In Washington an age of moral and philosophical sterility is deeply entrenched, and as Elizabeth Drew’s reporting in these pages attests, the result is not pretty.1 The decline dates from the end of the cold war, which suddenly and shockingly left Washington without any purpose that could be called visionary or even faintly noble.

Since then government has seemed to be mostly about raising money to get elected, and then reelected repeatedly in order to service those who put up the money. There is no moral urgency in it, no philosophical imperative at work.

Not surprisingly, accounts of Washington doings are suffused with a sense of pointlessness, a suspicion that it is an insider’s game not meant for rubes. Even the rancorous abuse that passes for political discourse feels phony—billingsgate designed to manipulate a dulled electorate. Manipulation is now such a common way of life that Washington has invented a word for it—“spinning”—and the press reports admiringly on how the press itself is “spun” by cunning “spinmeisters.”

In this atmosphere history has a dreamlike quality. A war is said to be in progress, and the President describes himself as “a war president,” but, except for military professionals, no one is asked to fight or sacrifice or even, as in World War II, to save waste fats and grease. We are asked only to shop with a generous hand, to accept a tax cut, and to be scared.

Being scared when war is in progress is no longer considered cowardly. In olden days Americans did not scare, no matter how grave the danger. Beset by truly formidable foes in the 1940s, they exulted with foolish and utterly unjustified cockiness in their certitude of victory. With Spike Jones they sang, “Heil! Heil! Right in der Führer’s face.” Unlike today’s worried patriots, they were swashbucklers. Citizens eager to become warriors.

Now fear is officially authorized. Fear manipulators issue baffling color-coded “alerts” and hair-raising speeches. As this is written, Vice President Cheney is on television in the next room raising goose bumps on an audience of Republican money donors. He praises the satanic ingenuity of the axis of evil. He hints at possible nuclear catastrophe. Death and devastation are near.

And maybe they are, but between now and then might not Washington think of some attitude more uplifting than a cringe? In Washington a president once made a devastated nation’s spirit soar by delivering a pep speech. Nothing to fear, he said, but fear itself.

Speeches that lift the spirit would sound false from the Washington operatives of whom Elizabeth Drew writes. Speechwriters still abound, but now they dream of the perfect manipulative sound bite: “read my lips,” “I feel your pain,” “axis of evil.”

The absence of any purpose more interesting than surviving another election probably explains why the men in Ms. Drew’s essays strike us as small-time connivers rather than creative thinkers, or dreamers, or even statesmen. This may be unfair; if so, they must blame the sterility of the age in which they work.

Karl Rove exemplifies the new Washington man: the almost perfect technician, a man dedicated to piloting an affable if unengaged figurehead president through the tricky shoals of governance, and doing it so artfully that reelection must result.

For this work no grasp of Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian theories of governance is needed, or ability to grapple with moral ambiguity, or any of what the first President Bush called “the vision thing.” Though Rove may be richly skilled in these departments, it would be professionally unforgivable to apply them in his work.

The chief necessities of his office are an endless supply of polls and a technical skill at interpreting them. Correctly interpreted and acted upon ruthlessly, they will lead his client to another term in the White House.

Rove is not a new political phenomenon. Bill Clinton had a Karl Rove named Dick Morris, a hired gun ready to help elect anyone ready to pay, regardless of party. As Bush trims policy to follow Rove’s course to reelected glory, so Clinton trimmed at Morris’s direction. In the process Clinton moved away from the old Democratic liberals and ended up slightly to the right of Nelson Rockefeller.

Under Rove’s political advice, Bush also seems to be taking on strange new political coloring. On first taking office he seemed bent on repealing the previous sixty-five years of American history and restoring the economics of the Harding-Coolidge-Hoover regnum. Maybe he even hoped to go back to Mark Hanna: 1896 restored to glory! An end of all taxes on capital and the moneyed classes!

He was quick enough to put Theodore Roosevelt behind him. TR had been unkind to corporations. He had tainted Hanna’s economic Darwinism with “progressivism,” chatter about the environment, and similar nonsense. Bush, to accommodate the oil, coal, timber, and mining industries, put the boot into environmentalism, granted indulgences to water and air polluters, and decided not to worry about global warming.

Advertisement

But matters have since taken a bizarre turn. Bush is now the father of history’s most gigantic budget deficit, which makes him the philosophical heir to Franklin Roosevelt. Generations of conservatives saw the devil in FDR’s red ink, and true believers still do.

So did Paul O’Neill, Bush’s first secretary of the treasury. When O’Neill fretted about it, Vice President Cheney told him Reagan had proved that deficits don’t matter, and fired him.

A lot of the deficit results from Bush’s startling decision to force creation of a multibillion-dollar Medi-care drug program, although his deep tax cuts for the wealthy had already depleted the treasury. Such programs have been despised and denounced by generations of Republicans as the work of bleeding-heart, big-spending liberalism, but political considerations seemed to be pushing Bush further and further into the New Deal way of life.

The war on terror accounts for another big part of the deficit. After the successful and popular war against Afghanistan’s Taliban government came the still baffling decision to invade Iraq and put an American army in the Middle East, if not the most dangerous area on the planet, certainly one bound to drain American wealth for years to come.

Here is another exotic political turn. In the 2000 campaign Bush opposed “nation building.” Now he proposes to protect freedom in Iraq until a new democratic nation emerges. Why we are in Iraq at all may not be clear for years to come. There was no cause to suppose that the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein was anything but hostile to al-Qaeda terrorists. Yet the Bush people immediately took the September 11 attacks as an occasion for war on Iraq.

There are various explanations. One has it that the Bush people were determined on it from their first days in office, long before September 11.2 This would suggest a political motive: Bush’s father had been criticized for not taking Baghdad and finishing Saddam in the 1991 war. If the son waded in and did the job right he might gain politi-cal points with his party’s bellicose elements.

The authors of Bush’s Middle East policy, however, seem to have been planning it throughout the Clinton years. They were a small conservative foreign policy clique based in the Pentagon, home office of the military-industrial complex.

This is now such a vast power structure that it is something of a government within the government, and like a separate government it now has its own foreign policy. Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld has often talked as if he were also secretary of state, not hesitating to insult France and Germany for refusing to join the “coalition of the willing.”

The Pentagon’s foreign policy division not only paved the road to war, but also seems to have inspired the astonishing decision to depart from tradition and commit the United States to a radical new policy of waging unilateral preventive war. The State Department is not much heard from, but it goes along quietly. Like the rest of Washington since the cold war ended so abruptly, it seems to be waiting for an idea to turn up.

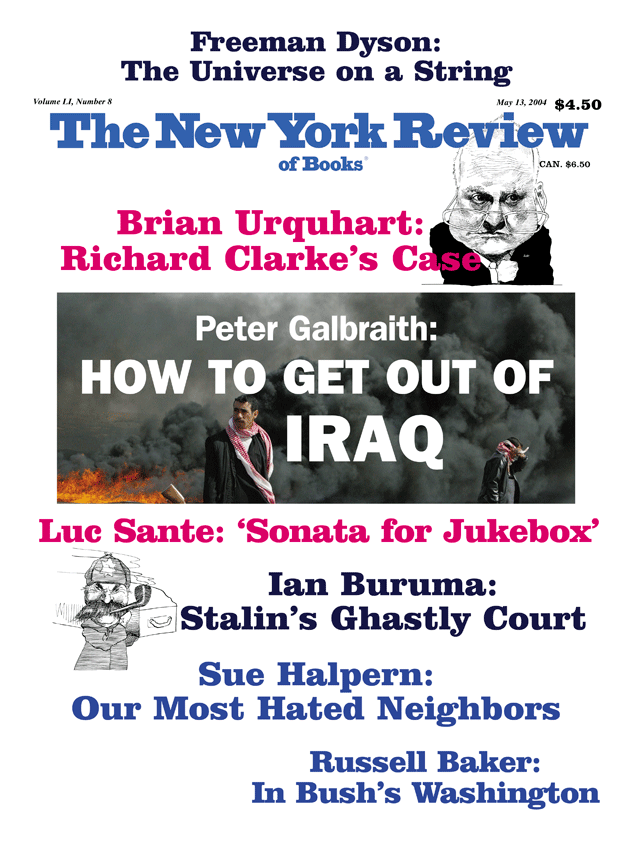

This Issue

May 13, 2004

-

1

Three of her articles, “The Enforcer,” May 1, 2003, “The Neocons in Power,” June 12, 2003, and “Hung Up in Washington,” February 12, 2004, will be published by New York Review Books this summer under the title Fear and Loathing in George Bush’s Washington. This article will appear as an introduction. ↩

-

2

Two recent books present evidence for this conclusion: Ron Suskind, The Price of Loyalty: George W. Bush, the White House, and the Education of Paul O’Neill (Simon and Schuster, 2004), and Richard Clarke, Against All Enemies: Inside America’s War on Terror (Free Press, 2004). ↩