Un incident, une bêtise,La mort de votre jument grise

—Paul Misraki, “Tout va très bien Madame la marquise”1

1.

The historical landscape is undergoing a curious change. Amid the profusion of books about the usual subjects—founding fathers, gay culture, the public sphere, memory, the Holocaust, ecology, globalization, slavery, war and peace, sex and women—a new genre has sprouted. It is scattered across so many subfields that it has hardly been noticed, but it can be found everywhere, even on the front tables of bookshops and the “required” sector of reading lists for college courses. The genre takes the form of short books on dramatic events—murders, scandals, riots, catastrophes, the kind of thing that used to be the specialty of tabloids and penny dreadfuls but now comes out in hardcovers bearing the stamp of university presses.

Despite their sensational subject matter, these books represent a serious approach to history. They deserve recognition, perhaps even an appellation contrôlée. The best name I can come up with is “incident analysis,” because for all their variety, the books share one common characteristic: they focus on an incident, relate it as a story, and then follow its repercussions through the social order and even, in some cases, across successive periods of time. They pose dizzying questions: How can we know what actually happened? What delineates fact from fiction? Where is truth to be found among competing interpretations? And they leave their readers with a Rashomon effect: the past, when seen up close, looks more inscrutable than ever.

The best-known work in this genre and the one that has served as a model for many others is The Return of Martin Guerre by Natalie Zemon Davis (1983). It takes a dramatic incident—the trial of a peasant woman accused of cohabiting with a man who had passed himself off as her long-departed husband—and peels away segments of the narrative in order to uncover aspects of gender relations and peasant life in sixteenth-century France. It also explicates successive accounts of the affair, from the original court records right up to a current movie version. Natalie Zemon Davis served as a consultant for the film and even appeared in a bit part. But after collaborating in this reenactment of the event, she warned her readers that she could not solve the riddle at the heart of it—the inside story of the Guerre ménage—and she turned her book into a reflective essay on how an incident can be known and how it is refracted over time through successive modes of communication.

Two decades later, historians are still playing with the problems of getting to the bottom of their stories. But the game is now more serious. Many of the incidents concern the blackest aspects of the twentieth century, and the scholarly difficulties are compounded by a hunger for historical knowledge that is being felt with increasing urgency throughout entire societies. While survivors sort through their memories, new generations want to know the truth about the traumas of the past.

The massacre of defenseless civilians by Japanese soldiers during their occupation of Nanking (or Nanjing as it is often put today) in December 1937 illustrates this tendency. Four recent books go back over the event in great detail, working from the assumption that if it can be understood correctly the general nature of Japanese imperialism will be revealed. The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang (1997) dramatized the massacre before a broad, English-reading public by comparing it to the Holocaust, but the crucial book that challenged the Japanese to confront their past was The Nanjing Massacre by Honda Katsuichi. Although not published in English until 1999, it provoked a great debate in Japan from the time it first appeared as a series of newspaper articles in 1971. Katsuichi, a veteran journalist from the Vietnam War, traveled to China, interviewed survivors, and reconstructed the atrocities with such precision and passion that he forced his readers to question not only the events in Nanking but also the possibility that something like collective guilt lay behind the tragedies of the war years.

Two more recent books, Nanking: Anatomy of an Atrocity by Masahiro Yamamoto (2000) and The Nanjing Massacre in History and Historiography, a collection of essays edited by Joshua Fogel (2000), show how the debate about the events has continued to reverberate through Japanese society. Yamamoto attempted to arrive at an accurate assessment of the scale of the massacre. He argued that the Japanese troops had killed about 50,000 Chinese, most of them prisoners of war or potentially dangerous soldiers disguised as civilians. That estimate discredited revisionists, who claimed that virtually no atrocities had occurred, but it fell far short of the more standard view, which set the deaths at between 100,000 and 400,000 and stressed the defenselessness of the victims. The contributors to the Fogel volume generally supported the latter interpretation, but they shifted the ground of the debate. Instead of concentrating primarily on the massacre itself, they placed the discussion of it in the context of postwar politics and showed how the historical research had intersected with changes in attitudes and memories of the war among the Japanese in general.

Advertisement

This dual concern—on the one hand with the scholarly reconstruction of an event and on the other with the history of its retelling—distinguishes the new history of incidents from the old “event history” or histoire événementielle, as it was known by its enemies in the Annales school during the 1950s and 1960s. By working in both registers, incident analysts have been able to convey the significance of defining moments in the past.

This emphasis also sets them apart from “micro-historians,” their closest relatives among professional scholars today. As developed by Giovanni Levi, Carlo Poni, Carlo Ginzburg, Edoardo Grendi, and others in Italy, micro-storia focuses on small units such as peasant villages where it is possible to study phenomena that cannot be seen at higher levels of abstraction. It deals with the constraints on the daily lives of ordinary people and the strategies that they improvised to cope with them. It aims to reconstruct social worlds systemically, even to make inferences from the micro to the macro scale of history.2

Not incident analysis. Because it concentrates on events, it seeks to understand the way people construed their experience rather than the way they fit into structures. In practice, therefore, the analysts of incidents generally study modes of communication, public opinion, and collective memory. And they find their richest material in accounts of catastrophes, the kind that appear in newspapers and court records.

For example, in Martyred Village: Commemorating the 1944 Massacre at Oradour-sur-Glane (1999), Sarah Farmer studied a military atrocity, the massacre by the Waffen-SS of 642 innocent French townspeople in Oradour-sur-Glane on June 10, 1944, and she showed how competing narratives of the event exposed fissures in memories of the German occupation. In The Collaborator: The Trial and Execution of Robert Brasillach (2000), Alice Kaplan also reopened scars left by the occupation. She recounted the trial of one of France’s most notorious collaborators, Robert Brasillach, the pro-Nazi propagandist and poet, showing how the arguments on either side corresponded to divisions within postwar France and how Brasillach’s execution by a firing squad (after General de Gaulle refused to pardon him) still echoes in different ways among French political groups, especially on the far right.

Bloody Saturday in the Soviet Union: Novocherkassk, 1962 by Samuel Baron (2001) tells the story of the massacre of strikers at Novocherkassk on June 1, 1962, and also of the attempts to stifle or exploit it, from the initial cover-up by the Communist authorities to cold war broadcasts from the West and the samizdat narratives that surfaced during glasnost. An Absolute Massacre: The New Orleans Race Riot of July 30, 1866 by James Hollandsworth (2001) pursues the theme of massacre into American history. Hollandsworth showed how a struggle to dominate municipal elections in New Orleans erupted in an orgy of violence, which left at least thirty-four dead and a hundred wounded, exposing racism as the most important ingredient in the politics of Reconstruction. An Ordinary Atrocity: Sharpeville and Its Massacre by Philip Frankel (2001) treats an equally deadly incident, the slaughter of defenseless Africans in the township of Sharpeville, South Africa, on March 21, 1960, which became the defining event in the history of apartheid. Frankel sifted through complex and contradictory testimony in order to explain how the massacre happened and how competing versions of it became entangled in the subsequent politics of South Africa.

The most important of all the retrospective anatomies of incidents was Jan Gross’s Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland (2001). By scrupulously piecing together all the surviving evidence, Gross demonstrated that the massacre of 1,600 Jews in the town of Jedwabne during the late summer of 1941 was not orchestrated by Nazis. It was executed for the most part by Poles. In a phrase that has now become famous, Gross concluded: “Half of the population of a small East European town murdered the other half.” His conclusion provoked a profound debate within Poland, for the Poles, like the Japanese, tended to see themselves as the victims of the war.

The parallel does not extend very far, because the Japanese were aggressors while the Poles suffered horribly from aggression on two fronts, the Nazi West and the Communist East. But World War II devastated Poland in ways that were more complex and damaging than anything that could be conveyed by the standard postwar view that pitted native victims against foreign oppressors. By meticulous study of one incident, Gross forced a whole country to confront the complicity of some Poles in anti-Semitic atrocities and to reassess the course of its history throughout the twentieth century.

Advertisement

Despite the variety of their subjects, these books demonstrate a common concern that runs through all analyses of incidents: the ambition to tell stories about events in such convincing detail that they will modify the general understanding of the past. Many other examples could be mentioned, not all of them about great catastrophes like massacres. Two recent books concern incidents in labor history—the Fulton Mills strike of 1914 in Atlanta, which exposed the plight of workers in the industrializing South, and the general textile strike of 1934, which challenged the program of the New Deal. Two others concern extraordinary events that tested the cohesion and fixed the memories of small communities—the collapse of a meetinghouse under construction in Wilton, New Hampshire, in September 1773 and the abduction of a trainload of orphans bound fortwo small Arizona towns in 1904. One particularly well-done study concerns a catastrophe that never happened—the poisoning of the wine served at communion in the cathedral of Zurich on September 12, 1776. Although it eventually became clear that the wine had only gone bad, the enormity of what at first had seemed to be a sacrilegious attempt at mass murder provoked a broad debate about the nature of evil at the height of the German Enlightenment.

Many histories of incidents draw their material from trials that dramatized social or political issues—the case of an African-American convicted for murdering a white woman worker in a Chicago factory in 1888; a series of trials and executions connected with the murder of Sir Thomas Overbury in 1613, which dramatized court politics before a large public in early modern England; the trial and execution of two thoroughly bourgeois forgers who played on the conspicuous consumption among the newly rich of London in the 1770s; the case of a servant who murdered her mistress, shaking the social hierarchy and Victorian values of Brandon, Manitoba, in 1899; the Beecher-Tilton trial of 1875, which exposed fault lines in the moral and emotional world of high-minded reformers in New York. Monographs on scandals and judicial affairs appear almost every month, and they represent only one current in the rising tide of incident analysis. In a survey of books reviewed in The American Historical Review during the last three years, I have identified thirty-two works that belong to the genre. A thorough investigation of historical literature in other countries probably would turn up dozens more.

This trend should not be confused with popular histories, which often fix on spectacular incidents in order to exploit their sensational appeal. It represents a fresh concern among professional historians for the immediacy of experience and for the meanings attributed to it. But incident analysis deals with such a confusing jumble of subjects that a question inevitably arises: What does it all amount to?

2.

That question may be unanswerable, but one way to take the measure of this kind of history is to see how it is handled by a master. The latest book in the genre, A Sentimental Murder: Love and Madness in the Eighteenth Century, illustrates the strengths and weaknesses of incident analysis as developed by one of the best historians in the profession, John Brewer, an Englishman trained at Cambridge who is now a professor at the California Institute of Technology.

Brewer’s earlier books demonstrated a talent for taking on major themes of English history and turning standard interpretations upside down or inside out. In Party Ideology and Popular Politics at the Accession of George III (1976), he challenged the dominant view, associated with Sir Lewis Namier, that politics in England during the 1760s was a game of ins and outs restricted to a small elite and devoid of ideological conflict. Brewer showed that members of Parliament fought fiercely over matters of principle and that their conflicts spilled over from Parliament to a middle-class and plebeian world with a robust political culture of its own. In The Sinews of Power: War, Money and the English State, 1688–1783 (1989), he disputed the common notion that Georgian England was an undergoverned society run by gentleman amateurs in the provinces and a feeble administration in London. By explaining how the government raised vast sums of money through indirect taxes and customs duties, he demonstrated that the state was a Leviathan, capable of defeating France in a series of global wars and of creating a worldwide empire. In The Pleasures of the Imagination: English Culture in the Eighteenth Century (1997), he showed how such activities as shopping and children’s games that were usually associated with the Victorian era had already begun to transform English society in the eighteenth century. He tapped earlier research on the rise of consumerism, in order to produce a grand tableau of cultural life featuring middle-class characters in a well-stocked world of goods.

A Sentimental Murder represents a radical departure from the tendency to write big books about big subjects. It is history writ small. Brewer tells the story of a murder that occurred outside the opera in Covent Garden on April 7, 1779. A recently ordained clergyman, James Hackman, shot the mistress of the Earl of Sandwich, Martha Ray, as she was about to mount into her carriage. He then tried to shoot himself but managed only to graze his forehead. Two notes in his pocket revealed that he had wanted to marry his victim and that her refusal had made him determined to commit suicide. In the subsequent trial, Hackman’s lawyer based the defense on the notion of temporary insanity. Hackman himself testified that far from intending to kill the woman he loved, he had been overcome by a “momentary frenzy.” He professed himself ready to die for his crime, however, and he went to the gallows stoically. The crime, trial, and hanging caused a good deal of ink to spill. But the incident was soon forgotten by a public concerned with the more serious business of the American war.

Why revive the story today? It makes a good tale, of course, and Brewer tells it well. He provides vivid descriptions of the three central characters: Hackman, young, dashing, the epitome of the eighteenth-century “man of feeling”; Ray, a bit old for her part (she was thirty-five and had borne Sandwich nine children) but still beautiful and blessed with an angelic singing voice; and Sandwich, the ultimate aristocrat, an aging (sixty-one) libertine and an overbearing politician, too grand as First Lord of the Admiralty to worry about his reputation among the common herd but not above base maneuvering in order to defend his hold on power.

The crime and punishment make for a lively narrative. We get just the right amount of detail: Hackman in the pit staring up at Ray in her box during a performance of Love in a Village, a sentimental tale of star-crossed lovers; the explosion of violence outside the opera house, Ray instantly dead, Hackman flailing about on the ground: “O! kill me!…for God’s sake kill me!”; the interrogation in Bow Street: more pleas for a quick death; the trial: a plea, this time, of guilt mitigated by temporary insanity; the confrontation of death on the gallows: Hackman stoic to the end, his final prayer for Ray, his handkerchief dropped as a signal to the hangman that he stood ready to be “launched into eternity.”

Having combed through all the surrounding evidence, Brewer inserts anecdotes, not too many, not too few, at the most telling moments. The beau monde at the trial includes John Wilkes, who passes a note to James Boswell congratulating him for finding a seat near the most beautiful lady. Hackman’s corpse is dissected and put on public display at Surgeon’s Hall, where a young fencing master, Henry Angelo, views it and then repairs to a nearby chophouse but finds himself unable to eat. Nothing is touched up, nothing invented. We are not made privy to Hackman’s inner thoughts or Ray’s conflicted passions. Brewer refuses to go beyond the boundaries of what can be demonstrated by documentation. He includes thirty-five pages of notes and tells the story of the murder in twenty-seven pages.

The dust-jacket summary reduces it to two sentences:

One April evening in 1779, Martha Ray, the pretty mistress of a famous aristocrat, was shot dead by a young clergyman, who then vainly tried to take his own life. Protesting eternal love for the woman he had killed, he was arrested, tried, convicted, and hanged.

Even that would be too much for a standard history of Hanoverian England. Why did Brewer devote so much artistry and so many years of study to an incident that seems as evanescent as a daily newspaper?

Part of the answer lies in the newspapers themselves. There were a great many of them in 1779: five dailies and eight triweeklies in London and about forty published in the provinces—more than exist today. To be sure, eighteenth-century newspapers did not resemble the modern variety. They had no headlines, bylines, artwork, or features familiar to today’s readers. They looked like pamphlets, except that their pages were usually divided into columns and contained a great many short notices announcing goods for sale: hence such common names as the Public Advertiser and the General Advertiser.

The ads were accompanied by news stories, but the news could hardly be distinguished from gossip, and the stories took the form of letters sent in by unnamed “correspondents.” Professional reporters did not exist. Many of the correspondents were “paragraph writers” or hacks who went around coffeehouses gathering anecdotes, which they wrote up in snippets and sold to booksellers or printers. Acting as a primitive editor, the bookseller or printer’s foreman would cobble the paragraphs together and churn out a half sheet of undigested information. Paragraphs also came in from ordinary readers, who wanted to gossip in print; from authors, who wanted to promote their books; and from politicians, who wanted to blacken opponents and cultivate patrons.

Because so many of the readers were writers and because the news gathering took place without the intervention of professionals, newspapers grew directly out of the coffeehouse culture where they were produced and consumed. Far from providing a clear window into what had actually happened, they distorted everything that passed through them. As Brewer remarks, they were

halls of mirrors in which partial views and tendentious opinions were refracted so as to appear as transparent “facts.” As we enter them, we have to remember that nothing was quite what it seemed.

That observation brings us closer to what the book is about—not what happened on April 7, 1779, but how the murder was refracted through the publications of the time. Sandwich had enough influence to make sure that the story as it appeared in the daily press would not damage his reputation, but even papers that were hostile to him did not treat the murder as an indication of scandalous behavior in high places. Although the incident lent itself perfectly to sensational details about brains being splattered on the pavement in the center of London, the press did not make much of the blood, sex, and gore. Instead, it struck a minor key and orchestrated its stories around a single leitmotif: sensibility.

Hackman appeared in the reports as a man of deep feeling and noble sentiments, tragically overcome by an ungovernable passion. Ray, the object of his love, was no courtesan but rather a victim of circumstances, a poor girl with a pure soul, despite her liaison with Sandwich. And Sandwich himself took on a sentimental glow: the loss of his true love, whom he had maintained honorably as if she were his wife, left him with a broken heart. Far from dwelling on the violence in the manner of modern tabloids, the press covered the story as if it were an episode in a current novel of sensibility.

By 1779 English readers had become accustomed to the heavy diet of sentiment served up by Richardson, Sterne, Arthur Young, Goethe, and Rousseau. It was natural enough for the coffeehouse scribblers to portray Hackman as a cousin to Goethe’s Werther or Henry Mackenzie’s Man of Feeling instead of as Macheath, the highwayman who is the hero of John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera. But the sentimental tide spilled over from the newspapers into magazines and books, where it could not be channeled so effectively by the partisans of Sandwich.

Brewer devotes three chapters to each of the main characters as they appeared in the other print media. Sandwich got dragged through the mud in books and pamphlets by reformers who made him into a symbol of aristocratic decadence and political corruption. Some of the smut came from the corner of John Wilkes, the radical libertine who had a private score to settle with Sandwich, but most of it belonged to a racy street literature about whores and bawds. It therefore veered off into the opposite direction from sensibility, and along the way it sullied the image of Martha Ray.

These ephemeral publications cast her in bad company—not the common run of fallen women surveyed in works like Nocturnal Revels, a tour of London’s brothels, but the “demi-reps” featured in more upscale publications like Town and Country Magazine. A “demi-rep” was a half-reputable consort of a wealthy man-about-town—usually a beautiful younger woman whom he had plucked from obscurity, given a veneer of polite manners, and installed in his town house as something close to a common-law wife. Town and Country Magazine ran a series of discreetly scandalous “tête-à-têtes,” illustrated with facing silhouettes, about aristocratic rakes and their kept women. Ray and Sandwich figured prominently in this and other varieties of sex literature, which Brewer surveys with wit and gusto.

Hackman, however, did not fit in-to this context. He remained a noble figure—virtuous but driven mad by love—in the books and articles that appeared after his execution. What had made him commit such a crime? This mystery kept the story alive as it evolved through later narratives, constantly changing its form and meaning. The Case and Memoirs of James Hackman (1779), a best seller that ran through ten editions, made Hackman out to be the victim rather than the villain of the tragedy. It described him as an honorable man who had lost his heart to a femme fatale. He had been deceived both by Ray and by her companion, Caterina Galli, who led him to believe that Ray had dumped him for another secret lover. He killed the woman he loved in a frenzy of passion and despair, rather like Othello.

Love and Madness, a Story Too True (1780) carried this theme further by turning it into an epistolary novel and transforming Hackman into a full-blown romantic hero. The letters were written with such fashionable soulfulness that many readers took them to be true. Both books were put out by the same publisher, George Kearsley, who read the market perfectly and used all sorts of publicity gimmicks to exploit it. Brewer expounds their publishing history as masterfully as he explicates their texts. He shows how the lives of venal journalists, Grub Street authors, cynical politicians, libertines, and scandalmongers knit together in a common culture—an English version of Balzac’s Illusions perdues.

It makes fascinating reading, but it goes on and on. Brewer pursues every variation of the story through the nineteenth century and right up to the 1950s. We get the scientific version (Hackman suffered from the deadly third stage of “erotomania”), the Wordsworthian version (a long exegesis of the poem “The Thorn”), the Victorian version (moralistic scorn for eighteenth-century decadence), the aesthetic version (the eighteenth century as an age of elegance), the feminist version (Ray, recast as a heroine, is a victim of the double standard and of the general disempowerment of women), and many others. After 280 pages of variations on the same theme, the exhausted reader reaches the conclusion, hoping to arrive at a revelation about the import of it all.

This reader must confess that he closed the book with a sense of disappointment. Brewer has no equal in evoking the street culture of London in the late eighteenth century; but when he wanders beyond it, he confirms preexisting views. The Romantic version of the murder turns out to be Romantic; the Victorian, Victorian; and so on. None of the elaborate exegeses challenges you to change your mind about anything important—not even Brewer’s final remarks, which bring us back to the problem of assessing incident analysis.

Brewer did not think of himself as contributing to a new historical genre. He might well object that no such genre exists; and that if it did, he was under no obligation to conform to its conventions. He presents his book as an “experiment,” one that will help us sort out the confusion inherent in any attempt to separate fact from fiction. Facts, he insists, cannot be quarried from archives as if they were nuggets of reality, and they cannot be combined in a narrative that will correspond perfectly to what actually happened. To write history is to tell a story and therefore to make use of many of the same rhetorical devices that go into fiction. No version of the Ray murder can be definitive. Their endless variations expose the artifice that goes into any account of an event, his own (chapter one) included.

Okay. But we have been there before. Ranke, Michelet, even Namier (whose essays are literary masterpieces) knew that they had to rely on literary techniques to convey their understanding of the past and that historical understanding involves interpretation rather than the ability to make a text fit an event without any distortion. Brewer does not provoke a philosophic reassessment about the epistemological basis of history; he illus- trates the potential of incident analysis. Without knowing he is doing it, he does it and does it well.

What does incident analysis look like when done badly? It can be sensationalist; it can be trivial; it can misconstrue events by misplaced specificity; it can ring false. Brewer cites Simon Schama’s Dead Certainties as an experiment in blending fact and fiction that he apparently meant to emulate. But Schama embroidered his narrative with material that he had invented, and he failed to insert warning signals in his text so that readers could distinguish what he had made up from what had actually happened. Brewer invented nothing and documented everything. Like his teachers in Cambridge, he is a good British empiricist.

What then distinguishes incident analysis from other types of history? Not a philosophy but its subject matter, method, and ambition. It deals with the concatenation of events rather than merely with events themselves. It attempts to find their meanings—what they meant to the people who experienced them and to those who learned about them later. It therefore concentrates on reports of incidents and the way they echoed through various modes of communication.

Now that events reported on television dominate the news, a history of how events became embedded in the different media should have some general appeal. It also can open up new access to old problems in the past. Historians often speak of recovering lost voices when they come upon a surprising incident in the archives. They don’t hear anything, of course; they simply see some fragment of a life lived long ago that ignites their imagination. F.M. Powicke, a venerable medievalist of the old school in Oxford, described this experience as a cognitive jolt:

Sometimes, as I work at a series of patent and close rolls, I have a queer sensation; the dead entries begin to be alive. It is rather like the experience of sitting down in one’s chair and finding that one has sat on the cat.3

The sat-on-the-cat effect may have provided the power that drove incident analysis to the front tables of the bookshops. Whether it remains there or disappears like other passing fashions, no one can say. But if Brewer’s book is a symptom of a larger trend, it appears that a new genre has given academic history new life and has brought it within the range of the general reading public.

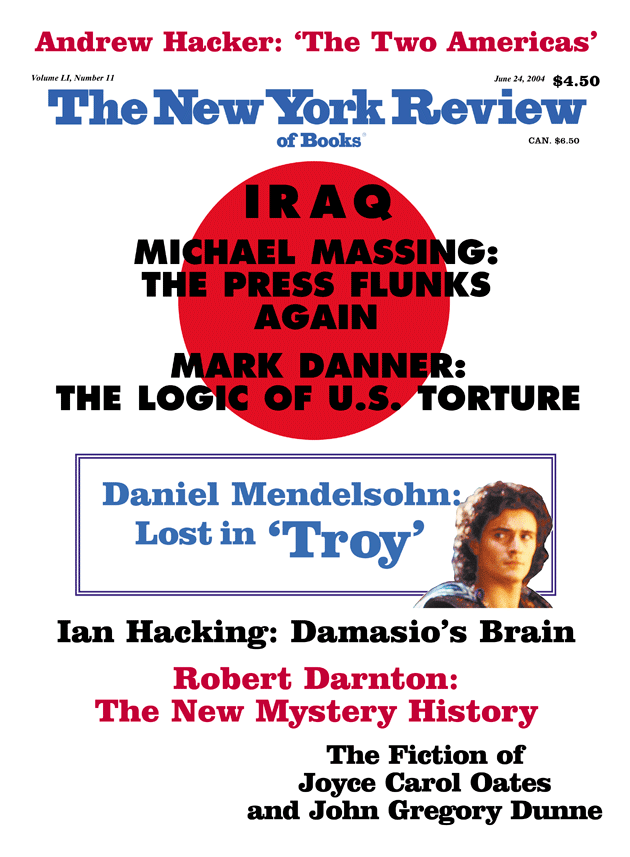

This Issue

June 24, 2004

-

1

Les grands succès de la chanson française, Vol. I 1930–1940, issued in 1935 by Disques festival, distributed by Musidisc-Europe, Paris. ↩

-

2

See Giovanni Levi, Inheriting Power: The Story of an Exorcist (University of Chicago Press, 1988) and Jeux d’échelles: La micro-analyse à l’expérience, edited by Jacques Revel (Paris: Gallimard Le Seuil, 1996). ↩

-

3

F.M. Powicke, Ways of Medieval Life and Thought (London: Odhams Press, 1950), p. 67. My thanks to Peter Brown for this reference, the one to Paul Misraki, and a great deal more. ↩