To the Editors:

We think your readers may be interested in the accompanying letter by Xu Jin, the daughter of Xu Wenli, who was, in 1998, sentenced to thirteen years in prison for trying to form an opposition political party. Both Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have urged his immediate and unconditional release. In her letter Xu Jin gives an account of her mother’s recent visit to the prison and of her husband’s treatment by the prison officials.

Mr. Xu, of course, is only one of thousands of political prisoners who are kept in similar conditions in China. Accompanying Ms. Xu Jin’s letter is a list, compiled by Human Rights in China, of some of the better known political prisoners who are serving long sentences, and whose cases are of urgent concern.

Both Ms. Xu Jin’s letter and this list should, we suggest, be brought to the attention of the more than four hundred “chief executives, scholars, economists, and world leaders” who will meet in Shanghai on September 17 at a conference organized by Fortune magazine. The keynote speech for the meeting will be given by President Jiang Zemin. In addition to many American businessmen, “a delegation of the leaders from China’s largest companies and State-Owned Enterprises will also participate.” But as circulated by Fortune, the planned agenda of the conference—which we have been told is open to revision—provides for no discussion whatever of the problems of human rights that are now occurring in China.

There is no mention, for example, of the use of prison labor to make Chinese products that are exported to the United States. Nor is there any provision in the agenda for discussion of such questions as the suppression of members of the Falun Gong, a non-violent spiritual movement, or for the arrest of Chinese citizens who have tried to establish the Democracy Party as an independent political organization under the Chinese constitution. Nor is there any provision for discussion of the restrictions the Chinese government has been placing on the use of the Internet.

These are only a few of the subjects bearing on basic human rights that would seem appropriate for executives of large American and other international corporations to discuss with the Chinese government and business leaders they will meet in Shanghai. We hope that the invited executives and Fortune magazine will want to revise their agenda to allow discus-sion of them. The participants should be aware that during the last two years the Chinese government has signed both the UN International Covenants on Political and Civil Rights and the UNInternational Covenants on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. The cases described below show clear violations of these recognized standards by the Chinese government.

Whether or not Fortune magazine is willing to include such matters, we hope that the assembled executives themselves will feel that, as a matter of conscience, they should raise such questions in their meetings with Chinese authorities. They might, we suggest, consider giving those authorities copies both of the letter from Ms. Xu Jin and of the list of political prisoners that follow, and asking what can be done to allow such nonviolent citizens elementary liberties.

Robert L. Bernstein

Fang Lizhi

Board members

Human Rights in China

350 Fifth Avenue, Suite 3309

New York, N.Y. 10118

Tel.: (212) 239-4495

E-mail: hrichina@igc.apc.org

From Xu Jin, daughter of Xu Wenli, on his health in prison:

On July 9, my father, Xu Wenli, observed his fifty-sixth birthday in Yanqing prison in Beijing. There was no cake, no candles, no songs, and none of his family were there to help him celebrate. He’ll spend many more birthdays alone. On December 21, 1998, he was sentenced to thirteen years in prison for helping to form an independent opposition political party. My mom, He Xintong, and I don’t know how he spent the day, probably like every other day, reading, writing a little, idle most of the time. More critically, we don’t know the state of his health and we don’t know what we can do to persuade prison authorities to allow him to be thoroughly checked in a medical facility outside the prison and to have the complete results made available to us, his family.

During my mother’s last prison visit, on June 21, she learned that my father was ill back in March and April. He didn’t want to tell her until at least the symptoms were under control. First my dad’s feet became so swollen that he couldn’t put on his shoes. Then his arms and legs and finally his whole body became swollen. After he reported the problem to prison authorities, the prison doctor ran some tests and prescribed a diuretic and the swelling subsided. We have no idea, nor does my father, what caused the problem. But he decided, on his own, to replace the Western medicine he had been given with traditional Chinese herbs.

My father is allowed to write one letter and one “visit postcard” a month to my mother. The postcard comes just before her monthly visit to him and it contains a list of items she should bring. In June, he asked for the herbs, but before the prison authorities mailed the card, they crossed out that request. Instead, my mother has to pay the prison authorities to supply the herbs.

The day after my mother’s June visit, she made some inquiries about what could have caused all that swelling and what kind of tests he should have to determine an accurate diagnosis. She found out his symptoms could have come from heart, kidney, or liver problems. After all, my dad is fifty-six and he’s spent over twelve years in prison. Then she went to the prison’s control center and asked to see the supervisor. Her request was denied. With no other choice available, she wrote to the supervisor and to the warden at Yanqing prison. First of all, she asked for him to be evaluated by a specialist outside prison. She suggested some particular medical tests, and requested the results be made available to her so she could have them independently assessed.

My mom also asked, as she has since my father was sentenced, that his teeth be repaired so he can eat and speak properly. During the twelve years he spent in prison, from 1981 to 1993, he lost most of his teeth. During 1997, he tried to have them repaired, but the work was unsuccessful. Instead, a prison dentist has begun to make him false teeth at the family’s expense. So far, he has four, but they are so ill-fitting he has to take them out to talk and eating is still a problem.

Today is August 15, and still nobody has answered my mom’s letters. She called the prison but couldn’t get any information. According to China’s 1992 White Paper on Criminal Reform, Xu Wenli has “the right to maintain good health.” Outside medical experts can be consulted for diagnostic purposes and he may be sent to an outside hospital for treatment. As family members, my mother and I deserve an explanation of my father’s condition. We ask again that Chinese authorities respond in full to our minimal requests as a matter of common human decency.

US Contact:

Xu Jin

Tel.: (617) 264-7213

E-mail: jx@bu.edu

China Contact:

He Xintong

Tel.: 011-86-10-63527814

CASES OF URGENT CONCERNIN CHINA, COMPILED BYHUMAN RIGHTS IN CHINA

Prison Sentences

China Democracy Party (CDP) Members

Xu Wenli, fifty-six, was arrested on November 30, 1998, for “endangering state security” in connection with his efforts to establish the China Democracy Party. On the night he was taken away by the police, officers made an exhaustive search of his home, confiscating a computer, address books, and documents related to the opposition party. He was sentenced to thirteen years’ imprisonment following a one-day trial on December 21, 1998. A veteran democracy activist, Xu served twelve years in prison following his participation in the Democracy Wall Movement in 1979.

Qin Yongmin, activist and author, was arrested on November 30, 1998, for “endangering state security” and sentenced to twelve years’ imprisonment after his December 17, 1998, trial. Chinese officials claimed that his role in preparing for the establishment of the China Democracy Party “breached the relevant provisions of China’s criminal laws.” Qin served seven years in prison for his participation in the Democracy Wall Movement and three years in Reeducation Through Labor for his participation in drafting the Peace Charter.

Wang Youcai, thirty-two, a former student democracy leader, was detained on November 2, 1998, in connection with his leading role in seeking to officially establish the China Democracy Party. He was formally charged on November 30, 1998, for “conspiring to subvert the government,” organizing a meeting of party supporters, using e-mail to send party materials abroad, and accepting funds from overseas to buy a computer. He was sentenced to eleven years’ imprisonment after being tried by the Hangzhou Intermediate Court on December 17, 1998.

Liu Xianbin, a leading CDP member in Sichuan, was sentenced on August 6, 1999, to thirteen years’ imprisonment for subverting state power. Liu was unable to find defense counsel as a series of lawyers withdrew from the case following pressure from the authorities. He spoke in his own defense at the Suining Intermediate People’s Court. Liu, who was detained without warrant on July 7, 1999, previously served two years in prison for his participation in the 1989 democracy movement.

She Wanbao, a CDP member, received a twelve-year sentence for subversion on August 5, 1999, following a three-hour trial in Guangyuan, Sichuan. She was taken from his home without warrant on July 7, 1999. A forty-one-year-old former bank official, She spent four years in prison for taking part in the 1989 demonstrations.

Zha Jianguo and Gao Hongming, chairmen of the CDP’s Beijing-Tianjin branch, were sentenced for subversion on August 2, 1999, receiving prison terms of nine and eight years, respectively. Zha and Gao, who were detained on June 29, 1999, both had collaborated with Xu Wenli. Zha is a former manager of a computer design company. In April, Gao, a former office administrator, had announced plans to set up an independent labor union with Xu Yonghai, a Christian activist, and had also pressed China’s leaders to take responsibility for the “June Fourth Incident.”

Beijing Fifteen

Liu Jingsheng is one of the “Beijing Fifteen,” the largest group of labor and democracy activists to be tried since 1989. They were given some of the heaviest sentences handed down to political prisoners in recent years: Hu Shigen, twenty years’ imprisonment; Kang Yuchun, seventeen years; Wang Guoqi, eleven years; Zhang Chunzu, Chen Wei, Lu Zhigang, and Wang Tiancheng each received five-year terms; Rui Chaohuai, three years; and Li Quanli was given two years’ supervision, while five others were found guilty and freed. Arrested in 1992, the group spent two years in incommunicado detention until their trial in July 1994, where they were found guilty of various “counterrevolutionary offenses,” including plans to drop leaflets on Tiananmen Square using a remote-control toy airplane on the third anniversary of June Fourth. When their appeal was rejected in July 1995, they chanted “Long live free trade unions in China” and “Long live democracy” in the court. Liu Jingsheng himself was charged as a “chief conspirator” for “organizing and leading a counterrevolutionary group” and carrying out “counterrevolutionary propaganda and incitement,” and was sentenced to fifteen years.

June Fourth Activists

Yu Dongyue is serving a twenty-year prison term for defacing the Mao portrait in Tiananmen Square. Yu, a former editor at the Jiyang Daily who refused to acknowledge his guilt or cooperate with authorities, has been savagely beaten and kept in a tiny isolation cell at the Yuanjian Labor Reform Camp in Hunan, which has brought on severe mental illness.

Li Hai, forty-four, a former Beijing student and leader of the 1989 democracy movement, was arrested in 1995 for making public a list of individuals who are serving lengthy prison sentences for their participation in the 1989 demonstrations. He was subsequently sentenced to a nine-year prison term for “prying into and gathering” “high-level state secrets.”

Mongolian Activist

Hada, forty-one, owner of the Mongolian Studies Bookstore in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, was sentenced in 1966 to fifteen years’ imprisonment for his role as founder and chair of the Southern Mongolian Democratic Alliance (SMDA), a group which called for increased autonomy in Inner Mongolia and respect for the rights and culture of China’s minority peoples. Hada was taken from his home in December 1995 during a crackdown on Inner Mongolian democracy and autonomy activists, and was originally held in the Inner Mongolia Public Security detention center under shelter and investigation provisions before being formally arrested in March 1996, when he was charged with “conspiring to subvert the government,” “spying,” and “splitting the country.” Hada is currently imprisoned in Inner Mongolia’s No. 1 Prison.

Human Rights Monitor

Chen Meng, thirty-seven, is serving a twelve-year prison sentence in Dongguan, Guangdong Province. He was found guilty of faxing a top-secret document to “organizations outside China’s borders,” thus damaging the “reputation” of the government. This was a list of forty-nine Chinese nationals or former nationals either barred from entering China or subject to arrest or other measures on their arrival at the border. Chen was tried by the Shenzhen Intermediate People’s Court in a closed proceeding on an unknown date in 1996 and convicted of illegally providing state secrets. Chen has reportedly been held in solitary confinement since he was detained on March 14, 1995, and is said to be suffering from serious liver disease.

Labor Activists

Zhang Shanguang, a Hunan labor activist, was sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment on December 27, 1998, after a two-hour trial held behind closed doors. He was found guilty of “providing intelligence to institutions outside the borders.” According to the verdict, Zhang had given information to foreign organizations, including a journalist from Radio Free Asia who had interviewed him about a demonstration organized by farmers and workers in Hunan Province. However, Zhang’s attempt at establishing the Association to Protect the Rights and Interests of Laid-Off Workers in Xupu County is considered a main reason for the harsh sentence. He was initially detained on July 21, 1998, and formally arrested on August 28, 1998.

Yue Tianxiang, a labor rights activist, was sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment in July 1999 for “subversion.” Yue, who was detained on January 11 and formally charged on January 26, 1999, formed the China Labor Rights Observer in Gansu Province to protect the rights of laid-off workers. Guo Xinming and Wang Fengshan, who worked with Yue to establish the China Labor Rights Observer and were apprehended with him, were each sentenced to two years in prison, also for subversion.

Li Bifeng, thirty-four, a labor activist and former tax department employee, was found guilty of “fraud” by the Mianyang People’s Court of Sichuan in late August 1998. After a one-day trial that lacked all due process, Li was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment. Li was detained in March 1998 and charged one month later. A representative of the unofficial Chinese Conscience and Care Action organization, he released information about laid-off workers’ protests and living conditions. In December 1997, Li wrote to the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party to urge them to “free all political prisoners…and end one-party rule.” He had already spent five years in prison for his involvement in the 1989 democracy movement.

Tibetan Religious Leader

Chadrel Rinpoche, fifty-eight, the former abbot of Tashilhumpo monastery and head of the official search team for the reincarnation of the tenth Panchen Lama, was sentenced in April 1997 to six years for allegedly “conspiring to split the country,” “colluding with separatist forces abroad,” “seriously jeopardizing the national unification and unity of ethnic groups,” and “leaking state secrets.” Chadrel Rinpoche is reportedly detained in a secret compound in Changdong No. 3 Prison, Dazu County, Sichuan Province, where he is denied all outside contacts and is restricted to his cell.

Political Reformer

Fang Jue, forty-four, a former government official turned businessman, was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment on June 10, 1999, for “embezzlement” and “illegal business practices,” charges that Fang denounced as a government “frame-up.” During his four-hour trial on April 6, 1999, Fang was not allowed to present his statement. Initially detained in July 1998 and held incommunicado, Fang Jue was the primary drafter of “China Needs a New Transformation,” a platform for political reform that was issued in November 1997.

Freedom of Expression Advocates

Liu Xianli of Anhui was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment for subversion on May 10, 1999, after attempting to interview China’s prominent dissidents for a book on their activities. Liu was detained in March 1998 and tried in November 1998.

Wei Hongyang was sentenced to five years in prison and fined 30,000 yuan by a court in southern Guangdong Province in early June 1999 for publishing 38,000 “illegal political publications.” The printer, Deng Zhifei, was sentenced to four years and fined 40,000 yuan. The sentences, which came amid the pre-June Fourth security clampdown, was to serve as a warning to others not to undertake such work, according to an official quoted by the local official paper.

Grass-Roots Democracy Activist

Zhao Changqing, twenty-eight, was sentenced in early September 1998 by the Hanzhong Intermediate Court (Shaanxi) to a three-year prison term. At the time of sentencing, the date and length of his sentence, his place of detention, and the charges against him were all kept secret. Zhao was detained after he tried to run in local legislative elections. Although he had gathered enough supporting signatures, he was told that only CCP cadres at or above the deputy director rank were eligible.

Human Rights Activist

Fan Yiping, forty-three, was fined 10,000 yuan and sentenced to three years’ imprisonment by the Guangzhou Intermediate People’s Court on July 21, 1998. During the trial, which began on July 13, 1998, Fan pleaded not guilty to the charge of illegally organizing Wang Xizhe’s flight to Hong Kong in October 1996. The trial was riddled with discrepancies including forced witness testimony, absent witnesses, and insufficient notification. A company manager, Fan was detained in March and formally arrested in May 1998. During the Democracy Wall movement Fan headed the unofficial publication Voice of the People.

Cyber Prisoner

Lin Hai, a thirty-year-old computer company owner in Shanghai, was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment for subversion on January 20, 1999. He was detained on March 25, 1998, after he allegedly provided Chinese e-mail addresses to the US-based on-line magazine Dacankao, also known as VIP Reference. VIP Reference, which is described by prosecutors as a “hostile foreign publication,” compiles and distributes articles on dissident activities, human rights, and other issues to more than 200,000 e-mail addresses in China. Lin Hai’s trial was held on December 4, 1998, behind closed doors because of the “state secrets” allegedly involved in his case.

Reeducation Through Labor

Shen Liangqing, thirty-five, a former public prosecutor in Anhui, was sentenced in March 1998 to two years of Reeducation Through Labor for “disturbing social order.” Shen had issued a number of open letters to the government and published critical essays abroad, which led to repeated detentions. In January 1997 he had been retroactively sentenced to seventeen months’ imprisonment for his role in drafting, printing, and distributing “subversive” pamphlets in Hefei in 1991.

Wang Tingjin, forty-three, a math teacher in Anhui, was sentenced in April 1998 to two years of Reeducation Through Labor for “disturbing social order.” In February he spent one month in detention after meeting with New York-based dissident Wang Bingzhang on a clandestine trip to China.

Yang Qinheng, forty-four, was arrested in late February 1998 and sentenced to three years of Reeducation Through Labor in April 1998. Active in petition campaigns, Yang called for the reassessment of the official verdict on the Tiananmen Square Massacre and the release of political prisoners. He read on Radio Free Asia an open letter that condemned China’s policy on unemployment and argued for the right to form free trade unions.

Awaiting Trial

Jian Qisheng, June Fourth victims’ advocate, was detained on May 18, 1999, following his leading role in planning June Fourth anniversary activities. On April 15, 1999, Jiang and a group of fifteen activists issued an open letter calling for all the people of China to commemorate those killed in the 1989 massacre. On May 17, Jiang issued a one-man appeal on behalf of Cao Jiahe, the Dongfang magazine editor who was arbitrarily detained and tortured for collecting signatures to mark the June Fourth anniversary. On July 16, two Beijing police officers verbally informed his wife, Zhang Hong, that Jiang Qisheng had been formally arrested several days earlier on the charge of “propagating and instigating subversion.” Jiang’s trial is imminent, though no date has been announced.

Liao Shihua, a prominent labor activist, was detained on June 12, 1999, accused of “inciting the masses to attack an organ of government.” Liao had been missing since June 7, 1999, when he joined over 100 laid-off workers demonstrating in front of Hunan provincial government headquarters, demanding a resolution to the area’s unemployment problems.

Tong Shidong, an assistant professor in Hunan University’s Physics Department, was officially arrested on June 15, 1999, on the charge of “conspiring to subvert the government.” Taken from his home on June 8, 1999, by the political section of the Public Security Bureau of Changsha City, Hunan Province, Tong is now being held at the Changsha City Detention Center. On November 19, 1998, Tong and Peng Yuchang, a retired lecturer, declared the formation of the Hunan University’s preparatory committee of the China Democracy Party, the first among universities. Tong was responsible for drafting the chapter’s documents to apply for official registration.

Hua Di, sixty-four, a missile expert affiliated with Stanford University, has been charged with “revealing state secrets,” but his trial has been repeatedly postponed for lack of evidence. Hua, who sought political exile in the United States following the 1989 crackdown and settled in California, was arrested in January 1999 while visiting his family in Beijing. Hua is suffering from a rare form of male breast cancer. His family has appealed to the Beijing People’s Intermediate Court for Hua’s release on medical parole, but has received no response.

Extended Sentences

Han Lifu, a member of the CDP, has been sentenced to two additional years of Reeducation Through Labor. Han was originally sentenced to nine months of “shelter for reeducation” in October 1998 in connection with his role in establishing the CDP Shanghai Forming Committee. The extension of Han’s detention, imposed for his defiance of his original sentence, was discovered only when family members arrived at his detention center to pick him up on his July 22, 1999, release date. Cai Guihua, a fellow CDP member who organized weekly study groups on human rights in Shanghai with Han, has also been given an extended Reeducation Through Labor term.

Ngawang Sangdrol, twenty-two, a nun from Garu nunnery, has had her sentence increased by four years for leading the May 1998 prisoner protests in Drapchi Prison. This is the third time that her prison term has been extended since her original sentence to three years’ imprisonment in 1992 for taking part in a peaceful pro-independence demonstration in Lhasa. In October 1993, she was sentenced to an additional six years for composing and recording pro-independence songs in prison, and in July 1996 her sentence was increased again by eight years for minor acts of disobedience. Ngawang Sangdrol is now serving a twenty-one-year sentence, the longest imposed on any female political prisoner in Tibet.

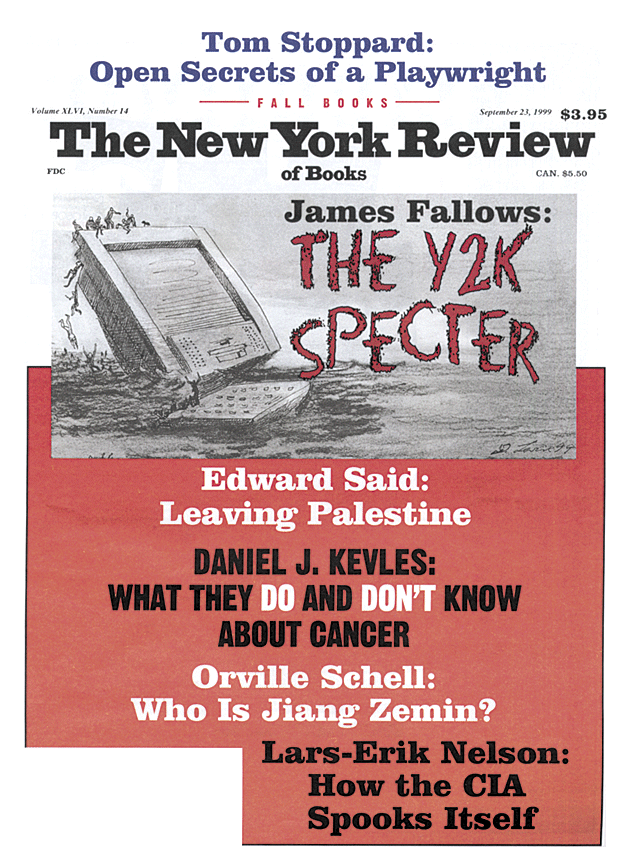

This Issue

September 23, 1999