On a tranquil autumn morning in 1654, 80,000 pounds of gunpowder exploded in the middle of Delft, destroying a third of the city. The ill-fated arsenal was located just down the street from the home of Carel Fabritius, “the greatest artist that Delft or Holland ever had.”

Decades later, in his Great Theater of Netherlands Painters and Paintresses (1718–1721), Arnold Houbraken recalled the scene:

KAREL FABRITIUS, an excellent painter of perspectives, famous as the best of his day, was also a good portrait painter. Where he was born, and when, remain unclear, but it is known that he lived for many years at Delft, and also that his name is mentioned in the municipal records for the year 1654, the 12th of October, when the powder magazine exploded, along with his mother-in-law and brother and Simon Decker, sexton of the Oude Kerk, whose portrait he was painting at the time, as well as his disciple Matthias Spoors, all of whom were very pitifully crushed to death under the rubble after the collapse of the house. Fabritius alone still had some life in him when he and the others were pulled from the rubble under which they had lain for six or seven hours, and because the physicians’ houses had mostly collapsed as well, he was taken to the hospital, where after a quarter of an hour his woeful soul departed from his horribly bruised body. And thus (he was only thirty years old), in the bright sun which was just rising, he unexpectedly succumbed. Arnold Bon wrote this elegy on the occasion of this sorrowful accident.

Thus did this Phoenix, to our loss, expire,

In the midst, and at the height of his powers,

But happily there arose out of his fire

Vermeer, who masterfully trod his path.

1.

Many artists have created famous masterpieces while still very young. Rembrandt painted his Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp when he was just twenty-six. But Rembrandt had a long and splendid career ahead of him, and when we look at the Anatomy Lesson, we think less of the painter’s youth than of his mastery. Other artists who died young—Raphael and Mozart come to mind—left such a large body of work that it is hard to imagine what they left undone. We can enjoy their work without grieving for the waste of their early deaths.

Such is not the case with Carel Fabritius. So few of Fabritius’s works have survived—twelve at last count—that when we look at his paintings we cannot help wondering about what has gone missing, and what was still to come.

Fabritius almost disappeared completely. There were other scattered references to him in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and even those were vague (“Where he was born, and when, remain unclear”). These fragments suggested that Fabritius was a link between Rembrandt, his teacher, and Vermeer, who lived close by in Delft and was ten years Fabritius’s junior. But the paintings were as scant as the biography. Some had been given fake Rembrandt signatures, others confused with the work of other masters. A few had slipped anonymously into private collections. An important group portrait went up in flames in the nineteenth century. When the British scholar Christopher Brown published a monograph on Fabritius in 1981, he could identify only eight paintings.

The recent exhibitions in The Hague and Schwerin, Germany, and their accompanying catalog offered the most comprehensive picture of Fabritius’s achievement since the seventeenth century. In his preface to the catalog Frederik J. Duparc cites the many recent scholars who have filled in holes in Fabritius’s biography. Since Brown’s 1981 study, certain paintings have been demoted from Fabritius’s oeuvre, while others, previously attributed to his contemporaries, have been added. Besides the twelve more or less secure works, Duparc’s catalog essay lists five additional paintings that are possibly by Fabritius. Even including these, we have half as many paintings by him as by Vermeer.

2.

Carel Fabritius was born in 1622 in the country known as the New World of the Dutch Republic, a land renowned for its citizens’ innovations in every field of science, religion, politics, and art. Fabritius was born in the newest part of that New World, the Beemster Polder, north of Amsterdam.

In Dutch today, the word “polder”—referring to the tracts of low-lying lands reclaimed from the sea—connotes everything dull, flat, small, and square about the Netherlands. But in the seventeenth century, the polders were glamorous new frontiers. From 1606 to 1612, the Beemster was drained in an epic struggle so heroic that the laureate Joost van den Vondel later celebrated it in ringing verses:

Cream and butter came springing from her breast.

The fishy body became untainted, virginal flesh.

When Carel Fabritius was born in the Beemster, a scant ten years after its creation, that idyll lay somewhere in the distant future. In 1622, the Beemster was still a wilderness of muddy green, unadorned by trees or towns. Fabritius’s parents had moved there six years earlier; his father was the polder’s first schoolmaster. Their fellow pioneers labored for years to bring the new land under cultivation, to build their houses, to improve the rough roads, and to dig and deepen the canals that kept the land from sinking back into the sea. The region was so new that the church was not dedicated until a year and a half after Fabritius was born. That church, in Middenbeemster, is one of the earliest purely Protestant churches in the Netherlands. It was designed by Hendrick de Keyser, who also created Holland’s supreme patriotic monument, the tomb of William of Orange in Delft.

Advertisement

In addition to running the school, Carel Fabritius’s father, Pieter Carelsz, was an amateur painter. Only one painting attributed to him survives, a large panel showing the church of Middenbeemster, which is rendered in the naive manner of the folk artist. Pieter Carelsz has filled in the space to the left of the soaring steeple with some stiff clouds, through which an angel bursts, dangling the Beemster’s matter-of-fact coat of arms: a cow in a field, atop a layer of water. For one presumably without artistic training, it is a commendable job. But it hardly foreshadows the genius of his son.

Little is known about Carel Fabritius’s youth or early training, but his father’s hobby must have influenced his sons, since three of them became painters. In 1641, aged nineteen, Carel married the sister of Middenbeemster’s minister and soon decamped to Amsterdam, where he became a pupil of Rembrandt’s. During this period, he made several pictures in the style of his teacher. Rembrandt’s influence surfaces not only in the dark palette of these early works but in the way his pupil treats traditional themes, removing overt literary and historical symbolism in order to play up the expressiveness of his figures. We know from technical research that when Fabritius’s “successor” Vermeer revised his own works, it was often to remove the elements that most obviously lent themselves to symbolic meanings. At this early stage, when he was painting works on biblical or classical themes, Fabritius, too, seems to be trying to free his work from the dense allusiveness that had sustained artists of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Fabritius’s first steps in this direction seem timid, and even occasionally baffling. One work thought to be from his period with Rembrandt is Hera (circa 1643). The subject of the painting is probably an episode from the Iliad, Hera’s flight to the house of Oceanus and Thetis during the battle of the gods and giants. The picture shows a woman reclining by a waterside, stalked, perhaps, by some off-screen pursuer. She is cowering at the edge of the water, and in her fright has dropped a comb. The painting’s most surprising element is the eerie reflection in the water, which transforms the lovely goddess into a skeletal grotesque out of Munch or Ensor.

Yet for all her apparent distress, Hera, or whoever she is, seems a bit too posh to convey real terror. With the costly jars and an elegant parasol beside her, and the peacocks on the rock behind her, she could be enjoying an afternoon at the lakeside. Besides the ghostly reflection in the water, the only indication of danger is the comb she has let fall into the water. But this detail is lost in a blur of many others, and is so small as to be scarcely noticeable. When the viewer does pick it out, the comb only enhances the improbability of the scene. Why is a woman fleeing a bat-tle between the gods and the giants combing her golden locks by the waterside?

In a painting from the Salzburg Residenzgalerie, Hagar and the Angel, a large, glowing canvas that Fabritius painted around the same time, he located the psychological center of an ancient story more successfully than he had in Hera. The painting refers to the following story:

Hagar, fearful of her mistress Sarah, has flown to the desert, having become pregnant in Sarah’s place, after which “her mistress was despised in her eyes” (Genesis 16:5). But the angel of the Lord appeared to her by a fountain on the way to Shur, and said to her, “Return to thy mistress, and submit thyself under her hands.” When Sarah finally becomes pregnant herself, she asks Abraham to banish Hagar, who is again sent into the wilderness, together with her newborn son Ishmael. This time, too, the angel appears to Hagar and saves her from dying of thirst by showing her a well of water near by (Genesis 21:19).

Though Hagar’s second flight is the one more commonly depicted—the scene of the bereft servant and her infant son—Fabritius portrays the first flight, when Hagar is pregnant. That would not be so interesting if, as one of the contributors to the catalog, Gero Seelig, claims, Fabritius had not deliberately conflated the two scenes:

Advertisement

Only the prominently displayed flask alludes to the scene usually chosen, in which an empty flask indicates that the refugees are dying of thirst. In the earlier episode depicted here…the flask no longer refers to thirst. Indeed, because the well is not depicted… the flask is even misleading.

In this sleight-of-hand, we can suspect that the young artist is chafing at canonical practice. He has not yet abandoned the literary subject entirely, however. He blurs the two scenes, but still leaves his painting anchored in a traditional text. Still, when the trick is explained—that the artist has inserted a flask into a depiction of Hagar’s first flight from Abraham and Sarah—one can’t help but see the gesture as an inside joke.

Yet by following Rembrandt’s example and focusing on his characters’ psychology, Fabritius created a fascinating painting, with or without the biblical references. Hagar and the Angel shows a woman kneeling in prayer, not yet aware of the angel looming behind her. Fabritius has stopped the angel’s hand just before it reaches the desperate woman’s head—this central gesture is eloquent and beautiful.

3.

Fabritius did not linger in Amsterdam, and his direct association with Rembrandt soon came to an end. He returned to the Beemster a little over a year after he left, his life already overshadowed by tragedy. By August of 1643, at age twenty-one, Fabritius had buried his wife and three children.

A few paintings can be dated to his return to the Beemster, where he remained until 1650. There he seems to have concentrated on portraits. This was the period of Fabritius’s great Rotterdam self-portrait, remarkable for its sensuality. The artist’s shirt is open to show his chest, and his long curly hair falls to his shoulders. But this impression of strength and sexuality is at odds with the painter’s melancholy expression. When compared to the vigor of Rembrandt’s self-portraits painted at this age, the sadness in his student’s face is striking: Rembrandt did not show himself so nakedly until he was much older. It is among the finest of all Dutch portraits.

Another work from this period, Fabritius’s portrait of the Amsterdam silk merchant Abraham de Potter (who died shortly after Fabritius completed his portrait), includes an interesting detail: a tiny faux nail sticking out from the wall behind the sitter. This is the earliest surviving hint of Fabritius’s interest in trompe l’oeil, a heightened form of illusionism that attempts to “fool the eye.” Like so much else in Fabritius’s work, the nail is ambiguous: even as the painter suggests that the space behind de Potter is a wall and not a piece of canvas, he simultaneously undermines this illusion by placing the nail inside a plainly two-dimensional inscription.

With trompe l’oeil, the artist returns to the original wonder of painting: the illusionist’s ability to conjure up three-dimensional worlds on scraps of cloth or wood. Though there is no reason in principle why trompe l’oeil could not be used for a biblical or historical subject, such paintings are rare. This may be because the device of trompe l’oeil calls so much attention to itself that the painter’s visual cunning can overshadow any moral message the painting may have. Because of its essentially secular, non-literary character, trompe l’oeil seems to have been a perfect solution to the problems Fabritius was wrestling with in Hera and in Hagar and the Angel. Instead of blurring or adapting biblical and classical subjects, a painter of trompe l’oeil could discard them entirely, concentrating exclusively on form and color. This was a step that Rembrandt never took.

At age twenty-eight, newly remarried, Fabritius began to produce visual experiments of astonishing range and virtuosity. He moved to Delft, his second wife’s hometown, and there became known as a painter of “perspectives,” elaborate scientific constructions that depended on a minute understanding of the rules of perspective.

Perspectives took several forms, and Fabritius dabbled in several of them. Because so much of his work was destroyed in the Delft explosion, we cannot reconstruct the whole range of his experiments, though he is known to have painted trompe l’oeil wall paintings, which made a room look much larger than it was. He certainly made perspective boxes, and his reputation as a master of “perspectives” suggests that he may also have created difficult devices like anamorphoses, distended blobs that only assume their correct proportions when seen from a particular viewpoint.1

Perspective boxes were a Dutch specialty: wooden boxes whose “inside walls are painted with a highly distorted representation of an interior of a house or a church, which can be viewed in its proper proportions only through a fixed peephole,” as the catalog describes them. Only one of Fa-britius’s perspectives survives, though not in its original box. Called View in Delft, it is a rectangular canvas no bigger than two postcards placed end-to-end, showing a townscape in the center of Delft. At left, a man is seated at a table. On the table are a lute and a viola da gamba. The distorted perspective and the man’s inscrutable expression give the painting an unsettling and mysterious quality. When seen as it was originally intended—attached to a semicircular wall at the back of a small triangular viewbox—the perspective is magically corrected, but the enigma of the painting’s meaning remains.

It is impossible to see View in Delft without thinking of Vermeer, Fabritius’s younger neighbor. Nowhere is the connection between the artists clearer than in this painting. The intense colors, the rendering of light and shadow, and even the arrangement of the musical instruments on a table would later be trademarks of Vermeer. But what most strongly evokes Fabritius’s successor is the question of what the seated man is doing. In Hagar and the Angel, the literary reference, while confused, is still recognizable. In Fabritius’s View in Delft, as in the paintings of Vermeer, the question of who the seated man is and what he is doing gives the work much of its fascination.

Two years after he painted View in Delft, Fabritius showed he could conjure a mysterious world without the aid of perspective tricks. The Sentry seems like a straightforward depiction of a soldier snoozing on a bench in front of a city gate, while his vigilant dog looks on. Reading this description, one may recall Alois Riegl’s remark that “in genre scenes there is always just enough activity to distract us from noticing how little is really going on.” But the opposite is true of The Sentry: its peacefulness serves to distract us from a scene heaving with activity.

Behind the arch, a couple of legs seem, as in a snapshot, to have ambled accidentally into range of the lens. The point of view is skewed, not to disclose but to conceal. The relief above the arch, which is only half visible, shows the bottom half of a monk, standing beside a pig. The pig is the attribute of Anthony Abbot, a saint often associated with hospitals whose relevance to the scene is unknown. A staircase at top right leads from nowhere to nowhere.

Indeed, the longer one looks at the picture, the fewer of its elements make sense. A sentry, for one thing, is not supposed to be asleep. Moreover, in his catalog essay, Gero Seelig points out that the large central column supports nothing, indicating that it is the remnant of some older building. But if the column was already there, why build a gateway blocked by an existing construction? The wall on the other side of the arch is built almost directly behind the gateway, far too close to allow room for a street. “The bench,” Seelig writes,

has a different spatial orientation to either side of the seated figure…. The shadows of the dog and the man seem to be cast in different directions, while the powerful column casts no shadow at all on either the wall or the archway.

Perhaps most unsettlingly, as Seelig writes, the first archway “describes neither a basket arch nor a segment of a circle; instead, the two halves appear to have different radii.” Such an arch would be dangerously unstable. Rather than a restful afternoon scene, The Sentry shows a world on the verge of collapse.

4.

Created in 1654, Fabritius’s final year, The Goldfinch is one of the most immediately recognizable of Dutch paintings. It is a small panel that shows a brown and yellow bird, roughly life-size, perched atop his feeding box. Quickly painted in a few broad strokes, it is wonderfully lifelike.

Yet to describe it as a highly accomplished picture of a bird risks damning it by faint praise. Its modest dimensions only enhance its appeal. In this it is like those actresses who, not despite but because of their slightly bulging eyes or too-large mouths, possess some off-beat glamour that leads men to brush indifferently past more conventionally attractive women. I have often observed the picture’s star quality at the Mauritshuis, the museum in The Hague where The Goldfinch has hung for more than one hundred years. Tourists on a tight schedule, who will glance vaguely at a Memling or a Rubens and appraise a famous Rembrandt with a quick flick of the eyes, will grind to a full stop before Fabritius’s bird. It is not just that the picture is skillfully painted or beautiful; that can be said of every other work in the Mauritshuis, which is one of the finest museums in the world.

It is a trompe-l’oeil work; that is, a rendering so lifelike that in certain settings—placed on a wall painted to match its plaster-colored background, for example—an unwary passerby could briefly confuse it for a real bird. But most trompe-l’oeil works, even the most technically accomplished, are intended to confuse: to make one believe that a flat canvas is an open cupboard, or that a piece of wood is porphyry or marble. Such works are playful and often brilliant, but once you get the joke, the magical first impression may dissolve.

That is not true of The Goldfinch. From a distance, it seems three-dimensional, although up close the broad, thick brushstrokes do not merely imitate the look of feathers. Fabritius’s apparent distaste for overtly precise renderings is again apparent. Unlike other Dutch painters, such as Gerrit Dou—famous for his perfectly exact reproductions of natural textures—or Gerard Ter Borch—celebrated for his renditions of satin—Fabritius suggests the bird without lapsing into literalism. The yellow streak along the bird’s wing is nothing more than a smudge, scratched through with what may be the painter’s fingernail.

And Fabritius is equally fuzzy about what exactly he “meant” by his bird. Goldfinches had a variety of symbolic meanings. Their red foreheads associated them with the Crown of Thorns. They were reputed to protect against the plague. Chained, they could refer to captive love. And they could represent the winged soul.2 Any of these meanings, or none of them, might apply to Fabritius’s Goldfinch, but nothing in the painting gives us any clue to which meaning, if any, the artist intended.

We know exactly what the painting shows—a goldfinch—but not what it means. This tension would become the hallmark of Fabritius’s neighbor, Vermeer. Like Fabritius in his earlier works, Vermeer is least convincing when he is most explicit: the Allegory of Faith in the Metropolitan, for example, crammed with symbols, is less powerful than The Girl with a Pearl Earring. Like The Goldfinch, that picture shows exactly what its title promises. The girl, like the bird, looks out at the viewer, challenging us to wonder who she was, where she came from, what she was to the artist. Because the painting contains no answers, we immediately start imagining them: it is no wonder that Vermeer’s paintings have inspired novelists from Marcel Proust to Tracy Chevalier.

The Goldfinch invites similar questions. To Théophile Thoré, the nineteenth-century art critic who once owned the painting, the little bird was “poised for two centuries on his perch, a real Simeon Stylites!” The little bird, always on the verge of takeoff but always still and flightless, could also be a poignant reminder of his young creator’s aborted career. Or we can see him simply as a creature of intense beauty. But he just might be a winged soul.

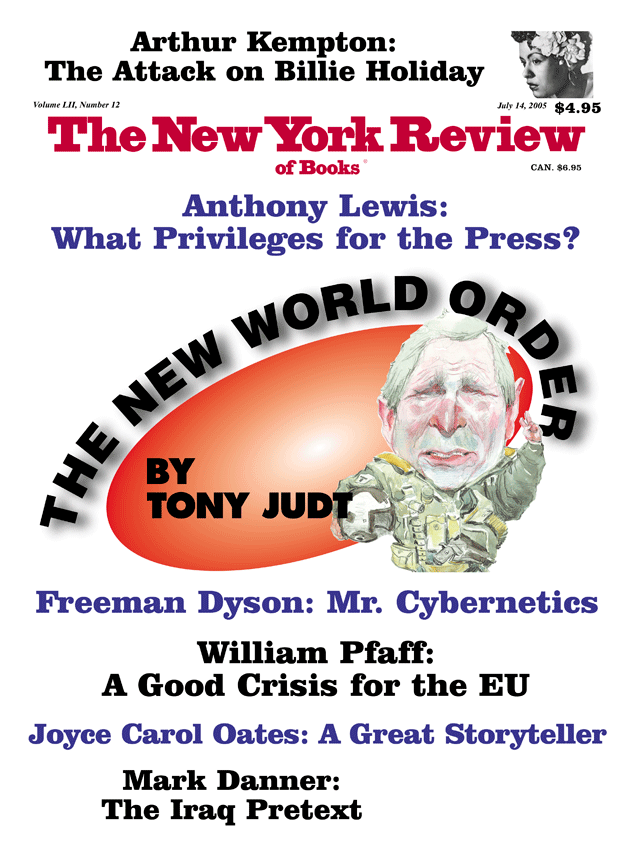

This Issue

July 14, 2005

-

1

The skull in Holbein’s Ambassadors is the most famous example of this technique. ↩

-

2

Examples of the above may be seen, respectively, in Abraham Mignon’s Still Life with Squirrel and Goldfinch in Kassel; Tiepolo’s Madonna of the Goldfinch in Washington; Gerrit Dou’s Young Woman with a Bunch of Grapes in Turin; and Paolo Veneziano’s small Madonna in Pasadena. ↩