The Rare and the Beautiful is a multiple biography whose title is a quote from the reply that one of the Garman sisters—Kathleen—made to a young man who wanted to write her biography. By this time she was Lady Epstein, widow of the American-born sculptor Jacob Epstein, whose huge symbolic figures swoop around various parts of London—by the gate from Knightsbridge into Hyde Park, for instance, and over the entrance of the BBC headquarters: “It’s time you went, now,” Kathleen said to her would-be biographer.

I can’t even discuss such a ridiculous proposition. Words fail me! The mind boggles, in the famous words of the taxi driver. What muddy pitfalls one inadvertently steps into in search of the rare and the beautiful.

Kathleen was born in 1901, the third of the Garman sisters. There were seven of them, and two brothers. Kathleen and the eldest, Mary (born 1898), were the most famous in their day. They both married men who were more seriously famous—Mary’s husband was the South African poet Roy Campbell. The book is really about Mary, Kathleen, Lorna (the youngest sister, born 1911), and Douglas, the elder of the brothers. He was born in 1903, and welcomed with a flag flying outside the house, because he was the first boy in the family.

Connolly explains that the reason she chose these four was that their lives are the best documented. So this seems the moment to complain that although she provides an index, a bibliography, and a list of people she interviewed for each chapter, her book lacks a family tree. Most of the siblings had children and grandchildren, legitimate, illegitimate, and step, and there are several Kathys, Kittys, and Peggys among them; plus an extra Peggy in the shape of Peggy Guggenheim, who had an affair with Douglas Garman, and sounds much nicer in this book than she does in most others.

You can see how complicated it can get when, at the end of Chapter 10, Connolly announces that “both Lorna’s lovers had found a wife, and each bride was one of her own nieces.” The brides were Kathleen’s daughter Kitty, and Helen’s daughter Kathy by an amazingly handsome fisherman she met and married in the South of France. The bridegrooms were the poet Laurie Lee and the painter Lucian Freud, some of whose best-known and most beautiful paintings are portraits of Kitty.

The nine siblings were born in a large country house in the Midlands. All of them were exceptionally good-looking. Their father was a doctor, and very pious. He once burned a copy of Madame Bovary in front of all the children, because he found Mary and Kathleen reading it. He would have liked them to marry clergymen, “but they had other ideas. They knew he would not give his permission for them to leave home, so [in 1919] Mary and Kathleen packed their things and ran away.” To London, of course, where they both managed to get jobs connected with horses (something they knew about from their country childhood), until their father gave them an allowance which enabled them both to go to a private art school. They “soon found themselves caught up with the artistic and musical set which gathered at the Café Royal.”

Connolly lists the habitués there, past and present, and most of them seem to be writers rather than artists or musicians: Oscar Wilde, Max Beerbohm, Walter Sickert, the Sitwells, the “Bloomsberries,” i.e., Virginia Woolf, E.M. Forster, Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey, and Roger Fry. By the time the Garman girls arrived, Wyndham Lewis, D.H. Lawrence, Jacob Epstein, Nina Hamnett, Aleister Crowley, and Augustus John were also pres- ent at the scene. The restaurants and nightclubs they all frequented “were the prototypes for the kind of selective hospitality and inebriation that would later solidify into Soho legend.”

Very soon “various members of this crowd began to press their attentions upon Mary and Kathleen.” They included the composer Ferrucio Busoni, and, according to Roy Campbell, “highbrows, Jews, poets, authoresses, painters, pianists, singers, ballet dancers, and even an economist. No other contemporary women ever had so much poetry, good, bad, and indifferent, written about them, or had so many portraits and busts made of them.” Epstein made six of Kathleen. Both the sisters were not only very beautiful, but very noticeable too because they dressed romantically and unconventionally “with disheveled glamour” in long flowing skirts, and they had long, flowing hair with long bangs. In a photograph of Kathleen with her former son-in-law, Lucian Freud, during the early 1970s (when she was in her early seventies too) she still has shoulder-length black tresses, though without the bangs. The sisters’ high visibility makes their protests against attracting attention (like Kathleen’s rebuff to her would-be biographer) seem a bit phony. But there can be no doubt that they were genuinely well informed and passionate about music, art, and literature.

Advertisement

In 1921 Epstein saw Kathleen in a restaurant. He loved and studied Egyptian art, and she had a Nefertiti look about her. He asked her to sit for him. They went to bed together and next morning the sittings began. He was twenty-one years older than she, and Mrs. Epstein (Epstein’s knighthood didn’t come until 1954) didn’t mind too much about models becoming mistresses. She already had living with them his little daughter by a previous one. But Kathleen wouldn’t go away, as the earlier ones had done. So Mrs. Epstein made a rendezvous with her and shot her with a pearl-handled pistol, wounding her in the shoulder. Epstein was famous by then, so the incident was a feast for journalists. When Kathleen came out of the hospital, Mrs. Epstein made her go for a drive around the park in an open taxi, “so that all the world could see there was no enmity between them.” For more than twenty years Kathleen had to make do with being “a parallel wife” with Epstein spending regular nights with her on Wednesdays and sometimes on Saturdays. Mrs. Epstein died in 1947. In 1955 Epstein finally married Kathleen, and in 1959 he died. Connolly says that the couple’s last years were very happy ones.

But Kathleen’s life had a lot of sadness in it. Three of her four children by Epstein died young; only the second eldest, Kitty, survived. One child died at birth. Esther, the second girl, committed suicide. Theo, the eldest, was an affectionate schizophrenic whose paintings were good enough to be shown at a West End gallery. He died in a hospital after a struggle with the ambulance men who had come to collect him from his room at 272 King’s Road. This was the Chelsea house that Kathleen had taken when she began her affair with Epstein, who lived close by. Apart from her children, Kathleen’s house often sheltered other Garmans, so that Epstein would “grumble with playful exasperation that ‘the Garmans aren’t a family: they’re a tribe.'”

Only two months after Kathleen met Epstein, her sister Mary met the man she was to marry.

“I was only too glad to meet my wife, and get married within a couple of days of seeing her,” Roy Campbell wrote in Broken Record. This was a slight exaggeration, since the wedding did not actually take place for another three or four months. But within three days he had moved into the girls’ studio room.

Mary was twenty-three and he was twenty, and drank a lot of beer. Connolly says that rumors of a ménage à trois were unfounded. But after Mary’s marriage, she and Kathleen became less close; mainly, Connolly thinks, because of their husbands’ mutual antipathy. Campbell’s “much-vaunted right wingery,” she writes, “was expressed with a brazenness which was more provocative than serious.” She quotes from his memoirs:

I am no pogromite myself. One can forgive the Jews anything for the beauty of their women, which makes up for the ugliness of their men. But I fail to see how a man like Hitler makes any “mistake” in expelling a race that is intellectually subversive as far as we are concerned: that has none of our visual sense, but a wonderful, dim-sighted instinct for dissolving, softening, undermining, and vulgarising.

“No wonder,” Connolly concludes, “there was enmity between Epstein and Campbell.”

Both of them were jealous lovers and husbands. The person who gave Campbell most cause for jealousy was Vita Sackville-West, who falls into the category of “authoresses” in his list of the Garman sisters’ admirers. Virginia Woolf enjoyed her aristocratic qualities:

very splendid and voluptuous and absurd…. Also she has a heart of gold and a mind, which, if slow, works doggedly; and has its moments of lucidity.

She was “thrilled” with being the hero/heroine of Woolf’s Orlando, especially with the photographs of herself en travesti. Mary Garman was jealous of Woolf (and vice versa), and Mary was the one who got dropped. Still, it was noble of her to write to Vita that she loved Orlando, but she went on to say, “I hate the idea that you who are so hidden and secret and proud even with people you know best, should be presented so nakedly for anyone to read about.” Another example of the Garmans’ professed attachment to privacy.

In 1929 the Campbells moved to an ancient farmhouse near Martigues in the South of France, where they saw Augustus John, Aldous Huxley, Nancy Cunard with her black pianist lover Henry Crowder, the painter Tristram Hillier, and Hart Crane. By this time they had two daughters, Anna and Tess. “[Campbell] was an affectionate father, but Mary tended to alternate between extreme inattention and sudden strictness.” Her ex-sister-in-law Jeanne Hewitt (the divorced wife of her brother Douglas) came to stay together with her sister Lisa Hewitt, both of them beauties. So “the Campbells lived, briefly, in a happy ménage à quatre with the Hewitt sisters.”

Advertisement

Jeanne was not the only person to fall under the spell of one Garman after another. The Garmans’ paternal grandmother had been much admired by their great-uncle, and when she married his brother instead of him, he promptly married her aunt. Among their own generation, too, more than one lover would be passed around.

From France the Campbells moved to Spain and converted to Catholicism. In 1957 Roy died in an automobile accident. He had a drink problem, but Mary was at the wheel when a tire burst.

Lorna, the youngest of the Garman sisters, was the most dazzling of all, according to Connolly, and she was “wild.” In her photographs, she looks ravishing, but less exotic than her sisters, more of an English rose. After Dr. Garman’s death, his impoverished widow moved to a village in Herefordshire in the far west of England. Only the three youngest children were with her: Mavin, Ruth, and Lorna.

The young Garmans were certain they were different and better than those around them. In these remote surroundings, the three relied on one another for company, and they became unusually close, sharing everything and sleeping in the same room, even the same bed…. In adult life, their friends sometimes wondered whether there had been an incestuous bond among them, but Mavin maintained that there had not, although it was not scruples or taboo which stopped it, but that there were three of them, which prevented pairing.

In the index, the entries under Lorna Garman include “magnetism of,” and “as muse,” to signal her most striking qualities. (There is also a fascinating entry under “perfume used by” which tells you not only which brands Lorna—and Kathleen and Helen—preferred, but also gives a brief history of Caron, Patou, Guerlain, and Lanvin.) When she was fourteen, Lorna seduced her brother Doug- las’s much older friend Ernest Wishart in a hayrick. (“‘She was never innocent,’ as her daughter affectionately remembered.”) They married as soon as she was sixteen and she had plenty of lovers afterward. Wishart took it all in his stride. Lorna was fond of gardening (she made a beautiful one at the Wishart house in Sussex) and even fonder of horses. Toward the end of the 1940s she followed Mary into the Catholic Church. “She became very, very Catholic and gave away all her jewelry and went to mass every day and renounced all her lovers,” said one of her nieces. And she advised the mistress who succeeded her with Lucian Freud to “get a horse and become a Catholic. You’ll never regret either.” In 2000, she was the last of the Garmans to die.

Douglas Garman looks darkly handsome in his photograph, but compared to his sisters’, his life is a bit dull to read about. Since he wasn’t a sister, perhaps it would have been better to leave him out altogether. He went to Cambridge, and later became a Communist, like so many middle- and upper-middle-class intellectuals of his generation. He worked on a literary magazine, the Calendar of Modern Letters, which was edited by his friend the poet Edgell Rickword and backed financially by his brother-in-law Ernest Wishart. It folded in 1927. By then Wishart had amalgamated his publishing company with that of Martin Lawrence, the official publisher of the Communist Party, and Douglas went to work for them. He wanted to be a writer, but published only one book, a collection of poems called The Jaded Hero, a title, Connolly says, “oddly prescient of Garman’s later life.” He had an affair with Peggy Guggenheim, and a daughter by his first wife, Jeanne Hewitt. His second wife was a fellow Communist called Paddy Ayriss. It sounds as if they had a comparatively uneventful marriage, and she outlived him by thirty years after he died in 1969.

On its dust jacket The Rare and the Beautiful carries an enthusiastic recommendation from Virginia Nicholson, a third-generation descendant of Bloomsbury, being the daughter of Quentin Bell and the great-niece of Virginia Woolf. Her book Among the Bohemians, published last year, covers the period between 1900 and 1939 and some of the same ground as The Rare and the Beautiful, although of course it centers more on Bloomsbury than on the Garman connection. The two groups were quite different in spirit, but occasionally overlapped. Nicholson’s approach is more sociological and domestic than Connolly’s, and especially good on what the Bohemians cooked and ate and how dirty they were.

“With elegance and sympathy,” she writes, “Connolly weaves a deft account of the intertwined lives of her subjects, revealing their passions, their wide-ranging friendships, and their startling unconventionality.” Well, their lives were certainly intertwined and there is an unjudgmental calm about Connolly’s writing that might be called elegant. But as for sympathy, that never goes further than refraining from disapproval: there is something almost too scrupulously aloof and impartial about The Rare and the Beautiful. One never becomes fond of any of the characters, or even feels sorry for them, and there are plenty of opportunities for that.

There is one exception to this restraint: the appendix on the deaths of Kathleen’s children Theo and Esther is harrowing, especially in the case of Theo, where there was some doubt about whether a sedative given to him by his mother had brought on the collapse that led to his forcible removal to a hospital. As for Esther, her friend, the writer and anti-nuclear campaigner Wayland Young, regarded her as doomed: “In that family,” he told Connolly, “there was a chair for suicide by the hearth, long before anyone occupied it.” Connolly never seems to notice that chair (which may of course have been visible only to Young). But one can feel grateful to her for not trying to imagine any of her subjects’ feelings—for not novelizing the Garmans’ biographies at all.

This leaves her book tumultuous but a bit dry. Nicholson calls her account of the family “deft.” It was certainly brave to embark on such a complicated task, but “deft”? Connolly hasn’t made the geography of her corner of Bohemia very easy to grasp. Perhaps this is because she has chosen not to follow each sibling from the cradle to the grave, but to divide her narrative into chronological chunks: pre–World War I, the Twenties, the Thirties, and so on, a method that involves a lot of jumping to and fro between one life and another, and adds to the confusion. The subtitle promises The Art, Loves, and Lives of the Garman Sisters. But there isn’t any art; they didn’t produce any.

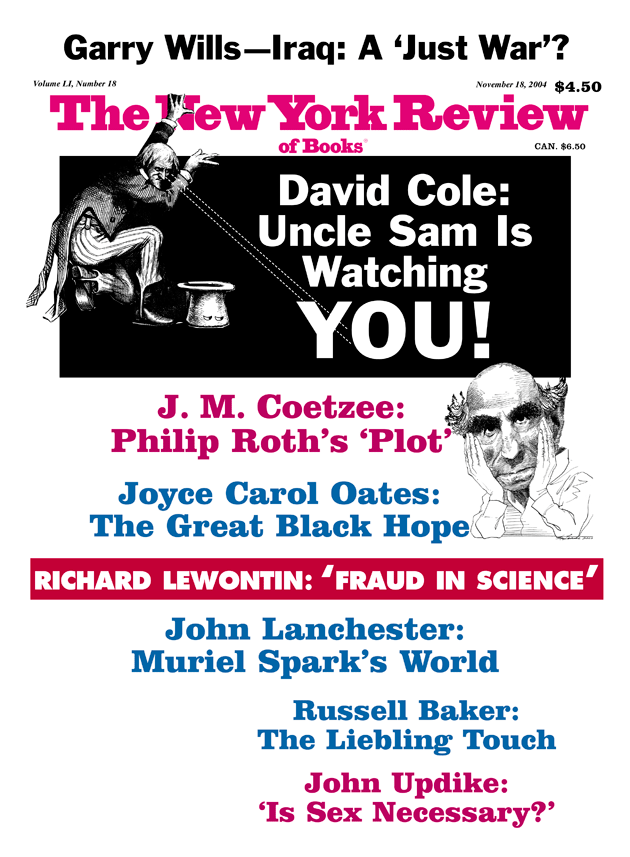

This Issue

November 18, 2004