To the Editors:

In my article “The Pope, the Nazis, and the Jews” [NYR, March 23], I wrote that Catholics “must believe unconditionally not only that [Holy] Mary was born without the original sin burdening the rest of the humanity; not only that she remained a virgin despite conceiving and giving birth to Christ as well as to Christ’s four brothers and to his sisters (Mark 6:3); but that, after she died, her body and soul were immediately reunited.” I said all this in an attempt to show that in Catholicism the periodic surrender of rational thinking is even more essential than in most other varieties of Christianity, or in some other religions. Such mystical beliefs generally emanate from, and are controlled by, the highest authority in the Catholic Church: the Pope.

However, two readers took me to task by stating that according to eminent scholars of scripture, the relevant passage in Saint Mark’s version of the Gospel should not be interpreted literally. Some have seen the brothers James, Joses,Juda, and Simon, as well as the unnamed sisters, as having been born from another, supposed marriage by Saint Joseph; others have found in the New Testament another Mary as the mother of at least some of the brothers; and again other scholars argue that Saint Mark’s original Greek terms for brother and sister may have had a wider meaning, such as brethren.

I find such scholastic argumentation fascinating, especially in this secular world, and I won’t even try to disagree with scholars who have devoted their life to the study of the New Testament. If all this is true, however, I wonder why some Church scholars have seen Saint Joseph as no less of a perpetual virgin than Mary herself, and why Saint Mark lists the four men clearly as the brothers of “the carpenter, the son of Mary,” who at that moment happens to be teaching in the synagogue of his home town. Moreover, if there is something wrong with the translation from the Greek, why has the text not been corrected, whether in English, German, French, or Hungarian? After all, what can Catholics who are not scriptural scholars believe in if not what they read in the Gospel, a text that is said to be divinely inspired?

Several keen-eyed readers have reminded me, correctly, that Eugenio Pacelli, the future Pius XII, was made an archbishop in 1917, not yet a cardinal. Also, that Imistakenly placed him in Berlin in 1936. Furthermore, a professor of medieval history declared that Iwas wrong to refer to the schism of 1054 between Eastern and Western Christianity as “the Great Schism”; the term, according to him, refers exclusively to a schism within Western Christianity that lasted from 1378 to 1415. Here I am a little less conciliatory, however, because, according to my edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, the name Great Schism refers to what happened in 1054. Other historians, especially those not writing in English, distinguish between the Eastern (1054) and Western (1378-1415) schisms, while not awarding the honorific term “Great” to either of these events. Other sources refer to what happened in 1054 as the “Final Schism.”

In fact, the schism of the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, which saw the emergence of a Roman and a French-supported “Avignonese”papacy, remained without profound consequences for Christianity and Western civilization. During the schism there were two, and for a short period, even three competing popes, but this Great Schism ended at the Council of Constance in 1415-1417. On the other hand, the split in 1054 between East and West has fatally determined constitutional, political, literary, and artistic developments in the two halves of Europe. The most recent bloody conflict between Western and Eastern Christianity has been fought out in Bosnia.

Unlike readers who reproach me for being too harsh on John Cornwell, the author of Hitler’s Pope, the historian Susan Zuccotti, in a letter to The New York Review, criticizes Cornwell for accepting the claims of papal defenders regarding Pius XII’s role in the saving of Italian Jews. According to Zuccotti, “the many Italian bishops, priests, and monks” who sheltered Jews during the war “did not claim, then or later, that Pius XII asked or even encouraged them to do it. Some actually even denied a papal role.” Zuccotti knows the Vatican documents as well as anyone; still, I feel, this time with Cornwell, that all the saving actions by priests and nuns in Italy would have been less likely without some understanding on their part that they had papal approval, however tacit that approval may have been. In the same way, the apostolic nuncios in Slovakia, Romania, and Hungary might have been less active on behalf of the Jews had they not felt they had the Vatican’s support.

All this in no way excuses the Pope’s inaction, in October 1943, when the Germans deported a thousand Jews in Rome literally from under his windows. In my article I argued that this would have been the opportune moment for the Pope to appear at the Trastevere railroad station, with at least part of his retinue, and demand the release of the Jewish deportees. Even if he were not successful, the news of such a magnificent gesture would have spread in Europe, possibly influencing Catholics everywhere. The writer Gregory Conti has reminded me in a recent letter that I wasn’t the first one to think of this. Rosetta Loy, in her book, La parola ebreo, published in 1997, suggested that Pius XII could have stood in front of the train to block its departure instead of remaining in his rooms. The book, translated by Conti, will soon appear in English as First Words: A Memoir.*

Inactive in October 1943, the Vatican shamefully facilitated the escape of many of the chief Nazi mass murderers after the war. As I wrote in my article, this too would have been most unlikely without at least the Pope’s unspoken approval. However, the Church’s attempt to shelter at least some of the Jews in Italy, Western Europe, and some parts of Eastern Europe (but not in Germany or Poland) took place during the war. The sheltering of the Nazi mass murderers occurred after the war when the Pope, as I wrote, acted as the very first cold warrior. The man who preferred diplomacy, or even inaction, to confrontation while Hitler was alive, called for immediate reconciliation with Germany after 1945 and led the way to confrontation with Stalin.

István Deák

Columbia University

New York City

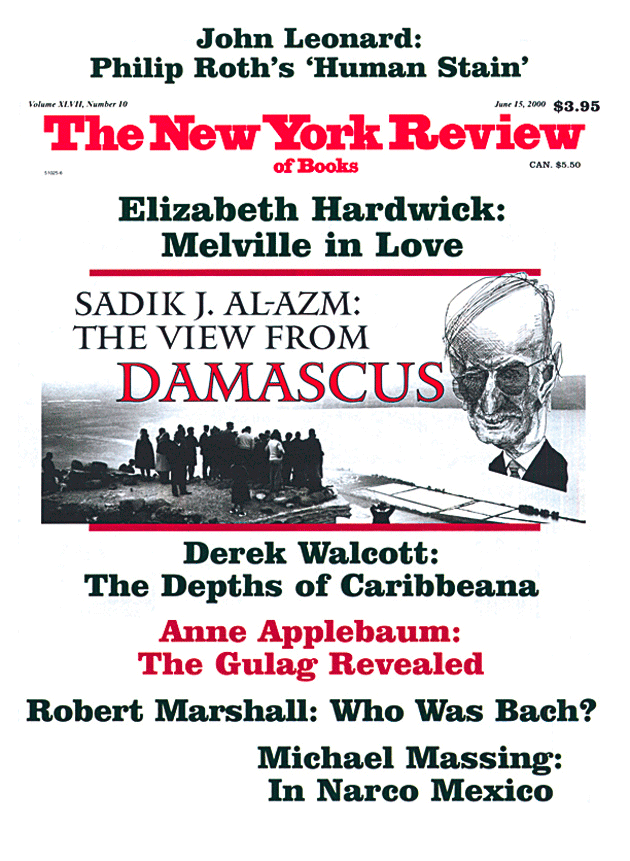

This Issue

June 15, 2000

-

*

To be published by Metropolitan Books, July 2000. ↩