Question: What do Shakespeare, Molière, Jane Austen, and the Brontës have in common other than genius?

Answer: They’ve all been the subject of movies that aim to show us how great writers do the thing they do—that is, write.

We’re not talking about movies that recapitulate a highly dramatic event in the writer’s life: the Dreyfus affair in The Life of Emile Zola; Oscar Wilde’s trial in a scattering of Wilde movies. Or a special case like the film of The Hours, Michael Cunningham’s highfalutin novel that glossed the life of Virginia Woolf and provided Nicole Kidman with an Oscar-winning nose. We’re talking about movies that think they can convey something about “the creative process” by dishing up conventional plots for their heroes against lots of period decor: boy meets girl, boy loses girl, we get Hamlet.

Actually, in Shakespeare in Love we get Romeo and Juliet. Joseph Fiennes is darting around Olde London hoping to scrounge up an idea for a new play, and then he encounters Viola (Gwyneth Paltrow), the young heiress who’s wildly stagestruck and far more interested in the young Bard than in the powerful aristocrat she’s duty-bound to marry. The Queen herself—Judi Dench at her most Oscar-hungry—has okayed the marriage, though she has her doubts. (No fool, she.)

Forget the cuckoo tongue-in-cheek plot, along with the doublets and the candelabra and the cleavage; forget the Will-Viola kiss-fest that quickly turns into a fuck-fest (oh, those lusty Elizabethans!); forget the dedicated-to-the-theater yet comical antics of the Players. And listen to the message on the current Shakespeare in Love DVD package: “When Will Shakespeare needs passionate inspiration to break a bad case of writer’s block, a secret romance with the beautiful Lady Viola starts the words flowing like never before!”

The key word is “inspiration,” and the message of all these lit-flicks (as well as the film bios of the more flamboyant painters and composers) is that to get the job done—to write the great play, compose the great symphony, paint the Sistine Chapel or the bridge at Arles—you need to Experience Life. Which means you need to fall in love—and then lose the loved one. And suffer. Yes, young Will Shakespeare may have done some effective work before Romeo—that’s why theater managers are hounding him to come up with something new—but it’s only when sparks start to fly between him and Lady V that the poetry perks up. Pre-Viola we see the quill faltering in his ink-stained hand, blotched and incomplete pages flung to the floor. (His more personal tool has lost its touch too.) Post-Viola, the quill flies across the foolscap—whole acts are tossed off in mere hours—though where he finds even the odd moment in which to wright his play is hard to determine, since he’s rehearsing all day and tooling all night. But that’s what inspiration will do for you.

When he actually gets going, the play he’s writing comes easily, because it just mirrors what’s going on in his life. Juliet’s nurse? Viola has one too, and her ambitious parents are Capulet clones. Mercutio killed? Will’s brilliant rival and friend, Chris Marlowe, is conveniently offed. The balcony scene? It’s a convenient balcony that grants Will access to Viola’s bed. And though unlike Romeo and Juliet the lovers don’t die, they’re cruelly torn apart—Viola, with her earl, to the Virginia colonies; Will to his commission from the Queen. A comedy next, she commands—“for Twelfth Night.” Sadder, wiser, but permanently inspired, Will picks up his quill and we see that his new heroine’s name will be…Viola! As his lost love heads for the ship that will bear her away forever, he assures her that she’ll always be his muse—though how she’ll provide the inspiration for, say, Timon of Athens or Coriolanus is not made clear.

In brief: a fantasy Shakespeare has been used as a pretext to concoct an upmarket romantic comedy and, in passing, to demonstrate how, even for the greatest of geniuses, Art imitates Life.

So much of this view of creativity is paralleled in the new movie Becoming Jane that if its costumes weren’t late-eighteenth-century rather than Elizabethan, and if the gender of the great writers involved weren’t reversed, it might not be so easy to tell the two movies apart. “Jane,” of course, is Jane Austen, and although for years she’s been scribbling away for the amusement of her family, it’s only when handsome daredevil Tom Lefroy, fresh from the fleshpots of London, turns up in the neighborhood that she finds the real-life experience that leads eventually to Pride and Prejudice. Again, the events of Jane’s romance closely anticipate the action of her novel. Tom is at first boorishly dismissive, then comes to appreciate her; Jane, once her dignity is restored, falls deeply in love. They part, yet they can’t resist each other and come together again. Unlike Mr. Darcy, however, Tom is poor and the sole support of his family back in Ireland, so finally they must go their separate ways. But Jane has now known love and suffering, and so is primed to give us Elizabeth Bennet, Marianne Dashwood, Anne Elliot, et al.

Advertisement

All that we know of the relationship between Jane Austen and the real Tom Lefroy comes from a few lines in a few of her letters. They meet during the end-of-the-year holidays of 1795, and in a letter to her sister, Cassandra, dated January 9, 1796, Jane refers to him as “a very gentleman-like, good-looking, pleasant young man, I assure you. But as to our having ever met, except at the three last balls, I cannot say much; for he is so excessively laughed at about me at Ashe, that he is ashamed of coming to Steventon, and ran away when we called on Mrs. Lefroy a few days ago.” (They had been observed dancing together more than the conventional two times.) Later in the same letter, after a good deal of light-hearted gossip, much of it about other young men (including one “whose eyes are as handsome as ever”), she goes on: “After I had written the above, we received a visit from Mr. Tom Lefroy and his cousin George.” The former “has but one fault, which time will, I trust, entirely remove—it is that his morning coat is a great deal too light. He is a very great admirer of Tom Jones, and therefore wears the same coloured clothes, I imagine, which he did when he was wounded.”

A few days later, the day before a party at the house where Tom is staying, she writes: “I rather expect to receive an offer from my friend in the course of the evening. I shall refuse him, however, unless he promises to give away his white coat.” She then instructs Cassandra to make over to a friend all her previous admirers, “even the kiss which C. Powlett wanted to give me, as I mean to confine myself in future to Mr. Tom Lefroy, for whom I don’t care sixpence.” And the following day: “At last the day is come on which I am to flirt my last with Tom Lefroy, and when you receive this it will be over. My tears flow as I write at the melancholy idea. Wm. Chute called here yesterday, I wonder what he means by being so civil….” A day or so later, Lefroy is off to his law studies in London, and that’s it, apart from a reference in a letter three years later to his being in the neighborhood, Jane being “too proud to make any enquiries.” She, as we know, never married, though there was a moment years later when she almost did. Tom went on to marry, father a large brood, and become the Lord Chief Justice of Ireland (and live to be ninety-three).

So what happened during those three or so weeks? A (very) brief flirtation? A quickly doused romance? A bruised ego? An occasion for sardonic joking? A permanently wounded heart? Since Cassandra destroyed so many letters after Jane’s death, we’ll never know. And since Austen’s anti-romantic stance is so basic to her mode of thinking and writing, we can’t tell from these few remarks whether she’s just having her usual fun or whether she’s deploying her habitual irony to mask real feelings. The tone is very much the tone of her brilliantly parodic juvenilia, and certainly in no way suggests the anguish of Marianne or the melancholy regret of Anne.

Does it matter? Do we care how strictly the plot of the movie adheres to the few known facts? Indeed, what are we hoping to find in Becoming Jane? If we’re looking for a convincing notion of what Jane Austen was really like—that is, if we’re looking to identify this “Jane” with the author of the books we love—we can take a deep breath and acknowledge that the combination of a literate script and Anne Hathaway’s committed and expert performance allows us to suspend disbelief, at least for the duration of the movie. This, despite the fact that from what we actually know, Hathaway is too good-looking, too unfettered, too modern: making little speeches about the value of fiction and the nature of irony; sliding too easily into a fuzzy feminism. Austen certainly held strong views, and no doubt asserted them with authority, but not in the spirit of a Gwyneth Paltrow or a Julia Roberts—or an Anne Hathaway. Like all of us, she was a product of, and an expression of, her own time, and we can sense the difference: this movie is the twenty-first century speaking. Even so, its surface is plausible enough, and Hathaway’s performance is persuasive enough, for us to indulge in the delusion that we’re actually encountering the famously elusive Jane Austen.

Advertisement

If, however, we’re looking to Becoming Jane for an understanding of how this particular late-eighteenth-century young lady became Jane Austen, we can only be disappointed. Jane Austen was Jane Austen from the moment her consciousness formed: the wit, the implacable powers of observation, the trenchant moral vision, the sense of the ridiculous are all evident in her adolescent writings; it didn’t take a Tom Lefroy to unleash them. Certainly the circumstances of her life informed the novels—she wasn’t a fantasist—but it’s her unique mind that animates them, and that draws us to her; that makes us want to know her (and so makes possible a film like this one). That she loved, that she suffered, may or not be true, but these things can’t begin to explain her. The movie’s title is a misnomer: you can’t become what you already are.

What Austen has become in recent years is a brand name. Thanks to the endless flow of movies and TV dramatizations, the six novels are practically household names. And they’re only the beginning. At least a dozen attempts at sequels to Pride and Prejudice are available today on Amazon. Emma has been retold from the point of view of Jane Fairfax. Jane herself is the heroine of a series of detective novels. (The ninth and latest is Jane and the Barque of Frailty: “Jane Austen arrives in London to watch over the printing of her first novel, and finds herself involved in a crime that could end more than her career.”) Not to be left out, Mr. Darcy has his own literature, as well as costarring in a “Mr. and Mrs. Darcy” crime series (Suspense and Sensibility; Pride and Prescience). This September brings us both the movie version of the recent best-seller The Jane Austen Book Club and a new book called Just Jane: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Life. There’s a Pride and Prejudice board game (“Marriage is the object”), a Jane Austen action figure….

Can any of this commerce, however sincere, help us understand the unique genius it purports to elucidate? Alas, no. “Understanding” Jane is no more a possibility than “becoming” Jane. There are the Jane Austen novels; the Jane Austen industry, including this current and perfectly respectable movie, is irrelevant.

And then there’s Molière, a new French film, in which the previously interesting Romain Duris (The Beat That My Heart Skipped) impersonates the young and very hirsute playwright, who learns a thing or two when, to escape debtors’ prison, he lends his talents to a very rich gentleman and so discovers the material for his great comedy Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme. Oh yes—he also falls madly in love with the Gentilhomme’s aristocratic Lady, from whom fate and the exigencies of the plot separate him: she must stay in her dreary marriage for the sake of her vulnerable daughter. Besides, what could the future hold for a scruffy traveling player and the elegant, and older, Mme Jourdain? He suffers, she suffers. Still, like Will and Viola, they have their fun, and plenty of it, before they must part. (Shakespeare in Love has a lot to answer for.)

It’s déjà vu all over again: boy gets girl, boy loses girl, we get Tartuffe—the name our hero assumes when in residence at the château Jourdain. Meanwhile, we’ve watched his ink-blotched hand gripping his quill as it races along, no doubt composing masterpieces inspired by Madame’s cleavage. Luckily for the young scamp, Mme Jourdain is not only muse, she’s instructress. The silly boy wants to be a tragedian, but she sets him straight: tragedy is not for him. “Make them laugh.” (Shades of Preston Sturges’s Sullivan’s Travels!)

Unlike Shakespeare in Love and Becoming Jane, Molière has no redeeming qualities. But it offers the same message they do: genius can only be explained through biographical anecdote; if you haven’t lived it, you can’t write it.

This, apparently, is also the story of the Brontës, as reconstructed in a deservedly forgotten 1946 movie called Devotion. Ida Lupino is Emily, Olivia de Havilland is Charlotte, and you may be startled to learn that they’re both in love with the same man: Paul Henreid. Emily sees him first and pines for him, but he can’t love her “that way.” It’s Charlotte who snags him in the end, though not until she’s experienced unrequited infatuation for Monsieur Heger, the proprietor of the school in Brussels where the two girls go to teach. (See Villette). So both girls suffer, which is why we have Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre. The third surviving sister, Anne, is given no love interest, which presumably is why she can do no better as a novelist than Agnes Grey and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

The horrifying story of the Brontës is known to the world, four of the five girls dying young of consumption, Emily among them. In Devotion, though, she doesn’t cough once; she doesn’t even clear her throat. She simply fades away through Henreid-deprivation, her spirit joining Heathcliff on the moors.

Even in the mid-Forties this movie was greeted with derision, although Lupino makes a game try at Emily. Its only interest today is to demonstrate that the Love + Suffering = Art equation was alive and flourishing in Hollywood sixty years ago. Its roots, of course, lie further back, in the Romantic movement of the nineteenth century—the idea of a pre-Romantic Handel or Fielding (or Shakespeare or Austen) subscribing to it is preposterous. But Hollywood has to adhere to this approach if it’s going to make this kind of movie. You can’t have a successful period piece without love and sex, so if you pin your story on a great writer, he/she has to be in love/sex. No one’s going to pay money to see Shakespeare, retired, performing civic duties back in Stratford, or Jane Austen sitting at her desk in her early forties writing Persuasion.

Some years ago Hollywood put a more contemporary writer up on the screen: Lillian Hellman. She’s not a genius like the others—far from it—and she already has her man (poor Dash), but Julia, based on Hellman’s barefaced fabrications in Pentimento, gives us several of the essential conceits of the lit-flick genre. To begin with, she too has writer’s block. There’s no ink-stained hand clutching a quill, because Lillian types, but as she’s struggling to finish her first play, The Children’s Hour, we see her tossing wads of crumpled paper to the floor. And then, to show just how blocked she is (and how cranky), she flings the bloody typewriter out the window. Luckily, Hammett is on hand to encourage her, drive her to do her best, and eventually assure her that she’s written the best play of the decade.

Most of the movie is not about Lillian the writer but about Lillian the loyal friend of the heroic Julia. (They’re Jane Fonda and Vanessa Redgrave, in case you’ve forgotten.) Along the way, however, we get a version of that obligatory rite of passage for famous writers in the movies: the scene of public triumph. It’s opening night of The Children’s Hour, and as Hellman enters the restaurant where the celebratory party is being held, the entire Broadway first-night crowd rises to its feet to acclaim her. She’s famous—just the way, as she’s confessed to Dash, she’s always wanted to be!

Flash back more than three hundred years. It’s the first performance of Romeo, and, yes, this crowd too rises to its feet. Standing ovations weren’t invented yesterday.

Jane? Years after her thwarted romance, she uncharacteristically agrees to read aloud from P and P at a public occasion—because Tom Lefroy has happened to turn up with his young daughter. Forget that Austen published anonymously and remained private about her work all her life: here’s an occasion for her to lock eyes with her lost love and to receive the sweet applause of the assembly.

Charlotte? With Jane Eyre a huge success, she’s off to London to be feted by all, and be squired around London by none other than Thackeray (Sydney Greenstreet), who tactlessly points out that Emily’s novel is greater than hers. No matter: Charlotte has the fame and the applause and the royalties, and Emily is still a nobody—and about to be a dead one.

Molière? Thirteen years have gone by since his encounter with the Jourdain household, and just as Will Shakespeare obliges Queen Bess with the comedy Twelfth Night, Molière obliges Louis XIV’s brother, Monsieur, with the comedy he’s insisted on, the Gentilhomme. Applause? Laugh till they cry? You guessed it.

So you love and you sacrifice and you suffer, but it’s all worthwhile, because sooner or later the world is at your feet. Forget genius—you’re box office. Coming next week to theaters everywhere: Ibsen in Love. Becoming Willa. Emerson.

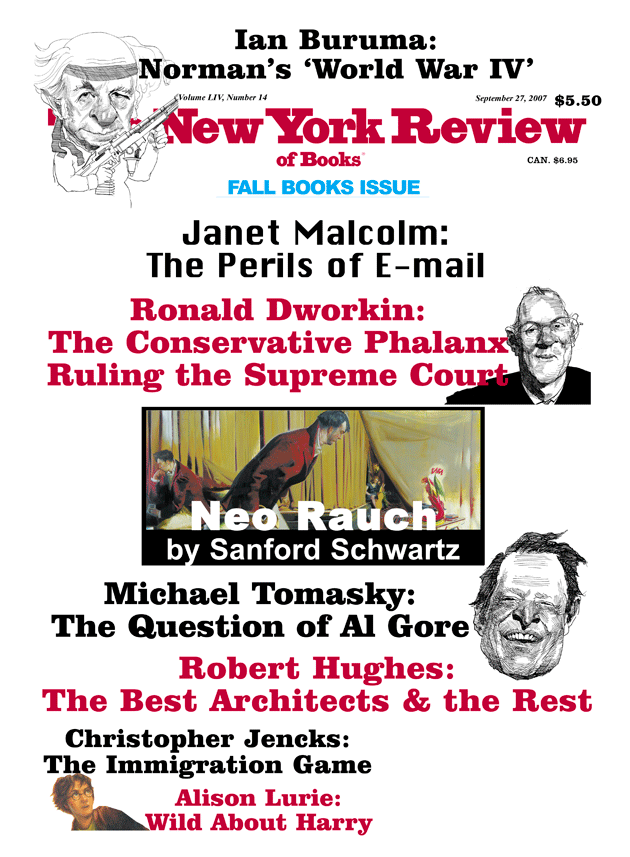

This Issue

September 27, 2007