for Shirley Hazzard

Vedius Pollio’s summer dining room:

reserved for the elite, and frescoed over

in interwoven shades of grove and sky.

Imagine a single lozenge of lapis lazuli

sixty feet on a side, a sea-blue gem,

soothing, even in August, to the mind of power.

Pomegranate, quince, oleander, laurel,

stone pine, cypress, myrtle, oak and boxwood,

all thick with birds, and nowhere a human presence,

except for that low-running trompe l’oeil fence:

a natural prodigy in the Second Style,

flowering simultaneously, as nature never could.

Vedius Pollio is the son of a freedman.

He is known for his cruelty and his wealth.

This dining room is the showpiece of his villa “Sans Souci,”

and, since he’s willed it to the Emperor already,

though he has never performed any action of renown,

he has no reason to fear premature death:

his pause from care should be effectual.

Tonight Augustus himself comes to dinner.

The Tyrrhenian Sea murmurs at their feet;

the Emperor smiles appreciatively at

the sow’s vagina stuffed with figs, the dancing girl,

the Falernian pale in a crystal beaker…

but then a young slave’s hand slips; the glass shatters

on the mosaicked floor. There is a silence,

and Pollio says—Let him swim with the carnivorous eels.

Before he can be dragged away, the boy kneels

at Augustus’ feet. The Emperor, thinking of Lepidus,

of Antony, says—Whose hand has never slipped once?

But Pollio, refusing to take the cue,

repeats his own command—My Emperor

has been insulted by this clumsy slave.

To the tank with him. It’s like watching tufa,

this time, Augustus and what he will do:

soft when it’s cut, hardening in the air.

The Emperor says—Bring me all of your crystal.

And with each last globe and stem iridescently

ranged before him, he stands and pulls out

the tablecloth, and makes a mental note

to have this villa razed, its frescoes as well,

when Pollio dies, which he does in 15 B.C.

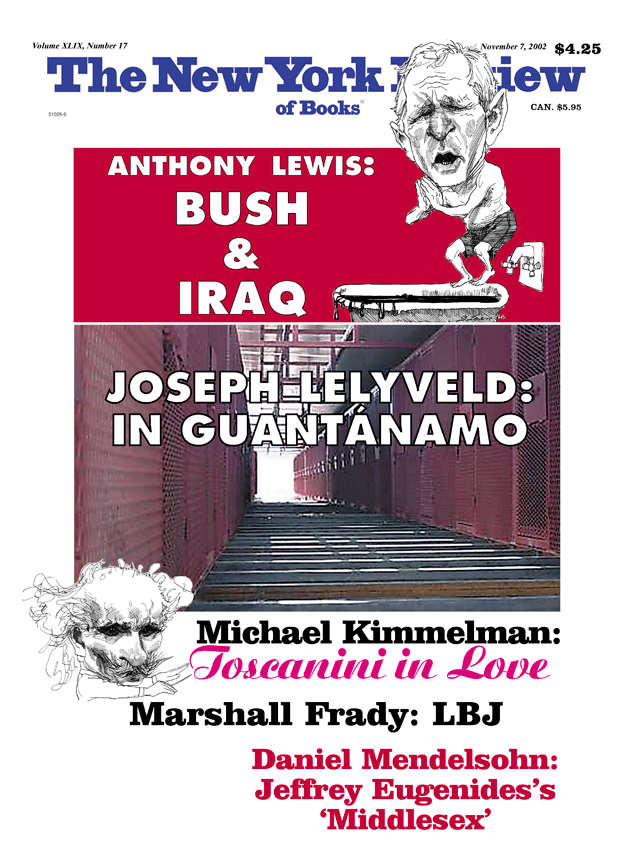

This Issue

November 7, 2002