The ground bass of the great Irish melody is complaint. Successive waves of invasion by Celts, Norsemen, Anglo- Normans, English, have allowed us in Ireland always to lay the blame for the ills that beset us upon the Other; upon, indeed, a rapacious host of Others. Hence the acronym employed recently by the journalist and critic Fintan O’Toole: MOPE, that is, Most Oppressed People Ever. Yet as the historian Joseph Lee has pointed out, very many countries—for instance, in Eastern Europe during and after World War II—have suffered far worse injury to their populations and infrastructures than Ireland ever did, yet managed not only to survive, but to heal themselves and, in numerous cases, to thrive.1

This is not to say that Irish plaints are unjustified, as a glance at the history books, at least the unrevised ones, will amply demonstrate. In the closing decades of the sixteenth century the suppression by Elizabeth’s distinctly unsad captains of the Desmond rebellion in Munster left all of Ireland below a line drawn between the cities of Cork and Limerick, an area of lush land half the size of Belgium, utterly laid waste and depopulated. In their drive through the countryside the English conquistadors left nothing and no one standing. Sir William Pelham, one of the commanders, put it succinctly: “We consumed with fire all inhabitations and executed the people wherever we found them.”

It was an irony not lost upon the Irish that the rebel Earl of Desmond, whose defiance of the Crown had called down such destruction upon the land, was Gerald FitzGerald, direct descendant of Anglo-Norman robber barons who four hundred years previously had come over from Wales to stake their claim to the rich Irish territories of the southeast, preparing the way for the annexation of Ireland by the English King Henry II. Indeed, while the Desmond wars raged, the last of the native Irish lords, Hugh O’Neill of Ulster, according to his biographer Seán O Fáolain, “lay doggo in the north, purchasing the confidence of the English either by actively assisting them to butcher the south, or by his cautious inaction.”2 Heaping irony upon irony, we may point out that Desmond himself had spent much of his early life in the great houses of England, for the most part unhappily, although he had been the playmate of princes.

As Declan Kiberd points out in Irish Classics, “Most of the [Irish] lords in the later 1500s had little sense of the [English] invaders as representatives of a modern nation: for them the Tudor forces were just a foreign element, another in the seemingly endless sequence of constants from the dawn of time who fought for control of land.” It was left to the filí, the court poets, to recognize, or at least to sense, the slow earthquake that would eventually swallow the Gaelic world and its ways. Among the first tremors of that catastrophe was the introduction by Henry VIII in 1541 of the ingenious, and perfidious, system of “Surrender and Regrant,” whereby the Irish chiefs would give up their lands to the English Crown in return for so-called privilege and protection, while the lands would be immediately granted back to their owners, under certain subtle conditions which ensured greater English influence. The Irish, locked among themselves in endless feuds and territorial squabbles, were too short-sighted, and too contemptuous of outsiders, to see the trap that had been laid for them. The poets, however, managed a longer view. Kiberd writes:

As primogeniture took the place of Gaelic custom, the notion of the poets as interpreters of rightful sovereignty became redundant. No longer could the filí record the beneficence or otherwise of a man’s rule; no longer would he offer the rod at the investiture of the tánaiste named by a sept to succeed a dead lord, for now primogeniture was the iron rule. No wonder that after the decree of 1541 (which had to be read in Irish by the Earl of Desmond at the Dublin Parliament), the more alert among the poets sensed the long-term implications of such anglicization.

The bardic order, an aristocratic one, had held an extraordinarily powerful position in the ancient Irish world. “They stood,” according to Kiberd, “second only to the chieftain in the pecking order and might even wield power over him: for it was their duty not only to praise a wise and generous ruler…but also to denounce a bad leader….” Such “power to the poets” may seem incomprehensible to the outside world, but in Ireland the word, spoken and written, is and has always been supremely potent. If the versifiers are no longer the anointers of kings—a thing devoutly to be thankful for, some will say—the wordsmith can still attract a rapt and gullible audience.

Advertisement

“Words,” writes Kiberd, glancing back through Ireland’s troubled history, “were the only weapons available to a disarmed people who had sought, over centuries, to expose the difference between official pretence and actual reality.” That is, if you like, the positive aspect of the Irish way with words. There is a less grand, less tragic aspect. In the past decade or so, many public figures in Ireland, politicians, businessmen, church leaders, have been revealed to be corrupt and depraved. The uncovering of each new enormity has been greeted by a public outcry of shock and reprobation, but louder still has been the demand for an explanation, for an account of how and why and when—for, in other words, the story. So it is that after months of tribunal hearings, court cases, public confessions, we often cannot rightly tell which we are passing judgment on, the actions of this or that mendacious politico, venal tycoon, peccant prince of the church, or the skill with which he—and the lineup has been almost entirely male—has framed his defense. Words alone are certain good, Yeats declared, but was he right? The gab can be a dubious gift.

The central argument of his book, Kiberd declares, is that for the Irish writer of antiquity no less than of the present day, “to be Irish was to be modern anyway, whether one liked it or not.” Thus in the early, and best, chapters, dealing with the ancient poets, those dying generations, he constantly refers forward to their descendants, as he sees them, of later times, including our own. He opens the chapter “Dying Acts” with a grimly ringing declaration: “Every sentence is a death sentence, in the sense that every statement is no sooner begun than it is already starting to die on an exhalation of the breath.”

After that sober beginning, and although the main subject of the chapter is the “‘last’ great poet of eighteenth-century Ireland,” Aogán Ó Rathaille, it is not a surprise to come quickly upon the name of Samuel Beckett. Remarking on the “last words” convention, “a vestige of the old bardic arrogance,” whereby Irish poets saw them-selves as giving witness from their boat upon the Styx to the collapse of a civilization, and “affected to write the account of their own death even as they underwent it, so that teller and tale would finally be one,” Kiberd points out:

In his later, more anorexic writings, Beckett would develop a voice very close to that of the Gaelic bards: his protagonist would lie on his back in the dark, summoning voices, working on a set exercise. Invariably, he would offer to do something rather strange: both to die and in the very act of dying narrate an account of his own passing. Malone Dies is the classic text.

In this and many other instances of trans-temporal connection, Kiberd reinforces his statement of intent, to present Irish literature, and, by extension, Irish culture in general, as contemporaneous, all of a piece, and thoroughly modern. Kiberd, Professor of Anglo-Irish Literature at University College, Dublin—the alma mater not only of the cosmopolitan James Joyce, but also of Patrick Pearse, ultranationalist leader of the 1916 Rising—is a Catholic, and springs from a liberal nationalist tradition, if “liberal” and “nationalist” are words that may credibly be forced together. He is here to praise, not to bury. His big, freewheeling book is a celebration of the indomitable liveliness, in the strongest sense of that word, of Irish literature.

His critical inclusiveness is admirable in these days of fragmentation and special pleading, but his relentlessly positive argument can be wearing over the very long distance that he covers. As if loath to speak ill of his own before strangers, he repeatedly saves face for Irish writers, passing off failures of sensibility or technique as cunning effects of artistry. An example taken almost at random is his contention in the case of the Irish novelist Kate O’Brien: “Even the weaknesses of O’Brien’s art are flaws she appears to share with [George] Eliot.” In that “appears to” the weasel shows its glinting tooth.

All the same, there are instances of startling revelation, or at least instances of startlement that seem revelatory. In a splendidly vigorous chapter, he manages to claim Edmund Burke, “a dishonoured Irishman smouldering with the unappeased anger of one who went to a hedge school in Cork and never forgot it,” for the Irish revolutionary nationalist camp, insisting that his rebellious sympathies were only suppressed “because he was by nature a reformer.” What really lifts the eyebrows, however, is his comparison between Burke the High Tory and the old poets of the aisling, that overused convention by which a long-suffering Ireland appears in the poet’s dream as a ghostly, beautiful, and much put-upon young woman:

Advertisement

Whether the subject was England, India or France, the threat to national sanctity and loveliness was evoked by Burke in the image of a ravaged womanhood. In his Reflections on the Revolution in France, he describes how Marie Antoinette fled from a royal palace in which no chivalric hand was raised to defend her: “I thought ten thousand swords must have leaped from the scabbards to avenge even a look that threatened her with insult….” It wasn’t hard for Burke to cast himself in a role made familiar by dozens of aisling poets, evoking a defenceless spéirbhean (skywoman) who would only recover happiness when a young warrior rallied to her defence.

Elsewhere, Kiberd leans rather heavily on the reader’s credulity. In his chapter on Oscar Wilde he remarks on the manner in which Wilde’s aphorisms have “become part of the folklore of modernity,” and suggests that Wilde’s children’s stories—for which Kiberd makes what are surely over-large claims—“have re-entered the Irish tradition through the astonishingly similar childhood parables of Patrick Pearse”:

Pearse’s story “Íosagán” has obvious roots in [Wilde’s story] “The Selfish Giant,” with its idea of a Christ-child bearing redemptive messages to a fallen adult world. Indeed, it would not be fanciful to suggest that the mentalité which lay behind the Easter Rising of 1916—that he who loses life will save it by a Christlike combination of goodness and social rebellion—is traceable to this thinking. Pearse was hardly the only rebel who had been moved by the tales of Oscar Wilde, which saw in Jesus a conflation of artist and rebel, scapegoat and scapegrace.

This is hair-raising stuff, particularly piquant, too, in light of the muffled speculations that sometimes rise to hearing in regard to Pearse’s own sexual proclivities. One strains to hear poor Oscar’s ghost, echoing Yeats, and wondering, “Did that play of mine send out/Certain men the English shot?”—Lady Bracknell as the goddess of war, perhaps. Encountering such a passage, the picture forces itself forward of Kiberd merrily at his desk, grinning in wicked satisfaction and murmuring into the shocked air of his study, “Well, historical revisionists, what do you say to that?”

The first five chapters of Irish Classics are devoted to Irish-language writers, mainly poets. Kiberd’s attitude to Gaelic seems ambiguous. He wonders if the “very brilliance of the English-language literature of Ireland may be a direct consequence of the reported loss of Irish, a massive attempt at psychological compensation.” But as that modifying “reported” indicates, he does not consider the Irish tongue to be dead, although even he would not deny that it has almost entirely fallen out of use as a mode of social communication. He contends that the collective decision of the Irish people after the catastrophic famines of the 1840s to turn their backs on the Irish language and speak English instead was an “immense intellectual achievement,” which later nationalists should acknowledge. This will without doubt enrage those very nationalists and their natural allies, the gaelgoirí, fervent Irish-language revivalists much despised by the “modernizing” Irish.

Kiberd is tolerant of figures such as the academic and teacher Daniel Corkery—although, come to think of it, Corkery was sui generis—those fierce, hidebound, isolationist intellectuals who played such a large and, some would suggest, lamentable part in the making of the Irish Republic in the decades after 1922. He quotes Corkery’s insistence—this was in 1941, in some of the darkest days of the war between England and Germany, toward which Ireland maintained a fastidiously neutral stance—that “the English language, great as it is, can no more throw up an Irish literature than it can an Indian literature [so much for Rushdie et al.]. Neither can Irish nationality have its say in both English and Irish.” Kiberd goes on, however, to consider the Belfast Agreement of 1998, in which, contra Corkery, Irish nationality can have its say in Irish and in English: the agreement stipulates that citizens of Northern Ireland may legally consider themselves Irish, British, or both, which means that Northern Irish people can not only carry two passports, but may vote in elections to four parliaments, in Belfast, Dublin, Westminster, and Strasbourg.

Like Irish writers ancient and modern, each of whom “had to cope, in his or her way, with the coercive onset of modernity,” the still shaky Belfast Agreement, according to Kiberd, has “generated a narrative that seeks to salvage something of value from the past, even as the forces of the new world are embraced,” and is couched in language “richly indebted not just to postcolonialist theory and to recent forms of Irish criticism,” but to writers such as Charlotte Brooke and Maria Edgeworth. Of course, and incidentally, Kiberd the self-declared feminist is here no doubt being a touch disingenuous in choosing to adduce as examples these two minor, female, figures.

3.

Edna Longley, in Poetry & Posterity, also ranges beyond Irish poetry, considering not only the Belfast Agreement and the current state of Northern Ireland, but also wider questions of the present historical moment, in particular ecological issues. In her closing paragraph she makes a risky declaration: “Some people read Irish history as poetry. I prefer to read poetry as history.” This will make her seem a far more politicized, engagée critic than in fact she is: the times are such that all of us in Ireland are at one time or another goaded into extremes.

Longley is a southern Irish Protestant who has lived for most of her adult life in Belfast—she is married to the poet Michael Longley—and is Professor of English at Queen’s University, Belfast. If Declan Kiberd is a liberal nationalist, it would be nice, from the point of view of symmetry, if Longley could be described as a reluctant unionist. However, nationalist– unionist is not the only available dichotomy in Northern Ireland. Certainly Longley is resistant to the ex-clusive claims to racial authenticity and historical certainty which even the most liberal nationalists are prone to make. Her own voice, especially when she is speaking at what Lionel Trilling called the “bloody crossroads” where politics and literature meet, is firm, subtly inflected, and stubbornly outspoken:

Clan loyalty (say nothing in front of outsiders) is the Irish version of cosiness and blandness. Pernickety criticism, like scruples about colonialism, would be bad for literary trade and literary tourism.

She quotes approvingly the critic Joep Leerssen’s definition of “Celtic” as “the history of what people wanted that term to mean,” and casts a leery eye on the queasy, religiose imagery in which ultranationalism indulges: “One of the fascist kitsch Sinn Fein murals in west Belfast includes Celtic tracery, a dolmen, Cathleen ni Houlihan wearing a green monk-like robe, and a dove that looks like an eagle.” She is clear-sighted and brisk on the Northern predicament:

The impasse between Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland seems insoluble because it is proleptic. Each group’s politics vault to the desired or dreaded finale. The end paralyses the beginning. For republicans, the end is the goal: “Our day will come”: the day of British withdrawal when history can at last begin. For unionists, that same day figures the end of history as a terrible terminus.

Lest these quotations from a long and intricately argued book give the impression of an overemphasis on politics, it should be emphasized that Longley is, before anything else, a literary critic in the soundly old-fashioned sense. If Kiberd’s large volume reads like a textbook for a freshman course in Irish literature, Longley’s is more redolent of the postgraduate seminar. This is not to slight either critic, or to set one above the other. Their aims are widely divergent, and both achieve a very great deal. And it is not their fault if their books inevitably position themselves against each other: Kiberd Catholic, free-ranging, relaxedly accommodating; Longley Protestant, resistant, fastidious, and fierce. These may sound like clichés, but in Ireland clichés can have all the power of fresh-minted insights. It should be pointed out, however, that both are amicable colleagues in academe, and indeed have collaborated in a recently published pamphlet on multiculturalism and Ireland.3

Longley insists, like Kiberd, on inclusiveness as against special pleading for this or that cause or minority. Her brand of “pernickety criticism” would not be welcomed in the groves of so-called “cultural studies.” She is particularly stringent in regard to those Irish poets who have set out westward to make a reputation for themselves. In the chapter “Irish Bards and American Audiences,” she upbraids those American queen-makers who have taken the poet Eavan Boland uncritically at her own word, “blandly accepting Boland’s identification of her own precursors as Emily Brontë, Emily Dickinson and Sylvia Plath.” She caustically observes: “That, surely, is for the critic to establish with reference to specific effects in the poems. Will anyone be more impressed by this essay if I identify my precursor as Aristotle?”

Overall, Longley is something of an anti-Modernist, or at least she maintains a healthy skepticism in the face of Modernist claims to revolutionary originality, as a glance at the contents page of the excellent Bloodaxe Book of 20th Century Poetry, which she has lately edited, will indicate.4 For instance, she makes a grudging selection of three pieces by T.S. Eliot as against six by Ivor Gurney—and includes nothing by Ezra Pound. She is a champion of neglected English poets of the early twentieth century such as Edward Thomas, editions of whose poetry and prose she has edited. Her chapter here on Thomas, “The Business of the Earth,” is timely and illuminating, and peculiarly moving:

Thomas’s poetry destabilises authority, perception and time in a spirit often regarded as peculiar to modernist aesthetics. It does so with precise reference to environmental and epistemological issues latent in his immediate historical context. And it exhibits a kind of historical imagination usually precluded by the premises of American and Irish modernism.

Yet she is aware also of the dangers of pastoral as a too-easy province of poetry. In her chapter “Pastoral Theologies,” she is cool, but also acknowledging, about the poetic quality of what she identifies as the pastoral of the Irish West of Galway, Sligo, and the Aran Islands:

In Gaelic and English, in prose and drama, in the visual arts and cinema, in tourism and postcards, in politics and ideology, in pilgrimages, fashion, oyster festi-vals, poetry festivals and summer schools, the West continues to generate meanings. Meanwhile, Irish poetry itself is still sifting Yeats’s original aromatic blend of Ossian, mysticism, aestheticism and Co. Sligo, still unmaking and remaking the Yeatsian West.

She criticizes Declan Kiberd’s judgment, in the controversial 1991 Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, of which he was one of the editors, that Yeats’s enthusiasm for Sligo—for its language and people—was a “refusal of history” deriving from Protestant guilt. And she takes issue with Kiberd’s castigation of the number of poems by Irish writers “set on the Aran Islands, or in west Kerry, or on the coast of Donegal—all written by artists who act like self-conscious tourists in their own country.” Longley points out that there is also an equally strong anti-western pastoral, notably in the work of Joyce. Kiberd, she writes,

implies that Irish Catholics [she means writers] should/can never imaginatively travel in Ireland since they already belong to the single transferable national place: the universal parish or geographic collective. Hence the contrary image of Irish Protestant writers as literary playboys of the western world. Kiberd reads contemporary poetry according to a historical prejudice. The charge of tourism, like the charge of aesthetic or scientific detachment, imputes a suspect outsider (at best), colonial (at worst) status.

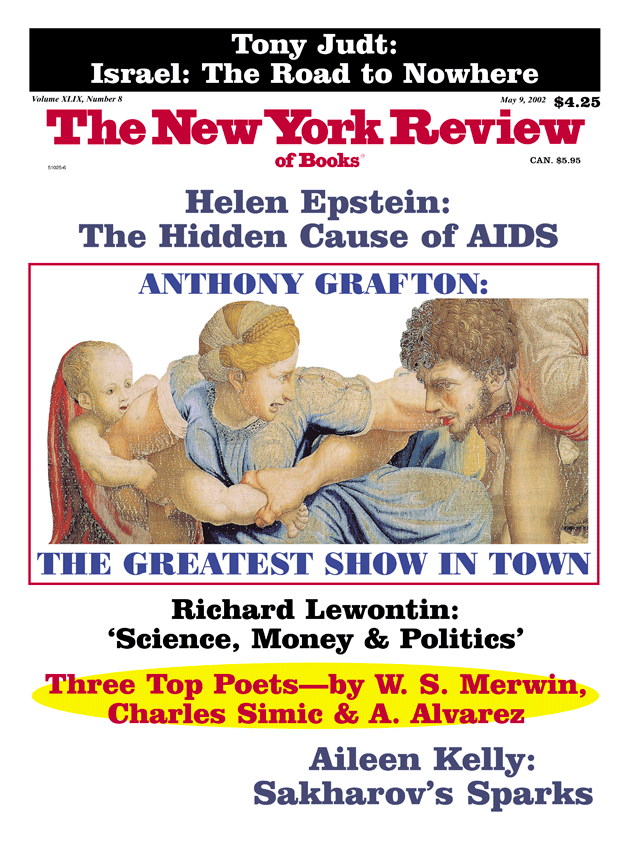

Considering the “northern pastoral poetry” of Patrick Kavanagh, Seamus Heaney, and John Hewitt—the latter one of her particular enthusiasms—she remarks wryly on the fact that the cover of Kavanagh’s Selected Poems in the Penguin edition bears as cover illustration a western landscape by the painter Paul Henry, “evidence that, from London, all Irish literary countryside looks the same.” By a nice twist of irony, the jacket of the Harvard edition of Kiberd’s Irish Classics is also adorned with one of Henry’s somewhat kitschy canvases, Spring in Connemara. Authors should not be held responsible for the choices made by a publisher’s design department, but one cannot resist comparing Kiberd’s alluringly cozy cover with that of Poetry & Posterity, which is adorned with a rollickingly bibulous set-piece by Jan Steen, Rhetoricians at a Window.

Both critics, however distinct their voices, address the same Ireland, in which the Celtic twilight mists have not yet entirely dispersed—note, for instance, the markedly frequent recurrence in both the books of the word “liminal,” and of the repeated, wistful conjuring of the figure of the “Tory Anarchist” with whom, it seems, a disaffected Irish Jacobin might make common cause. In the matter of Ireland, one sometimes despairingly—mopingly?—feels that while everything changes, all remains the same. Even Edna Longley can sometimes seem concerned less with posterity than with the past. Kiberd chides Patrick Kavanagh for taking the laments of the bards too literally in his poem “Memory of Brother Michael,” “failing to notice the strange energy of the language in which they were made,” yet anyone looking at the state of Ireland past and present will feel a responsive twinge before Kavanagh’s merry savagery:

It would never be morning, always evening,

Golden sunset, golden age—

When Shakespeare, Marlowe and Jonson were writing

The future of England, page by page,

A nettle-wild grave was Ireland’s stage.

It would never be spring, always autumn,

After a harvest always lost,

When Drake was winning seas for England

We sailed in puddles of the past,

Chasing the ghost of Brendan’s mast…

Culture is always something that was,

Something pedants can measure,

Skull of bard, thigh of chief,

Depth of dried-up river.

Shall we be thus forever?

Shall we be thus forever?

This Issue

May 9, 2002

-

1

J.J. Lee, Ireland, 1912–1985: Politics and Society (Cambridge University Press, 1989). ↩

-

2

Seán O Fáolain, The Great O’Neill: A Biography of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, 1550–1616 (London: Longmans, Green, 1942; Mercier Press/Dufour Editions, 1997). ↩

-

3

Edna Longley and Declan Kiberd, Multi-Culturalism: The View from the Two Irelands (Cork University Press, 2001). ↩

-

4

The Bloodaxe Book of 20th Century Poetry: From Britain and Ireland (Bloodaxe Books, 2000). ↩