1.

Among the junk mail that arrives through our doors we find letters, sometimes impressively produced, promising to trace our name and ancestry back through the generations. We, too, can be entitled, for a fee, to claim kin with eminent or at least socially presentable ancestors; to have a pedigree drawn up and illuminated, on quality paper or indeed (why not?) on parchment, complete with the coat of arms of some long-dead person of the same name: some armigerous Griffin of yesteryear, who may impress our friends and put a snap in our walk and a sneer on our lip as we mingle in a world where, in these democratic times, we have to live on terms of apparent equality with poor fellows who have no ancestors at all. At the individual level, such attempts to gain status raise a smile. But it is a sad truth that groups, and nations, behave without shame in ways that would make their individual members blush; and the age we live in is one in which groups make such claims with great tenacity and great seriousness.

What is at stake when a group or a nation claims or is assigned descent from a past community? Very often it has been primarily a matter of glorifying one’s own group, attaching it to some prestigious name or dominant tradition from the past: thus the Romans descended from the city of Troy and the goddess Venus; the British are the Lost Tribes of Israel. It has also been a common way of fitting a foreign group, or a newly encountered people, into one’s own picture of the world and of history: Who, for instance, were the indigenous peoples of the New World, and how did they fit with the Bible and with Aristotle? In a modern mixed society it may be an assertion that one’s particular ancestors were the most important element in the mixture. At all times it has generally been true that statements apparently about the past are really claims about the present.

The early Greeks, “Hellenes” in their own language then as now, produced a simple genealogical account. They supposed that they were descended from a man called Hellen, the separate branches of the Greek people deriving from his sons and grandsons: Doros for the Dorians, Ion for the Ionians, and so on. As for Hellen’s parents, since he must have had some, they were simply declared to have been Deucalion and Pyrrha, the only couple to have survived the Flood. The claim here for the historical period is that all those who were called “Hellenes” really were related to each other, that they did form one people. No other claim is made.

Naturally, other peoples had their own ancestors. At various times, as a foreign people became significant or interesting to the Greeks, they could be attached to the Greek genealogical legends. The point was to explain how they were related to us. Thus the Latins were early declared to be descended from Latinus, who was invented and identified as a son of Odysseus by the goddess Circe, with whom he had a celebrated amour in the Odyssey; the connections reflected the fact that this people had some tinge of Greek culture.

The peoples of Scythia, a more savage and alarming lot, were given a less flattering story: they sprang from a union of the great Greek hero Heracles with a sexually aggressive snake-woman in a Scythian cave. As for the interesting peoples of Egypt and the Near East, they made their appearance in the myths in connection respectively with the Greek heroine Io (who went to Egypt in the form of a cow) and with the hero Cadmus, sprung from the same family but living in Phoenicia. Cadmus came back to Greece, bringing with him the alphabet, and became the founder of the city of Thebes; the great-granddaughters of Io, the fifty Danaids (daughters of Danaus, another eponym, this time of the Danaans, an old name for the Hellenes), returned to Greece in flight from their hated suitors, their cousins, the fifty sons of Aegyptus. Forced to marry them, all but one of the Danaids cut their bridegrooms’ throats on their wedding night: a myth which gives form to primeval and universal feelings of alarm at the thought of marrying, and being helpless in the presence of, a woman—about whom, when you came down to it, you really knew very little.

For nations who were not Greek but who had some claim to be civilized, a sort of consolation prize was devised: they could be assigned a pedigree from Troy. The most memorable example was that of the Romans, who thus gained an entry to the prestigious world of Homer and the Greek myth. Virgil gave the story classic status in his Aeneid, and in the Middle Ages the kings of Britain and of France each separately claimed Trojan ancestry; hence, for instance, the many Scots with the Trojan names Hector, Alexander, and Aeneas. It will be observed that these stories differed from those of Cadmus and the daughters of Danaus. The old Greek tales were not claims that the Greeks, or any part of them, actually descended from a foreign people, however well connected: Cadmus and Danaus were Greek by origin, Danaus actually a Greek eponym returning home. Nor is either of them a tale of conquest. Cadmus brought no army with him, and the sons of Aegyptus, though they did succeed in winning a battle and forcing the marriage, did not survive to lord it over Greece.

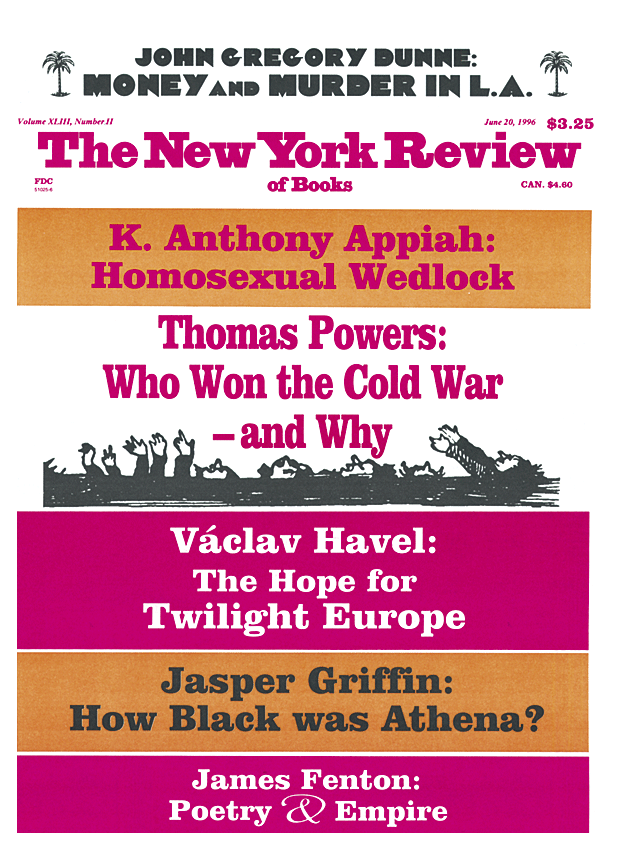

Advertisement

In the twentieth century the large book of Martin Bernal, Black Athena (two volumes so far, two more promised1 ) has put these myths to work in support of his claim that Greece was invaded, conquered, and civilized by Egyptians about 1800 BCE. Bernal, who is a Chinese scholar and an amateur in the classics, argues that somehow the memory of these events survived, distorted and disguised, in myths; and although there is no archaeological evidence for the presence in Greece of Egyptians, that presence is to be accepted as the historical truth. This invasion is to explain Bernal’s original and controversial assertion, that the origins of Greek culture, and of all the things which have traditionally been thought to come from classical antiquity, are to be found in Africa. Those notorious Dead White European Males are thus to be unmasked as mere usurpers of glory which belongs by rights to the blacks. This forms part of an attempted revision of the early history of the Mediterranean, which asserts that virtually all the creative contributions of Greece to the civilization of the West derive in reality from Egypt: an Egypt whose people and rulers were (or, in Bernal’s curiously revealing phrase, “might usefully be called”) black.

The theory has an unambiguously stated political aim (“The political purpose of Black Athena is, of course, to lessen European cultural arrogance”) and has created a great stir in North America, where conferences, books, and whole numbers of journals have been devoted to its discussion. In Europe it has not attracted nearly so much attention or been taken nearly so seriously. There, at least, European cultural arrogance has not been noticeably lessened. The book has in this respect, as in others, some resemblance to the Book of Mormon, another effort at rewriting the history of the distant past which gives a prominent role to a group (Americans, blacks) that seems rather slighted in the conventional accounts. For in the Book of Mormon the Native Americans descend from the tribes of Israel, and Jesus visited the New World immediately after his resurrection—facts hushed up in the Biblical accounts. Such stories are like some wines admirably suited for a local market, which somehow do not travel.

We now find two books devoted to Black Athena’s detailed refutation: Not Out of Africa is a short account summarizing the critical work done in different areas of scholarship which are touched on or exploited by Bernal, while Black Athena Revisited is a thorough treatment of them by no fewer than nineteen scholars, from institutions ranging from Harvard and Howard Universities to the Universities of Oxford and Rome, with an introduction and afterword by the two editors, who are both professors at Wellesley. Bernal can certainly not claim that his work has been unnoticed by academia.

These books place the reviewer in something of a difficulty. Bernal’s work ranges over a number of academic disciplines: linguistics, archaeology, the study of mythology, anthropometry, and the study of race; the history of classical scholarship; the special provinces of Egyptologists, of Greek historians, of experts in the languages and history of the ancient Near East. Its celebrity has been such that it has received critical attention from experts in all those fields. From the standpoint of scholarly inquiry and academic discussion as we know it, there can, I think, be no doubt that all the positive assertions of his two large volumes have been refuted. All that really remains standing is Bernal’s production of evidence that some scholars in the last hundred and fifty years have shared the racist views that were widespread in the society in which they lived.

That raises a large question. It is part of Bernal’s case that the professionals have been systematically blinded by racial prejudice, so that their refusal to accept his case does not really count against it. That calls into doubt the value of all the procedures of modern scholarship, in these fields and in others. Are they, in fact, just one among a possible range of approaches, all equally valid, which may lead to completely different conclusions; the conclusions all coexisting as little more than fables convenues, the question of truth being essentially irrelevant? Some people are beginning to talk as if that were what they thought. Or should we insist that the standards laboriously established by the scholars of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries really are a decisive improvement over those of the past, and that departure from or defiance of them is a grave matter calling for the most serious and meticulous justification? For we know that this will not be the end of the matter: that refutation by the accepted methods of scholarly discussion will turn out not to be the point, any more than the absence of archaeological evidence for conquest and occupation of Greece is the point.

Advertisement

Bernal’s book creates a myth; and myths of this kind are disguised statements not about the past but about the present. At some level the belief will persist that the case really has been—must have been—established, and that refutations, however detailed, are just another instance of the racial prejudices of the intellectual establishment.

That may seem unduly sweeping. Can such a vast and obviously learned book as Bernal’s be simply dismissed? It is not possible to catalog in full the arguments presented by the scholars in Black Athena Revisited. I shall set out some of the arguments which have led to their negative conclusions in three centrally important fields of knowledge, and then indicate summarily the conclusions reached by the critics in others, without being able to display the detailed argumentation which supports them.

- Linguistic arguments. Bernal makes extensive use of etymologies coined by himself, explaining the origin of Greek words and—especially—names, as deriving from Egyptian. These words are supposed to have entered the Greek language in the period of Egyptian domination, about 1800 BCE. “Black Athena” itself is one of them, since Bernal derives the name of the goddess Athena from Ht Nt, “House of Neit.” It is noticeable that a large number of these alleged Egyptian derivatives are proper names; names are the least manageable area of etymology, the most separate from a language as a whole. We do not find suggested anything analogous, for instance, to the systematic influence of French on the English language after the Norman Conquest, covering whole areas of thought and vocabulary.

We also observe that the etymologies suggested are not derived from Egyptian to Greek in accordance with any regular patterns of sound change; the same sound in Egyptian is supposed to produce quite different results in different Greek descendants. That is a return to the sort of procedure that became antiquated in the last century, as the great linguists succeeded in showing that there are regular patterns of change—“Grimm’s Law” and the rest of them—which really can be seen to apply, and which allow the scholar to predict what form a root will assume in a daughter language.

From the standpoint of modern linguistics, Jay H. Jasanoff and Alan Nussbaum, of Cornell, comment:

Hand in hand with Bernal’s lack of semantic rigor goes an almost complete disregard for phonetic consistency…. Etymologies of this kind are too capricious and unsystematic to be of any value…. Our judgment, then, is that Bernal’s claim to have uncovered “hundreds” of viable Greek-Egyptian and Greek-Semitic etymologies is simply false….

On Ht Nt itself, their comment is that

Under Bernal’s logic, it would seem perfectly legitimate to contemplate a direct borrowing of “Athena” from a feminized variant of [Hebrew] satan “Satan”….Responsible scholars will not be convinced by such linguistic sleight of hand, but the Great Deceiver would surely be amused.

Some of Bernal’s etymologies for place names suggest what would happen if one were to try to derive the names of all the States of the Union from English: the State of Connecticut for example, as one of the revolutionary states, is clearly named from a desire to break away from Great Britain; Connect-I-cut: I cut the connection. Resemblance of form is not a reliable guide to linguistic history.

- The question of race: Were the Egyptians black? Bernal insists that the ancient Egyptians were not only African but explicitly black. The claim gives his book its title, and much of its appeal. Frank M. Snowden, Jr., of Howard University, goes carefully through the ancient evidence for the perception of Egyptians, both their own—they clearly differentiated themselves from the Nubians, who really were black—and that of other ancient peoples. He concludes:

Three important points relevant to the blackness of Africans in the ancient world emerge from an examination of the copious ancient iconographic and written evidence. First, Egyptians and their southern neighbors were perceived as distinctly different physical types. Second, it was the inhabitants of Nubia, not the Egyptians, whose physical type most closely resembled that of Africans and peoples of African descent referred to in the modern world as blacks or Negroes. Third, the Bernal-Afrocentrist practice of describing Egyptians as blacks overlooks crucial distinctions made in antiquity between the physical characteristics of Egyptians and Nubians, and actually equates the two physical types.

It is an unattractive moment in Black Athena when Bernal says of this respected scholar

There is no doubt…that most Blacks will not be able to accept the conformity to white scholarship of men and women like Professor Snowden.

“White scholarship”: the phrase is a chilling one, more reminiscent than its author can have intended of such familiar notions as “Jewish science.” We had hoped for a scholarship that would be colorblind.

A professor of archaeology, Kathryn A. Bard, of Boston University, produces a judgment in accord with the observable realities of Egypt, then as now:

Ancient Egyptians were Mediterranean peoples, neither Sub-Saharan blacks nor Caucasian whites but peoples whose skin was adapted for life in a subtropical desert environment. Ancient Egypt was a melting pot….

And finally, from an anthropometrical standpoint, C. Loring Brace, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Michigan, writing with five professional colleagues, concludes that:

Whatever else one can or cannot say about the Egyptians, it is clear that their craniofacial morphology has nothing whatsoever in common with Sub-Saharan Africans’. Our data, then, provide no support for the claim that there was a “strong negroid element” in Predynastic Egypt.

In fact, from a scientific point of view,

Attempts to force the Egyptians into a “black” or “white” category have no biological justification.

- Myths and History. It is central to Bernal’s case, especially in the absence of the archaeological evidence which one would expect to find for Egyptian occupation of Greece, that it is possible to extract precious historical truth from Greek myths of a thousand or more years later. We have already seen that the myths in fact represent Cadmus and Danaus not as foreigners but as returning Greeks. But there is a much more general point. Myth has been the object of much study in the last century, and we have learned that a people’s myths have many other purposes than the preservation of anything which we could treat as history. They contain speculations on the nature of life and death, the nature of animals, the relation of the species, the origin of cults and rituals, customs and anxieties about marriage and about the relations of the sexes and the generations, as well as claims for the ownership of land, and charters for every other form of inherited custom and institution.

All of this is simply disregarded when the myths are treated as an essentially uniform set of garbled historical statements, which we can decipher to read the message which we were in any case expecting to find. Edith Hall, of Somerville College, Oxford, writes:

Are we to abandon the sophisticated theories of the twentieth century which have helped us to understand how mythology works? Are we going to return to a simple nineteenth-century model which ignores all the post-Malinowskian, post-Freudian, and post-Lévi-Straussian work on myths as ideological charters for social institutions, as expressions of subconscious desires, or as mediators of abstractors of concern to the contemporary world? Are we to ignore all the work done by social scientists in recent decades, since Weber’s pioneering labors, on the way subjective ethnicity is constituted? Accepting Bernal’s “Revised Ancient Model” requires us to do all this.

It is not possible here to go through every sort of claim and give even a summary indication of the argumentation for its rejection. Robert Palter, Professor of the History of Science at Trinity College, Connecticut, examines in detail Bernal’s claim that the Egyptians had true science long before the Greeks, and that Greek astronomy, mathematics, and medicine were profoundly influenced by the corresponding sciences in Egypt, and concludes that it is untenable. The archaeologist Emily Vermeule, of Harvard, reviews and rejects from the archaeological point of view Bernal’s ambitious rewriting of the accepted history of the second millennium BCE, sending the Hyksos pharaohs of Egypt to colonize Greece, and Egyptian armies to conquer the eastern end of the Black Sea; while from the specifically Egyptological side, the Egyptologists David O’Connor, of the University of Pennsylvania, and Frank J. Yurco, of the University of Chicago, equally find Bernal’s thesis untenable.

Even on his strongest ground, the detection of racism in scholars of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, where he presents some interesting and revealing material, Bernal damagingly overplays his hand. Robert E. Norton, professor of German at Vassar College, shows that the great Johann Gottfried Herder is guiltless of the charge of racism that Bernal brings against him; an apparently damning statement which he “is reported as having said” turns out, when actually quoted, to have the opposite meaning. And Guy MacLean Rogers, of Wellesley, successfully defends the historian George Grote, who is, for Bernal, a romantic and probably a racist. In life, he was a determined anticlerical, one of those who insisted that London University should be open to Jews and Nonconformists—that it should be, in the phrase of Arnaldo Momigliano, an institution “born in liberty for liberty.”

A couple of general judgments seem to me to sum up correctly the views of the more than a dozen scholars who have examined Bernal’s arguments in detail. John E. Coleman, of Cornell, says of the book as a whole:

The lack of scholarly method, of “disciplinary rigour,” is everywhere apparent. As a consequence, Bernal’s work has been almost universally rejected by Egyptologists, archaeologists, linguists, historians, and other scholars best acquainted with the material evidence. Most regard it as beyond the boundaries of legitimate scientific inquiry.

Mario Liverani, of the University of Rome, is no less severe:

The scholars of the mid-nineteenth century established the very “rules” of philological method…. All these professional rules can of course be improved upon or even replaced by demonstrably better rules; but they cannot simply be dismissed out of hand without providing a substitute. What Bernal does is to go back to a pre-paradigmatic behavior. He does without a methodology: he interprets sources at face value, avoids a critical evaluation of traditions, suggests etymologies by simple assonance, confers on myths the value of true history, and limits his primary and secondary sources to those which confirm his own perceptions. His treatments of etymology and mythical tradition are especially incompetent, and unfortunately most of his conclusions are built on them.

An ordinary scholarly book, receiving such crushing criticism on so many fronts, would be annihilated. It can be predicted with confidence that such will not, in North America, be the fate of Black Athena. The new myth which it presents meets a felt need. In the words of Mary Lefkowitz, the desire to believe in African origins for Greece

is strictly a twentieth-century phenomenon, specific to this country and to our own notions of race.

How are its consequences to be described? Frank M. Snowden has grave words of warning:

It is unfortunate that Afrocentrists fail to realize the serious consequences of their distortions, inaccuracies, and omissions, and the extent to which the Afrocentrist approach to ancient Egypt has motivated many blacks to stir up anti-white hostility. Substituting fiction for fact is a disservice to blacks. The twentieth century has already seen sufficient proof of the dangers of inventing history. What will be the effect on future generations, black and white alike, if the present “mythologizing” Afrocentrist trend continues, and if the historical record is not rectified? The time has come for scholars and educators to insist upon truth, scholarly rigor, and accuracy in the reconstruction of the history of blacks in the ancient Mediterranean world.

It must be said that some features of Bernal’s scholarly style do nothing to diminish this effect. It is determinedly polemical, with a constant implication that those who disagree, past and present, are motivated by racism: a catch-all charge that seems to fit every defendant. He also is quick to hint at conspiracies where none exist. It is not surprising that Sarah P. Morris, of the University of California at Los Angeles, comments sadly:

An ugly cauldron of racism, recrimination, and verbal abuse has boiled up in different departments and disciplines; it has become impossible for professional Egyptologists to address the truth without abuse, and Bernal’s arguments have only contributed to an avalanche of radical propaganda without basis in fact.

Mary Lefkowitz has also produced a book that tackles the wilder extremes of the Afrocentric doctrine being taught in some schools and universities. This makes such assertions as that Aristotle derived (“stole”) his thoughts from the perusal of African books in the Library at Alexandria, despite the absence of any ancient evidence for that view and the presence of evidence that: Alexandria did not exist before it was founded as a Greek city by Alexander the Great; the Library was founded only after the deaths of Alexander and Aristotle; the Library did not contain African books; Aristotle never went to Alexandria. In addition, and this is perhaps the most important point of all, no African, or Egyptian, books have been produced which resemble those of Aristotle, and there is no reason to suppose that any ever existed.

In the literature Lefkowitz describes, it is accepted that Socrates was black, though there is no hint of it, even in Aristophanes’ hostile and comic presentation of him in the Clouds. It is also accepted that Cleopatra, who was from a Macedonian dynasty, was black—a fact, again, never mentioned in all the hateful and invidious propaganda about her as an opponent of Augustus. These assertions and the persistence with which they are made in the face of refutation form a fascinating study in morbid collective psychology, well and temperately set out by Lefkowitz. But the implications are worrying. Some academics now say, and others think, that it does not matter whether these assertions are based on evidence or not, or whether they do or do not stand up to dispassionate scrutiny. It is the specific function of universities not to behave in that way, but to insist that it matters whether or not Aristotle stole his doctrines, or Socrates was black, or the Holocaust took place.

2.

And must it always be so, asks the saddened reader? Can there be no rational discussion, free from hatred and the crude excesses of ideology, of questions of cultural influence? It is a pleasure to turn to more measured and reasonable debates.

It must first be said that the Greeks themselves were quite happy to admit that they had learned important lessons from other peoples. They ascribed the introduction of their alphabet to Cadmus, who brought it from Phoenicia; it is indeed often called “the Phoenician letters.” They did not even insist, as they might have done, that by the innovation of writing out the vowels they had transformed the utility of that alphabet (and turned it into the one that most of the world continues to use). They were well aware that in astronomy they had learned from the Babylonians, in sculpture from the Egyptians.

In recent years there has been a great movement among classical scholars in the direction of finding sources and models for Greek literature and thought, not indeed in Egypt, but in the ancient societies of the Near East. The reason why there is much more of this research now than there was in the nineteenth century is not simply that earlier scholars concealed the evidence because they were all racists and anti-Semites. It has vitally to do with the fact that we can now read so much that they could not. Nineteenth-century scholars were not in a position to assess the significance for early Greek literature of the literatures of Ugarit (in Syria) and of the Hittites (in Anatolia), because they had not yet been deciphered. When they were, classicists immediately began to work on their implications. T.B.L. Webster’s From Mycenae to Homer, with its substantial chapter on “Eastern Poetry and Mycenaean Poetry,” appeared in 1958. If I may be permitted a personal reference, I wrote in 1980 that “it seems pretty clear that Homer and Hesiod were influenced from Eastern sources”2 and made quite extensive use of such material in my book, not as a daring pioneer facing ostracism from racist colleagues, but as a matter of course.

The central reason why in the nineteenth century classicists stopped thinking of Egypt as a source for Greek thought and literature is, again, not racism: it is the mirror image of the situation with the Eastern texts. Once it became possible to read Egyptian texts, scholars could see that, in this case, there was very little resemblance indeed between them and the Greek. No amount of speculation about the possible historical content of myths can make up for that cardinal fact. What did strike Greeks in Egypt was the look of things, the imposing statues and the colossal temples. That, not literature, was the Egyptian legacy.

If there is one country that does not need to feel apologetic or apprehensive about its contribution to Western civilization, it is surely Italy. Yet there have been times when some zealously patriotic Italian writers have tried to play down the Greek contribution both to the arts of Rome and to those of Italy as a whole. In the eighteenth century G.B. Piranesi, the great etcher and creator of the haunting Prisons, was a passionate archaeologist and art historian, and one aim of his work was to show that the indigenous Italian element in Roman art was much greater than his contemporaries supposed. A “Tuscan” order of architecture was invented, to stand beside the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian; the Greek vases found in Etruria were assigned to Etruscan rather than Greek potters and painters. It is surely a sign of cultural health that now the Italians are happy to stage a blockbusting exhibition on the theme “The Greeks in the West,” currently on view in the splendid setting of the Palazzo Grassi in Venice.

The first Greeks to have dealings with the West arrived in the second millennium BCE; their traces can be found in Sicily and near Taranto in southern Italy. The great period, however, begins in the eighth century BCE, with the establishment of the Greek settlements which used to be called “colonies,” but which the organizers of the exhibition prefer nowadays to call by a less loaded name. No wonder, perhaps, when the separatist party the Northern League was campaigning in Venice, before the recent election, with the slogan: “Halt Colonialism! Enough of taxes! Enough of Rome!” It is indeed not very satisfactory to call the Greek settlements colonies. They each derived from particular cities of Aegean Greece but they were not governed from the mother city, nor did they pay it taxes. They were in fact independent city-states, under pressure not from a colonial power in mainland Greece, but on the one side from the Carthaginians in the west of Sicily, and on the other from the greatest and most aggressive of the Greek cities: Syracuse.

The exhibition is on a generous scale. The visitor confronts statues, plans and photographs of temples and cities, pottery, paintings, and jewelry from many museums, particularly in Taranto, Naples, Rome, and Paris. On the walls are short accounts, intelligently chosen and well displayed, of many aspects of the culture of the Greeks in the West. The texts give examples from the poetry and philosophy they produced there, such as works by the philosopher and wonderworker Empedocles and the great lyric poet Pindar. They also give brief accounts of the Greeks’ interactions with the peoples whom they met there. Those relations varied a great deal. The native peoples of Sicily, the Siccls and Sicans, found themselves pushed away from the coast, where the Greeks built cities accessible from the sea; their culture was soon overwhelmed by the elegancies of Greek art and life. The Carthaginians proved much tougher in resisting Greek culture. Carthaginians and Greeks fought each other for centuries, neither side ever being able to drive the other out of Sicily.

The influence of Greece was in the end great, as can be seen for instance from the beautiful but very Greek coins struck by Carthaginian mints in the fourth century BCE. The spectacular buildings of Akragas (Agrigento) were largely built by Carthaginian prisoners of war after the great Greek victory at Himera in 480; less publicized in the modern world is the Carthaginian revenge, when in 409 they destroyed the city of Akragas and others in western Greece. Italy contained resistant peoples, too, and in the end it was mostly round the Bay of Naples that the Greek presence remained strongest through the Roman period; though the Etruscans and, partly through them, the Romans developed and transformed the Greek tradition in art and literature, in ways that were to be formative for Europe.

The exhibition brings together some objects which gain in suggestiveness from this proximity—above all, perhaps, two extraordinary works of early classical sculpture: the two so-called “thrones,” the Ludovisi Throne, normally in Rome (see photograph on page 67), and the Boston Throne, normally in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Carved on three sides with lifelike and haunting sculptures, these monuments were perhaps altars. It is fascinating to see them in the same room, especially as that room contains a full account of the long argument over the question whether the Boston Throne is genuine or a recent fake. This visitor felt (rather, perhaps, than judged) that it is genuine, but not so fine.

It is the aim of the exhibition to offer “the most complete picture ever attempted of Greek civilization in the West, with particular reference to the Italian peninsula and Sicily.” That claim is well borne out by the wealth of the exhibits and the elegance and lucidity of their display. Less familiar for English-speaking scholars is the explicit proclamation by the coordinator of the project that:

As far as possible, the choice of the exhibits has been based on aesthetic criteria…. The most beautiful works have been chosen in an attempt to exemplify one of the most important insights of the Greek mind, that of considering the aesthetic dimension to be a fundamental component of the human experience, so that, of all the perceptive faculties, pride of place was offered to the visual one.

And the Minister for Cultural and Environmental Assets goes so far, in his introductory remarks, as to say

The exhibition must take place under the banner of pure beauty, without compromise or confusion.

That is not the way our own politicians talk, or our scholars, either. One cannot fail to connect it with the smart appearance, by our standards, of modern Italians: these are people for whom, as for the Greeks, the look of things is important. It goes also with the fact that there is in the exhibition less emphasis than we would expect in Britain or North America on demography, sanitation, crops, diet, tooth decay, coprolites, and all the somber and unaesthetic aspects of the past that have so largely ousted the beautiful. This is emphatically a handsome exhibition, with the emphasis on the arts of civilization and pleasure. There are splendid objects used for the feasting that was so important a part of that society, as well as statues, silver, jewelry, and objects used in the theater and for perfumes, wine, and bathing. Religion, in which the Sicilian Greeks had a special taste for cults of mysteries and salvation, is also prominent. On show are the gold tablets buried with the dead, bearing instructions in verse for the posthumous journey of the soul.

The wall labels are also well written, both in Italian and English throughout, and the many groups of schoolchildren who visit are surprisingly attentive to the written matter as well as to the spectacular objects on show. There is a lot to be learned, and about a crucial encounter: it was the impact of Greece on the Etruscans and early Romans that created the conditions for the Roman Empire, and with it for the survival in the West of at least some of the achievements and values of classical Greece. The exhibition is intelligent as well as attractive, and any reflective visitor will come away with plenty of food for thought. We can see the extent, and the limitations, of the influence of one culture on another: the Greek cities remained determinedly Greek, as long as they could. Others absorbed more or less from them, sometimes producing, as in the case of the Etruscans, a civilization that was heavily Hellenized, especially in the arts, and that used an alphabet derived from the Greeks, but was nonetheless clearly and characteristically different.

It is a pity that the lavish, splendid, and weighty catalog, subsidized by Fiat and in some ways a most desirable possession, contains a useless index, which refers the inquirer in search of the Ludovisi Throne neither to its number in the list of exhibited works, nor to the handsome double-page color illustration of its central panel, but only to an incidental reference on page 64. It is a pity, too, that it contains so little systematic illustration and discussion of the actual objects on show. While there are splendid reproductions of a large number of artifacts that not only do not appear in the exhibition but have no particular connection with it, such as the Attic vases which illustrate a general chapter on “Greek Pottery and the Role of Athens” (itself perhaps a surprising inclusion), and such familiar sculptures as the Winged Victory of Samothrace and the Great Altar of Pergamum (“An Outline of Hellenistic Sculpture”), the photographs of the listed exhibits are black-and-white and the size of postage stamps, accompanied by the most exiguous descriptions imaginable.3

It is impossible to resist the temptation to add that the catalog will be read with little pleasure by Martin Bernal. It serenely disregards his onslaught, taking it as axiomatic that

The foundations of today’s mentality and morality lay [read “lie”] on the Greek heritage. The fundamental canons of both individual and collective ethics descend from Greek culture and continue to permeate our own.

No revisionism there, or in the chapters by Italian scholars. In conclusion, it ought to be said that a whole crop of lesser provincial exhibitions is accompanying the central Venetian one, all over southern Italy. They, too, have lavish catalogs, published by Electa Napoli.

3.

The visual arts of Greece were powerfully influential, not only in Italy and Sicily but in less classical parts of the Roman Empire and far beyond its frontiers, among Celts, Semites, Indians, Persians. Sir John Boardman, of Oxford, sets out to illustrate that influence in a highly original book, illustrated with relevance as well as lavishness, based on his A.W. Mellon Lectures of 1993. He aims to

explore the record of Greek art as a foreign art introduced to peoples who may have had strong artistic traditions of their own, and who had no extravagant views about the splendours of Greek Art and Greek Thought (many, indeed, probably despised them).

His book’s purview includes the early city of Rome, for which Greece was influential but essentially foreign, but not the “classical” period of Roman art, beginning in the third century BCE, when a relationship that began as a simple looting of the products of a superior culture settled into an amalgam, in which the originally Greek elements formed overwhelmingly the majority. Most of the book concerns more exotic and less familiar regions that absorbed Greek arts, particularly sculpture. The perspective is an interesting one, and it does not mean that the others, the non-Greeks, were simply waiting for the Greek tradition to come along and show them how to do it. Boardman’s account affects our perspective on Greek art, too. It is too easy to see its changing styles as simply a “natural” progression, like the growth of a plant, but comparison with other traditions brings out the extraordinary pace of Greek development and change, hard to parallel in the history of art. That was not inevitable, as we see when we look at the uses to which other cultures put Greek models.

What were the aspects of classical Greek art which influenced foreigners? Boardman singles out the prominence of the naked human body; the startling and unprecedented realism—so much more startling when the sculptures had their bright paint—which made illusionism possible; and the pervasive patterns of ornament: the meanders, leaf patterns, convolvulus, and acanthus. The Persian kings who conquered the Near East came from a nomadic background. To devise a style for their palaces they imported Greek artisans and applied Greek motifs, adapting them to a taste which was ornate, uninterested in anatomy and the nude, and making use of Greek shapes without concern for their original significance. The pillars of Persepolis had capitals of true Hollywood elaboration and magnificence.

We find in the Phoenician city of Sidon (in present-day Lebanon) extraordinary sarcophagi, Egyptian in general form, but with the traditional Egyptian head and headdress of the dead replaced by a handsome head in the classical Greek style. In the east, the Parthians produced splendid sil-ver plates on which basically Greek scenes, like Heracles reclining at a banquet, are progressively reinterpreted in a more and more exotic style and conception, as we can see from some striking instances that survive. From the Oxus to the Ganges, in the last two centuries BCE, we find “almost an artistic koine,…thoroughly hybrid in its derivation, and betraying western influences to different degrees in different places.” The human representation of the Buddha, a standing figure, was developed in Eastern art only under Greek influence: before the Eastern conquests of Alexander, the Buddha was represented only by a symbol, a footprint or a tree or a throne.

There was nothing in earlier Indian statuary to suggest such a treatment of form or dress, and the Indian pantheon provided no adequate model for an aristocratic and wholly human deity.

Boardman is anxious to avoid the excesses of local particularity which beset specialists, tempted to defend and glorify their own field. He sees in the best Egyptian sculptures “qualities which go beyond the blend of real and ideal achieved by the Greeks, perhaps through their ability to add an element of the immortal.” He insists that artistic influence was not a one-way process: observing, of one particularly controversial area of such studies,

Over the last hundred years scholarly argument over the relative roles of Phoenicians and Greeks in the early history of the Mediterranean, or indeed in the history of the western world, could easily leave the impression that the two peoples were born antagonists. The dispute can often be explained by anti-or pro-semitism (sometimes barely concealed)…. The extreme views on this matter are nonsense, supported by a degree of selectivity and distortion in handling of evidence that would be more appropriate to a pre-election politician.

His own account of all this, and of the relations of Greek art with that of the peoples of the Black Sea, Spain, Egypt, and Italy, is as urbane in manner as it is penetrating in detail. He quotes, as a reproof to some contemporaries, from Lytton Strachey’s Queen Victoria:

Strachey recounts how Prince Albert visited Italy just before his marriage to Queen Victoria: “When the Pope (Gregory XVI) observed that the Greeks had taken their art from the Etruscans, Albert replied that, on the contrary, in his opinion, they had borrowed from the Egyptians: his Holiness politely acquiesced.” Politeness is not enough, but it is a good start.

This Issue

June 20, 1996

-

1

Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, Volume I, The Fabrication of Ancient Greece 1785-1985 (Rutgers University Press, 1987), Volume II, The Archaeological and Documentary Evidence (Rutgers University Press, 1991). ↩

-

2

Homer in Life and Death (Oxford University Press, 1980), p. xv. ↩

-

3

Of the two thrones, for example, only two sides (of three) are illustrated, even in that niggardly form; and while many of the objects in the list are nobly illustrated somewhere in the book, there is no way of discovering that except guesswork or the perusal of the entire volume. The “catalog” is in fact a collection of chapters, some of them quite hard going, amounting to something like a general account of the Greeks, with special reference to the West. Those who go to the exhibition will be well advised to leave it behind, or to buy it on the way out, and keep it for home browsing. ↩