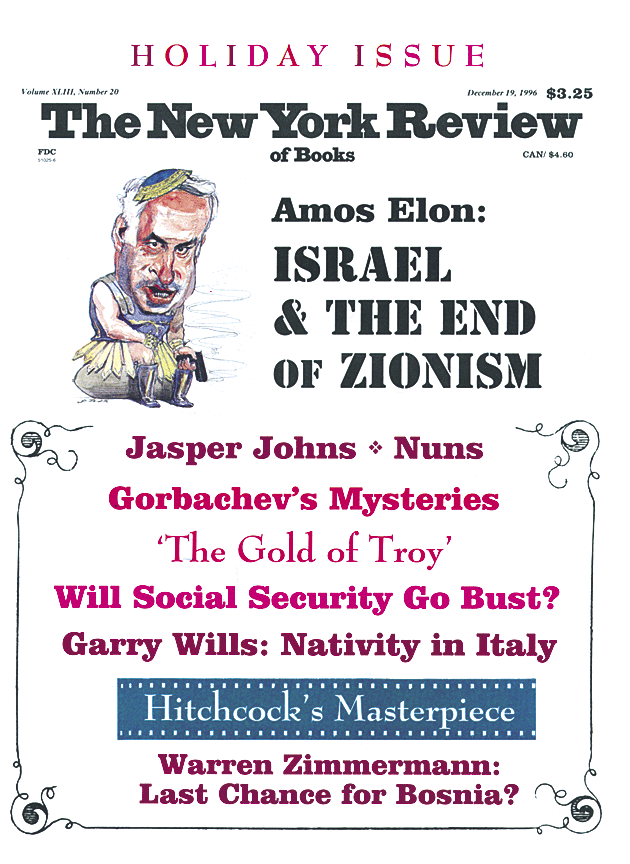

Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo is no less strange and singular now than on its original appearance in 1958. Visible for years only in a cramped, splotchy, and faded video transfer, it has now been rereleased in wide-screen proportions, brilliantly restored colors, and almost too brilliantly restored sound (each passing thud and squeak carries almost as much sonic weight as Bernard Herrmann’s incomparable score). If Vertigo at first aroused at best muted and scattered appreciation, the response to its reemergence has been apparently enthusiastic consensus that the film is indeed not only Hitchcock’s summing up but one of the masterpieces of the last half-century of movies.

Yet what a peculiar sort of masterpiece it is. Centrality is an uneasy position for a film so wedded to offcenteredness. As a cultural monument, Vertigo resembles a Hollywood spectacle seen through the wrong end of the telescope, marshaling vast and spacious resources toward an ineluctably inward and downward spiral. In the heart of the expansive 1950s, Hitchcock succeeded in making a movie of epic proportions (the city of San Francisco is enlisted as a virtual character in the drama) about the narrowing and finally the elimination of human possibilities. It is something like an amusement park ride that—after beguiling its passengers with an intricately linked series of illusions—for its final flourish ejects them into free fall.

What has become clearest over the decades is the extent to which this uncanny machine instills permanent fascination in some of the people who see it. Such devotees seem fated to reenact Vertigo’s central gesture—the meticulous but fruitless attempt to recreate a lost love object—with regard to the movie itself. The painter David Reed, who has used a still of Kim Novak in her hotel room as the basis for several installation pieces, is, according to Arthur C. Danto, “enough obsessed with Vertigo that he once made a pilgrimage to all the remaining sites in San Francisco that appear in Hitchcock’s film.”1 The filmmaker Chris Marker has similarly revisited the stations of James Stewart’s obsessive wanderings—Ernie’s restaurant, where he first catches sight of Kim Novak, the florist’s where he spies on her from behind the door, the spot where she throws herself into San Francisco Bay—and the record of this journey forms a crucial portion of his cinematic essay Sans Soleil (1982).

The examples continue to multiply. Terry Gilliam in his film 12 Monkeys (itself an adaptation of another Chris Marker work, La Jetée, which elaborates ingeniously on Vertigo’s recursive narrative spirals) incorporates a scene from Vertigo so that his doomed lovers can share their last hours of freedom with Hitchcock’s doomed lovers. Victor Burgin in his photographic essay Some Cities 2 repeatedly invokes Vertigo’s storyline and inserts a still from the film—Barbara Bel Geddes walking down the corridor of the mental hospital—into his collage of urban spaces. Louise DeSalvo in her recent memoir entitled simply Vertigo3 describes her compulsive repeated viewing of the film on its first release, and relates it to her discovery of her own undiagnosed vertigo.

Beyond these explicit citations, more movies than could be listed have by now adapted Vertigo’s narrative strategies, from Brian De Palma’s Obsession (a near-remake, complete with a Bernard Herrmann score) to Paul Verhoeven’s Basic Instinct (whose cinematographic textures and musical motifs pay elaborate tribute to the Hitchcock film even as the movie itself raunchily explodes Vertigo’s mood of mystical romantic devotion). Indeed, that most reliable stock figure of contemporary made-for-television melodrama, the obsessional stalker, might be seen as the degraded descendant of James Stewart’s Scottie Ferguson.

Yet Vertigo is not one of those movies, like Casablanca, Singin’ in the Rain, or Hitchcock’s own North by Northwest, that evoke the warm glow of collective enjoyment. It tends rather to turn the members of the audience in upon themselves, to remind them precisely of what they cannot share with their fellow spectators. I can speak with some experience in this matter, having seen Vertigo at least thirty times over the years.

In the case of most movies, a spectator’s personal obsession may seem the result of accident, a matter of circumstance and timing. With Vertigo the obsession feels to an unusual degree predetermined. Hitchcock was after all the director who beyond all others took a virtually scientific interest in anticipating and shaping the spectator’s response (“I feel it’s tremendously satisfying for us to be able to use the cinematic art to achieve something of a mass emotion”)4 ; he would later famously remark that he didn’t have to go into the theater to hear the audience screaming at Psycho. Would it be too far-fetched to surmise that, having long since mastered the arts of instilling excitement and anxiety, he might have undertaken the more challenging task of inducing obsession in the spectator, if only for the duration of a movie? Or that he could even have foreseen that such an obsession, once rooted, might well last a lifetime? The multiple-repeat viewer of Vertigo has the impression sometimes of submitting to a process prepared long in advance. He submits, perhaps, in the hope of getting closer to the film’s real subject—when that subject is nothing other than his own carefully programmed response, his state of entranced alertness.

Advertisement

One of the curiosities of Vertigo is its capacity to generate emotional power from a plot that lacks the most elementary believability. We are required to accept not an isolated implausibility but a continuous stream of them. For the benefit of viewers unacquainted with Vertigo (if there still are any), the following is a summary of the plot:

San Francisco police detective Scottie Ferguson (James Stewart) resigns from the force when his acrophobia leads accidentally to the death of a fellow officer. Midge (Barbara Bel Geddes), an old girlfriend, seems to be his only close friend. An acquaintance from college, the shipping magnate Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore), hires Scottie to follow his wife Madeleine (Kim Novak); she appears to be dangerously obsessed with her ancestor Carlotta Valdez, who went mad and committed suicide. As Scottie follows Madeleine through places associated with Carlotta (a museum containing a portrait of her, a graveyard, an old hotel where she once lived), he falls in love with her. She attempts suicide by jumping into San Francisco Bay; he rescues her and they meet, ultimately acknowledging their mutual love.

Madeleine is haunted by nightmares of impending death, but Scottie is convinced he can save her by finding a rational explanation; believing that her most vivid dream refers to the old mission at San Juan Batista, he takes her there. She runs up the tower; unable to follow her because of his acrophobia, he watches helplessly as her body falls from the top.

After the inquest at which the death is declared a suicide, Scottie succumbs to depression and catatonia; Midge, unable to help him, walks out of his life. Partly cured, he wanders the city disconsolately until one day he meets Judy Barton, a woman who strongly resembles Madeleine although different in obvious respects (brunette not blonde, a shopgirl not a socialite). In a flashback from Judy’s point of view, it is revealed that she and Madeleine are one and the same; she played the role to assist Elster in his plot to murder his wife, who was already dead when her body was thrown from the tower.

Judy decides not to flee because she loves Scottie and hopes he will come to love her for herself rather than because she looks like Madeleine. He sets about trying to make her over through changes in clothing and hair color, finally achieving an exact resemblance. When he sees her wearing a piece of Carlotta’s jewelry, he realizes he has been duped and leads her back to the tower, dragging her to the top and extorting a confession. A nun appears out of the darkness and Judy, terrified by the shadowy apparition, falls to her death.

Far from undermining the movie, the implausibilities make it stronger, more exhilarating, as if their proliferation confirmed that we are in the country of desire where anything can happen. The fairy-tale atmosphere makes Scottie’s instant eternal passion for the beautiful sleepwalker Madeleine not only acceptable but inevitable.

By taking as his source the novel D’Entre les Morts by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac (the team responsible for Diabolique), Hitchcock plugged into a long-established French tradition of fantastic crime fiction that encompasses the novels of Maurice Leblanc, Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre, Gustave Lerouge, Jean Ray, and, more recently, Sebastien Japrisot and Delacorta. It is a tradition that prizes the outré incident, the eruption of dream material into the fabric of the everyday, far more than any patient building up of circumstantial verisimilitude: so much so that by the light of Arsène Lupin and Fantomas, Surrealism can begin to look like little more than an extended gloss on French popular culture.

Not that the novel has anything of the film’s romantic tinge; its tone is rather glum and sordid, set against the catastrophe of the fall of France and with the detective a cringing and self-lacerating character who ends by strangling the woman who has betrayed him. Hitchcock takes only the bones of the story. If he had filmed it straight it might have come out like one of those unexpectedly grim little B-movies which cropped up along the fringes of Hollywood filmmaking in the 1940s, tales of garish crimes and last-minute reckonings like My Name Is Julia Ross or So Dark the Night or They Won’t Believe Me.

Advertisement

Instead he adopted a tone reminiscent of a more upscale Forties cycle, the string of lushly romanticized supernatural fantasies like Portrait of Jennie and The Uninvited. The first half of Vertigo seems almost a throwback to that short-lived genre, an impression to which Bernard Herrmann’s music, echoing his earlier score for The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, contributes powerfully. This is the closest Hitchcock came to the realm of supernatural fantasy, a mode that appealed to him strongly enough that for decades he sought to film James M. Barrie’s 1920 ghost play Mary Rose, with its time warps and its ageless woman inhabiting a magical isle. (Vertigo’s poignant harping on the theme of love reaching out from beyond the grave undoubtedly owes more to such sources than to the Orpheus myth, Tristan and Isolde, or Asian ghost stories like the one that inspired Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1953 film Ugetsu.)

For Barrie, dream worlds like Mary Rose’s island retain an eternal if tenuous existence; for Hitchcock, there was no opportunity to sustain such a fantasy even for the length of a movie, however much he may have wanted to. Vertigo wouldn’t feel so much like a tragedy if its first half, its fantasy half, weren’t put together with such evident love. You can almost believe that the director wants things to turn out differently, wants the film to culminate in the fulfillment of Scottie and Madeleine’s cosmic passion. Instead he is obliged to reverse the Hollywood formula, which traditionally wraps up a sequence of vicissitudes with an embrace at the fade-out, by saving the ultimate vicissitude for after the last kiss. If the traditional Hollywood three-act plot structure can be diagrammed as love/loss/love, Hitchcock’s expanded five-act structure becomes loss/love/loss/love/loss, or more specifically fatal fall/orgasmic embrace/ fatal fall/orgasmic embrace/fatal fall.

Hitchcock had been increasingly concerned with embraces, considered as a formal problem. The emotional poles of most of the films ever made are only two: avoidance of Movie Death and desire for Movie Love. Hitchcock had been typed as a specialist in murder, but from Rebecca on he clearly wanted to appropriate the power of Movie Love. It was after all the cheapest yet most indispensable commodity, an alchemical brew slapped together with soft-focus close-ups, swelling theme music, and slow fade-outs: the ultimate Hollywood cliché, something that anyone could do, with full confidence in its effectiveness no matter how shoddily they did it. As with chases and murders, Hitchcock seems to have been fascinated with the idea of taking the most obvious device and doing something different with it.

Throughout the 1940s Hitchcock worked at managing something as distinctly original in the romantic line as he had already accomplished in the suspense and adventure lines. It was this shift toward the woman’s picture, the most important genre of filmmaking in Forties Hollywood, that led critics to denounce his American movies as soppily unworthy of the maker of The 39 Steps and The Lady Vanishes. It wasn’t that the English movies lacked a romantic component, but that their archetypes—bright young ingenues like Madeleine Carroll and Nova Pilbeam, roguishly witty leading men like Robert Donat and Michael Redgrave—were more acceptable to American critics than the glossy likes of Gregory Peck and Ingrid Bergman in Spellbound.

In fact Spellbound, an uneasy depiction of true love (denoted by violins) cutting through the entanglements of Freudian trauma (denoted by solo theremin), stands as something of an aesthetic disaster, at least by comparison with its magnificent successor. In Notorious, Hitchcock’s most achieved love story, the troughs and crescendos of the troubled affair between Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman (troubled especially and understandably by her forced marriage to Nazi agent Claude Rains) are made to dovetail seamlessly with the rhythms of the suspense mechanism, so that the lovers’ final embrace seems in the same instant to destroy the Nazi conspiracy and to resolve all romantic confusion.

In Notorious the glamour machinery of Hollywood is exploited to its fullest. Every element, from Edith Head’s costumes to Ted Tetzlaff’s sinuous tracking shots through ornate “Brazilian” interiors, suggests a world suffused with exotic sexuality. On that level Notorious resembles a sleek and slinky piece of Forties pop music like Artie Shaw’s recording of Innuendo. Within those shiny trappings, Hitchcock is free to choreograph an intricate and quite merciless dance of desire and contempt and desperate last-minute retrieval, almost without anyone noticing.

Hitchcock was never more in tune with the stylistic currents of his day; nor was he ever again to suggest such a healthy glow of erotic feeling. In the films that followed Notorious (The Paradine Case, Rope, Under Capricorn) he strayed increasingly from what was expected of him, with commercially disastrous results. Of these the most interesting was the biggest failure of his career, Under Capricorn. The nineteenth-century backdrop of this exercise in Australian Gothic provided a suitably remote and spacious frame for virtual arias of camera movement, extravagantly protracted takes in which the characters were closely stalked as they passed through the stages of self-destructive remorse, hopeless infatuation, jealous rage, and liberating confession. Here Hitchcock made it clearest where he really wanted to go—into a rigorous yet operatic playing out of emotional roles—only to discover that audiences had little desire to follow him there. He would find his way back to favor with more tart and emotionally restrained entertainments along the lines of Strangers on a Train and Rear Window: in other words, to the pointed, ironic mode with which he will remain primarily identified. Grand romantic passions would drop altogether out of sight until Vertigo provided him with the opportunity to pull the stops out one last time.

If the director wants grand opera, the audience prefers crossword puzzles, the sort of thing he has been doing effortlessly since the days of The Lodger and Blackmail. He had developed early on those tricks of cognitive shorthand, of rapid wordless exposition, which became the trademark of the “master of suspense.” His method mimics the process of thinking, so that each shot seems to follow logically from the one before. Wary of ellipses and interludes, he strenuously avoids the lyrical patches and intermittent sightseeing with which commercial movies customarily fill out their running time. The spectator is made to feel that every shot counts, that every bit of business is moving the intrigue directly forward.

Any situation can be broken down into a series of unmistakable messages, almost in the fashion of an educational movie on how salmon is canned. Along the way there are the equivalent of review tests, as if Hitchcock the conscientious pedagogue will not go on to the next lesson unless assured that the whole class is with him. His approach at its most elementary can be found in the sequence in Notorious that tells us, in three shots, that the wine bottle next to Cary Grant (1) is being nudged out of position, (2) is getting dangerously close to the edge, and (3) has crashed to the ground. Narrative proceeds by such small and precisely measured units of exposition: three shots, neither more nor less, are called for to keep the audience up to date on the state of affairs. Hitchcock’s declaration in a 1940 interview that “my slogan is ‘keep them awake at the movies”‘5 pretty well sums up his primary concern with regulating the spectator’s attention span.

The filmmaking problem that concerns Hitchcock above all is how to transmit information—information, that is, about what is going on in the movie. His films are for the most part closed systems, and the spectator needs to know almost nothing of the outside world to follow his narratives. From the whole body of his work one could deduce that World War II had occurred, but very little else about twentieth-century history; as late as the 1950s his films of intrigue like The Man Who Knew Too Much and North by Northwest still involved unnamed foreign powers and mysteriously undefined state secrets.6

Children delight in Hitchcock’s clarity; they gravitate to his films because they can understand what is going on. They find immense satisfaction in a game whose rules are so plainly established. Any ten-year-old can analyze the point of every glance, every gesture. The movie is entertaining because every element has a legible function and no part is merely to be endured while waiting for the real business to begin: in Hitchcock’s often repeated phrase, it is “life with the dull bits left out.” As for content, that amounts—in principle, at least—to little more than an afterthought.

Hitchcock could have continued to elaborate endlessly on the formulas of The 39 Steps and Foreign Correspondent in a string of elegant variations on the chase movie; clearly, many people hoped he would do so. Instead he looked for material that would push the limits of his established methods. Vertigo was undoubtedly the extreme instance of such experimentation. The methods themselves don’t change; he trusts them too much to monkey with those cogs and pulleys.

He tries to find out just how far he can push his style—a style that at its most basic is all about flash cards, quick cues, attention-getting gags. Will it see him through a region of fluidity, ominous depths, reverie, inchoate yearning? In Vertigo, faced with a novel problem of exposition—to show, in pictures, how an emotional complex forms—he proceeds as methodically as when working out a chase or a murder scene. Applying the same kind of storyboard logic, he breaks down the gradations of an emotional trajectory into elements that can be laid neatly side by side like painted tiles, just like those shots of the falling wine bottle.

That is precisely where the strangeness comes in: the diagrammatic qualities of Hitchcock’s art are enlisted in the service of what cannot be diagrammed. Vertigo charts an emotional progression almost outlandishly gorgeous in the unfolding of each of its stages—gorgeous like some bright guidebook to magic hotels and highways—concealing until nearly the end that it can only terminate abruptly and cruelly. The perfect equilibrium which marks each phase makes all the more brutal the imbalance in which the process unavoidably culminates.

He has designed a beautiful trap. The weird poetry of it resides in the Spanish filigree, the tombs and castanets and ancestral portraits, the ritualistic moves suggesting a Calderón drama or some odd baroque poem secreted in a California monastery, at once florid and elaborately logical.

To allow yourself to be alienated from this spectacle is to see a mechanical contraption of arranged flowers, curled hair, carefully directed lighting: like nothing so much as a funeral home. The lovers look like cutouts (to harmonize with the out-and-out animation of the nightmare scene), or like the figures on cheap tin paintings of saintly miracles or deathbed conversions: waxen, painted, mummified dolls.

But the toys are set in motion. Everything is swirling, tilting, swinging like the hypnotist’s pendulum, teetering as in the middle of a small earthquake. The spirals multiply as if in a toy shop full of mirrors and kaleidoscopes, from the whirling of Gavin Elster’s swivel chair to the wave in Madeleine’s hair. People are perpetually crouched or perched on the edge of imbalance.

Vertigo epitomizes, even as it surpasses, the sensual pleasures of Fifties movies: wide screen and color allied to deep focus, monumental boom shots, smoothly gliding camera movements. We are guided through a hall of glamorous surfaces. Scottie’s bachelor den, with its fireplace and coffee, its comfortable furniture and companionable television set, provides the perfect setting for The Man Who Reads Playboy to realize his ultimate fantasy, finding Kim Novak as Madeleine deposited magically in his bed. The implied cheap thrill—Scottie’s undressing of the unconscious Madeleine, indicated by her nylons hanging in the kitchen to dry—still gets a titter from audiences, as does his subsequent sheepish admission that he’s enjoyed himself.

It’s the only point at which this ethereal romance gets down to earth at all. As Scottie and Madeleine are flirting outside his apartment there’s a moment when they behave almost like normal Hollywood stars undergoing a plot turn in a romantic comedy. At that instant they radiate an unattainable desirability denoted by the utterly unreal colors of Robert Burks’s cinematography: the otherworldly cosmetic sheen of Movie Love.

That was the moment when, at age fifteen, I decided that it mattered a great deal to me whether Scottie and Madeleine succeeded in establishing a full and satisfying union. Not to care is to remain immune to the lure of Vertigo. Hitchcock’s gamble is that the spectator will take the bait and allow the movie to tease out his intimate concern for the fate of these beings.

Right from the start of Saul Bass’s opening titles—the woman’s face in darkness, the eyeball, the spinning geometric shapes, the revolving phrases of Bernard Herrmann’s theme—the effect is deliberately hypnotic. The tonal control exercised by Hitchcock in all his films here attains a new degree of thoroughness. We enter a world from which all superfluous detail has been removed as if surgically, with none of the intrusions of spontaneous movement.

Controls are exerted at every level. Tone of voice, for instance: the line readings establish a languorous, not to say somnolent, hum. That the voices are never raised in emotion until the final scene (except for the outburst of poor discarded Midge, alone in her room) contributes to an air of hermetic intimacy.

Almost all actions in Vertigo are commonplace: sitting at a bar, driving a car, drinking coffee at home, walking, talking in low civilized tones, looking intently but with no melodramatic staring. If not for the strategically timed falling of bodies (the cop from the roof, Novak into the bay and twice again from the tower), these could be scenes from anyone’s life, the very antithesis of Hitchcockian adventure.

The multiple play of glances in the socially complex situations of movies like Notorious, The Paradine Case, and Strangers on a Train is simplified here: there are no nuanced interactions among groups of characters because there are no groups of characters. Indeed, beyond Stewart and his wraithlike love there are in effect no characters except for Barbara Bel Geddes as Scottie’s long-suffering former girlfriend Midge, without whom there wouldn’t even be anyone to witness the drama. Most scenes involve only two people. In effect there is no society: no children, no parents, no parties. Each person follows a solitary track.

Minor characters exist only to irritate, to intrude on Scottie’s solitary contemplation of his dream lady. Especially the women: the hotel clerk who questions Scottie’s authority, the neighbor who asks prying questions about Madeleine’s suicide, the saleswoman and the hairdresser who seem to take intuitive pleasure in frustrating Scottie’s impatient desire to remake Judy as Madeleine. For that matter Midge herself is the ultimate intrusion as she tries to hold him back from plunging into the vortex. (Stewart superbly suggests the resentment with which he withdraws from her attempts at companionship, as if to say, “Leave me alone, I’m only trying to destroy myself.”) Of all these subsidiary ushers and go-betweens, the only one who exists with any vividness is Henry Jones as the presiding judge who at the post-mortem inquest skewers Scottie for his alleged irresponsibility in letting Madeleine die; Jones’s brilliant monologue, almost too calculating in its cruelty to qualify as comic relief, marks the division between parts somewhat like the porter’s speech in Macbeth.

There is San Francisco, of course, but the city seems to exist behind glass or under water. Hitchcock favors stuffy interiors like Gavin Elster’s overfurnished office and terminally muffled club room, with their expanses of dark leather and paneled wood, shelves of glassware, framed hunting prints. San Francisco appears to be a city of the dead, or at any rate a city in suspended animation. There is no action on the street, no trace of spontaneity to offset the funeral march of Stewart’s obsessional progress: just a ghostly procession of cars and bodies, set to mournful music.

It’s like being in church, a church in whose dank precincts all desire is somehow entombed. The only moment when strangers are endowed with any independent life is in a fleeting shot of lovers embracing on the grass in Golden Gate Park as Stewart and Novak (in her second incarnation) walk by. Those anonymous lovers seem to be the only ones having fun in the whole bewitched city.

The prodigal richness of Vertigo—the system of visual rhymes and musical leitmotifs, the bold chromatic range from misty green to strident purple, the incredible variety of locations providing each shade of feeling with its own distinct habitat—is matched by a poverty at its core, a resolute slamming shut of anything that would provide an exit or an opening. The spiral is sealed off within its coiling.

Two utterly schematic figures stand guard to ensure that the melodrama cannot be evaded. First of all the villain of the piece, Gavin Elster, an absurd stick figure with a moustache and a fake accent, is the sole author of the crime around which the movie revolves, and a personage of so little account that we don’t even learn his fate. He’s a flat silhouette standing in for all those seductive and malevolent men—jovial spies, homosexual doubles, psychopathic shadows—delineated elsewhere more fully, indeed with something like compulsive precision, most particularly by Joseph Cotten in Shadow of a Doubt.

Likewise the nun who rises out of the dark stairwell to accidentally cause Kim Novak’s second death is the shorthand encapsulation of that band of females who poison the atmosphere of countless Hitchcock films (the scheming housekeepers like Mrs. Danvers in Rebecca and Millie in Under Capricorn, the domineering mothers of Claude Rains in Notorious and Anthony Perkins in Psycho and Tippi Hedren in Marnie). This one doesn’t even need a name: all she has to do is emerge to precipitate disaster.

They stand, as it were, at the exits. All the rest of space and time belongs to Scottie and his bisected love-object Madeleine/Judy, the socialite and the shopgirl, neither of whom seems able to make the hero altogether happy. His love will lure him to destruction, the oldest story: except that here it’s told differently from all the other movie versions. It isn’t the professor and the floozy, the barrister and the fallen woman, the sailor and the jungle princess.

The mysterious woman in Vertigo is not a femme fatale because, with the exception of the unseen Rebecca, there are no femmes fatales in Hitchcock. Barely a single manipulative beauty or scheming temptress, in genres (the spy film, the murder mystery) unthinkable without them. With Hitchcock the figure of the femme fatale appears only obliquely. Ingrid Bergman in Notorious, like Eva Marie Saint in North by Northwest, is merely mistaken for one, while Marlene Dietrich in Stage Fright, Laura Elliot in Strangers on a Train, and Brigitte Auber in To Catch a Thief are respectively theatrical, provincial, and adolescent imitations of the type. Even Alida Valli as the beautiful murderess in The Paradine Case doesn’t really qualify: she’s too emotionally honest, too genuinely repulsed by Gregory Peck’s obsession with her.

This in a way is Hitchcock’s problem; everything would be simpler if he could settle for Maria Montez as the evil twin in Cobra Woman or Lizabeth Scott coldbloodedly committing murder in Out of the Past. But perhaps that is why he doesn’t make the same movie that all the others do. He has other obligations, to a trim, well-groomed society woman, the sort who dines at Ernie’s and shops at Ransohoff’s and is a regular client of the most expensive florist in San Francisco. Madeleine’s conversation is hardly imaginable; if it weren’t for her nightmares and suicidal impulses, she would have nothing to talk about. She’s barely there apart from her wardrobe.

If he cannot explain coherently why she means so much to him, the director will do better: he will put the spectator in a position where he cannot help identifying with the director’s feeling. Was it finally only for this that the whole mechanism was set in motion, that we might be brought to share Hitchcock’s deep concern for these particular shoes, this particular hairdo, this particular elegantly tailored gray suit? So that he might not be altogether alone in a desire which will accept no substitutes?

No one watching Vertigo ever doubts that the director is in love with Madeleine. He makes his feelings sufficiently clear. The cinematic device Hitchcock invented for the film—the simultaneous tracking back and zooming in which denotes the flare-up of Scottie’s vertigo—is the filmic equivalent of a neologism coined because one feels that no existing word can adequately express one’s feelings. It’s that desperate and flailing a gesture: a calligraphic representation of energy collapsed on itself and banging back and forth within its confines.

It may be that Vertigo is a movie best appreciated by the young and virginal; certainly it is the most chaste movie ever made about erotic obsession. The famous 360-degree pan around the embrace of Scottie and the resurrected Madeleine, amid the crescendoing of Bernard Herrmann’s indelible “Scene d’Amour” theme, manages to turn lovemaking into an altogether abstract notion. A fifteen-year-old can still experience the movie as a sublime romantic dance on the edge of nothingness, while with age it more and more suggests dissatisfaction, blocked yearning, a systematic and most unhappy discomfort. In her memoir of growing up obsessed with the film, Louise DeSalvo writes of herself at sixteen: “I know I don’t want to wind up like Scottie, in love with death…. Each time I see Vertigo, I move closer to learning that loving someone the way Scottie loves Madeleine is dangerous.”

So dangerous that when he does meet her double he doesn’t have much steam left for fresh experience. This is the point at which the movie starts from the beginning again, this time not as tragedy but as compulsive routine. The romantic project of rescuing the doomed maiden from death gives way to the fetishist’s laundry list of required elements: shoes, check; fabric, check; wave in hair, check. The film’s sustained adagio snaps into a different rhythm as the hero assumes the role of overt control freak, fetishist metteur-en-scène energetically commanding resources of light and color and shape. Stewart’s veneer of sensitive caring for his precious object cracks whenever she makes the slightest objection to his makeover, revealing a brusque impatience. This is the most remarkable aspect of a performance extraordinary for its shifts of tone; consider the rough way he passes Judy a slug of whiskey when she starts to complain, and how casually it undercuts the mood of ostensible tenderness.

As for Judy Barton from Salina, Kansas, the real woman, there just isn’t enough time to develop any genuine concern for her. (She has one of the great reductive lines of dialogue: “My name is Judy Barton, I come from Salina, Kansas, I work at Magnin’s, and I live here.”) That would be another movie, another life. We are left with the unforgettable awkwardness of Scottie and Judy dancing close at the start of what promises to be an uncommunicative but nonetheless real enough relationship, unlike all that nonsense with the lady in grey.

It is a movie from which one yearns in the end to be delivered, as from an incubus or an ancestral curse, precisely because such deliverance is not an option within the closed circle of Vertigo. It took all Hitchcock’s skill at neat resolutions to create so artfully a setup without a resolution. Where in Foreign Correspondent or North by Northwest the audience is led along by the question, How will they ever get out of this? the course of Vertigo encourages a growing sense of dread at the insurmountable difficulty, and eventually the impossibility, of finding any way out. Not merely is there no happy ending, there could never have been one; she who could have brought it about no longer exists; never in fact existed.

Hitchcock has here made a diagram of chronic corrosive sadness. Only at the end is it clarified that the film has been in mourning from the first, has been grieving from before the start for the ending which was already a foregone conclusion. The only consolation his art affords him is to have bodied forth, without compromise or alleviation, the figure of James Stewart staring downward (after his beloved’s second and irrevocable death) into emptiness, unconsoled in eternity.

This Issue

December 19, 1996

-

1

Arthur C. Danto, After the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History (Princeton University Press, to be published next month). ↩

-

2

Victor Burgin, Some Cities (University of California Press, 1996). ↩

-

3

Louise DeSalvo, Vertigo (Dutton, 1996). ↩

-

4

François Truffaut, Hitchcock (Simon & Schuster, 1967). ↩

-

5

Quoted in Robert E. Kapsis, Hitchcock: The Making of a Reputation (University of Chicago Press, 1992). ↩

-

6

The cold war figures belatedly in Torn Curtain (1966) and Topaz (1969), but these are far from typical. ↩