Milan, 1991. A man wakes up after an accident yet feels he is “still suspended in a milky gray”—a grayness he seeks to evoke by quoting a dozen or so literary descriptions of fog. Finally aware that he is in a hospital bed, the man is able to answer a number of questions posed to him by a doctor in order to check whether his mind is working. He cites the Pythagorean theorem, mentions Euclid’s elements, quotes spontaneously from Moby-Dick and The Waste Land, but cannot remember his own name. The doctor explains that while retaining his “semantic memory,” everything, that is, learned in the form of publicly available factual knowledge, he has lost his private or personal memory. He doesn’t know whether he is married or not, has no recollection of his parents or of the various episodes of his life, no recall of the thousand small personal activities in which one engages every day: brushing teeth, driving a car, getting dressed.

Fortunately, the man’s legal identity is not at issue. He is Giambattista Bodoni, nicknamed Yambo. At fifty-nine he is a successful dealer in antique books, married to a psychologist, Paola, with two daughters and three grandchildren who soon come to visit him in the hospital. He observes them with equanimity but without interest and at one point, even as he caresses his grandchildren, his head fills with “a maelstrom of memories that were not mine”:

The marchioness went out at five o’clock in the middle of the journey of our life, Abraham begat Isaac and Isaac begat Jacob and Jacob begat the man of La Mancha, and that was when I saw the pendulum betwixt a smile and tear, on the branch of Lake Como where late the sweet birds sang, the snows of yesteryear softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves, messieurs les Anglais je me suis couché de bonne heure, though words cannot heal the women come and go….

This babble goes on for a full page. Yambo’s is no ordinary case of amnesia. He is, as it were, an encyclopedic mind without a self, rather as if the accident had happened to the erudite Eco himself. At once the book becomes a quest: Yambo must rediscover himself. In doing so, we presume that we will be enlightened about what exactly a self is and how it stands in relation to the collective or public mind represented by Yambo/Eco’s erudition.

In the past Eco’s novels have involved virtuoso reconstructions of historically distant worlds—the Middle Ages, the seventeenth century—with an authorial voice that hints at the fictional nature of the work; in the case of The Island of the Day Before he actually advises the reader not to take the book’s contents too seriously. The novel was thus a form of playground where a thick web of intrigue and lighthearted intellectual speculation was woven together without our being constrained to suppose that anything particularly important was at stake. Although something of that tendency remains here with the constant resort to literary quotation that necessarily invites the reader into a quiz-show complicity with the author—do you recognize this, do you recognize that?—The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana evidently proposes a more traditional form of seriousness. Yambo is oppressed by his own emptiness and indifference:

…The children were calling me Grandpa, I knew I was supposed to love them more than myself, and yet I couldn’t tell which was Giangio, which was Alessandro, which was Luca. I knew all about Alexander the Great, but nothing about Alessandro the tiny, the mine.

The quest to rediscover intimacy in a domestic setting is a problem of a different order from tracking down a murderer in a monastery or uncovering the secrets of the Knights Templar.

Yambo returns home where his affable, reassuring wife fills him in on the main facts of his life, his childhood in Turin, his parents’ deaths when he was in his late teens. They engage in further discussion about the nature of memory, this time with the help of Saint Augustine and others. Yambo compares himself to a singer stuck in the middle of a song:

I’m holding a long note, like a stuck record, and since I can’t remember the opening notes, I can’t finish the song. I wonder what it is I’m supposed to finish, and why.

Gianni, a lifelong friend, is also reassuring and affable. He tells Yambo about their school and college years, but this eventually becomes frustrating because Yambo fears that his mind is being filled by other people’s memories. To regain a sense of purpose he returns to work where he is assisted in his antique book trade by a beautiful Polish girl, suggestively named Sibila, to whom he is instantly attracted. Since his wife has already informed him with admirable equanimity that he has always been a womanizer, Yambo now wonders whether before his accident he was having an affair with the girl. If so, how should he behave, how can he find out? There is scope for comedy here, but little comes of it beyond some awkward conversation and a further collection of quotations. In the end Sibila joins the team of helpers who minister to Yambo’s alter ego, informing him this time about his daily work habits. Ominously, we discover that for years Yambo has been collecting literary descriptions of the fog. “Quotations are my only fog lights,” he jokes.

Advertisement

Some seventy pages into the novel, humming an old song about first love gives Yambo a sensation like “when someone tickles your pylorus.” He calls it “a mysterious flame.” His attentive wife observes that this song dates back to the 1940s whereas Yambo normally only sings songs from the Fifties and afterward. Clearly it is time for our hero to examine his childhood and early adolescence. End of part one.

The true nature of Eco’s interest in his novel now becomes apparent. Yambo owns a large country house outside Turin, once the property of his grandparents. During his childhood he spent the summers there. When Turin was under Allied bombardment he was evacuated there for a year and more. Unlived-in now, the house preserves intact all the encyclopedias, books, gramophone records, newspapers, comics, and magazines that the members of Yambo’s family were reading and listening to in the 1930s and 1940s. We thus have the precondition for any Eco novel, a body of texts which can be enthusiastically analyzed and a narrative alibi for paying them more attention than one would normally wish to.

Yambo leaves his family to live in this country house, in a locality called Solara, and sets about reconstructing his childhood through the comics and adventure books he had once read, not forgetting to listen constantly to old records from whatever year he is tackling, pretending to himself that they are being played on the radio that his grandfather would listen to so assiduously. His wife, his friend, and his pretty assistant have been left behind in Milan, but Yambo is looked after by the housemaid Amalia, who is old enough to be able to fill him in where necessary on his habits as a child. She is as affable as our hero’s other helpers but can be distinguished from them because she is uneducated, makes lots of grammatical errors, and apparently doesn’t know any literary quotations.

The material that Yambo/Eco wades through is fascinating. The book’s many illustrations showing old comic strips, magazine advertisements, newspaper headlines, etc. are a pleasure for the reader, likewise the inventive rhyming translations of so many Italian songs of the period, though clearly the Italian reader of the original is at an advantage here since he recognizes things he has already heard and seen. Above all we see how varied were the messages an educated young boy was exposed to under Fascism. There are religious engravings, pages from encyclopedias showing every possible variety of torture, all sorts of military uniforms. Mickey Mouse in Italian is mixed up with tales of young Fascist heroes. Meanwhile, the gramophone sings of romantic love, and then of shedding blood for the Duce.

Most interestingly, Eco shows how the names of the American cartoon figures are gradually eliminated (Buffalo Bill becomes an Italian called Tombolino) as tension between Fascist Italy and the United States grows. He is interesting too when he suggests how alien the morality of Flash Gordon, a hero determined to free people from the slavery of evil dictators, must have seemed to a child used to reading about brave Fascist children battling in the name of Mussolini. As Yambo’s researches take him into the 1940s, Eco shows us how the newspapers reported on the war, allowing Italians to read between the lines to guess at their army’s defeats, while the boys’ adventure comics remained in a state of denial; their heroes go on fighting in Ethiopia long after the country had already fallen.

If there is a problem with all this, it is that the nonfictional interest in the period material works against the fictional treatment of Yambo. “How did I experience this schizophrenic Italy?” Eco has his hero wonder about every three or four pages in an attempt to remind us that the book is supposed to be about his selfhood. “Did I love Il Duce?” Or again:

Did I have some instinctive ability to keep the realm of good, domestic feelings separate from those adventure stories that spoke to me of a cruel world modeled on the Gran Guignol?

Unfortunately, these are not questions the author can address, for Yambo simply doesn’t remember. The opportunity to consider the formation of the personality in response to the press, radio, and popular publications under Fascism is largely lost. Occasionally some old adventure book or illustration does set off “a mysterious flame” in Yambo’s mind. A child’s toy may trigger some association, or a phrase (“After looking at the frog…I spontaneously said that Angel Bear must die. Who was Angel Bear?”). But despite melodramatic references to the “desperate struggle” for memory, a mood of complacency and even self-congratulation pervades these pages as Eco delves with characteristic energy into all the old boxes of papers that keep appearing in the grandfather’s study and attic.

Advertisement

Many of the mysterious flames have to do with women. A “profile” of a woman in a French magazine is something that must have been “stamped on my heart” in childhood. It is also Sibila’s profile, Yambo decides. Ever avid to analyze the self he doesn’t have, Yambo fears he has spent his entire life seeking the same magazine-inspired love object. In general, he is haunted by anxiety that his life has been entirely foreshadowed in books. Even his nickname, he discovers, is that of a figure in a comic strip. Finally, however, he stumbles on something

that made me feel I was on the cusp of some final revelations. It had a multicolored cover and was entitled The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana. There lay the explanation for the mysterious flames that had shaken me since my reawakening, and my journey to Solara was finally acquiring a meaning.

Alas, no. This particular comic book offers nothing more than a confused story about an African queen who guards a flame that can grant immortality. Yambo is disappointed. However, by this point it is clear that rather than Yambo’s making a slow discovery, through action and interaction with other characters, of what it might mean to have a self or to be denied one, Eco has decided that his past will be discovered like a hidden treasure when some crucial clue is unearthed. Inexorably, and despite the promising opening, the story is beginning to look like Eco’s previous novels, which posit the existence of vital secrets hidden among dusty pages. No doubt when the truth comes out it will have to do with an incident in the fog and a woman who looks like Sibila and it will take place in the setting created by all that reading from the 1930s and 1940s.

A secret chapel is found in the country house. This discovery leads to the story, told in remarkable detail by Amalia, of how Yambo’s grandfather protected four partisans there. We also hear how he was forced by a Fascist to drink castor oil, and how he saved in a bottle some of the feces passed as a result of swallowing the oil and years later forced the offending Fascist to drink them. Predictably, the old chapel also offers up another generous supply of dusty boxes and papers for Yambo to analyze.

The narrator discovers his school copybooks and finds that in 1942 he wrote an entirely conventional encomium to Fascist militarism. Only nine months later, in December of the same year, he wrote a wry little essay about a boy whose mother buys an unbreakable drinking glass, symbol of modern technological achievement. When he tries to show it off to family friends by throwing it on the floor, it breaks. Immediately, Yambo deduces that some crucial change in character must have occurred between the two school essays. “I had become the narrator of a failure whose breakable objective correlative I represented.” This sounds more like the jargon of Umberto Eco the professor of semiotics at Bologna University than the words of Giambattista Bodoni the antique books dealer.

Yambo also discovers some poems written to a first love shortly after the war when he was sixteen and living in Turin again. A telephone call to Gianni reveals that the girl was called Lila Saba. “Nice name, I let it melt in my mouth like honey.” If a few moments before Yambo sounded like a literary academic, now there is nothing to distinguish him from the sentimental sops of the comics he has been reading. Gianni tells Yambo that the relationship was a “Dante and Beatrice kind of thing.” Nothing came of it, however, since Lila’s family left for Brazil, but Yambo couldn’t get over the girl and “had looked for her the rest of [his] life.” After the kind of reluctance that all witnesses must show before disclosing important evidence, Gianni finally tells Yambo that shortly before the accident that led to his loss of memory the truth had come out that Lila actually died in Brazil, aged eighteen, and hence that Yambo has spent all his life (aside from a long marriage and much womanizing) hankering after a ghost. Gianni also reveals that he has recently found out that “Lila” was short for Sibila. Yambo is distressed. He quotes a poem:

I am alone, leaning in the fog

against an avenue’s trunk…

And nothing in my heart

except your memory,

pallid and colossal…

Many readers will feel skeptical and disappointed. All those dusty pages have been turned in Grandfather’s attic to arrive at a piece of information that Gianni could cheerfully have supplied way back, namely that Yambo, who had seemed such a self-assured, sensible fellow, has spent forty years and more obsessed with an adolescent girl with whom he never exchanged more than two words. It is understandable that at this point Eco hurries the plot on with a little deus ex machina.

Shortly after his arrival at Solara, Sibila had mailed Yambo the proofs of a new catalog of the books his business is offering for sale. As a joke, she introduced into the list a 1623 First Folio of Shakespeare quoting a very low price, just to check whether Yambo was going through the proofs carefully. He nearly had a heart attack. The reader has thus been made aware of the monumental importance to a book dealer of this rare publication. Now, exactly as Eco’s novel seems to have become irretrievably trite, Yambo discovers, in yet another dusty box in the old house…a real 1623 First Folio of Shakespeare:

Now here I am, in my grandfather’s study, touching my treasure with trembling hands…. It is not Lila’s photo, but it is an invitation to return to Milan, to the present. If Shakespeare’s portrait is here, Lila’s portrait will be there. The Bard will guide me toward my Dark Lady.

So far we have been given the impression that Yambo’s femme fatale was blonde. Never mind. This kind of loose melodramatic rhetoric can be taken as an indication of the trouble Eco is in. Facetiousness comes to his aid. “This is surely the greatest stroke of my life,” Yambo announces. Overwhelmed by excitement he passes out and, reduced by his great stroke to some kind of semicomatose state… recovers his memory. End of part two.

Unfortunately, though he now repossesses his past, Yambo has no control over the order in which memories play out before his closed eyes, thus delaying various revelations for a further hundred pages and more. We can summarize as follows. In 1944 the thirteen-year-old Yambo was involved in a dramatic war adventure. He and other boys had learned how to climb the all-but-unclimbable gorge above Solara to the village of San Martino. One day eight Cossacks fleeing from the Nazis took refuge in San Martino.

The Germans had blocked the road, but there was a thick fog—the fog we have been patiently waiting for. The partisans convince young Yambo to guide them up the gorge in the night in the fog to retrieve the Cossacks. Arriving at San Martino they find the Germans have advanced up the road and they are forced to take two Germans prisoner and bring them along on the return trip down the impossibly steep slope. German dogs sniff them out. They are followed. The pursuers begin to shoot into the fog. To save the situation, Yambo’s friend, the anarchist Gragnola, takes the Germans down another path, kills them, and pushes them off the cliff. The dogs won’t be able to follow the group now and the Cossacks are saved. Yambo returns home safely but Gragnola is captured and slits his own throat to avoid giving information to the Germans. “And I was alive,” Yambo remembers. “I could not forgive myself for that.” He falls into a deep depression.

Told over fifty or so pages, this is the longest stretch of uninterrupted realistic narrative in the book, but the consequences for the boy’s psychology seem forced. Yambo has behaved admirably, even heroically, just like the boys in all his adventure comics, but rather than being proud of himself he is oppressed by guilt, irretrievably traumatized, condemned for life to collecting quotations about the fog. A religious crisis with strong echoes of Stephen Dedalus in Portrait of the Artist is followed by sublimated love for Lila, a love extensively compared with Cyrano de Bergerac’s love for Roxanne. The promise of the girl can bring him out of his depressed state, but his fear of sin prevents him from touching her.

All is now explained. Yambo with his regained memory thinks and reflects in exactly the same way as Yambo without his memory. A self is a trifle. The recovery of his past, however, has not brought with it whatever strategies he must have developed over the years to deal with his unhappy adolescent experiences. We have no sense of how he could have conducted his adult life, or indeed who he really is. No matter. All we need now is a finale. Yambo is distressed that he cannot recall Lila’s face. Wryly, comically perhaps, in whatever strange mental state he is now in, he calls on Queen Loana (she of the comic strip) to grant him this vision. He is rewarded thus:

And at last, great God, I saw like the apostle, I saw the center of my Aleph from which shone forth not the infinite world, but the jumbled notebook of my memories.

Eco now scrambles together all the boy’s literature of the previous chapters in a pseudoreligious vision which goes on for a dozen pages or so and promises to climax in a glimpse of the beloved Lila’s face:

Down come the Seven Dwarves, rhythmically reciting the names of the seven kings of Rome, all but one; and then Mickey Mouse and Minnie, arm in arm with Horace Horsecollar and Clarabelle Cow, bedecked with diadems from her treasure, to the rhythms of “Pippo Pippo doesn’t know.”

Et cetera. As the girl is about to appear we are offered this image:

I…feel on the verge of orgasm, as my brain’s corpora cavernosa swell with blood, as something gets ready to explode—or blossom.

But Yambo blacks out and, so far as we know, quite probably dies before receiving his revelation. This too—the tease of final revelation denied—is the usual way for an Eco novel to end.

What are one’s reflections on having read through the 450 pages of The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana first in Italian, then, some months later, in English? That life is short; that the translation by Geoffrey Brock is truly excellent; that when it comes to creating a sense of character no amount of glib quotation and eager textual analysis can substitute for some believable dialogue between people who are actually engaged in getting through life together; that the light comic touch of postmodern fantasy may on occasion be no more than the last resort of the inept; and finally that the extent to which celebrity may outlive performance is a marvelous and truly mysterious thing to which Eco, who is a fine essayist, might usefully turn some of his erudite attention.

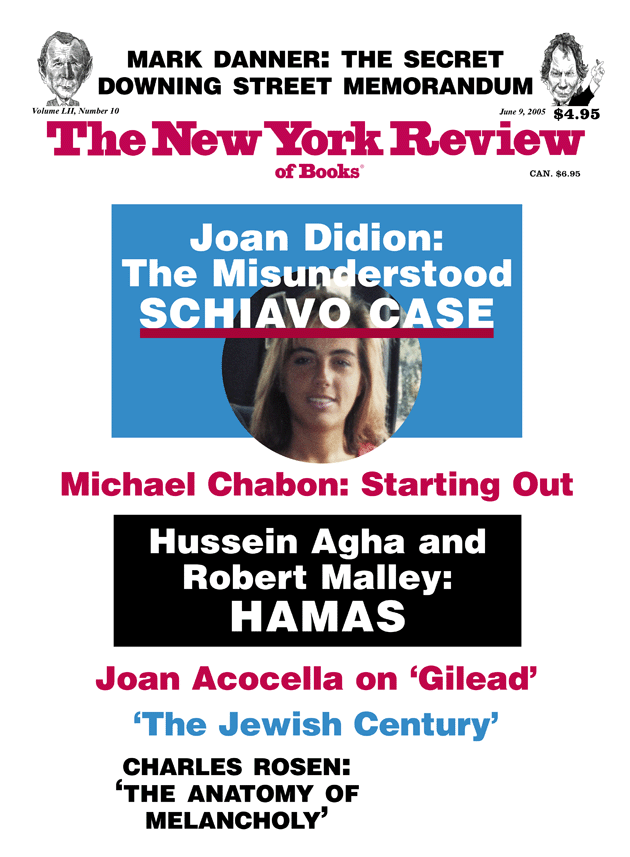

This Issue

June 9, 2005