In response to:

Life & Death on the Social Ladder from the July 16, 1998 issue

To the Editors:

How can Helen Epstein [NYR, July 16] think it is implausible that societies with narrower income differences have better health, but plausible that more cohesive societies are healthier? She appears not to have read my replies to critics of the income distribution part of the argument or to know that there are now some 20 papers testifying to this relationship and only two which fail to confirm it—both using data from the same source (see http://weber.u.washington.edu/~eqhlth/). If the international evidence provided in my Unhealthy Societies: The Afflictions of Inequality is flawed, how come that it has led to tests which dramatically confirm the relationship within the USA? Not only are the more egalitarian States healthier, but the same relation holds among 282 Standard Metropolitan Areas and among counties. This relation, found among blacks and whites, is not explained by differences in average incomes, absolute poverty or smoking.

It is explained by the quality of the social environment. In the rich countries poor health and numerous other social problems reflect the damage done to the social environment by economic inequality. Thus there is a close relation between greater income inequality and low levels of trust, higher hostility, and—as some 34 studies attest—higher rates of homicide and violent crime. In his study of the Italian regions Putnam notes that his index of “civic community” is highly correlated with income equity and says that an egalitarian social ethos is “an essential feature of the civic community.” In short, income distribution serves as a measure of the burden of relative deprivation and its social consequences.

Richard G. Wilkinson

Professor of Social Epidemiology

University of Sussex

Brighton, England

To the Editors:

Helen Epstein’s article, “Life and Death on the Social Ladder” [NYR, July 16], deserves commendation because in her review of the books by Wilkinson, Karasch and Thorell, Sapolsky, and Wolf and Bruhn, she makes it clear that those who today are at the lower end of the social scale suffer from coronary heart disease more frequently than those who are at higher levels.

But this difference was not so at the beginning of this century. William Osler, still considered America’s most distinguished clinician, remarked that in his entire career at Johns Hopkins (extending over several decades, 1890-1910) he encountered only six cases of coronary disease in the charity patients at this hospital.1 But he saw many patients with this disease in his consultant practice. The majority of these latter patients were physicians—particularly those who indulged in commercial activities in addition to their practice of medicine.

The chief characteristic of these upper- class coronary patients of Osler was their possession of what Osler described as an “indicator whose engine was always at full speed ahead.” So obvious was the speed of their walking and talking that Osler opined that he could usually diagnose their possession of coronary disease as they entered his consultation room.2

Why has this relative immunity to coronary artery disease in the poverty class of an earlier day diminished? I believe that it has done so for the same reasons that it has done so in Wolf’s and Bruhn’s contemporary inhabitants of Roseto in just a few decades. The Rosetans, now like those of the lower social/economic groups today, find themselves oppressed by a growing sense of insecurity due to an increasing loss of family and friendship ties as well as waning numinous supports for which the motor car, the radio, television, and the Internet cannot substitute. Also, a feeling of hostility toward their superiors has supplanted what in earlier decades was a certain awe or esteem for those in superior positions. In our own studies, we have found that approximately 65 percent of corporate vice presidents, managers, and employees harbor hostility toward their immediate superiors. Moreover, one of the reasons for this hostility is that by television, newspaper, and magazine, the foibles, including greed, of many of the corporate elite are increasingly exposed to the lower classes so their former admiration and esteem of their superiors is giving way to hostility and contempt. For example, The New York Times Weekly reporting on June 22, 1998, the firing of Mr. Dunlap, the CEO of the Sunbeam Corporation, stated, “Many of Mr. Dunlap’s former employees and associates unapologetically celebrated the public way in which he was thrown into the ranks of the unemployed.” The Times also reported that Mr. Dunlap became known as Chain Saw Al for the way “he downsized thousands of workers while earning millions of dollars for himself.”

As if this bit of news was not enough to increase the contempt and hostility of those on the lower socioeconomic ladder, The Times on the same page reported that Mr. Gus Levy, a former chairman of Goldman Sachs and Company, once described the firm’s secret of success as “long-term greedy.” The Times added that the 190 partners of the same firm had decided to dissolve their partnership in favor of selling shares to the public and reaping as much as 30 billion dollars. This bit of news suggesting that 190 partners may each receive over 30 million dollars adds to the growing hostility of the have-nots against the haves.

Besides this growing hostility of those on the lower rungs toward those higher on the ladder, there has been a remarkable increase in the sense of impatience that by no means has spared the lower socio-economic classes where deadlines (often imposed upon them) have become a way of life for them.

This sense of time urgency or impatience and easily aroused hostility are the two components comprising Type A behavior which now oppresses Western society.3 In short, Epstein in correlating incidence of coronary artery disease to the rung one occupies on the social scale might well recognize that the intensity of one’s impatience and hostility (precursors of premature incidence of coronary heart disease) is greatly influenced by one’s socioeconomic status. Both Stuart Wolf and Robert Sapolsky, whose books Epstein reviews, have recognized and supported the relevance of this type of behavior to coronary heart disease.

Meyer Friedman, M.D.

Meyer Friedman Institute

UCSF-Mount Zion Medical Center

Helen Epstein replies:

I agree with Richard Wilkinson that social factors may be important for population health, but the relationship between population health and economic inequality is as yet unproven and may even be impossible to prove. The studies that suggest such a relationship are ecological, that is, they measure relationships among variables in whole populations, not in individuals. These sorts of studies are prone to error and their conclusions, while often suggestive, cannot be taken as proof. Other interpretations are always possible. Porsches, diamond necklaces, and washing machines, like economic equality, could probably all be shown to correlate with population health. This does not mean that these things necessarily, by themselves, save lives in the same way that getting people to quit smoking and lower their cholesterol saves lives.

Inequality in some of the former Communist countries of Central Europe, such as Poland and the Czech Republic, is now soaring. At the same time, life expectancy in these countries is rising faster than it has in decades. Social factors, along with improvements in diet and reductions in smoking, may have something to do with these gains. Income inequality probably doesn’t.

Meyer Friedman’s letter raises some interesting points. There may well have been higher rates of coronary heart disease (but not heart disease in general)among professional people than among laborers and the poor at the beginning of the century. However this is controversial. (See G.D. Smith, “Socioeconomic Differentials,” in A Life Course Approach to Chronic Disease Epidemiology edited by D. Kuh and Y. Ben-Shlomo [London:Academic Press, 1997].) Osler worked on coronary heart disease in the decades when it was first being described and diagnosis was not as consistent as it is today. Doctors who treated well-to-do patients may have more readily diagnosed the condition than those who treated poorer ones. If coronary heart disease really was once more common higher up the social ladder, the reasons for this, and for why it is now more common lower down, are not clear, although there are many theories about it.

Hostility may well play a role in coronary heart disease, but it is unlikely to be a primary actor. Rates of coronary heart disease have fallen by around 70 percent in the US since the 1970s, and they have lately been falling throughout Europe as well. Have we all become more serene? Other indicators, including rising rates of divorce, assault in the workplace, and road rage, suggest not.

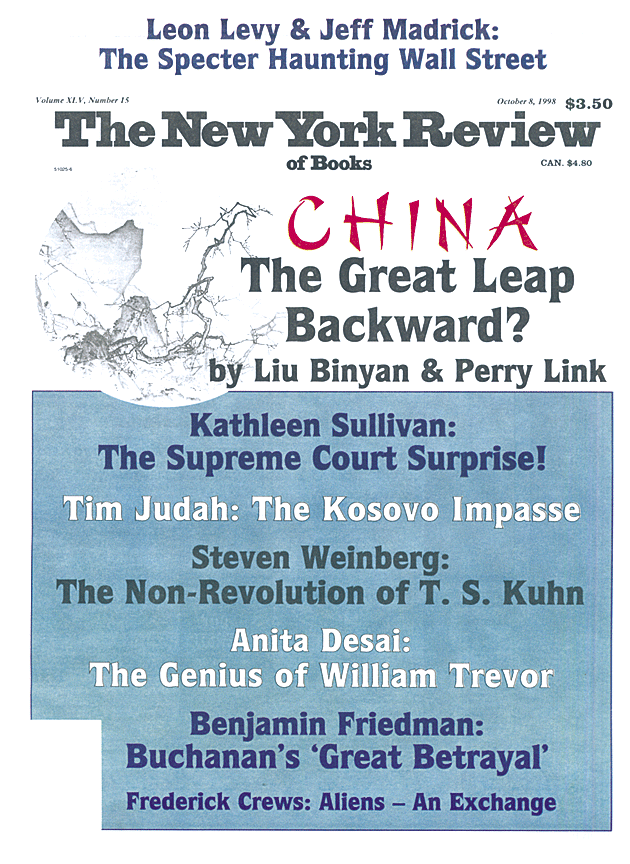

This Issue

October 8, 1998

-

1

W. Osler, The Lumleian lectures on angina pectoris, Lancet, 1910, 1:839. ↩

-

2

W. Osler, The Principles and Practice of Medicine (New York: D. Appleton &Co., 1892); W. Osler, Lectures on Angina Pectoris and Allied States (D. Appleton & Co., 1897). ↩

-

3

Meyer Friedman and D. Ulmer, Treating Type A Behavior and Your Heart (Knopf, 1984); Meyer Friedman, Type A Behavior: Its Diagnosis and Treatment (Plenum Press, 1996). ↩