The baby arrived early one April morning, guided into the world by a Bengali midwife while the doctor waited in the next room. It was a boy: Sophia Elizabeth and Richard Plowden’s seventh child, born, like the others, in India. The infant drew his first milk from the breast of an Indian nurse, or dai, “mine not being come,” noted Sophia in her diary—though within a few days she “did not let the Dye suckle him…. Determined to do it entirely myself.” Toward the end of June 1787, the boy was baptized William, in the first ceremony ever performed at Calcutta’s newly consecrated St. John’s Church. Friends would compliment Sophia “upon the good looks of my little William and his rosey appearance which they attributed to my Nursing him.”1

Married to a well-connected East India Company civil servant, Sophia Plowden lived in the thick of Anglo-Indian society. Her diary, kept between 1787 and 1789, helps us visualize that early colonial world. But what makes her diary especially valuable is the insight it gives into the intimacies of family life in colonial India. Few if any surviving journals of the period describe wet-nursing and infant care. Nor do contemporary travel accounts describe what it was like to travel with children in India, as the Plowdens did when they went to Lucknow in the fall of 1787.

Leaving two of the children in Calcutta with friends, the Plowdens brought with them their son Chicheley and baby William—and “a Dye in case I should find any difficulty in nursing my little Boy”—who became instant favorites with members of Lucknow’s cosmopolitan high society. The portraitist Johan Zoffany was so smitten with the Plowden boys that he “declared he would like to paint them both without any regard he was so taken with them.” At one dinner, Plowden recorded, the Nawab of Awadh himself “ask’d me a great many questions about my little ones and said William could not be flesh and blood, he was certainly form’d of Wax and Cotton.”

As a mother in India, Sophia Plowden had to confront the constant threats of disease and accident: familiar childhood hazards, such as measles and smallpox (against which the children were inoculated), and more unfamiliar dangers. She narrowly escaped being bitten by a viper coiled in her sewing drawer. There were also perennial anxieties about money, specifically whether the family had saved enough to return to Britain, and if so, in what style. And there was the urgent question of which would be best for the children: “home” in painfully distant Britain, or with her in India, with its perceived risks of contamination by climate, culture, and people—perhaps a factor in Sophia’s determination to breast-feed her child herself. Already by 1787 the Plowdens had sent their three eldest children back to Britain, to be raised by Sophia’s parents. Sophia expressed her worries and priorities when writing to her mother:

Beg’d her to be an Economist [i.e., to be economical]…. Advised her living with friends and at Yarmouth to take what was wanting for the litle ones from my stores…. To buy nothing for House. To send the Children to the best school in England.

Though Plowden’s diary is rare for its time, many of her concerns would be shared by Anglo-Indian women in generations to come—including probably her own descendants. Four of the Plowdens’ five sons, baby William included, would have careers in the East India Company civil service; before 1900 no fewer than forty male members of the Plowden family worked in India, and a third of Plowden women married Anglo-Indian officers or civil servants.2 This made them one of the largest of many imperial clans who made the East a career—and whose experiences in the later Raj have been superbly documented in Elizabeth Buettner’s monograph Empire Families.3

It would not be far wrong to say that women like Sophia Plowden helped establish the British Indian empire every bit as much as the men of sword and pen. Nor, as feminist scholars have rightly emphasized, was women’s influence in empire confined to the family sphere. European women went to India as missionaries and doctors, travelers and writers, and as political activists for and against imperial rule. Yet for all their variety and longevity, the experiences of British women in India have been more often stereotyped than explored.

The India hands said “two monsoons was the life of a man” in India—just a year flanked by two rainy seasons—but they might as well have been talking about a woman’s, as a walk through one of India’s moss-caked colonial cemeteries poignantly reveals. “Long, long before her hour/Death called her tender soul,” reads the Calcutta epitaph of twenty-year-old Rose Aylmer, whose early death inspired a pathetic verse from her lover Walter Savage Landor.4 Another, to a young mother and her baby, rhymes tragically:

Advertisement

Just fifteen years she was a maid

And scarce eleven months a wife

Four days and nights in labour laid

Brought forth and then gave up her life.

Richard Plowden’s own sister Harriet, married to a member of the Bengal Council, died after just seven months in Calcutta.5

Empire is often portrayed as a heartily masculine enterprise—of pith helmets and swagger sticks—but as these tombstones sadly attest, European women were always among its helpmeets and its victims. Often, these women play supporting parts in studies of their better-documented and officially employed menfolk. At worst, they are overtly caricatured, in novels like A Passage to India, as “braying, hardboiled, thick-skinned harridans.” A tired misogynist trope even blames the advent of the memsahibs (a term, referring to foreign white women of high social status, especially officials’ wives, that continues to have pejorative connotations) for the emergence of Anglo-Indian racist intolerance.

One of the first books to challenge such stereotypes has just been reissued. Originally published in 1988, Margaret MacMillan’s Women of the Raj appears again in a transformed scholarly environment. As MacMillan notes in a new preface, when she began her research, women’s history was relatively young, and imperial history relatively unfashionable. Today, an entire subfield has emerged devoted to the study of gender and empire. In its theoretical preoccupations and subjects, this rich, active scholarship ranges well beyond MacMillan’s narrative survey of British women’s lives in India. But Women of the Raj still presents a sympathetic, readable overview of the much-maligned memsahibs and their world.

As had already been the case in Sophia Plowden’s time, most nineteenth-century women traveled to India either with a man or to find one, as part of the “fishing fleet” hoping to hook a husband in Anglo-India’s disproportionately male society. The long voyage out provided a memorable introduction to memsahibdom, with its shipboard protocols, its hierarchies (the term “posh” derives from the old India hand’s wisdom to journey “port out, starboard home,” in order to avoid a hot southern exposure), and, above all, its claustrophobically self-contained community. As MacMillan points out, no more than 165,000 Europeans actually lived among India’s 300 million natives, even at the empire’s height. This meant that even in urban centers, the British community remained small and close-knit; while outside those centers, British women frequently experienced awful isolation. MacMillan’s attention to the tedium and pressures of imperial service makes this book an excellent counterpart to David Gilmour’s recent study of the male members of the Indian Civil Service, The Ruling Caste.6

For many, a memsahib’s life could be lonely, exasperating, and dull, with few peers for company and complex cultural codes to negotiate. MacMillan describes the peculiar challenges of Anglo-Indian housekeeping—down to gruesome details of “socks used for straining soup and fish patties shaped in the cook’s armpits.” She also captures the gloomy predicament of Victorian mothers who—like Sophia Plowden before them—had to choose between sending their small children away to school in Britain or exposing them to India’s hazardous illnesses. It was perhaps no wonder that, in an age of contraceptive ignorance, Anglo-Indian women often attempted rudimentary abortions, whether with home remedies such as doses of “hot gin and quinine” or through discreet visits to Indian practitioners in the bazaars.

There were healthier diversions. India seems to have confronted most British women with just as much sensory overload as many tourists experience there today. Judging by the diaries and letters of sharp-eyed women travelers like Fanny Parkes and Emily Eden, they could love it, hate it, or more often both. Some took up hunting, like “the Jungli Memsahib” Monica Campbell-Martin, who shot bears, crocodiles, leopards, king cobras, and the obligatory tiger. Women played cricket against male teams, who substituted brooms for bats. And then there were the hill stations, where women went to escape the summer heat, trailed by columns of coolies and camels bearing everything from ice buckets to pianos. With lending libraries, cafés, musical performances, and amateur theatrics, the stations offered an illusion of home—as well as a real social life and, for some, a whiff or more of romance. One hill-station hotel manager was said to ring a bell early each morning as a signal for people to return to their own bedrooms.

MacMillan’s chronicle of a memsahib’s career loosely parallels the rise and fall of British India itself. Plenty of British women, like men, bitterly opposed liberalization and Indian nationalism. But MacMillan wisely ends, too, by describing some of the “unconventional women” who were drawn to India for a combination of religious and political reasons. These included Madeleine Slade, who adopted a sari and the name Mirabehn, and became a passionate acolyte of Gandhi; and Margaret Noble, aka Sister Nivedita, who found a calling in the faith of Swami Vivekananda, and went on to champion Hinduism and anti-imperial resistance. The memsahibs’ world would vanish after India’s independence in 1947, but these women were perhaps unwitting forebears of a Western spiritual engagement with India that continues still.

Advertisement

The republication of Women of the Raj testifies in part to the increased prominence of its author, best known for her prize-winning Paris 1919.7 But it also attests to a greatly increased American interest in its subject matter. Even ten years ago it was common to find otherwise cosmopolitan Americans who chiefly associated India with poverty and dauntingly hot food. Now India has the bomb, embraces foreign investment, and has a place in American consciousness. Most of us have spoken to call-center staffers in some subcontinental outsourcing boomtown. Attraction to Indian spiritualism, hippie-style, has given way to the spectacle of women walking American city streets with furled yoga mats under their arms. Much has changed, in scholarship and in the world. For an audience newly interested in India and its imperial past, MacMillan’s incisive, engaging volume presents an excellent point of entry.

And yet, what about the tens of millions of Indian women among whom the British lived?

The same year that Women of the Raj first appeared, Gayatri Spivak published her influential essay “Can the Subaltern Speak?,” which has become a standard text in studies of gender and empire, the term “subaltern” used to refer to the subordinate position in which practically all Indians found themselves. Spivak suggested that British justification for empire in India could be summed up in the phrase “white men are saving brown women from brown men”—a principle made manifest by the abolition of sati, the live cremation of widows, in 1829.

Seen in one light, the abolition of sati looks like a model for more recent crusades in the name of humanitarianism and gender equality, such as the “liberation” of Afghan women after the Taliban’s fall, or campaigns against female circumcision. In its own times, however, the abolition of sati—welcomed though it was by a small, vocal constituency of Indian reformers, and, one presumes, by larger if silent ranks of Indian women—formed part of a series of cultural and legislative shifts that self-consciously imposed British “civilization” on Indians. Gestures like this, or the substitution, a few years later, of English for Persian as the East India Company’s administrative language, tended to enforce a widening separation between British and Indian communities. In particular, these decades saw a move away from once more-common forms of interaction between white men and Indian women: sex, cohabitation, and sometimes marriage.

In imperial legend, perhaps the best-known story of sati is also a tale of cross-cultural romance. Around 1664, the East India Company merchant Job Charnock went to see a sati taking place at Patna. He was apparently “so smitten with the widow’s beauty, that he sent his Guards to take her by force from the Executioners, and conducted her to his own lodgings.” Charnock promptly married the woman himself. Some of his peers criticized the match and claimed that Charnock’s Indian wife “made him a Proselyte to Paganism”—but the couple had three daughters baptized in Madras, and seemed to enjoy a happy union. Charnock’s wife may have been with him in 1690, when he earned his entry in the history books by establishing a company factory on the site of present-day Calcutta. Some testament to Charnock’s border-crossing proclivities can still be seen there, in his decidedly Moorish mausoleum on the grounds of St. John’s Church.

Embroidered though it doubtless was, the tale of the Charnocks’ marriage was not unique. As Durba Ghosh astutely notes in her important new monograph Sex and the Family in Colonial India, other empires also anchored founding myths in episodes of interracial intimacy. La Malinche and Hernán Cortés, Pocahontas and John Rolfe, even Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson all represent versions of cross-cultural relationships that have been rendered as romance. Nor was this mixed-ethnicity union especially unusual within British India. In the early 1780s, fully one in three British wills registered in Calcutta mentioned a native female companion; by 1830, when these relationships were less acceptable, the figure was still one in six.

Yet most of these Indian companions—often called bibis or begums—remain ciphers in the margins of history, anonymous and little understood. Through meticulous and imaginative archival research, Ghosh manages to resuscitate the experiences of these most elusive women of the Raj—and to provide a fresh picture of gender relations across ethnic lines in early British India.

Though only a small proportion were ever formalized by marriage, domestic partnerships between European men and Indian women were a regular feature of early colonial society. “It is a very general practise for Englishmen in India to entertain a cara amica of the Country,” said one observer in 1805; and an early guidebook to India even offered instructions on how to make such arrangements.

One of the best-documented marriages of this era forms the basis of William Dalrymple’s justly popular White Mughals,8 a fascinating account of the relationship between James Achilles Kirkpatrick, British Resident in the court of Hyderabad, and the teenage noblewoman Khair un-Nissa. Begun through intrigue, then legitimized by marriage, their romance ended in tragedy: after Kirkpatrick died in 1805, his widow would be banished from her home, separated from her children, and abandoned by a new lover, to die “from a broken heart” at just twenty-seven. Dalrymple leaves us to interpret the fate of Khair un-Nissa as the betrayal of an empire that might have been. Those who hoped for a relatively tolerant empire were forced to cave in under the mounting pressures of bigotry and racism.

If one wants to understand the emotions, risks, and ambitions that inspired these attachments among people from different cultures, Dalrymple’s absorbing book is the place to turn. But Ghosh’s study, by virtue of its scholarly research, gives a more thorough description of the historical setting and provides a genuinely pathbreaking account of Anglo-Indian relations. She navigates skillfully between two common portrayals of Indian colonial companions. In her characterization, bibis were not only the “romantic figures” of high status showcased by Dalrymple but often had drab lives; and she does not subscribe to the general idea that eighteenth-century permissiveness gave way to nineteenth-century intolerance. Since at least the 1750s, she stresses, cohabitation with Indian women was common but “viewed as irregular,” and British men saw such relationships as potential sources of embarrassment. James Kirkpatrick himself, anxious to make sure his children would be accepted in England, arranged for them to be removed from their mother—evidence “that even the most cosmopolitan of men had parochial concerns when it came to their families.”

Ghosh does not, however, embrace the postcolonial view of such women as virtual “slaves,” so victimized by the colonial state as to lose their ability to act or speak altogether. Native women may have been deprived of power by domestic and imperial patriarchies, but this did not mean that they were entirely suppressed. Indeed, as she brilliantly reveals, they left their marks in the archive too.

So how does one locate them? Many bibis and begums either remained anonymous (like Charnock’s wife) or were recorded by just one name, often a Western one. By combing through marriage registers, baptism records, and legal documents, Ghosh ingeniously identifies dozens of female native companions and traces their various points of contact with the colonial state. In one of her book’s many striking revelations, Ghosh analyzes the wills of bibis to show how they managed their hybrid lives (and hybrid property, since many owned European goods), and recorded their relationships with Europeans, Indians, and Eurasians alike.

Court cases provide another indispensable seam of evidence. The appearance of native Indian companions in civil and criminal cases (such as property disputes or domestic violence) confronted the colonial legal system with complicated questions of jurisdiction—did these women fall under the purview of British courts or India’s separate Muslim and Hindu courts?—and the challenge of balancing British versus Indian testimony and demands. Of all the arms of the colonial state, however, the military was perhaps the institution with which native women came into closest—and most mutually beneficial—contact. The state relied heavily on native women, who acted as sex workers and companions for the troops. In turn, the military accepted “paternal responsibilities” of its own by granting pensions to soldiers’ widows and establishing orphanages for their mixed-race children.

Ghosh’s remarkable detective work succeeds in rescuing an entire group of marginalized figures from British and South Asian amnesia, if not outright denial. Her work provides a fine methodological example of how to allow “the subaltern to be heard and understood.” Her discoveries benefit greatly, too, from her attention to comparisons within and beyond the British Empire. General William Palmer, who had his mixed Anglo-Indian family immortalized in an unusual portrait, had previously lived in the British West Indies, where he had fathered three sons by a Creole woman. The Anglo-Caribbean children of his first match all joined Palmer in India (where one of them married a Muslim woman), forming an intriguing and rarely explored link between the two most important regions in which Britain held imperial power in the late eighteenth century. This archival diligence and comparative approach, together with Ghosh’s careful attention to theories of gender and ethnicity, should make her monograph an invaluable model for investigations of similar issues in any imperial setting.

Sex and the Family in Colonial India triumphantly demonstrates that native women—the subalterns among subalterns—were not entirely without some capacity to act on their own in colonial India. But what, in the end, did their initiatives achieve? Ghosh concludes with a rather bleak assessment of their ultimate impact:

Native female subalterns contributed to the formation of early colonial institutions of governance…. Native women were often the silent, unnamed other that enabled the elaboration of various types of hierarchies and social anxieties, based on race, class, and gender.

In other words, by working within the British system—producing wills, appearing in courts of law, petitioning for pensions—these women actually ended up reinforcing the authority of the colonial state, and making themselves its subjects. Their ability to take independent action was subsumed, indeed traduced, by enduringly patriarchal structures in home and government alike. Might they have been better off silent?

One closes this book about family relationships feeling perplexingly uninformed about their human, sentimental qualities. Crucially, the kind of evidence Ghosh draws on does not lend itself to speculation about inner lives, motives, or emotions. As she notes, there are virtually no sources in English or vernacular languages that offer insight into the minds of the bibis themselves; and what few there are were produced “under highly regulated conditions.”

Nevertheless, one senses that her resistance to the style of romantic narrative one finds in White Mughals—well-justified though it is—encourages her to fall back a little too readily on recognized academic formulas, with their talk of “bodily discipline,” strategies, agencies, and abundant “anxieties.” Dalrymple and Ghosh are consciously reaching out to different audiences, yet one cannot help wishing that Ghosh’s exemplary scholarship were not so detached from the realm of emotions that Dalrymple’s own stunning research allowed him to tap into. It is easier for historians to write about power than about feelings, and to do so is also more approved-of professionally. But in real life the two are not so easily separated. Couldn’t the kind of influence that so rarely gets recorded—the influence that friends, lovers, and relatives exert on one another—have mattered in their own ways?

For a striking reminder of why some historical figures remain in the shadows, consider the contrast between the cross-cultural relationships that Ghosh traces in archives and the ample memoirs, letters, and diaries that Margaret MacMillan could use to bring her British memsahibs to life. It is as if these two groups of women existed in separate worlds, consigned to their own distinct private spheres. Indeed, in large measure this was the case; European men rarely included their Indian companions in social gatherings with European women present.

But now and then, the memsahibs and the bibis met. The only figure who appears in both these books is Lady Maria Nugent, who traveled extensively in northern India in the 1810s. Sophia Plowden could have been another, since her diary records not only her experiences as an early memsahib but, between the lines, the presence of native companions among her friends. One August day in Lucknow, the bibi of her acquaintance Mr. Johnstone “suddenly came here for Justice,” saying that Johnstone had been beating her and refused to let her leave.

A few months later Plowden noted another aspect of these relationships, when she visited her friend Mr. Bellas’s one-month-old baby daughter. Whether its mother was present or not she did not say, though she found the infant “the fairest and smallest Child I ever saw born of an Hindostauny Woman.” But the baby, sick since birth, died just two days later. Had she survived, this fair Eurasian girl might well have faced separation from her Indian mother and expatriation to distant England. Instead she became another phantom, perhaps another tombstone, and another thin line in the records of empire.

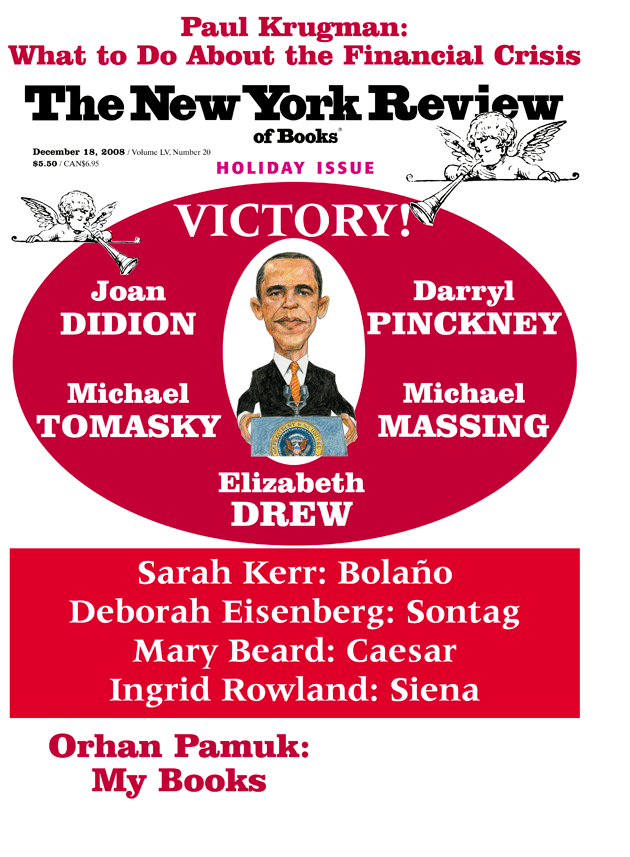

This Issue

December 18, 2008

-

1

Diary of Sophia Elizabeth Plowden, British Library: Asia, Pacific and Africa Collections, Mss Eur F127/94. ↩

-

2

Bernard S. Cohn, “The British in Benares: A Nineteenth-Century Colonial Society,” Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 4, No. 2 (January 1962), p. 180. ↩

-

3

Empire Families: Britons and Late Imperial India (Oxford University Press, 2004). ↩

-

4

H.E. Busteed, Echoes of Old Calcutta (Thacker, Spink, and Co., 1888), p. 335. ↩

-

5

“Edward Wheler,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, edited by H.C.G. Matthews and Brian Harrison (Oxford University Press, 2004). ↩

-

6

The Ruling Caste: Imperial Lives in the Victorian Raj (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006); reviewed in these pages by William Dalrymple, April 26, 2007. ↩

-

7

Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World (Random House, 2002); reviewed in these pages by Ronald Steel, November 20, 2003. ↩

-

8

White Mughals: Love and Betrayal in Eighteenth-Century India (HarperCollins, 2002). ↩