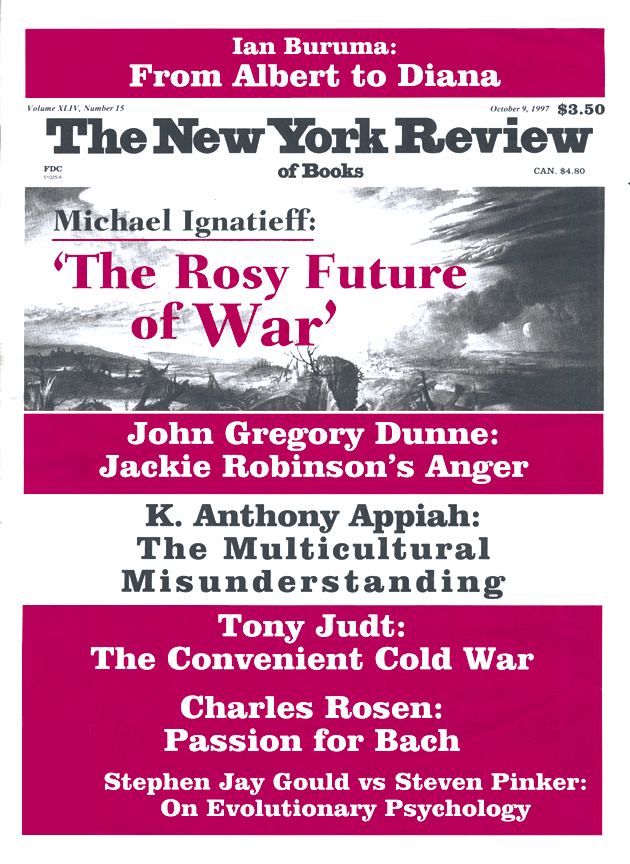

Once again a British queen was accused of remaining selfishly in Balmoral. “Come out and cry with your people!” the British tabloids screamed in the week after Diana’s death, when the House of Windsor was holed up in the Scottish Highlands, while Diana fever mounted everywhere else. And the Queen came down to London, and she looked stunned by what she saw.

The life and death of Diana, Princess of Wales, were full of peculiar echoes of the past. But the similarities were like jokers in a reshuffled pack of cards: they looked the same, but were all in different places.

Parallels with Prince Albert are perhaps the most obvious. Like him, Diana Spencer was taken into the royal household to breed. And like Albert, Diana ended up transforming the image of British royalty, though in an utterly different way. As a tireless do-gooder Albert did far more than Diana could in her short life. But she had her grand moments. Her embrace of an AIDS patient in a hospital ward was one of the most touching, and well-publicized, of them. Like Albert, she sensed that the royal family, to survive, cannot rest on ceremony.

But the differences between Diana and Albert were more interesting. There was a subtext to Diana’s battle with the Windsors. Not everyone expressed it as crudely as the British pop journalist Julie Burchill, who constrasted Diana’s fresh, spontaneous, honest “Englishness” with the “gothic gloom” of the “Graeco-Germans” in the House of Windsor. But the Englishness of Diana, the very aristocratic “English Rose,” was certainly a mark in her favor, just as the German ancestry of the Windsors is never entirely forgotten. In this sense, Diana, the outsider, is really the insider, a status Albert could never have hoped to acquire. Nor could he have shared her plight as the wronged wife in a love-less marriage. But he might have sympathized; it was what happened to his own mother—and millions of other women who now worship Diana.

The other big difference can be summed up in one word: charisma. Where Albert was dull, earnest, and plodding, Diana sparkled. The “domestic monarchy,” that faux-bourgeois guise started by Victoria and Albert, and perfected by the present Queen, was perhaps destroyed forever by Diana’s success as a global media celebrity. Her status was based on royal mystique, but then boosted out of all proportion by every means available (yes, including paparazzi) to the international celebrity industry. Diana was the first movie star never to act in a movie, the first rock star never to play in a band.

Hers was an extraordinary act, full of guile, as well as naiveté, self-indulgence, as well as some genuine generosity. There is a fundamental difference, however, between the celebration of stardom and the deference to monarchy. The latter is based on secrecy; the mystique only works if the private is shrouded in mystery. Stardom, on the other hand, explodes the borders between public and private. The stars, whose “lifestyles” are endlessly flaunted in our faces, whose love lives hold no secrets, whose opinions and, above all, feelings are always “shared” with their fans, belong to us, the consumers of global media gossip.

By turning herself into a star, Diana managed to defy the House of Windsor, which she saw as her enemy, and created a very modern fairy tale: the royal celebrity, Diana, Princess of Vanity Fair. When her act ended in death, this global media event released much older, primitive, religious emotions. The image of Diana’s face, fading at the end of the BBC broadcast of her funeral service, had the kitschy pathos of a Marian cult. Her impact on British life is now undeniable, but she remained to the end a rather camp Madonna. I don’t know what was more remarkable: the tawdriness of her fairy tale, or the infinite capacity, even of the most intelligent people, to believe in it.

—September 11, 1997

This Issue

October 9, 1997