POPULATION MAP OF THE WEST BANK AND GAZA

Before the deluge of the second Intifada, when Israelis and Palestinians were still trying to talk through their differences, they faced three large problems:

1) The future of the Israeli settlements in the West Bank and Gaza, which is tantamount to the future of the borders between Israel and a future Palestinian state;

2) The future of the Palestinian refugees, namely what the Palestinians regard as the right of the refugees to “return” and settle inside Israel;

3) The issue of sovereignty over Jerusalem, and in particular sovereignty over the Temple Mount (Haram al-Sharif).

Many Israelis believed that it was necessary to resolve each of these issues and that if they could be resolved together an agreement could be reached with the Palestinians. If they were to reach such an agreement, the Israelis would also have to accept a Palestinian state and arrive at security arrangements with the Palestinians.

However, the second Intifada has made many Israelis lose faith that there is a Palestinian partner with whom these issues can be negotiated. Even if all three issues are resolved, many doubt the conflict will come to an end. For they now believe that an end to the conflict is precisely what the Palestinians cannot accept: the Palestinian grievance is inconsolable.

Among the three issues, the Israelis find that of the refugees the most threatening. For the Palestinians the basic demand for the refugees’ right of return as well as the issue of the Haram al-Sharif remain unchanged. True, the refugees of 1948 who could still literally return are relatively few and relatively old, but this, in the eyes of the Palestinians, does not diminish their rights or those of their families. The same could be said about the Haram al-Sharif: the sanctuary stands as a rock in a sea of constant changes.

The issue of Jewish settlements is different. It is a dynamic problem that keeps changing as the number of settlers and settlements increases and as the locations of the settlements change. What the Palestinians find most worrying is the increase of over 50 percent in the number of housing units as well as in the settler population since the Oslo agreements of September 1993. In September 1993 there were 33,000 family housing units in the settlements. By July 2000, 19,000 units were added (3,000 of them under Barak). At the end of 1993 there were, according to Israeli statistics, some 116,000 settlers in the West Bank and Gaza. In view of the yearly population growth of 8 percent (natural increase and newcomers combined), we can assume that there were about 200,000 settlers at the beginning of the second Intifada in late September 2000, including 6,500 of them in the Gaza Strip. There are altogether 145 official settlements and another fifty “unofficial” ones. The length of the roads that were built for the settlements, and that are used only by the settlers, increased by 160 kilometers between 1997 and 1999.*

The Palestinians, for their part, regard all civilian Jews living in the territories occupied in 1967 as settlers and all the housing units that were built for them as settlements. In the Israeli use of the terms, the neighborhoods of Jerusalem built on land annexed in 1967 are not called settlements and the people who live there are not called settlers. For the Palestinians, however, some 210,000 Jews in greater Jerusalem are, in their view, settlers as well, and they therefore consider that there are a total of about 410,000 Israeli settlers.

The second Intifada made the settlers the prime moving targets for the Pal- estinian guerrilla attacks—“moving,” since most of the attacks on the settlers take place on the roads. There is a division of labor in Palestinian actions. Those inside Israel are carried out predominantly by the Islamic organizations—Hamas and the Islamic Jihad. Attacks on the settlements are carried out mainly by Arafat’s various military and paramilitary forces. Even if this division of labor is coordinated, it still displays the ideological difference between the Islamic movement and Arafat’s Fatah movement.

Hamas is the main Islamic movement. It was established during the first Intifada, in 1988. It is deeply involved in communal work, including schooling and medical care, and thus presents a moral challenge to Arafat’s corrupt regime. The Hamas leaders are adamant that Israel should be dismantled altogether; the Jews, as “People of the Book,” are entitled to protection once they have submitted to the authority of an Islamic state. The entire land of Palestine, on which Israel sits, is a Waaf—a Muslim religious entity or “endowment,” not to be subjected to any transaction. It is important to Hamas to demonstrate by terror inside Israel that it does not make any distinction between the part of Palestine that is inside Israel and that which is outside: all parts are Waaf. Thus, for Hamas, Arafat’s negotiations over the Temple Mount were an act of religious transgression. As for the Islamic Jihad, it is a small group inspired by the Shiite revolution in Iran and by the Islamic resistance to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. It has no social base and it specializes in suicidal attacks against Jews inside Israel.

Advertisement

One thing is clear: the settlers have been targeted more than others and many of the Israelis killed so far in the Intifada have been settlers. In carrying out the Intifada, the Palestinians have succeeded in making the settlements a central issue. They did not succeed, however, in winning any sympathy for their cause among any significant section of Israeli Jews, not even with those who strongly object to the settlements and the settlers.

The settlers themselves are in a double bind, as soon becomes clear to a visitor to the West Bank. On the one hand they emphasize that for the Palestinians there is no distinction between Netanya, a city in central Israel on the coastal plain, which has been subjected to several terrorist attacks, and the small outlying settlement of Homesh, deep in Samaria. On the other hand, they want to stress their special plight as settlers in a hostile territory. They point out that while they draw most of the Palestinian fire and their lives have become unbearable, other Israelis, as they put it—quoting the hard-liner Uzi Landau, the current minister of internal security—“drink wine and eat cheese” and are indifferent to their suffering. Of course, the blood feud between the Palestinians and the settlers did not start with the second Intifada. During the first Intifada beginning in late 1987, 119 Palestinians were killed by the settlers and their sympathizers. The current Intifada has to a large extent turned into a battle on the roads to the settlements.

With respect to the Jewish settlements, the West Bank, like Caesar’s Gaul, is divided into three parts, or three long strips of land. With a few exceptions, each strip has a different history, a different ideology, and a different type of settler. The first strip of settlements was established in the Jordan Valley (from Kalya, near Jericho, in the south to Mehola in the north). The fifteen settlements there were set up after the war of 1967 and just before the war of October 1973. To develop these settlements the government relied on the traditional Labor Zionist settlement institutions, the kibbutz movement and the moshav movement. The settlements of the Jordan Valley were mostly collectivist settlements in the old style. In the triumphant mood following the 1967 Six-Day War these movements tried to revive their historical mission as the Zionist avant-garde, a mission that had been crucial in creating Israel. The idea was that by creating settlements along the Jordan River, Israel would establish a permanent “security border” there. That the plow, not the sword, would determine borders is an old Labor Zionist article of faith. To install the new settlements, the governments of Levi Eshkol and Golda Meir assigned two prominent ministers who were themselves kibbutz members—Israel Ghalili, a former leader of the Haganah, the clandestine armed organization under the British Mandate, and Yigal Allon, the commander of the Palmach, the striking arm of the Haganah.

The efforts to settle the Jordan Valley coincided with efforts to settle the Golan Heights. The first wave of settlements in both places had the political aim of “maximum security and maximum territory for Israel with a minimum number of Arabs,” i.e., permanently retaining Israel’s territorial gains in places with sparse Arab population. The principle of settling in areas with sparse Arab population was intended to determine where Israelis would settle and where they would not. But the main concern of the effort to establish Jewish settlements in the territories was neither security nor greed but a form of nostalgia, a desire to reenact the pioneering experience of the Zionist frontier. Nostalgia, both invented and real, usually contains the same proportions as a whisky and soda: two parts (invented) to one part (real).

If the idea of settling the Jordan Valley was to bring the kibbutz and the moshav movements back to the forefront of Zionism, it failed. The Jordan Valley settlements, in spite of the huge effort invested in them, did not amount to much. Gilgal has 157 residents, Ro’i 127, and Mehola 302. The ideal of the kibbutz proved to be anachronistic for the purpose of settling the territories.

Since 1979 the driving force in settling the second strip, further west in the Jordan Valley, has been the members of Gush Emunim—the Bloc of the Faithful—whose better-known settlements in the second strip are Beit El (population 3,600), Ofra (1,800), Shilo (1,500), Eli (1,500), and Elon Moreh (1,500). The first of these settlements got a start with some help from Shimon Peres, who was then defense minister in Yitzak Rabin’s first government.

Advertisement

The Gush Emunim settlements were presented as a project of hope, intended to uplift the gloomy spirit that gripped the country after the shattering 1973 war. Politically, the settlements were an act of defiance against the 1967 Allon plan, by which Jewish settlements were not to be established in areas of the West Bank that were heavily populated by Arabs, especially around the city of Nablus, which had about 100,000 residents and has some 200,000 now. Not settling there obviously meant conceding those areas to the Palestinians in any future agreements. But for the Gush Emunim settlers, Greater Israel in its entirety is a “Jewish Waaf,” nonnegotiable forever, and the Gush Emunim settlements are often close to Arab villages and towns. The Gush had strong political allies, not only Menachem Begin and Yitzak Shamir and Ariel Sharon, but, more tellingly, Shimon Peres and Moshe Dayan, who also wanted to destroy Allon’s plan and retain joint control over the entire West Bank with the Kingdom of Jordan.

The settlers of Gush Emunim, for their part, saw themselves as competing with two powerful tendencies: secular Labor Zionism and ultra-Orthodox Judaism. To the secular Zionists they wanted to prove that they, the idealistic religious Zionists, were now taking over the Zionist mission. They would settle the entire “biblical” Land of Israel, replacing the secular movement, which had lost its vitality and whose children had become hedonists living in the present—“nowness”—and lacking roots. The Gush thus aspired to carry on the vital force of the Zionist revolution, and to be the legitimate heirs to the old pioneers of Labor Zionism and the successors of the legendary settlers of Deganya (the first kibbutz, founded in 1909), Nahalal (the first moshav, 1921), and Hanitah (founded in 1938 at the height of the Arab riots, in a region in the Galilee that until then had no Jewish settlements).

As for the ultra-Orthodox, who were largely based in Jerusalem and Benai-Brak and whose lives were devoted to intense religious studies and observance, the Gush settlers wanted to prove to them their superior willingness to make sacrifices in order to fulfill the sacred commandment to settle the Land of Israel. This would show their greater religious intensity, a kind of intensity that the ultra-Orthodox themselves had always found lacking in the cozy modern religious Zionism espoused by the parents of young Gush Emunim zealots.

Behind the Gush Emunim was a religious vision based on the teachings of Rabbi Cook, the Chief Rabbi of Israel between the 1920s and 1940s, as interpreted by his son Zvi Yehuda Cook, who became the spiritual mentor of Gush Emunim. Cook believed that we live at the beginning of messianic times, in which the redemption of the entire Land of Israel is essential for the redemption of the world. Each person, friend or foe, is divinely ordained to help bring about the world’s redemption. According to the Cooks, secular Jews and even Arabs have a “dialectical” part to play in the organic, all-encompassing redemptive process. Thus Jews can live harmoniously with the Arabs (on the Jews’ terms, of course) if only “the left” does not interfere and put wrong ideas in their minds. But since the beginning of the second Intifada talk of harmony with Arabs has stopped. Now what you hear from the Gush settlers is “it’s either us or them”: meaning it is time to get rid of “them.”

Messianic vision certainly inspired Gush Emunim in its early days; and in talking recently to a young couple in a Gush settlement, I heard an echo of this when they told me that they are acting according to a divine plan. And yet I believe the driving force of the Gush Emunim was competition with Labor Zionism to show they are the true heirs of the heroic Zionist tradition. The term “settler” can be expressed by two different words in Hebrew: mitnachel and mityashev. Roughly, the first is one who possesses an inheritance, the second a dweller. The first term, inheritor, has a strong biblical connotation of Joshua’s conquest of the land: “For you [Joshua] shall cause them to inherit the land” (Joshua 1:6). Indeed, this is the term the Israelis generally use in talking about the ideological religious settlers. But for a long time the Gush settlers felt offended by the term “inheritors” and wanted instead to be referred to in the same way as the old Labor Zionists, namely as dwellers. It was not just the Bible that they wanted to inherit, but the legacy of Labor Zionism; they wanted retroactively to participate in the drama of the past, and since they were living in populated Arab areas, the stage seemed set for them to do so.

Not all settlers in this second strip yearn for Zionist legitimacy and care about what Israeli society thinks of them, let alone what the Arabs think. Among them are a group of settlers, including some fairly recent immigrants from the US, who are followers of the overtly racist ideas of the late Meir Kahane. The “bastards” of the settlement movement, they dominate three settlements near Nablus: Itamar (population 440), Yizhar (300), and Tapuauch (700), as well as a part of the Jewish settlement in Hebron. These settlers are wildly aggressive, even by the militant standards of the Gush Emunim. They are committed to a fierce struggle to enlarge the Jewish presence in the West Bank, and I have no doubt that we will hear more from and about them as the conflict continues.

After Begin’s peace with Egypt in 1979 an underground was created among the Gush settlers to stop the withdrawal from Sinai, which meant the evacuation of all the settlements there. They planned a colossal provocation to the Arab world, which would put an end to the peace agreement. The idea was to blow up the mosques on the Temple Mount. The plan failed: a Muslim guard in the sanctuary spotted the underground infiltrators and thwarted their plan. But the underground survived, and after a Palestinian attack on settlers in Hebron, in which five people were killed, the underground retaliated in 1980 by killing and wounding three mayors of Palestinian towns. And three years later, after a rabbinic student was killed in Hebron, members of this underground attacked an Islamic seminary killing three Palestinian students.

The exposure of the underground created a crisis in the settlers’ movement. It seemed to confirm the image of the more militant settlers as a dangerous sect. These days there is open talk in Israel about a new underground among the settlers. This strikes me as plausible. The real question, however, is not if there is—or if there is going to be—another underground among the settlers, but its extent. Will it be as extensive and powerful as, say, the OAS, the horrific French underground in Algeria? My sense of Israeli society leads me to say that, as of now, the answer to this intriguing question is “No.” But things may change and go wrong very rapidly.

The third strip, in which most of the settlers live, is the one closest to Israel’s Green Line, the pre-1967 border. This strip consists roughly of three types of settlers: those who seek a better “quality of life,” those who are economically needy, and those who are both economically needy and ultra-Orthodox. The settlers who seek a better life moved from densely populated cities in Israel into settlements built on scenic hills with red-roofed houses and a garden of their own—all for a relatively small investment. One settlement of that kind is Nili, with 604 largely secular residents, which is next to the modern Orthodox “quality-of-life” settlement of Na’ale. Both are about a forty-minute drive from either Tel Aviv or Jerusalem. For the price of a three-room apartment with two bedrooms in the vicinity of Tel Aviv, a family in Nili can purchase its own six-room house. In some of these communities both secular and religious people live together.

The second type consists of those who are relatively poor and cannot afford to buy an apartment inside Israel. Since there is very little Israeli property for rent, most people buy apartments, partly financing them by mortgages. If a settler buys an apartment worth $100,000, he will receive from the government a standing loan of $20,000, which in practice comes close to turning into a grant after five years. Moreover, he also gets $12,000 as a flat grant; and he pays such low interest on his mortgage (2.5 percent compared to 5.5 percent in Israel proper) that he saves $40,000 in mortgage payments over twenty years. Small wonder then that a settlement of 25,000 residents such as Ma’ale Adimmim near Jerusalem, on the way to the Dead Sea, has many young families that could not afford to own an apartment in Jerusalem.

Someone paid for it, though. According to the government’s master plan for settlements, the establishment of Ma’ale Adimmim in 1974 meant the expulsion of the Bedouin tribe of Jahalin, whose members grazed their flocks there. Some 12,000 acres, the size of Tel Aviv today, were allocated to Ma’ale Adimmim, and more than 25,000 people now live there. Nor do government subsidies stop with money for housing. Living in a settlement like Ma’ale Adimmim (ten minutes from the Mount Scopus campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem) means, among many other benefits, that income taxes are reduced by 10 percent, health taxes by 30 percent, and kindergarten fees by 50 percent.

In comparison to Israelis within the Green Line, settlers are thus doing better economically (or at least they were until the beginning of the current Intifada). For example, 27 percent of Israelis within the Green Line own a personal computer, compared to 48 percent in the settlements. Over 40 percent of the population in the settlements is employed by the state—38 percent in public services, the rest in security—in comparison to the 26 percent of the population of Jerusalem, where all the major state institutions are located. The rate of unemployment in the settlements is nearly zero, as compared with the current overall rate in Israel of about 9 percent.

The ultra-Orthodox settlements are fairly large (Betar Illit, 13,000; Qiryat Sefer, 12,000), and also relatively poor. Most of the residents can’t even afford to buy ordinary apartments in the settlements. They get all sorts of subsidies that the other settlers don’t.

With all the incentives, it is not surprising that the total number of settlers is 200,000. But the yearly growth of the Palestinian population is 150,000. So if the idea behind the settlement project was for the people of Israel “to be increased and inherit the land,” that is, to change the “demographic balance” in the territories, it has failed. In the Gaza Strip the ratio is 1.2 million Palestinians to 6,500 settlers, who nevertheless control 40 percent of the Gaza Strip beach. The settlements in the Gaza Strip are such a moral, political, and military embarrassment that even the right in Israel knows that there is no future for them. By contrast, the suburban settlements in the West Bank just over the Green Line have in effect become incorporated into Israel and few Israelis expect they will be dismantled.

My division of the West Bank into three strips leaves out an important group of settlements—the “Etzion bloc,” located south of Jerusalem on the way to Hebron. It also leaves out the 500 settlers who live inside the city of Hebron, among 120,000 Palestinians, and the mixed secular and religious settlement of Kiriat Arba, whose 6,200 members live next to Hebron. The Jewish settlements in Hebron, established in the late Sixties, were the first in the West Bank, and their militant Orthodox members live in an atmosphere in which they are constantly prepared to encounter and administer violence, a situation that culminated in the murder by Baruch Goldstein, a settler at Kiriat Arba, of twenty-nine Muslim worshippers in the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron in 1994. The settlers of the Etzion bloc are also intensely ideological. They occupy the sites of several kibbutzim in the pre-state period. After the region was conquered by the Arabs in the 1948 war, “returning” to Gush Etzion was one of the first nostalgic goals of the settlement movement.

There are two aspects of the legal status of the settlements: internal and international. In 1977 the Israeli government devised a legal trick to take over the territories for the settlements, citing the Ottoman Land Law of 1855 that enables the military commander of the West Bank territory to proclaim that a particular area is “state land.” Its inhabitants must prove that they are the formal legal owners of the land; if they cannot do so, then the land becomes state land by default. Since less than a third of the land in the West Bank was legally registered and ownership was based on custom, Israel had a legal device for enlarging the 140,000 acres that had been declared state land under Jordanian rule into some 600,000 acres by 1993—about half of the entire West Bank. The practice of “creating,” or in effect confiscating, state land for the benefit of the settlements is not unlike the enclosure of the commons in Britain that awoke Sir Thomas More from moral slumber to write his Utopia.

That the settlements are illegal under international law is not in doubt to any of the 142 members of the UN, except for Israel. Nor is it in doubt to most legal experts, for whom Israel is in violation of Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention (1949), which says: “The occupying power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.” Israel’s legal position is that the territories are not “occupied” since the West Bank was taken from Jordan and the Gaza Strip from Egypt, whose rule over the territories was never recognized internationally as sovereign. The Israelis say the term “occupation” applies only if the territories in question belonged to a sovereign state. Moreover, Israel claims that the words “deportation” and “transfer” in Article 49 were used with the Nazi practice of deportation and transfer in mind, while the Jews settling in the West Bank are not deported or transferred to these territories in any recognizable sense of those terms. But it remains clear that the purpose of Article 49 is to prevent permanent colonization of occupied territories, which is undoubtedly the purpose of the settlements. The rest is sophistry.

A central and much ignored issue in the controversy over the settlements concerns water, always a scarce resource in the arid Middle East. The cause of the biblical wars among shepherds was water. A quarter of Israel’s water supply comes from the Mountain Aquifer system, a layer of underground rock capable of holding a large quantity of water. The aquifer runs 130 kilometers from Mount Carmel in the north to the Negev in the south, and from the Jordan Valley in the east to Israel’s Mediterranean shores in the west. This large system is divided into three subsystems, which provide most of the water used by the West Bank Palestinians. However, the settlements, with approximately 10 percent of the West Bank population, use some 37 percent of the West Bank water, which leaves 63 percent for 1.9 million Palestinians. The water, in the language of international law, is distributed “inequitably and unreasonably.” Even worse is the situation in the Gaza Strip, where the per capita ratio of water distribution for the Israeli settlers and the Palestinians is 7 to 1.

2.

Israelis on both the left and right are talking these days about “separation” from the Palestinians: “We should be here, they should be there.” The left and right differ over where to draw the line between “here” and “there,” but both sides envision that the line will be made of concrete and steel—it will be a security fence, like the one East Germany built in order to separate itself from the West, impenetrable but with border crossings resembling Checkpoint Charlie. For its advocates, the great advantage of this scheme is that it can be carried out unilaterally. The Israelis would not need the agreement of the Palestinians; they can determine their borders as an act of will. This would put an end to the process of creating a binational entity between the sea and Jordan, in which, in a few years, the Palestinians will be the majority. “The Fence” will supposedly protect the Israelis from acts of terror or in any case it will reduce such acts considerably. The settlers who live beyond the fence will be resettled inside the fence. No one suggests a Berlin wall in Jerusalem. But when it comes to Jerusalem, the plans for separation become hazy. One thing, however, is not hazy at all: as the fence is built to cordon off settlements throughout the West Bank, the total length of Israel’s borders will nearly triple.

The ideological settlers are very much against the idea of a fence—they do not want to find themselves beyond the pale. For very different reasons, the idea of separation—as opposed to a Palestinian state with which Israel would have peaceful relations—seems to me an illusion, not least because the fence will put the entire West Bank under permanent siege; as a result, Palestinian resistance is bound to become more violent. What is impor-tant, however, is that Sharon may be tempted by the idea of the fence, and, given his appetites, his fence will include a huge amount of the West Bank. Moreover one has to remember that Sharon, more than anyone else, was the prime mover in building the existing settlements as the minister in charge of the occupied territories in the Begin and Shamir governments. He has talked of 42 percent of the West Bank being allotted to the Palestinians, the rest to Israel—a huge expansion of Israeli territory.

Central as the issue of the settlements is now, it was not disagreement over this issue that broke down the negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians. The two sides were close to resolving their differences at their meeting in January 2001 at Taba in Egypt, five months after the end of the Camp David summit. At those talks, there was an implicit understanding that the settlements issue will not be resolved unless a clear distinction is made between the settlements and the people who live in them. Over 50 percent of the settlers live in the towns that are close to the Green Line. If Israel annexed 3 percent of the West Bank while giving up an equal amount of the land it controls in Gaza, more than half of the problem of the settlers would be solved.

That solution, which seemed a possible basis for agreement at Taba, would have meant abandoning most of the settlements. Their residents would have to be resettled inside Israel or in the remaining West Bank settlements, preferably in communities that can provide them with jobs. Traveling recently in the West Bank, I met two settlers on the road to Yakir. One of them said: “You guys should stop blaming us. We are here because every Israeli government told us that here is where we should be. We are obedient citizens, and if we are told to leave, we’ll leave. All we ask is to be offered a respectable solution.” I believe most of the settlers—who are driven neither by nostalgia nor ideology—would agree with them. A “respectable” solution can and should be offered to all the settlers. As for the settlers who reject such a solution, many will fiercely resist and threaten a civil war.

Talking with Palestinians, I have found that some of them have their own idea of reciprocal sacrifice. We know, they say, that at some point we will have to give up on the return of the refugees. But we want Israel to pay for this with a “refugee problem” of its own—the problem that will arise when the settlers have to leave their homes and become, in effect, refugees themselves. This will give the Israelis a glimpse of what we Palestinians went through. But it would not be exactly tit for tat, since our expulsion from Palestine is much worse than any difficulty you may have in absorbing settlers.

This is a view that can be found among Palestinians who believe that they should come to terms with Israel. But what some of them have in mind is total evacuation of the settlers from the West Bank and Gaza, including the many settlers in the towns close to the Green Line. This is not a sentiment that is conducive to the idea of a land swap. It is a matter of settling scores, or at least some scores. In my view a solution should avoid unnecessary pain, even for people who shouldn’t have settled in the conquered territories in the first place. And such a solution, I believe, could be worked out along the lines of the land exchange discussed at the Taba meeting, provided that such an exchange would be an acre-for-acre swap. But this does not mean that the current leaders on both sides are genuinely concerned to find a peaceful solution. The question is when they, or subsequent leaders, will seriously seek one.

—August 22, 2001

This Issue

September 20, 2001

-

*

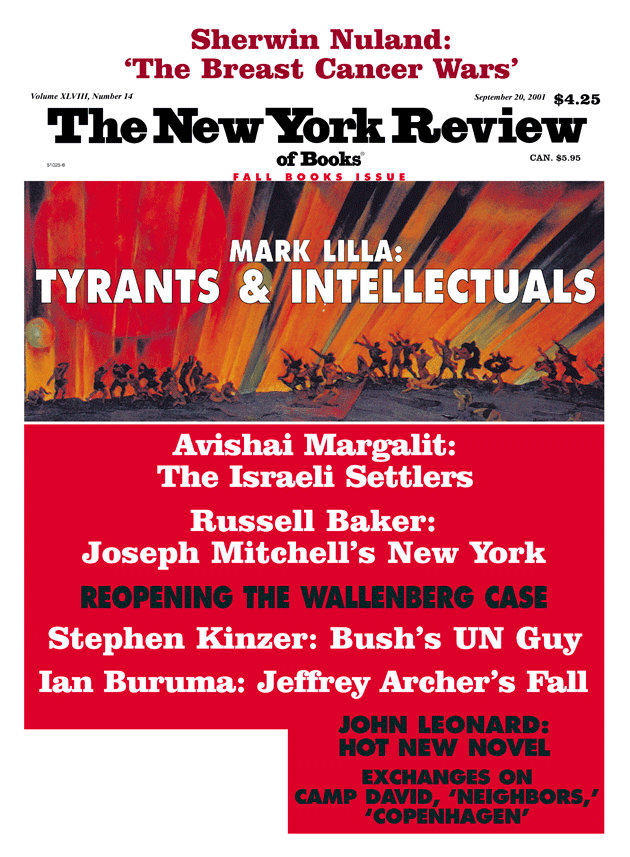

The best sources of information on the settlements are the Statistical Abstract of Israel and the reports of the Settlements Watch Team of Peace Now and the B’tselem human rights organization. Peace Now and B’tselem are regarded by the right as suspect, but I have not encountered any significant factual claim by Peace Now or B’tselem that has been successfully contested. In fact, the population map prepared by Peace Now in November 2000 (see illustration) is the one many government officials grudgingly use. ↩