During the last two decades, English and, above all, American art historians have been taking a somewhat surprising interest in German art. Fifteen years ago Michael Baxandall published his book The Limewood Sculptors of Renaissance Germany, a study of such artists as Tilman Riemenschneider and Veit Stoss, which remains the most penetrating investigation of a particularly idiosyncratic chapter of German late medieval art.1 James Marrow and, more recently, Jeffrey Hamburger have dealt with the relations between German religious imagery and German traditions of religious devotion and mysticism.2 Two years ago Christopher Wood took readers into the German forests in a remarkable book, Albrecht Altdorfer and the Origins of Landscape, and Joseph Koerner explored a similar subject in his thoughtful study Caspar David Friedrich and the Subject of Landscape of 1990. More than a few other studies of German art history have since appeared.

How can one explain this unexpected shift in taste? In the past American art historians had been predominantly interested in French and Italian art. Does German art, with its often mysterious, introverted, even tormented aspects, appeal to a curiosity about societies in turmoil characteristic of our own fin de siècle, in which many scholars have become tired of norms and perfection? Did the surprising success of such mystically inclined German artists as Joseph Beuys and Anselm Kiefer in the United States during the Eighties result from some nostalgia for the magic of Romanticism?

Joseph Koerner’s The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art may be the most ambitious of recent American reflections on the mysteries of German art. His elegantly written book deals with the fateful period in the history of German art when it reached its highest point in the works of Albrecht Dürer, the German Apelles, and then sank into deep, even self-destructive crises in the aftermath of the Reformation. The first part of the book contains a lengthy discussion of Dürer’s self-portraits, especially of the famous one in the Alte Pinakothek at Munich showing Dürer as a wonderfully handsome young man. The second part has the portentous title “The Mortification of the Image” and is largely dedicated to Dürer’s most gifted—but also his most independent—pupil and follower, the painter Hans Baldung Grien, who was mainly active in Strasbourg. Koerner, who concludes his book with a short chapter on Cranach, has evidently struggled to give it a cohesive structure, but the chapters on Dürer, Baldung, and Cranach all stand somewhat apart from one another, as if they had first been written as independent pieces and collected into a book at a later period.

The twenty-eight-year old Albrecht Dürer was already a famous artist in 1500, the year he painted his great half-length self-portrait with “proper colors,” as the inscription proudly proclaims. The painting’s high artistic quality quickly won praise, but for German humanists such as Conrad Celtis and Christoph Scheurl and the Dutch art historian Carel van Mander, it was the portrait’s astonishing resemblance to Dürer that aroused particular admiration. Even Dürer’s dog, it was said, was deceived by the painting and licked its face. This reaction, of course, was only a variation of similar legends that had long been told about the magical power of painters.

A completely different reading of the Munich self-portrait became fashionable in the nineteenth century with the Romantic veneration of Dürer as a specifically German genius. In 1809 Bettina von Armin, who readily fell into a state of rapture, wrote to Goethe from Munich:

You have appeared to me as the spiritual semblance of immortality…. Although the face of Dürer is a totally different one, the language of his character has reminded me powerfully of Yours. I have had a copy made for me…and I took refuge in this image as my household god.

Dürer and Goethe were now considered interchangeable physiognomic incarnations of Teutonic genius. But this was only a first step. After 1815 the restoration of the lost union between religion and art became one of the explicit aims of the Romantic poets and painters, and it was in this nostalgic climate that Dürer’s Munich self-portrait finally underwent what amounted to physiognomic deification.

The first trace of this apotheosis known to me dates from 1825, when a little-known conservative Bavarian politician named Max Procop von Freyberg-Eisenberg insisted on the thoroughly German character of Dürer’s facial expression. He went on to say that Dürer “even tries, in the attitude of his portrait, to approximate the image of the Saviour of the world as it exists in a certain tradition.” Freyberg-Eisenberg gives a pious explanation for this analogy between German genius and God: Dürer represents himself as similar to Christ, “to whom his whole art was dedicated.” Thus we can see that the basic argument of the first part of Koerner’s book was first made in the days of Schelling and caspar David Friedrich, at the height of German Romanticism. Since the nineteenth century the idea that in the Munich self-portrait Dürer looks like or even is Christ has been accepted by nearly every German art historian; it needed all the cool skepticism of a historian such as the late John Pope-Hennessy to look at the portrait differently.

Advertisement

Nietzsche seems to have thought of himself as Zarathustra, but in the history of art we know of no other case where a Christian artist represented himself as Christlike. No wonder that art historians, once they had decided to recognize in Dürer’s self-portrait the likeness of Christ, tried to defend Germany’s most revered artist against the suspicion of blasphemously deifying himself. Moritz Thausing, who published the first scholarly monograph on the artist in 1876, optimistically claimed that Dürer had created the modern ideal of Christ by using his own face as a model, just as Goethe had portrayed himself in Werther and Faust. Germanic genius was not to be inhibited. Koerner points out that later historians such as Erwin Panofsky sought more subtle explanations. “How,” Panofsky wrote, “could so pious and humble an artist as Dürer resort to a procedure which less religious men would have considered blasphemous?” Koerner comments that

since Panofsky, most scholarship on the panel has been devoted to defending Dürer against the charge of blasphemy. Historians have generally legitimized the Christomorphic dimension of the Munich panel by linking it to features of late medieval piety. Panofsky, for example, argued that in fashioning his portrait after Christ’s likeness, Dürer expresses the doctrine of the imitatio Christi: the belief, that is, professed by St. Francis and popularized in the North by Thomas à Kempis, that to follow Christ is to become like him, to humbly take up the cross and share in his Passion.

In this way the artist’s pious humility seemed salvaged. But Panofsky added that Dürer’s self-portrait also corresponds “to the modern concept of art as a matter of genius,” according to which the painter is “in some measure part of the creative power of God.” As a genius, Dürer was allowed to look like Christ.

In reading Koerner’s chapters on Dürer’s self-portrait, one is intrigued to observe how the author constructs an impressive scholarly apparatus—with long sequences of images and texts—yet does not end up with a conventional scholarly explanation. He always leaves open the questions he raises. For a long time, to take an example, art historians had assumed that Dürer, in his Munich portrait, might have turned to the iconographic tradition of the “Veronica,” which was one of the so-called acheiropoetoi, sacred images that were not made by human hands but were believed to be the authentic imprint of the face of Christ himself. The Veronica was a piece of cloth with which a pagan woman named Veronica allegedly wiped the sweat and blood from Christ’s face on the road to Calvary, and on which the face of the Saviour was impressed. It was venerated as a relic and often copied in late medieval art.

Dürer himself depicted the Veronica in a moving engraving of 1513, and we cannot exclude the possibility that he had the sacred image in mind when he painted himself like Christ. Traditional iconographers would probably leave it at that, but for Koerner this generally accepted hypothesis serves as a provocation for an even more daring explanation of Dürer’s entire enterprise. With shrewd persuasiveness he argues that in choosing the miraculous self-portrait of Christ as the model for his own self-portrait, Dürer enhances the “claim to the legitimacy, sanctity, and metaphysical originality of his art.” Like the acheiropoetos, the Munich self-portrait “claims to be produced ex se.” In other words, the artist reveals himself as an alter Deus, another God.

Yet Koerner’s interpretation of Dürer’s self-portrait is even more complex than this. Again and again he circles around the portrait of the godlike artist, trying to explore all its facets and, above all, the ambivalence hidden behind its flawless facade. Among the thorny problems for the interpretation of the self-portrait as Christlike is the disparity between its undeniable autoerotic narcissism and its pious humility. For a way out of this dilemma, Koerner turns to one of the most innovative theologians of the late Middle Ages, Nicholas of Cusa (1401-1464), who taught, in his De visione Dei, that while looking at the face of God as revealed by an image such as the Veronica, man is at the same time regarding God and being himself regarded by God; love of God and love of oneself are thus no longer exclusive but reciprocal. Following this line of thought, one might say that the self-love of Dürer, who represented himself as Christ, is identical to his love of God. Dürer’s autoerotic narcissism would then be just another expression of piety. In the beauty of his own person he would love God. Here Koerner is evidently playing a highly sophisticated game with Dürer’s mysterious portrait, and the reader may be tempted to wonder whether some of his arguments are too clever to be true.

Advertisement

Toward the end of Koerner’s discussion of Dürer, we are faced with a situation that recalls the last lines of Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray: “They found hanging on a wall a splendid portrait of their master…in all the wonder of his exquisite youth and beauty. Lying on the floor was a dead man…with a knife in his heart.” In 1503, a few years after the Munich self-portrait, Dürer drew himself nude in a tense pose, visibly emaciated by recent illness. This unexpected image leads to a dramatic and unexpected shift in Koerner’s argument:

Dürer evinced here a kind of narcissistic crisis, in which the celebration of his own physical beauty in the 1500 Self-Portrait gives way to an awareness of the frailty of the flesh or, more radically, in which all that had to be expelled in order to sustain the narcissistic ideal—ugliness, particularity, sexuality, and death—comes back to haunt the self as it compares its own real body against its constructed ideal.

What was repressed in the perfect self-portrait of 1500 here returns to take its revenge; the image of the “imperfect, vulnerable, mortal body” emerges much like the dead man on the floor beneath the splendid portrait in Wilde’s novel. Koerner’s Freudian analysis of Dürer’s nude self-portrait may not be to everyone’s taste, but it permits him to explore some of the darker aspects of individualism in German Renaissance art.

In his discussion of Hans Baldung Grien, Koerner believes he has discovered the artist who consciously distorted and even mocked Dürer’s idealized self-constructions. Baldung (1484/85-1545) may be called the only true intellectual among the painters of the German Renaissance. Partly for this reason he has until recently been much less popular than Altdorfer or Cranach. He spent most of his life in Strasbourg, where his father, a jurist, worked for the bishop, and where his brother Casper served as city advocate from 1521 to 1532. At a time when artists in Germany were still mostly regarded as simple craftsmen, Baldung could frequent the milieu of lawyers and humanists, and this clearly influenced his art. Classical subjects are rare in his work, but his disturbing images of love and death, of witches and their mysterious sorceries, reflect the interests and themes characteristic of the peculiar forms of humanism practiced in Strasbourg.

Little is known about Baldung’s early career. Although there is no documentary evidence that he did so, most historians assume that he spent a number of years in Dürer’s workshop in Nuremberg. There are many signs of a close connection with Dürer, especially in his early work, but this was not the usual relation between master and pupil. From the beginning Baldung’s work with its grotesque figures seemed intended to distort Dürer’s forms and models, which served him as an idealized canon to be undermined. It is this seemingly willful disfiguring of the master that attracts Koerner’s curiosity. He discovers in the relation between Dürer and Baldung something similar to a nineteenth-century conflict between father and son, and it is apparently for this reason that he puts on the title page of the second part of his book the following citation from Nietzsche’s Zarathustra: “Was der Vater schwieg, das kommt im Sohne zum Reden; und oft fand ich den Sohn als des Vaters entblösstes Geheimnis.” (“The son says what the father does not, and I often found that the son revealed the father’s secrets.”)

The chapters on Baldung, in which he has plenty of scope for his sophisticated voyeurism, seem to me the most brilliant and original part of Koerner’s book. Baldung’s interest in magic, the macabre, the pornographic, and the destructive effects of eroticism appeals in many ways to a late-twentieth-century sensibility. Koerner takes up the question of Baldung’s modern affinities with great intelligence and much imagination, dealing thoroughly with the troubling, twisted, often sinister aspects of the painter’s imagery. He has thereby given us a new view of Baldung’s art.

The theme of love and death—Eros and Thanatos—that recurs in several of Baldung’s paintings and woodcuts had longstanding medieval antecedents and lived on into nineteenth-century poetry, as in Goethe’s famous poem “Die Braut von Korinth” or in the verses of Swinburne’s “Dolores”:

Death laughs, breathing close and relentless In the nostrils and eyelids of lust,

With a pinch in his fingers of scentless And delicate dust.

In a painting like Baldung’s Death and the Woman (Kunstmuseum, Basel) from about 1518-1519, a skeleton—death—embraces and bites a seductive nude female, who seems to stand on a tomb. Traditionally minded iconographers have thought the skeleton was either a vampire or a spirit reawakening a woman who had died. But this is just the kind of learned iconographic domestication of the image that Koerner wants to challenge in calling his two main chapters on Baldung “Death and Experience” and “Death as Hermeneutic.” He writes that the painting

situates us at the moment when Eros and Thanatos merge: sex, expressed in the woman’s concealed/revealed flesh and in the corpse’s act (for its bite is also a lipless kiss), becomes identical to death, expressed in the garments as funeral shroud and in the bite as putrefaction. And all around, opening up with the woman’s clothes, the beholder’s eyes, and the jaws of Death, are yawning graves, cemetery versions of the bridal bed.

This takes us as far as a reading of the picture based on the literary tradition of love and death might go. But in Koerner’s interpretation, the disturbing message becomes clear only if one pays attention to the way the artist uses the image’s various allusions to manipulate the reactions of the person seeing the painting, the “implied beholder,” as Koerner puts it.

Nothing in this painting is quite as sensual, in the sense of strongly felt, as this meeting of opposites, where the soft, warm, and living flesh of the woman meets the hard, cold teeth of Death. Surely the corpse’s gesture is linked to the position of the picture’s implied male beholder: where he can only look, the cadaver can touch and taste. This grotesque tableau of almost fulfilled desire links sexuality to repulsion within the experience of the painting. Death is the viewer’s doppelgänger within the painted world. Nibbling at the bait, it expresses male erotic desire at the very instant it annihilates that desire.

The true meaning of the image, Koerner argues, begins to emerge only when the viewer becomes part of it. At the same time sexually aroused and fatally disillusioned, the person seeing the picture may identify with the fallen Adam, punished with expulsion from paradise. Baldung has thus radically disfigured Dürer’s idealized construction of the perfect male—Adam portrayed like Apollo. Koerner calls on Luther for help in supporting his interpretation of the picture.

Luther, too, speaks of the “bite” of death. In his Ascension sermon of 1527, he writes that “Death fastens his grip on Christ, wanting to eat for once a dainty morsel; Death opens his jaws wide and eats him up like all other people.” Elsewhere Luther prays for death not to “bite” him. And surely Luther and Baldung could not have been unaware of the close proximity in Latin between “death” (mors) and “bite” (morsus).

Not everyone will be immediately seduced by the swift connection Koerner draws here between visual and verbal metaphors. Once more the author’s argument, or part of it, may sound all too clever. But Koerner’s analysis of Baldung’s Death and the Woman remains an astonishing and illuminating performance.

Baldung’s well-known representations of witches—a painting, a woodcut, and a number of drawings—all date from the 1520s. The belief that witches practiced magic during their nightly gatherings was widespread in Germany until the seventeenth century; so were the witch hunts that were the gruesome consequence of such superstitions. Although actual witch trials seem to have been rare in Strasbourg, the city was one of the most virulent intellectual centers of this misogynistic mania. The Witches’ Hammer, a kind of handbook for the identification and persecution of witches, was published in Strasbourg in 1482. In 1508 Geiler von Kaysersberg, one of the most famous preachers of his time, delivered, in the Strasbourg cathedral, twenty-six of his forty-six Lenten sermons on witches. Baldung’s images of witches belong to this sinister local tradition.

Koerner’s discussion of Baldung’s pictures of witches follows much the same line as his analysis of Death and the Woman. He again makes much of the reaction of the putative viewer who, while regarding these disturbing images, becomes the passionate and horrified voyeur of the witches’ illicit sexual practices. In reading Koerner’s flowing descriptions of these erotic scenes, one can sometimes not help being reminded of the Sadian intermixture of cruautée and délice. “At once grotesque and erotic,” he writes, Baldung’s pictures “cause in their male viewer alternately disgust and excitement, impotence and erection, abjection and onanism.” But Koerner is of course well aware that Baldung’s images of witches, as lecherous as they may be, have nothing to do with the eighteenth-century tradition of the “philosophy of the boudoir”; they belong to a sixteenth-century world of self-reflection, confession, and sin. “Baldung’s witches,” he writes, “dedicate their sabbath to the male onlooker, disclosing within his heart the corruption they themselves parade.” The evil the beholder watches is his own. The image stands before him like his confessor, revealing and punishing his own inescapable sinfulness.

But this is not Koerner’s last word on Baldung. In a final chapter with the perhaps too-fashionable title “The Death of the Artist,” the painter himself becomes the symbol of the fallen state of man. Dürer, Baldung’s master, had used a tablet with his monogram as proof of his undisputed authorship. In a woodcut of 1519 representing the Fall, Baldung puts a similar tablet with his own initials beneath the foot of Eve,

in the place of the serpent, thus associating himself at once with the devil as original instigator of the Fall and with the continuing symptom of fallenness: carnal lust…. By transforming the artist’s monogram, proof of authorship and emblem of artistic originality, into the malevolent instigator of evil, Baldung also constructs an audacious analogy between fallenness and the originary power of the individual artistic self.

When the argument has come this far, the next step, the last twist of the plot, can only be the annihilation of the artist’s own narcissistic self—at least the self as Dürer had splendidly presented it in his own portrait of 1500. That is just what happens in the Bewitched Stable Groom, a woodcut dated 1544, one year before Baldung’s death. In Koerner’s interpretation, the “radically foreshortened figure” of the groom lying stretched out on the floor of a stable, with a horse in the background and a witch looking in the window, is Baldung’s—and German Renaissance art’s—last self-portrait:

There lies the artist himself, unthroned from his upright and godlike place as measurer and measurement of the world.

In Thomas Mann’s Doktor Faustus, Fitelberg, a Jew from Lublin living in Paris, says to Leverkühn, the German composer: “You probably do not realize, cher Maître, how German is your répugnance, which…I find characteristically made up of arrogance and a sense of inferiority….”3 Like Mann’s novel, Koerner’s discussion of the tension between the godlike self-elevation and the sinful fallen state of the artist is a commentary on the intellectual and spiritual turmoil of German art. One certainly cannot imagine a similar book being written on Venetian or Florentine art of the same period. And in a curious way Koerner himself seems deeply—or should we say narcissistically?—involved in the ambivalences of the obscure topic he has chosen for his remarkable book. It is this involvement which makes one think not only of Leverkühn but also of Thomas Mann.

Koerner’s book is difficult to argue with. It is enormously learned but it proceeds less by arguments than through the use of an evocative rhetoric and ingeniously chosen associations. Koerner himself is well aware of his own suggestive technique and illuminates it with a telling biblical metaphor:

Does not the whole character of our interpretation represent the kind of knowledge precipitated by the bite into the apple: fallen knowledge as the advent of a plethora of meanings without the authority of a meaning, and as the loss of an unequivocal and “natural” access to things and to the meaning of things?

The loss of stable meanings and established authority, and the resulting uncertainties about truth and falsehood, according to Koerner, are thus not simply the product of our postmodern and poststructuralist age, but have been with us since the Fall. Against “a plethora of meanings,” arguments are of little help. But Koerner is much too intelligent and self-conscious a writer not to see the traps in which fallen knowledge may be caught. “One sometimes wonders,” he writes, “whether what art historians discover as the implied beholder is not really a reflection of themselves transposed in the historical material.” Turning narcissism into a method of interpretation was perhaps the price he has had to pay for writing a stimulating book that offers deeper and more disturbing insights into German Renaissance art than most earlier scholarship.

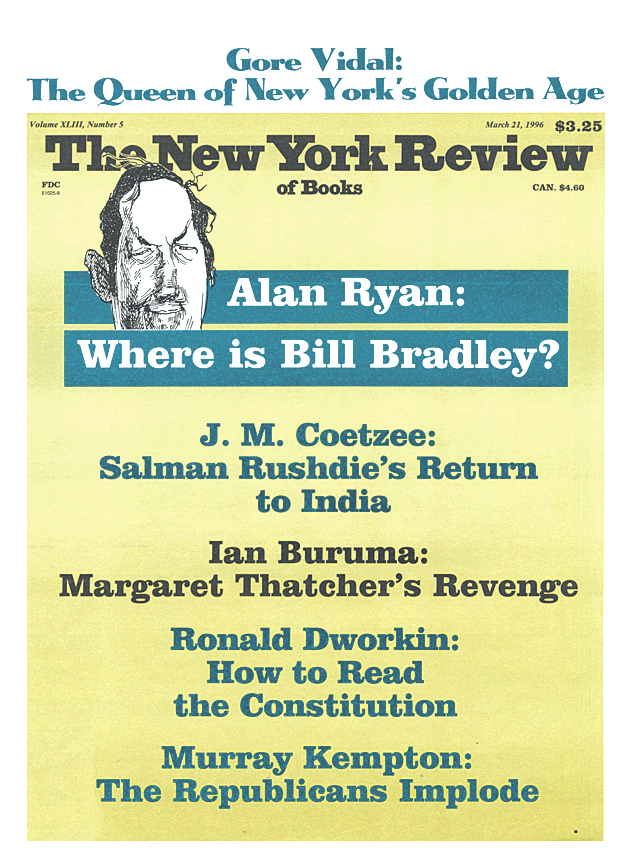

This Issue

March 21, 1996

Queen of the Golden Age

Too Nice to Win?

Palimpsest Regained

-

1

See the review by Henri Zerner, The New York Review (December 18, 1980), p. 52. ↩

-

2

James H. Marrow, Passion Iconography in Northern European Art of the Late Middle Ages and Early Renaissance (Belgium: Van Ghemmert, 1979); and Jeffrey Hamburger, The Rothschild Canticles: Art and Mysticism in Flanders and the Rhineland circa 1300 (Yale University Press, 1991). ↩

-

3

“Sie wissen wohl gar nicht, Maître, wie deutsch Ihre répugnance ist, die sich… aus Hochmut und Inferioritätsgefühlen charakteristisch zusammensetzt….” ↩