The kings of Tin Pan Alley—Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern, George Gershwin, and the rest—were a collegial but competitive bunch. Quick to praise each other’s music and to pay one another generous formal tributes, they dined together, played cards together, occasionally vacationed together—but always kept a sharp eye on the sales figures, their own and their rivals’.

Something of this friendly, feisty spirit seems to have permeated much of the writing about them. In biographies and theater reviews, in album liner notes and reminiscences, one is forever coming upon rankings and hierarchies: who was the best songwriter, and who the next best, which were the five finest musicals, the ten all-time greatest ballads. This is the domain of aficionados, and categories rapidly ramify into subcategories: the best bar songs ever written, the finest torch songs, the cleverest list songs…

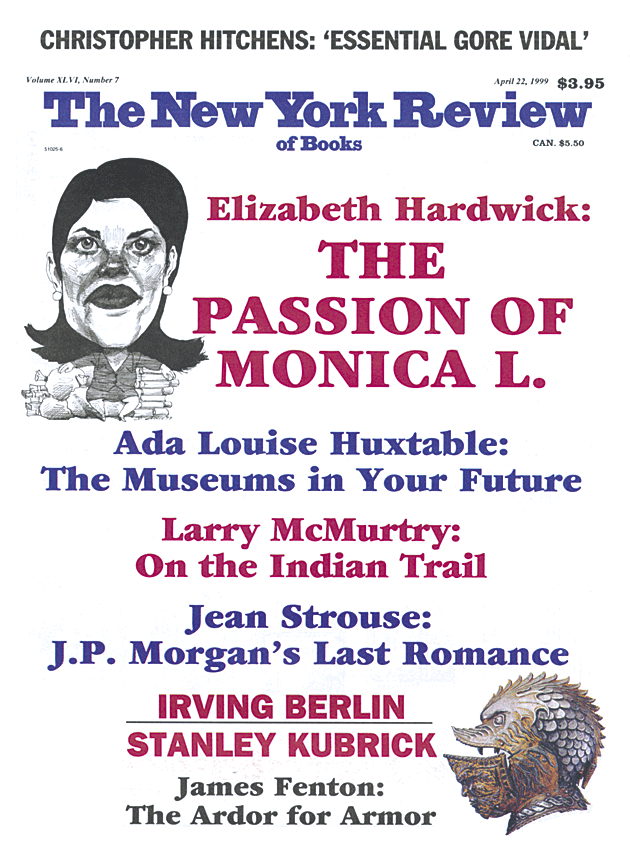

But even among people keen for argument, there’s little dispute over who enjoyed the most remarkable life. What could be a more implausible, inspiring tale than that of Irving Berlin, born in 1888, who sold the rights to his first song for thirty-seven cents and went on to triumph, in his hundred-and-one years on the planet, in one musical revolution after another? More than half a century elapsed from his first hit, “My Wife’s Gone to the Country, Hurrah! Hurrah!,” in 1909, to his last Broadway show, Mr. President, which closed in 1963. (George Gershwin, by poignant contrast, was dead at the age of thirty-eight, felled by an undiagnosed brain tumor.)

Berlin launched his career in raucous Lower Manhattan, in an age when songs were boosted through “song-pluggers” in bars and theaters and stores, and hits were measured in the currency of sheet music; he plugged away as fervently as anyone, tossing off hit after hit, and became a partner in a firm of musical publishers by the age of twenty-three. When the rise of radio eclipsed the sheet music business—when a family no longer needed to perform a song themselves in order to bring it into their home—Berlin dominated the airwaves. When movies learned to talk and sing, he ventured out to California and, in a pair of Astaire-Rogers films, lifted the Hollywood musical to heights never since surpassed. He was still a commanding musical force—advance sales for Mr. President were a then-unprecedented two-and-a-half-million dollars—on the eve of Beatlemania.

There’s a pleasing irony to the notion that the man who became our nation’s unofficial songwriter laureate (the creator of, among other things, “God Bless America”) wasn’t born in this country—and a second appealing irony to the notion that his family origins were so misty. He might have sprung from Anywhere, Foreignland. No one in the family seemed to recall precisely where the Berlins had variously originated—“back in Russia” was about all that was certain. (Berlin’s daughter Mary Ellin Barrett reports, in her appealing account of her parents’ marriage, Irving Berlin: A Daughter’s Memoir, that “latter-day research…indicates that my father was probably born in western Siberia.”) To complicate matters, the Berlins weren’t the Berlins when they disembarked on Ellis Island, in 1893, but the Balines: Moses Baline, a forty-six-year-old cantor, his wife Lena, and six children, the youngest of whom was five-year-old Israel. Before remaking the popular music of his adopted country, Israel Baline would remake himself, first name and last.

Moses never prospered in his new homeland—he became a part-time kosher poultry inspector and housepainter—and the family was still living in close-quartered sweatshop poverty when he died in 1901. Israel/Irving was thirteen. Moses, dogged by failure, must have sought consolation in the new opportunities he’d given his children. But even had he lived a few more years, Moses couldn’t have felt too sanguine about his youngest child: a slight, ragged boy who, despite having no formal musical training and an inability to read music, despite a thin tenor voice and extremely primitive skills on the piano, had resolved to pursue a musician’s life. More pathetic still: this high school dropout was composing his own lyrics. Shortly after his father’s death, Irving left home—“went on the bum” was his phrase—and apparently, although documentation for this portion of his life remains patchy, spent some two years living alone in lodging houses, singing in Bowery saloons, and taking what odd jobs he could find.

Later, Berlin married twice, both times to Gentiles. His first wife, Dorothy Goetz, sister of one of his collaborators, died in 1912, five months after their wedding, her health undermined by typhoid fever contracted during their Cuban honeymoon. Berlin waited fourteen years to remarry, this time to Ellin Mackay, daughter of Clarence Mackay, whose Irish-Catholic emigrant father, John “Bonanza” Mackay, had been a Nevada silver baron and one of the wealthiest men in America. Within a generation, entrance into the aristocracy had been purchased by the Mackays, so that when Edward, the Prince of Wales, visited America in 1924, one of his dinner-party stops was the Mackay home on Long Island, where he sat beside Ellin and afterward danced with her.

Advertisement

The Mackays were elevated people. Of course Berlin, too, was climbing quickly, in his fashion: by the time he met Ellin, in 1924, he’d become a perennial, internationally famous hit-maker. Their “mixed marriage”—as the press of the time would have it—captured the fancy of the world. They eloped and sailed to Europe, without the approval of Ellin’s father.

Berlin composed a song for Ellin at this time, “Always,” whose lyrics hummed with all the customary hyperbole of the songwriter’s trade:

I’ll be loving you, always,

With a love that’s true, always.

When the things you planned

Need a helping hand

I will understand, always.

Yet the pledge wasn’t empty. The marriage endured for sixty-two years, until Ellin died of a stroke when Irving was one hundred. During those sixty-two years there’s no record of his ever forming an attachment to another woman.

Not surprisingly, Berlin’s life has attracted its share of biographies, the first of them appearing when he was only thirty-six. In recent years we’ve had Lawrence Bergreen’s big, comprehensive, well-received As Thousands Cheer: The Life of Irving Berlin in 1990, followed by Mary Ellin Barrett’s memoir in 1994. The newest are Edward Jablonski’s Irving Berlin: American Troubadour, Philip Furia’s Irving Berlin: A Life in Song, and Charles Hamm’s Irving Berlin: Songs from the Melting Pot.1

It’s hard to figure out what motive propelled Mr. Jablonski’s book—other than the urge to write another book. (His “also by” page lists twenty-three titles.) He doesn’t come close to matching Bergreen’s considerable strengths: depth of background, balance of portraiture, believability of motivation, richness of peripheral detail. Nor does he seem intent on amending Bergreen’s occasional shortcomings: the clumsiness of his musical descriptions, his credulity, the traces of something hasty in his fact-checking (he repeats the familiar but unfounded tale that Berlin bailed out his father-in-law during the Depression with a million-dollar check; misidentifies the island from which the Enola Gay departed for Hiroshima; misleadingly implies that Richard Rodgers began collaborating with Hammerstein only after Hart’s death; etc.). Jablonski has almost nothing to say about the final decades of Berlin’s life—he accords a mere eighteen pages to his final twenty years—which were a bleak but psychologically revealing period, as Bergreen convincingly shows. (Jablonski is spared, however, Bergreen’s unwittingly comic obsession with weight, which leads to constant reminders that someone should have shed a few pounds: “the obese critic complained,” “the rotund director breathed an enormous sigh of relief,” etc.)

Furia lays the life out clearly and compactly, and gives Berlin his welcome due as a lyricist, as well as a composer. But the book is short on psychological penetration—nothing like a complex man emerges from its pages—and you might say that Berlin went on and outlived his biographer: Furia’s energies, like Jablonski’s, appear to flag well before his subject’s sprawling life concludes, and Berlin’s last forty-plus years—which include a number of Broadway shows, the debacle of Mr. President, and the death of his wife—are crammed into thirty pages.

Actually, my favorite Berlin anecdote—the one that best conveys the man’s intense, impacted presence—comes from Barrett’s memoir. Her mother, Ellin Mackay, describes a moment of misgivings as she readies herself to marry Berlin—knowing that by doing so she will painfully estrange herself from her adoring but anti-Semitic father and will work a permanent breach with many of her high-society friends:

I remember once catching this sudden glimpse of him standing under a street lamp. He had a hat on I didn’t much like, and he was chewing gum. As he chewed, his hat moved. I thought, Is he really what I am ready to give up all for, this funny little man chewing gum with his funny hat that moves as he chews, up and down, up and down on his head?

The image captures Berlin with a caricaturist’s slashing exactitude: the unease; the fidgeting energy; the hints of a boorishness that would keep him an outsider, however much money he amassed, among certain rarefied social circles; and, in its underlying devotion, the sense of some unaccountable specialness to the man—something as unlikely and as transformative as genius.

Whatever you want to call it—genius, a flair, a gift—something about Berlin’s talents has always awed and daunted his critics. Partly this is a simple matter of sales figures. Nobody wrote more hits, bigger hits, longer-lived hits than Berlin. (Bing Crosby’s rendition of “White Christmas,” with estimated sales at thirty million, sits securely lodged in The Guinness Book of World Records.) Late in life Berlin declared, “You can’t sell patriotism, unless the people feel patriotic. For that matter, you can’t sell people anything they don’t want.” No other songwriter so often, and over so many years, sold the American public what it wanted.

Advertisement

Yet the sales figures do not so much explain as deepen the puzzle. In both melodies and lyrics there’s a directness to Berlin’s compositions, a made-to-order quality, that logically ought to lead to formula and flatness—but doesn’t. Berlin’s career vindicates Harold Arlen’s observation that simple songs “are the hardest to write.” Somehow Berlin repeatedly managed to “give them what they ask for” in a straightforward but beguiling fashion. During the writing of Annie Get Your Gun, he was urged to compose a “challenge song”—a tune in which Annie Oakley and her beau Frank Butler could indulge in some one-upmanship—and fifteen minutes later Berlin produced one of the great joys of the show, “Anything You Can Do.” Need a sentimental song for the holidays? Maybe something called “White Christmas”… A patriotic song for an Armistice Day broadcast? Perhaps “God Bless America”… A pledge of eternal devotion? Why not “Always”…

In their choice of subject matter, most popular songwriters are essentially lyric poets: they have a small range of themes—most of them revolving around romantic love—which are systematically ransacked in an endless search for novelty and vibrancy. Berlin, however, was a novelist by temperament: his goal was comprehensiveness, the scattered daily minutiae of life. He meant to turn the full range of the American experience into song: everything from life in the military to national holidays, from dance crazes to ethnic assimilation and humor, from political campaign songs to Depression joblessness.

There’s a mystery to Berlin’s songs—time and again a deeper interest, a greater catchiness, than a first hearing suggests. In his authoritative American Popular Song, Alec Wilder, after declaring himself “frankly astounded” by Berlin’s sophistication, asks with delighted wonder, “Where does this man find these tunes?” Gary Giddins, in his new Visions of Jazz, says of Berlin’s accomplishment, “the more closely you scrutinize it…the more miraculous it seems.”2 I suspect my own experience of listening to Berlin over the years is quite typical. With other songwriters, I feel confident about dismissing what I don’t like after a couple of hearings. I feel quite certain I never need listen again to Rodgers and Hart’s “Way Out West” or Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “Edelweiss,” Hoagy Carmichael’s “Hong Kong Blues” or Yip Harburg and Harold Arlen’s “Little Drops of Rain,” Cole Porter’s “Don’t Fence Me In” or “True Love.” With Berlin, though, judgments feel less secure. I’d always thought “Easter Parade” was a song only a child could love—until I heard Billy Eckstine and Sarah Vaughan’s recording. And I’d thought “All Alone” a lugubrious throwaway until I heard Dinah Shore do it. Who knows? Maybe I’ll one day find myself enjoying “White Christmas”…

“The mob is always right,” Berlin propounded as his credo. Not for him the solace of being an unsung genius. If a well-promoted song failed to sell, this could mean only one thing: it wasn’t all it was cracked up to be.

Mob rule? Mob taste? Berlin’s credo sounds like a blueprint for cultural disaster—a world in which pandering artists cater shamelessly to a pap-fed public. That it didn’t turn out disastrously testifies to something wonderfully sure-spirited about America in those years when, between the two world wars, Tin Pan Alley enjoyed its golden age. Not surprisingly, it was the era of another equally improbable American triumph: the never-since-equaled scintillation and charm of the Thirties’ screwball comedies.

When you examine a list of Berlin’s lesser-known songs and outright failures, they sound like exercises in opportunism and cynicism. Need a song about Anglo-American amity as the two nations contend with Hitler? Here’s “My British Buddy.” A song to celebrate the founding of a Jewish State? “Israel.” Even a song to reconcile us to the IRS? “I Paid My Income Tax Today.” And yet Berlin remained uncynical. He wielded a public responsibility, believing as he did that music was far more than mere entertainment: “Yet music is so important. It changes thinking, it influences everybody, whether they know it or not.”

In his self-assured moments, he not only knew his own value but believed wholeheartedly that it reflected a greater, a public validity: “A good song embodies the feelings of the mob and a songwriter is not much more than a mirror which reflects those feelings.” He also believed in the ongoing improvement of musical taste: audiences are “getting wiser every day regarding the caliber of songs [they] desire.” He advised his fellow songwriters to circulate in the lobby after one of their shows, to rub elbows with the departing audience and “watch what they’re humming.” He doesn’t appear to have questioned the fairness or wisdom of the mob’s judgment. That wasn’t his job, after all. He was no critic, thank heavens (a “stupid and pretentious” business—mostly “a lot of crap”). His job was to create likable, worthy songs—and when the mob balked at something he offered, he came back at them with another selection. Time and talent were on his side, after all: he had hundreds and hundreds of tunes in his head.

As various critics have pointed out, he was an original from the outset: “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” (1911) has been called the first successful pop song with two keys; “When I Lost You” (1912) the first modern love ballad; Watch Your Step (1914) the first Broadway score by a single composer. These are the sorts of claims that naturally engender counterclaims, but nobody doubts the innovative reality of his overall presence. (Charles Hamm’s recent book, with its stuffed mouthful of a title, Irving Berlin: Songs from the Melting Pot: The Formative Years, 1907-1914, offers little biography but does clarify the ways in which Berlin early broke new musical ground.)

Still, most of what Berlin wrote in the Teens has either faded from sight or taken on the brittle, stylized charm of the period piece. It wasn’t until the Twenties and Thirties that Berlin regularly began writing songs which, though resonant of their era, shook off their dated charm to speak with an air of timelessness. Many but not all of these were ballads: “Always,” “Blue Skies,” “Lazy,” “Remember,” “The Song Is Ended,” “Supper Time,” the scores from the films Top Hat and Follow the Fleet, and my favorite of his songs, that simple, heartbroken-in-advance waltz “What’ll I Do?” (The night Ellin met Irving, she praised his song “What Shall I Do?” Between those two future lovers, a formidable culture/class gap yawned.)

Berlin wrote so many songs, over so many years, that the sifting of his work is necessarily a slow and halting process, but it does look as though the Berlin that posterity has most firmly embraced is the one working in the decade-and-a-half from 1924 to about 1939. It’s certainly the period from which recent recording artists have chosen to draw. Twenty-seven out of the thirty-two songs in Ella Fitzgerald’s The Irving Berlin Songbook derive from this period, as do eleven of fifteen on Kiri Te Kanawa’s Berlin album, and twenty-four out of thirty-three on Andrea Marcovicci’s.

Berlin wrote few songs during the Second World War—largely because he nobly devoted most of four years to taking This Is the Army (a sequel to Yip! Yip! Yaphank, his musical revue from the First World War) all over the world: Broadway, Hollywood, London, Rome, Cairo, New Guinea, and numerous flyspeck islands in the Pacific. Although he was in his mid-fifties at the time, and could well have begged off the job, Berlin dutifully—sometimes in danger, frequently in sweltering discomfort—served “our boys” by carrying on with the show.

All the more impressive, then, was Berlin’s comeback with Annie Get Your Gun, in 1946. He signed on to the project after its original songwriter, Jerome Kern, died just as things were getting underway. Berlin hesitated about stepping in—chary, in his fiercely independent way, about adopting any other man’s project, and fearful that “hillbilly music” was unsuited to his talents. It proved to be not only his biggest stage success but, by one measure, the biggest Broadway success ever, yielding more hit songs than any other musical before or since. (These include: “There’s No Business Like Show Business,” “Doin’ What Comes Natur’lly,” “You Can’t Get a Man with a Gun,” “They Say It’s Wonderful,” “Anything You Can Do.” The original production, with Ethel Merman booming in the title role, ran through 1,147 performances.) Annie Get Your Gun was much the most plot-driven musical Berlin had attempted—far closer in spirit to Rogers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! or Carousel than to the scattershot revues he had grown up on.

At first glance, Berlin must have seen little in common between himself and his heroine, Annie Oakley, the sharpshooting star of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. Berlin was a rich, urban, dapper, East Coast late-middle-aged man; Oakley was a poor, backwoods, ragged young girl from the prairies. But Annie, like Irving, was born with a God-given, up-from-nowhere knack—a talent that would propel her triumphantly across the world. And that Berlin discovered an affinity with his young, plucky heroine is apparent not only in the music he composed for her but in the speed with which it arrived.

More than half a century later, a revived, revised Annie Get Your Gun has come to Broadway, with Bernadette Peters in the title role and Tom Wopat as her romantic foil and target, Frank Butler. Graciela Daniele is director and choreographer. The advance publicity focused largely on the updating of Herbert and Dorothy Fields’ original book, which had grown creaky over time, particularly in its depiction of Indians. This unenviable task fell to Peter Stone, who was open on one flank to charges of tampering with a sacred text in the name of political correctness and on the other to accusations of continuing insensitivity.

In fact it’s hard to imagine Berlin’s objecting to this attempt to defer to our increased sensitivity to racial stereotyping. He was the one who said, “I write a song to please the public—and if the public doesn’t like it in New Haven, I change it!” Yet no amount of mere tinkering can conceal the sad fact that, in this particular Wild West show, there is too much sand between waterholes; Annie Get Your Gun has a weak book and no simple updating will solve the problem. Peters and Wopat are appealing presences, and you can’t help cringing a little when they’re asked to present extended stretches of dialogue. The exposition is clumsy, most of the jokes are dopey, and the audience waits impatiently for the next song.

Among these, “They Say It’s Wonderful” has always struck me as one of Berlin’s most winsome ballads. Crystallizing a moment when rough-hewn Annie has begun to succumb to tenderer sentiments, it perches beautifully, in melody and lyrics, between exultation (“Falling in love is wonderful/It’s wonderful”) and qualification (“so they say,” “so they tell me”). Listening to Bernadette Peters deliver it, you can’t help feeling that in germinal form we have here a first-rate musical, like West Side Story or My Fair Lady—one which, like My Fair Lady, would tell a universal tale of emergence, a blossoming forth from expectant inexperience into requited passion.

Peters’s voice has a sweetness that Merman’s never aspired to, and the two performers highlight the essential differences between songs on the stage and songs in the recording studio. Stage performances, because they’re usually experienced only once, often succeed best when everything is outsize and exaggerated. Recordings are another matter. Because the listener is meant to return to them again and again, a little of anything goes a long way. By most accounts, Merman was an unbeatable Annie on Broadway, and yet on the cast recording her brassy, outflung, wake-up-the-drowsing-drunk-in-the-last-row-of-the-theater style soon cloys. My guess is that in the long run, when the present show closes up and is eventually folded into the little box of a CD container, Peters will turn out to be the more appealing star.

In any event, there’s one moment in the present production that could hardly be bettered: a fresh, funny, lovely rendition by Peters and Wopat of the contrapuntal duet “An Old-Fashioned Wedding.” Berlin composed the song twenty years after the original show, to supplement a Merman revival of 1966. Like the Gershwins’ “Our Love Is Here to Stay,” which Ira informs us was the last song George wrote, “An Old-Fashioned Wedding” vibrates with the bittersweet poignancy of a joyous farewell. By 1966, Berlin had retired from songwriting. And yet the old man (seventy-eight when the revival opened) somehow did it one more time: went ransacking in the trunk of his brain and came up with a winner.

If the world made more sense, Berlin would have written not one but at least a handful of enduring musicals. Unlike a number of his contemporaries who largely abandoned the East Coast for the West Coast and theater for film (Ira Gershwin, Jerome Kern, Harold Arlen), Berlin stayed a dedicated New Yorker, with a mansion overlooking the East River and an office near Times Square. Yet Berlin never seemed to find exactly the right book for a musical, and his finest dramatic work remains the material he composed in the mid-Thirties while sojourning out in California: the two scores he created for Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, Top Hat and Follow the Fleet.

Top Hat is the film I’ve seen more times than any other—I’ve lost count how many—and never without a replenishing sense of how beautifully Berlin’s music highlights Astaire’s dancing and voice, his airy affect and cherubic mugging. The score is varied and gorgeous: “Cheek to Cheek,” “No Strings,” “Top Hat, White Tie, and Tails,” “The Piccolino.” There are days when I’d swear that the bandstand sequence, in which, all to the strains of “Isn’t This a Lovely Day,” a smitten Fred reveals to Ginger that he’s actually a dancer, and Ginger (to Fred’s marveling elation) reveals that she can manage a few steps herself, may be the most magical minutes ever put to celluloid. (Other days, I’d swear it’s the final sequence of Follow the Fleet, where “Let’s Face the Music and Dance” progresses from mimed solitary contemplations of suicide to an ecstatic, unified seizing of life and romance.) There’s something faintly laughable to Astaire’s charm (the slicked hair, the devoted puppy eyes, the newel post of a chin), and today his appeals can look quaint—until he explodes in a hummingbird’s show of weightless virtuosity…. Likewise, there’s something lightly laughable and quaint to Berlin’s tinkling score, until it too explodes, opening out in a breathless passionate embrace of all those virtues that made the Astaire films so peerless: suavity and sweetness, legerity and longing.

At the age of fifty-seven, Berlin received the Medal of Merit—the nation’s second-highest honor—pinned to his lapel by General George Marshall himself. An acknowledgment of Berlin’s contributions to the war effort, as well as his acts of civic charity (such as donating all proceeds from “God Bless America” to the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts), the award also corroborated something larger: that Berlin, alone among living songwriters, had made himself a national figurehead. One could say of him, as Jerome Kern did in a much-repeated remark, “Berlin has no place in American music. HE IS AMERICAN MUSIC.”

As such, he seems to inhabit a zone safely beyond criticism. So it comes as something of a shock to encounter, in Bergreen’s biography, numerous calmly set out incidents showing that Berlin could be foul-mouthed and paranoid when not being gracious and trusting; could be extraordinarily chilly and greedy when not being munificent; could be spiteful and dictatorial when not being compassionate. One comes away suspecting that, in their reminiscences and memoirs, Berlin’s family and friends and business acquaintances have loyally softened and sweetened his portrait.

What cannot be concealed is that Berlin in the last few decades of his life retreated into the plush chambers of a privileged recluse. After the critics pounded his last big effort, Mr. President, in 1962, he slowly abandoned the everyday world that heretofore had served him as inspiration and touchstone. His home on the Upper East Side became a fortress, into which fewer and fewer friends gained admission. He embroiled himself in bitter, ill-advised lawsuits. He was getting on in years—seventy-four when Mr. President opened—but, as his business dealings made clear, he kept his faculties throughout his eighties and nineties. He knew his preferences, and he saw hardly anyone but wife and servants. For a time, according to Mary Ellin Barrett, “Even family visits were discouraged and eventually stopped entirely.” Friendships, family matters, business decisions—to the extent that these had to be attended to, they could be handled by telephone.

To understand Berlin’s last two decades, we need a solider understanding of his first two decades than his biographers have provided. Or perhaps one should say that Berlin succeeded too well with his first biographer, his friend Alexander Woollcott, whose hastily assembled The Story of Irving Berlin appeared back in 1925. Berlin was Woollcott’s primary and often unquestioned source, and the resultant portrayal of Irving’s childhood, although poignant, abounds in implausibilities. Even so, it has been embraced, in one form or another, by every subsequent biographer.

Perhaps it’s true that at the age of fourteen Berlin left home—“went on the bum”—and stayed away for some two years, sleeping in lice-infested rooming houses and on park benches, and singing in the streets and saloons, all within a few blocks of the family home. Or perhaps it’s an exaggerated tale. Either way, the boy’s ostensible reason for leaving—a sense of guilt at being a drain on family resources—looks somewhat self-protective. Either way, it deflects attention from the troubled domestic situation that such a flight might imply. This is all uncertain terrain, but I wonder about Woollcott’s account, which gives this report of Mrs. Baline’s response to her son’s running away: “Probably her heart was more than a little wrung. But she was too loving and too gallant to let her son suspect it.” (In sorting out Berlin’s childhood, it doesn’t help matters that two incisive critics, Robert Kimball and Gary Giddins, as well as Philip Furia in his earlier The Poets of Tin Pan Alley, all erroneously report that Berlin was eight when his father died rather than thirteen, thereby eliminating any proximate link between Moses’s death and Irving’s desertion.)

Whatever bugbears may lie hidden in the Berlin household (further evidence for which might be found in the eventual suicide of Irving’s oldest sister, Sarah), Berlin exulted in making things right: he relished the tale of the day he drove with his mother north into the Bronx, to present her with the house she would live in henceforth. The hard times were seemingly behind them…. But that their hard times could never be put fully behind them was suggested by Berlin’s daily battles with a hair-trigger temper, his nightly battles with insomnia, and his intermittent struggles with bouts of depression that would lead to breakdowns and rest cures. The curmudgeon of his last few decades did not emerge from nowhere. No, the wonder is that, given the hardship of his childhood, Irving Berlin negotiated life as successfully as he did: working at his music not just brilliantly but dependably, serving his country with pride and honor, drawing sustenance from a loving marriage, showing himself to be a devoted and solicitous father.

In truth, one scarcely needs a biography of Berlin to sense a private core of pain. Sorrow and melancholy are adrift in his music, not merely in his “sob ballads”—his tales of heartbreak and abandonment—but even in his ostensibly jubilant songs. What song has a cheerier lyric than “Blue Skies,” which Berlin told Mary Ellin Barrett was written in celebration of her birth?

Blue skies, smiling at me,

Nothing but blue skies do I see.

Blue birds, singing a song,

Nothing but blue birds all day long.

Yet singers of various stripes and eras—everyone from Frank Sinatra in the Forties and Dinah Washington in the Fifties to Kiri Te Kanawa and Cassandra Wilson in the Eighties—have detected a different, darker shade of “blue” in those blue skies. It’s present only fleetingly in the lyrics (“blue days, all of them gone”) but it subtly haunts the melody. Things may be wonderful now, the song intimates, but they haven’t always been. The sun may be shining now, but there’s been a hell of a lot of rain.

It would be easy to call Berlin a misanthrope, but misanthropy (as Berlin’s own life so tellingly illustrates) is often a complicated business in the case of an artist. A mathematician, a locksmith, a stock-picker, a farmer—people in professions like these can go steadily about their work while viewing the rest of humanity with disdain or indifference. Not so the individual whose chosen ambition involves reading the mood of the general public in order to please them.

Seen from a distance, this ambition is revealed as almost a model of purest altruism: the artist’s mysterious urge to grace the lives of perfect strangers with joy and solace and an invigorating beauty. However much their motivations may be cankered by egotism or competitiveness or selfishness, artists often wind up being generous despite themselves—theirs a generosity circulating in the very blood of their creative impulses. This is particularly true of the popular songwriter, whose natural goal is to introduce color—vivid melodies, brilliant lyrics—into drab lives. Berlin, Gershwin, Kern, Arlen, Porter, Rogers, Carmichael: these people brighten the world.

By the final decades of his life, Berlin knew exactly what he wanted: to avoid people. But he couldn’t stop wanting something else as well: to make them happy.

This Issue

April 22, 1999