1.

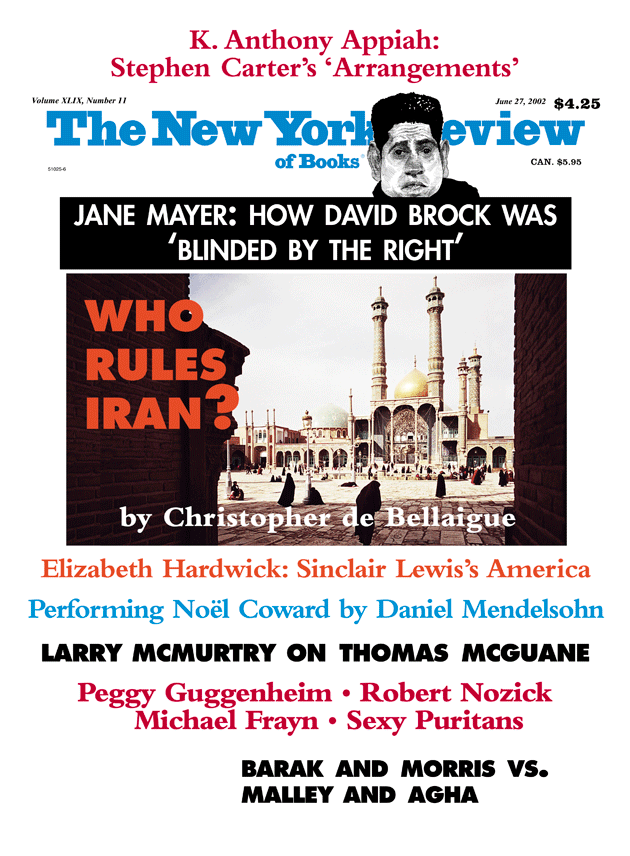

The Shia seminary town of Qom, seventy-five miles south of Tehran, is bleak and set in semi-desert, with a dried-up river going through it. It has few orchards; it is not renowned for any fruit or pickle. Most of the vegetables you find here have traveled long distances. The townspeople produce a sickly caramel, sometimes embedded with shards of pistachio, called sohan. To escape the soporific effects of the heat the seminarians work in subterranean libraries. In the case of bachelor scholars, widows and impoverished women attend to their physical needs. Some people have likened Qom to Oxford or Cambridge, for the seminarians wear black gowns and inhabit cells inside brick-built colleges that look in on themselves. There, the resemblance ends. Never in English history were the universities as mighty as the seminaries of Qom are today.

Qom rose to prominence as a modern seminary town after Britain seized what is now Iraq from the Ottomans at the end of World War I. When the clerics of Najaf, an important Shia shrine town in southern Iraq, incited revolt against the British, they were expelled; some of these clerics ended up in Qom, which a prominent ayatollah was reviving as a center of religious learning. Qom’s development was still not assured; from 1925, the Shah of Iran, Reza Pahlavi, regarded Islam in general and clerics in particular as hindrances to his efforts to modernize Iran. He introduced military service for some clerics and banned all but the senior clergy from wearing the traditional gown and turban. He came to Qom to horsewhip a senior ayatollah who had criticized the Queen’s immodest mode of dress.

Clerical resentment of the monarchy increased under Reza’s son, Mohammad Reza, but the theologians of Qom were divided on whether Islam required that they actively oppose tyranny or concentrate on their primary duty: studying Islamic law and transmitting it to believers. In the 1960s, the activists came under the influence of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini; and in 1979, after the Shah fled and Khomeini returned from exile to set up the modern world’s only clerical state, Tehran was its capital but Qom was its heart.

Since then, Qom has been booming. The clerical population has risen from around 25,000 to more than 45,000, and the nonclerical population has more than tripled, to about 700,000. It is very hard to calculate the vast sums of money that flow, in the forms of alms and Islamic taxes, to Qom’s ten senior ayatollahs—called “Objects of Emulation” because their fellow clerics have pronounced them qualified to act as models whose behavior and rulings laymen and lesser clerics can follow. (Every believer is free to choose the “Object of Emulation” he or she admires most, whether they are inside or outside Iran.) These donations, along with state help for favored institutions, have pushed up the number of seminary schools in Qom to fifty-odd, and the number of research institutes and libraries to around 250. These institutions produce hundreds of books and journals every year, and they use the Internet to disseminate and publicize their findings on subjects like Islamic law and history, philosophy and political economy. The municipal council is buying and destroying buildings that stand in the path of a grand boulevard that has been projected to lead from the shrine of the sister of one of Shiism’s twelve imams to a grand modern mosque five kilometers away.1

After the revolution, a highway was laid between Qom and Tehran, making it easy for politicians and bureaucrats to go back and forth; if you have a reckless driver, the trip from south Tehran will take you barely an hour. This spring, Syria’s foreign minister, on a visit to Iran, made an unpublicized nocturnal trip to Qom; he wanted clerical support for his request, prompted by the US and Lebanon, that Iran downgrade its relations with Hezbollah. (He got an ambiguous answer.) The intelligence ministry is said to have consulted clerics in Qom on the wisdom of exploring better relations with the US. (Here, too, the response was vague; Bush, who included Iran in the “axis of evil,” has alarmed many clerics, but some have warned against giving the impression that Iran is buckling under pressure.) If the US brings down Saddam Hussein, the thousands of Iraqi clerics currently in exile in Qom will have a strong influence on their country’s future.

The word “Qom” has come to stand for the nationwide clerical establishment, since other seminary towns are subservient to it; and the influence of Qom is particularly evident at the center of power in Tehran. Iran’s Supreme Leader, its president, parliament speaker, and top judge are clerics. So are both the head and half the members of the twelve-man Council of Guardians, the powerful monitoring group whose clerical members are appointed by the Supreme Leader; it acts, in effect, as the upper house of parliament and can annul legislative acts. A significant minority of the thirty-eight members of the Expediency Council, appointed by the Supreme Leader to resolve disputes between parliament and the Council of Guardians, are clerics. The Assembly of Experts, which chooses, appraises, and can, in theory, dismiss the Supreme Leader, is made up of eighty-six clerics who have been elected by universal suffrage—but only after candidates first have been vetted by the Council of Guardians. Although most provincial governors are not clerics, in each province the assent of the Supreme Leader’s representative, invariably a cleric, is required for most of the important decisions he makes. The same is true of the heads of universities.

Advertisement

Lower down, clerical dominance is less institutionalized, but nonetheless striking. The thousands of seminarians who leave Qom after completing the six years of study that generally qualify them to wear the clerical gown and turban have a head start in the race for jobs in the bureaucracy. Their children tend to be granted places at the best schools. If they are suspected of breaking the law, they are tried by other clerics, usually behind closed doors. In some parts of the government and bureaucracy, such as the judiciary, an old-boy network favors appointments from particular seminaries. The senior echelons of the intelligence ministry and judiciary contain many graduates from Qom’s Haqani seminary.

Although the revolution has made the clerical calling more powerful and more privileged, not all clerics have been happy about this. Far from bringing about the end of the old debate over clerical involvement in politics, Khomeini’s revolution intensified it. At the revolution’s outset, most of the half-dozen “Objects of Emulation” who were living in Iran and Iraq either opposed the principle of clerical rule or remained silent about it. Qom’s subsequent resistance to attempts to impose on it a uniform reading of political Islam has much to do with the pluralistic tradition of the seminary. Seminarians are free to join the study circles of the “master” they most admire. He can teach pretty much what he wants, provided he does not disseminate contentious views outside the seminary.

For the past decade, the prestige of the clerics among most Iranians has been falling. This is clearly illustrated by the decline in clerical representation in parliament. In the first parliament after the revolution, clerics made up 51 percent of the total number of deputies. They now make up 12 percent. In the early 1980s, clerics were generally treated with elaborate courtesy. Nowadays, clerics are sometimes insulted by schoolchildren and taxi drivers and they quite often put on normal clothes when venturing outside Qom. Some are willing to give up the official privileges that, they believe, cause the public to resent them. I talked in Qom to clerics who said there was now increasing sympathy for Abdolkarim Soroush, a brilliant lay theologian and philosopher who argues that religion must sever its links with worldly power if it is to retain its authority. Far from improving the status of the clergy, these clerics say, involvement in government has debased it.

A small but important part of George Bush’s “axis of evil” speech seemed aimed at these clerics. In Tehran, people thought it was crass of the US president to lump Iran together with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq; they remember when America sided with Saddam during the Iran–Iraq War of the 1980s. Some quite unconvincingly professed astonishment at Bush’s suggestion that Iran sponsors terrorism and is trying to produce weapons of mass destruction. In Qom, however, reactions were more concerned with the US president’s observation that “an un-elected few repress the Iranian people’s hope for freedom.” Although Bush was referring to Iran’s malfunctioning democracy in general, his comments recalled to many people the continuing influence of the Ayatollah Khomeini and particularly the political sectarianism that Khomeini used to entrench clerical rule: “the guardianship of the jurist.”

As early as the late 1960s, Khomeini was putting forward a novel interpretation of Shia doctrine, defending a rudimentary version of the kind of religious government he eventually installed. Using deductive reasoning and a tendentious interpretation of the sayings attributed to the Prophet and the twelve imams, Khomeini argued that religious government should not be allowed to lapse simply because there were no imams to provide it.2Instead, he said, Shiism’s leading clerics, the senior scholars of Islamic law, should assume judicial and executive authority, pending the return of the twelfth imam.

The “guardianship of the jurist” proposed by Khomeini can be understood as an expansion of the “guardianship” that Islam proposes in the case of orphaned minors, with the whole Islamic community in the role of orphan and the ruling jurist in the role of the adoptive parent. On his return from exile, following the Shah’s flight in 1979, Khomeini said he was invoking “the guardianship that I have from the holy lawgiver [the Prophet]” to appoint an interim government. He announced that opposition to this government would be “blasphemy.”

Advertisement

Khomeini, many people believe, may have abhorred electoral democracy; but he was forced to compromise with nonclerical Islamists who had been influenced by modern democratic notions. According to Daniel Brumberg, the author of a meticulous examination of Khomeini’s legacy,3 the 1979 constitution, which turned Iran from a monarchy into an “Islamic republic,” was “an ideological mishmash …probably unmatched in the history of constitutionalism.” It provided for the direct election of a president and a parliament, and separated the legislative, judicial, and executive branches. But it made all officials answerable to the appointed Supreme Leader and made no clear provision for the settlement of disputes between the elected lower house of parliament and the appointed upper house, the Council of Guardians. The constitution was marred by what Brumberg describes as a “chaotic division of powers” between different institutions and organs of government, and it was silent on how these competing institutions should coexist. According to some articles of the constitution, sovereignty belonged to God; but the principle of holding elections suggested a recognition of popular sovereignty as well.

Khomeini dominated the patchwork government of Iran until his death in 1989. He alone had the theological expertise, political flair, and popularity that he himself had laid down as criteria for Islamic leadership. Sometimes contemptuous of Western-style elections, he could claim that he had a popular mandate, illustrated by the vast numbers of people who greeted and visited him after he returned from exile. This reminds Baqer Moin, his excellent biographer, of a pledge of allegiance.4 Khomeini’s appeal was exploited by his entourage. They attributed to him a pseudo-divinity that, in turn, endowed his pronouncements with binding authority, allowing him to interfere in public life wherever he wanted. Khomeini was able slowly to discredit a very senior dissident ayatollah, Kazem Shariatmadari, even though Shariatmadari’s theological standing was equal to his own. A word from Khomeini obliged the Council of Guardians to lift their veto on any law he favored. His “decree” led to the execution, without due process, of thousands of political prisoners.

It was clear that the aura of authority surrounding the guardianship of the jurist would diminish with his passing. Already, in 1988, the creation of the Expediency Council had relieved future Supreme Leaders of the burden of adjudicating disputes between parliament and the Council of Guardians. (On May 26, for example, the Expediency Council ended a long process of mediation between parliament and the Council of Guardians on a foreign investment bill, which has now become law.) A few weeks before Khomeini died, a special assembly convened at his behest removed the constitutional stipulation that the Supreme Leader had to be a theologian of the highest rank, i.e., an Object of Emulation. From now on, hundreds of lesser clerics were theoretically eligible to be the Supreme Leader, provided they had the necessary piety, courage, and “good managerial skills.” The requirement of popular recognition and approval—the pledge of allegiance, as it were—was dropped as a criterion. Having been the preserve of a revered divine whom millions believed to be an intermediary between themselves and God, the guardianship of the jurist could now be conferred on a middle-ranking theologian who had much less popular support.

The changes were designed to prepare the way for the appointment of Ali Khamenei, the president, as Khomeini’s successor. Barely two months before he died, Khomeini had dismissed Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, the well-known and much-respected cleric whom he had earlier designated as his successor. Apparently Khomeini felt that Montazeri was too independent in his thinking and too pluralistic in his outlook. Many in Qom were dismayed by Ali Khamenei’s appointment. Although he was known to be an experienced politician and to have shared many of Khomeini’s views, he was only in the upper-middle rank of clerics and had been hastily named an ayatollah. Many Iranians were troubled by the idea that a man they had elected to the mundane office of the presidency, knowing they could oust him, had become the unchallengeable vice-regent of God.

The death of Khomeini would have been a good time to trim the Supreme Leader’s powers and require that he be elected. But Khomeini’s eleventh-hour constitutional amendments pointed the other way; the revised constitution increased the Supreme Leader’s formal powers, and described his authority, with an explicitness absent from the original, as “absolute.” Furthermore, Khomeini, in some of his last statements, implied that the Supreme Leader could make any decision he considered to be in “the interests of Islam and the country.” In the eyes of some, this gave him the authority to create divine injunctions.

2.

Ayatollah Montazeri’s house in Qom is a few hundred yards from the city’s shrine, but he hasn’t visited the shrine for years. He is not allowed to see people, except his family, and cannot leave home except in an emergency. His allies talk to him on the telephone; they can also ring the front doorbell and chat with him over the intercom. Through these contacts, Montazeri keeps abreast of current theological debates as well as rulings that have been issued by other senior clerics and the political situation in Tehran. He issues his own rulings on religious matters, and replies to theological questions posed by his followers, whether through the Internet or through cassettes that are distributed by his sons. Last year, he posted a long memoir on the Internet. It was immediately denounced by the conservative establishment, and around a dozen of his supporters were arrested for helping him prepare it.

Montazeri is a ruddy-faced man with the accent of his native Najafabad. His modesty is such that, if you get into casual conversation with him, you might mistake him for an itinerant preacher. In fact, Montazeri is an Object of Emulation who is acknowledged to be brilliant, even by those who disapprove of him; as a young seminarian, he was well known for his ability to recall, word for word, lectures that he had heard weeks before. He talks bluntly, lives plainly, and equates Islam with social justice. Not for him is the political plotting for which some other clerics are known. Before his social life was restricted, he would happily share his bread and cheese with, say, a farmer who had come from Najafabad to complain about a venal official. Once the farmer had gone, Montazeri would send off an angry letter to the official’s superior.

This, at least, is the portrait drawn by his supporters. It is meant to counter the derogatory claims of some of his peers, particularly the Book of Pain, which was written by Ahmad Khomeini, the Ayatollah Khomeini’s now deceased son, after Montazeri’s dismissal by his father.5 According to Ahmad, Montazeri’s stubbornness and naiveté were his downfall. At the height of the Iran–Iraq War, he argued for reconciliation with internal enemies, and this was said to have benefited counterrevolutionary groups like the Peoples’ Mujahideen, called “the Hypocrites” by the followers of the Ayatollah Khomeini. “My intention in this letter,” wrote Ahmad, “is not—God forbid!—to suggest that you accepted the ideas and ideology of Hypocrites and Liberals.” Of course, Ahmad wanted to suggest just that.

By the standards of revolutionary Iran, Montazeri is considered a democrat. That wasn’t always the case. In the days following the revolution, he argued that Shia Islam should be named the state religion, despite Iran’s large Sunni minority. He had an important part in making the principle of the guardianship of the jurist part of the constitution—which he demanded be “far removed from every Western principle,” and he did not defend Ayatollah Shariatmadari when Khomeini humiliated him for criticizing the institution of the guardianship of the jurist. Before his dismissal, his supporters intimidated people with the slogan “Opposition to Montazeri is opposition to God.” One of them, Mehdi Hashemi, upset officials by maintaining his own connections with the Lebanese Hezbollah and the Afghan Mujahideen. In 1986, Hashemi disclosed secret efforts by Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who was running Iran’s war effort against Iraq, to buy arms from Iran’s sworn enemy, the US, through the good offices of a second enemy, Israel. Rafsanjani got his revenge, and Hashemi was executed.

For all that, one can find a strain of pluralism and compassion running through Montazeri’s career. He sent private letters to Khomeini in 1988, protesting the summary execution of thousands of imprisoned supporters of the People’s Mujahideen. His criticism of Rafsanjani for prolonging the war seems to have arisen from genuine anger at the appalling loss of life. As Khomeini’s dauphin, he tried to pierce the wall that Khomeini’s possessive entourage had erected around him. According to Gholam-Hossein Nadi, a fellow cleric and longstanding ally, “other people would go before Khomeini and flatter him.” Montazeri, on the other hand, “told the truth and passed on the complaints of the people.”

Private complaint could perhaps be tolerated, but Montazeri went public after the end of the war with Iraq, criticizing the regime’s “mismanagement” and “the denial of people’s rights.” There is, he said, “a great distance between what we have promised and what we have achieved.” He accepted his dismissal with grace, perhaps relief, but it came as a shock to people who associated him with revolutionary ideals. During the early and mid-1990s, Rafsanjani, who had succeeded Khamenei as president, carried out economic reforms apparently designed to benefit people who were already privileged. At the same time, the politically influential people around Khamenei were putting slavish emphasis on the Supreme Leader’s “absolute” authority.

In 1997, Mohammad Khatami, a cleric advocating increased democracy, was elected president by a large majority. Word got around that the Supreme Leader, who was said to have lent veiled support to Khatami’s conservative rival during the campaign, was imposing his influence on the composition of the new government. At the same time, some clerics were suggesting that Khamenei be declared an Object of Emulation. Invoking his authority as author of the 1979 constitution, Montazeri, in a speech that created a sensation, asserted that the Supreme Leader’s duty was not “to interfere in everything,” but “to oversee the country.” He attacked Iran’s “monarchical set-up.” He openly suggested that Khamenei was unqualified to be an Object of Emulation, and unqualified to be Supreme Leader as well.6

The speech confirmed Montazeri’s status as the senior theological advocate of democracy within the Islamic republic. At the same time, it ruined him politically; his private college in Qom was closed, his office ransacked, and he was put under house arrest. With one exception, Montazeri’s fellow Objects of Emulation were too timid to defend him. His enforced isolation ended hopes that he and Khatami might join forces; the elected president could hardly come out in support of the man who had been attacked and dismissed from public life by the Supreme Leader.

The cause of reform suffered as a result. Montazeri’s disgrace made it impossible for reformers in Tehran to call on him for support in their struggle with the Council of Guardians, which routinely humiliates them by disqualifying Khatami supporters from seeking office, and by vetoing all legislation that would increase democracy or protect rights. Montazeri would have made a useful ally in the continuous confrontations between Khatami’s supporters and the judges, who have jailed scores of reformists, including editors, writers, economists, and mayors, among others; virtually all of the top judges are anti-reform clerics and all of them Montazeri’s theological inferiors. If Montazeri had been free to argue with Khamenei in 2000, he might have tried to dissuade him from ordering the closing of more than a dozen reform-minded publications, and from suppressing parliamentary discussion of plans to make the press freer.

In April of this year, Ali-Reza Amini, a conservative cleric in Qom, told me dryly that some of the reformers who argue today for a referendum on limiting the Supreme Leader’s powers were, in Khomeini’s time, convinced of the Supreme Leader’s absolute authority. Amini’s comment reminded me of a nagging question that occurs to me as I observe some of Iran’s reformers. Are they driven by a desire to reduce the power of the Supreme Leader, or are they mainly concerned to limit the power of Ali Khamenei?

3.

For several weeks after Bush’s speech, Iran was overcome by an irrational fear of imminent US attack. People talked of little else. There was renewed debate about the merits of reopening relations with the US. (This has now ended, amid claims by reformers that secret contacts with US officials had been initiated by influential members of the regime, without the government’s knowledge.) In the face of the external threat, a temporary understanding was reached between reformers and conservatives. Fewer newspapers were closed. Some jailed reformers—including all but one of Montazeri’s imprisoned allies—were set free. It was said that the head of the clergy court had promised Montazeri that he would regain his freedom if only he would stop issuing controversial statements.

The immediate fear has passed. Montazeri is still under house arrest. (He may have upset conservatives with a statement that was published in newspapers on April 22, in which he implicitly dissociated himself from Khamenei’s insistence that Israel be eliminated and endorsed the coexistence of Palestinian and Israeli states.) Reform-minded newspapers are now being closed down again. Despite a constitutional clause that guarantees parliamentary immunity, a senior deputy in parliament who had been demanding more press freedom, among other reforms, has been sentenced to a six months in prison. Playing chicken with the judge, he has refused to appeal his sentence.

Bush’s shadow remains. Unease over his intentions, and the politicians’ calculations of gain that may result from provoking or mollifying him, will complicate next year’s parliamentary elections—which the Council of Guardians might easily spoil by disqualifying scores of sitting members. Uncertainty about US policy will complicate the search, already beginning, for a suitable reform candidate to replace Khatami, who must step down after his second term ends, in three years. It may lend urgency to the underlying national debate about the power of unelected clerics who have defied the expressed will of the voters.

When I was in Qom this spring, a friend there observed that it is hard to find a conservative cleric who hasn’t changed his views on the legitimacy of the guardianship of the jurist. To one degree or another they all now felt the office should change so as to reflect a society that is seeking a less paternalistic sort of government. According to Sadeq Haqiqat, a reform-minded cleric, “as democratic thoughts gain ground, it’s impossible” for the religious authorities to resist efforts to modify the principle of the guardianship of the jurist. “It must evolve.” Even conservatives like Ali-Reza Amini agree it can change. He seems exasperated, furthermore, by the obstructionism of the Council of Guardians; “its political coloring,” he says, “has weakened the guardianship of the jurist.”

Four years ago, a friend of Haqiqat’s, Mohsen Kadivar, published a book in Iran, Government of the Guardian, that opened new perspectives in the debate over theologically based power.7 Kadivar examined the ten sayings attributed to the Prophet and to the imams that are commonly presented as documentary evidence for the necessity of clerical rule. According to Kadivar, a well-regarded scholar, eight of these sayings may not be authentic. Even the two sayings he considers “authoritative” cannot, he argues, be used to justify the clerics’ assumption of political power. Rather, they confer on jurists the responsibility to “propagate, publicize, and teach Islamic rulings…. There is no authoritative evidence for the absolute guardianship of the appointed jurist.”

It said something for the openness of Iranian society that Kadivar’s book could be published. Many Iranians agree that the guardianship must change. And yet it does not. “In order to change,” Ali-Reza Amini says, “there needs to be consensus, and there is no consensus.” As much as conflicting ideas, the problem comes down to people who loathe one another; their personal hatred precludes the emergence of workable compromises. The recent war in Afghanistan provided an example of the current internal political conflict. The fall of the Taliban was openly celebrated throughout Iran. Khatami’s government cooperated with the US-led coalition, providing it with intelligence and also providing considerable help to the Northern Alliance; it is now enthusiastically trying to help in Afghanistan’s reconstruction. Its efforts, however, were undermined by a small number of hard-line conservatives who apparently helped al-Qaeda and tried to undermine Hamid Karzai’s government in Kabul.

In this poisonous atmosphere, it is hard to imagine that the reformers can persuade the conservatives voluntarily to give up power. A popular explosion remains a distant prospect; most people do not want another revolution, and the police and revolutionary guard are disciplined and loyal. Unless the reformers can muster allies in the conservative establishment, or find new ways to bring public pressure on it, Iran seems fated to an unyielding form of Islamic rule.

—May 29, 2002

This Issue

June 27, 2002

-

1

The twelve imams were all male descendants of the Prophet, through Ali, the Prophet’s nephew and son-in-law. Shias believe that the imams were entrusted the leadership of the Islamic community, and that the twelfth of them, who disappeared in 874, would later miraculously return to establish an era of divine justice and truth. ↩

-

2

Khomeini’s lectures while in exile in Najaf were transcribed by his students, and brought out in book form in 1971. A version of these lectures, entitled Velayat-e Faqih (Guardianship of the Jurist), is available in Tehran, published by the Institute for the Codification and Publication of the Works of Imam Khomeini. ↩

-

3

Reinventing Khomeini: The Struggle for Reform in Iran (University of Chicago Press, 2001). ↩

-

4

Baqer Moin, Khomeini: Life of the Ayatollah (I.B. Tauris, 1999). ↩

-

5

Ahmad Khomeini, Ranj-nameh (Book of Pain; Tehran, 1989). ↩

-

6

The text of Montazeri’s speech was published in a special issue of a magazine, Arzeshha (Values), dated February 1998, that attempted to damage Montazeri’s reputation. ↩

-

7

Mohsen Kadivar, Hukumat-e Velayi (Government of the Guardian; Nashrani, 1998). ↩