The fundamental problem addressed by Charles Wright’s poetry is the invisibility of my inner world to you, yours to me. Unless your perceptions and responses are gathered and set down with their nuances intact, I have no way of knowing what today genuinely looks like and feels like to you. Naturalists—Kilvert, Thoreau—have kept famous diaries of their observations and reactions. But for the poet, there is an added requirement that goes beyond perceiving and responding: he must put a sheen on the day that must seem to come from inside the day itself—as though the clouds had something to express, the leaves felt an obscure desire, the sun had a purpose for its rays. Wright is not the first poet to attempt to make the natural world appear to speak and feel for itself in his lines: he acknowledges debts in this respect to Dante, Dickinson, Hopkins, Pound, Stevens.

But those writers are more explicit than he. Dante attaches an allegorical point to his similes; Dickinson makes nature an active agent in the engendering of thought, asserting that a “Slant of light” on a winter afternoon can create an “internal difference,/Where the Meanings, are”; Hopkins embraces a theology of natural fact; Pound relies on single images rather than syntactically linked ones; and Stevens never abjured the pathetic fallacy by which nature and human emotions are visibly inseparable. Charles Wright is distinguished from his predecessors by the resemblance of his poems to paintings, as has often been said.

But what, in his case, does the familiar comparison mean? Wright’s poems are painterly in their unhurried willingness to rest for some time on the plane of description, where the eye is absorbed in vision, where details are subordinated to a whole scene filling the canvas. Passion is more often implied than stated. There is, needless to say, an accumulating emotional presence to the whole, and Wright’s genius is to let his canvases do their work silently for a period of time before he allows a proposition to break in, often in order to bring closure (as a painter might break his silence to affix a verbal title to his work).

Wright names his new book Littlefoot after one of his Montana horses (Bigfoot, by contrast, is the North Wind). The horses, without reflexive consciousness, can dwell in the day as it is, and be content; and sometimes, freed from his compulsion to transform nature into verbal nature, the poet can do the same thing:

Almost noon, the meadow

Waiting for someone to change it into an other. Not me.

The horses, Monte and Littlefoot,

Like it the way it is.

And this morning, so do I.

Earth-loving in spite of a hunger for the transcendent, Wright’s poems in Littlefoot trace the darkening atmosphere of a man bidding farewell, aware that in age he sees the world less brilliantly illuminated than it was in earlier years. It is more difficult in this late phase to catch in words either the joy of perception or the joy of reminiscence. I quote, as the poet’s expression of an early ecstatic moment, lines in which the young Wright watches a fellow soldier intoning his morning prayers while standing in the Mediterranean:

His nude body waist deep in the waves,

The book a fire in his hands, his movements

Reedflow and counter flow, the chant light

From his lips, the prayer rising to heaven,

And everything brilliance, brilliance, brilliance.

—“Tattoos” #8, from Bloodlines (1974)

Although there was an elegiac note in Wright from the beginning, it now dominates (and deepens) his work, as the images drawn from nature become increasingly entropic.

Wright’s lexicon is often luxurious, as suits his impressionist scenes, but when it is fused with elegiac tones, that juncture of the indulgent and the mournful produces the paradoxical aura of sumptuous grief that rises from his pages. As his eye ranges from season to season during his seventieth year, he compiles his “night journals,/an almanac of the afterhour.” Because Littlefoot presents its thirty-five numbered poems as a single sequence, we read it as an almanac of the inner weather of an extended period; we could also call it a painter’s sketchbook. Here is part of poem #20 of Littlefoot, painting in grisaille an unforgiving wetlands landscape with fallen trees half-submerged in water. In themselves, the visual components are hardly enough for a poem: but once Wright has mediated the landscape—through an aphorism, a few metaphors, some minatory concepts, an evanescent life-cycle, a hope, and a regret—the painting-poem assumes that atmosphere of visual intensity, intellectual spareness, and colloquial interruptions by which we recognize Wright’s hand. The poet uses a palette of strictness and grayness and deadness, but at the end creates a change in hue:

Advertisement

A little knowledge of landscape whets isolation.

This is a country of water,

of water and rigid trees

That flank it and fall beneath its weight.

They lie like stricken ministers, grey and unredeemed.

The weight of water’s unbearable,

and passes no judgment.

Side by side they lie, in intricate separation.

This is a country of deep inclemency, of strict

Self-immolation and strict return.

This is the way of the absolute,

dead grass and waste

Of water, clouds where it all begins, clouds where it ends,

Candle-point upshoots on all the upstart evergreens,

Sun behind west ridge,

no moon to sickle and shine through.

The poet supplies no “I,” and for the scenery he offers nothing but spare notation and a few images: the fallen trees lie “like stricken ministers, grey and unredeemed”; the new shoots on the evergreens are candle-points. The poet’s isolation enables his noticing; it expresses itself in the “intricate separation” of the tree trunks. The “absolute,” generating the fated cycle of “strict return,” precludes change: it indicates its silent and hidden self as it creates, from clouds of origin, the grass and water that become dead grass and waste of water before they are returned to the “clouds where it ends.” This gray death—stricken and unredeemed—has no clemency; there can be no resurrection for the dead water and the dead trunks. On the other hand, this absolute passes no judgment.

Behind Wright, there always lies an absent Christianity. If he cannot have Christianity, Wright will nonetheless hold on to notions of the absolute, redemption, clemency, and judgment. Like Dickinson, he emerges from a Christian base but will not be bound by it; like her, he is too greatly attached to its conceptual vocabulary to purge himself of its diction. In a passage like the one above, the rigid trees that lie side by side, isolated in their watery chambers, are kin to Dickinson’s unredeemed “meek members of the Resurrection” who will never arise from their separate Amherst graves.

What makes Wright’s lines here (but also everywhere) so satisfying? It is the singing rhythmic pulse, of course (ascribable in part to the poet’s decision to compose only in lines with odd numbers of syllables); and it is the way the poetry imitates, in its dropped half-lines, the second wave of second thoughts. Here, the cadences of desolation appear first in the semantic heaviness of repetition: “of water,/of water and rigid trees/That flank it and fall beneath its weight…./The weight of water’s unbearable[.]” As we read, we become aware that desolation invents as well a syntax of conclusive stops, in which each period (or comma) seems irreversibly final:

…passes no judgment.

…intricate separation.

…strict return.

…the way of the absolute[.]

But even as you are being carried on by the seductive alliterative syllables and the rhythms of desolation, you are taking in the intellectual argument that Wright is making—through his stark images, semantic repetitions, and immovable stops—about the absoluteness of nature and its unredeemable and inclement cycles. At the same time, you notice a counterargument about regeneration and beauty—the candle-point evergreen “upshoots,” the setting sun. But the dead trees at the center of the painting compel the last effect to be a grieving one: after the sun sets, there will be “no moon to sickle and shine through.” (The “dead grass and waste/Of water” is a gesture in homage to Stevens and his ars poetica “The Plain Sense of Things,” which contemplates a “great pond and its waste of the lilies.”)

Wright composes narratives as well as paintings, and his impersonality is as useful to story as to impression. In his hands, the tale of Orpheus—told in twelve lines, six sentences—becomes part of a plot as grim as that of “the way of the absolute” in nature. The familiar characters appear: Orpheus the poet, Charon, the oarsman whose boat traverses the Styx, Eurydice, the beloved sought in the underworld. But the point of view has been shifted away from the lovers to Charon, the ironic observer who, though yearning that it should be so, cannot persuade himself to believe in the resurrection of the dead Eurydice. Although the lovers gain “the soot-free shore” on the far side of the Styx, they are not yet safe:

Orpheus walked, the poets say, down to the black river.

Nobody recognized him,

Of course, and the boat came,

the gondola with its singular oarsman,

And the crowd got in, a thousand souls,

So light that the boat drew no water, not even a half-inch.

On the other side, the one paved road, and they took it.

Afterward, echoes of the great song webbed in their ears,

They took the same road back to the waiting gondola,

Advertisement

The two of them,

the first to have ever returned to the soot-free shore.

The oarsman’s stroke never faltered, and he hummed the song

He had caught the faint edges of

from the distant, marble halls.

It won’t work, he thought to himself, it won’t work. And it didn’t.

One of Wright’s quietest but most intense and most characteristic effects appears in the phrase “the soot-free shore”: by our relief in perceiving, as cleansed, the earth side of the river Styx, Wright makes us shrink from the river’s implied soot-stained hell side. There is a high quotient of the unsaid that makes its silent but strong mark throughout Wright’s work. We can see within the Charles Wright of the Orpheus story a disappointed acolyte, yearning for the sacred even as he queries it. He is more than aware of his incompatible feelings, and often a tone of self-mockery (embodied here in Charon’s skepticism) gives his meditations bite.

The ecstasy of sight that Wright so defended in earlier volumes is in Littlefoot both asserted and denied. Throughout the volume, Wright fears the failure of sight: “When what you write is about what you see, what do you write about when it’s dark?” The world itself, as it presses upon him, seems to be choosing him to give verbal body to its unconscious but radiant energy; at the same time he cannot summon the radiance at will, and is increasingly forced to rely on a memory that thins as he ages. Now he can take only “cold comfort” from “Remembering how the currents of the Adige/Shattered in sunlight,/Translucent on the near side,/spun gold on the other.”

With the mention of the Adige, Wright is recalling his youthful Army posting in Verona between 1957 and 1961, after his graduation from Davidson College. He says in a 2002 interview in the Sonora Review:

After four years of arduous service in the Army of Conformity at college, I was hair-triggered for something to happen. But lucky as well, in that my arrival in Italy coincided with Pound’s repatriation, his connection with Verona…and my having bought a copy [of Pound’s Selected Poems] just before I shipped over…. And lucky beyond belief to have been assigned to a unit that had three such interesting guys as Harold Schimmel, a poet, George Schneeman, a painter, and Peter Hobart, an Art History major from Yale…. And beyond all that to have discovered poetry through reading a major contributor, a great innovator, etc. I was ready to be turned out. Just happy it turned out to be someone whose work really counted.

(It was Harold Schimmel, mentioned here, who was the soldier intoning prayer in that early moment of “brilliance, brilliance, brilliance.”) Wright went back to Italy on two Fulbrights, one to Rome, one to Padua; some of the mellifluousness of his lines perhaps derives from the presence of Italian in his ear. It is certain that the art and architecture of Italy—San Zeno, San Apollinare, the Palazzo Schifanoia—became points of aesthetic reference for him. They strengthened his conviction that a high and deep aim is necessary to art. But, as he added in the same interview:

All well and good to write about “grand” things and “grand” concepts. But you must translate them so that when you’re finished, they fit in your back pocket. So that they are iconized and objectified. So that they are apprehensible.

To create from grand things and ideas something iconic, objective, and apprehensible remains the imperative behind Wright’s poems. And for all the significance of Europe to him as a site of youthful inspiration, Wright was born in Tennessee: the American landscape, more than the Adige, has been his sustaining resource.

A first group of the American modernists (Pound, Eliot, Stevens) domesticated Europe within the American language in a way impossible to the more reverent Longfellow. In a second wave, a few of the postwar poets (such as Robert Lowell and James Wright) and some contemporary poets (notably Jorie Graham) have carried on the transatlantic barter—by residence in Europe, by translation, and by imitation of European models.

Among these poets, Charles Wright, with his Tennessee origins and Southern education, was originally the one least aligned with Europe; it is no wonder that Italy, and the cosmopolitan poetry of Pound, burst on him with the force of a revelation. Wright’s art (unlike Pound’s) precludes truculent argument and political position-taking; he reflects, he imagines, he describes, he feels, and what issues is not a polemic but a tapestry or a painting (or, in some of the poems, a story). The tapestry needle is never at rest in Wright:

Sunlight like I beams through S. Zeno’s west-facing doors,

As though one could walk there,

and up to the terraces

And gold lawns of the Queen of Heaven.

I remember the lake outside of town where the sun was going down.

I remember the figures on the doors,

and the nails that held them there.

The needle, though it has clothed many, remains naked,

The proverb goes.

So with the spirit,

Silver as is the air silver, color of sunlight.

And stitches outside the body a garment of mist,

Tensile, invisible, unmovable, unceasing.

Evocation and metaphor are here as powerful as ever; but in its revision of gold natural sunlight to silver spirit sunlight, its slide from light to mist, from the tapestry to the naked needle, the poem becomes fated to the Dickinsonian abstractions of its summary line, in which the visible disappears altogether. It is as though, like Wordsworth, Wright must concede the failing of the originally visible grace that appareled all in celestial light. The angels—in this late book—are dim, and the dead, like the gray trees, are waterlogged and destinationless:

When the rains blow, and the hurricane flies,

nobody has the right box

To fit the arisen in.

Out of the sopped earth, out of dank bones,

They seep in their watery strings

wherever the water goes.

Who knows when their wings will dry out, who knows their next knot?

Wright’s poems return again and again to Kafka’s Hunter Gracchus, who—like the Flying Dutchman, but on a bier rather than in a ship—arrives at port after port, but must leave each one when he finds no help there, must be consigned once more to his wandering bier. Christianity’s teleological consolation has metamorphosed into an endless homelessness, a fate both acknowledged and resisted by the imagination nourished on faith.

Not everything in Littlefoot is elegiac. Wright’s addresses to his reader are bracing and restorative, as he turns and asks (in the passage I quote below) what you have made of your life. Like Yeats, he thinks that each of us, poet and non-poet, must invent the unfolding choreography of his own life. The choreography that non-poets trace is a virtual poem—the same, although silent, as the spoken poem of the writer. Without that energy of individual creation, life is trivial:

We’ve all led raucous lives,

some of them inside, some of them out.

But only the poem you leave behind is what’s important.

Everyone knows this.

The voyage into the interior is all that matters,

Whatever your ride.

Sometimes I can’t sit still for all the asininities I read.

Give me the hummingbird, who has to eat sixty times

His own weight a day just to stay alive.

Now that’s a life on the edge.

To a poet, the “asininities” of the American degradation of language—by copywriters, TV anchors, pundits, politicians, educationists—are not only unbearable, but a source of anger: how is it that we don’t work harder at making our language express something individual, true, fresh, candid? Consider the hummingbird, says Wright; it is always on the qui vive. Not an unprecedented sentiment, but a vibrating Dickinsonian image, and a humorous one.

Within Wright’s work, there is a standoff between Europe and Appalachia. When Wright remembers his Appalachian past, he is always both acerbic and affectionate, as in this thumbnail obituary of the displaced Colorado truckdriver Snuffy Bruns, a figure out of the poet’s youth:

The one-legged metal-green rooster

Nailed to the wall of the old chicken house

is all that remains

Of Snuffy Bruns, at least in these parts.

A small wooden platform where Beryl, his wife (his sister

As well, it turned out), would feed Marcia,

A pine squirrel she’d almost domesticated,

who would come when called,

Rots on a spruce tree by the outhouse.

He called me Easy Money—I liked that—and made the best knives

You’re likely to come across.

Of the two, he died first, and early, much liked by all of us.

And Beryl was taken in downriver

By some family we didn’t know well.

They came from Colorado, I think.

I loved his toothless grin and his laid-back ways.

They shipped him there,

Careful truck driver to the end, after the last handshake and air-kiss,

From one big set of mountains to another, in a slow rig.

Wright’s always believable vignettes of indigenous events and persons link him to A.R. Ammons, our other great contemporary Southern poet, each of them bringing into visibility parts of America elsewhere unrecorded. I wish the textbook-makers of America would transmit our modern poetic patrimony to our children; but of course Wright’s touching portrait here would be banned on account of Snuffy’s incestuous marriage, and a good part of Ammons would be banned for “vulgar” language. It is a pity that we are as a nation still so censorious and easily frightened: we would rather have our children grow up illiterately reading mostly third-rate or innocuous poems (see any state-adopted reading text) than the real and admirable poems that our poets, Wright among them, have miraculously snatched from the air.

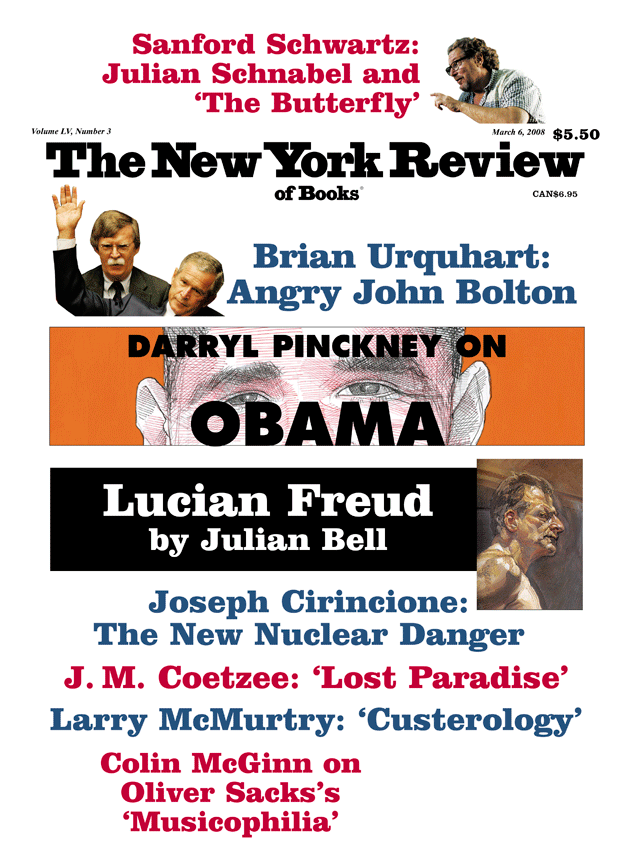

This Issue

March 6, 2008