of some sort will move in on happiness, as death on life. The trick is to use this intelligence as the propellant of a great kick at misery. If it has to be delivered by one whose opinions or improper prejudices, whose monstrous conduct, are disgusting, well, too bad. Others may make their way to the tomb measured and considerate; good for them, poor suckers, but theirs is not the only way, there is a diabolic alternative. Of course it will all end in despair, in hell, the hell of rejection by the salauds of respectability; but hell is energy, even if it has to be the energy of hatred, as if a passion for the body of a Drenka must be converted, by the action of time and disease and death, into a salutary loathing for the world that permits and institutionalizes horror—the horror of her cancer, the horror of the brother’s death at twenty-two.

King Lear, with whom Sabbath advertises a certain affinity—each, in his way, a foolish and a fond old man—rages not against his own faults but against Justice, as it is conceived by its exponents, the corrupt judge and the beadle with the lash—all covert lechers, all enemies of life, of a sexual freedom they secretly envy. It is this justice that Sabbath rages against; and so, with all his characteristic ironies and reservations, does the author of this splendidly wicked book.

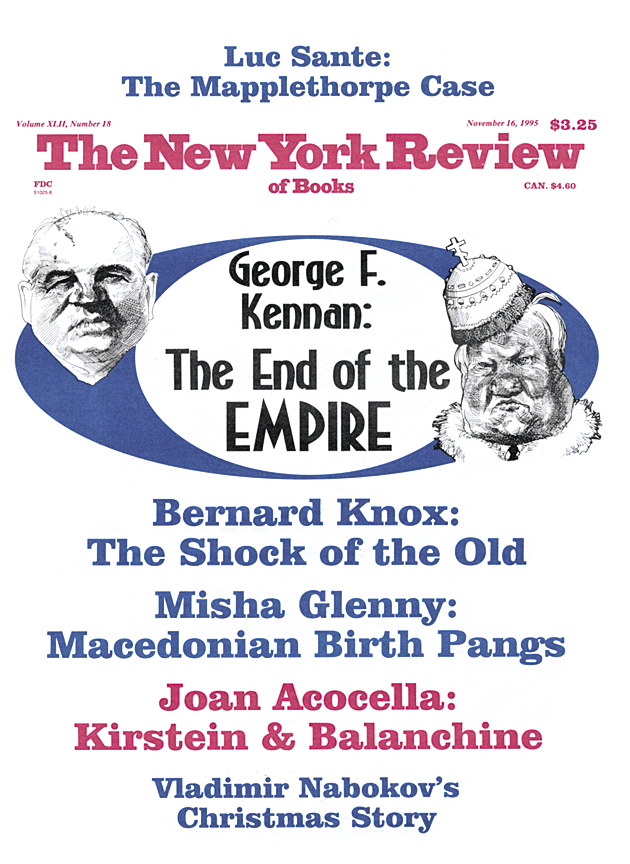

This Issue

November 16, 1995

-

*

A valuable study of the influences of The Tropic of Cancer forms the coda of Warner Berthoff’s A Literature Without Qualities: American Writing Since 1945 (University of California Press, 1979). The quotation from Mailer occurs on p. 170. ↩