Peter Demetz, born in Prague in 1922, was “sixteen, going on seventeen” when on March 15, 1939, German troops, with the enthusiastic support of indigenous fascist groups, invaded the Republic of Czechoslovakia and occupied the city of his birth. As he writes in Prague in Danger, an exciting, one might even say thrilling, account of the six hellish years of Nazi rule that he witnessed, Demetz’s interests at the time were “politics, girls, movies, and jazz (in that order approximately).” Still, he was old enough to realize the enormity of what had happened, although, like most of his fellow Praguers, he did not foresee the full horror of the times that were coming.

Indeed, one of the most striking features of this history-cum-memoir is the record it gives of the peculiarly convoluted and insinuating process by which in modern times an immense nation devoured and digested a much smaller and weaker neighbor. The Anglo- Irish writer Hubert Butler, in his 1950 essay “The Invader Wore Slippers,” recalled how, “during the war, we in Ireland heard much of the jackboot and how we should be trampled beneath it if Britain’s protection failed us,” and how “our imagination, fed on the daily press, showed us a Technicolor picture of barbarity and heroism.” Supposing, however, the invader should wear “not jackboots, but carpet slippers, or patent-leather pumps, how will I behave, and the respectable X’s, the patriotic Y’s and the pious Z’s?” He then went on to consider the reaction of the populations of various statelets and regions of Europe to the Nazi invaders, and was particularly scathing about the way in which the people of the British-ruled Channel Islands accepted German occupation and settled back to their comfortable lives as before:

The readers of the Guernsey Evening Post were shocked and repelled no doubt to see articles by Goebbels and Lord Haw-Haw, but not to the pitch of stopping their subscriptions. How else could they advertise their cocker spaniels and their lawn mowers or learn about the cricket results?1

The German troops who marched into Czechoslovakia on the night of March 14–15, 1939, were certainly jackbooted, yet the response of the city, however angry and despairing the majority of its inhabitants may have been, was markedly subdued. Photographs of the occasion, when the German columns rolled through Prague, “show tears, grim faces, many clenched fists raised in the air, but also, especially later in the day, a good deal of curiosity about German weapons and motorcycles.” Within days, the Gestapo was reporting that “apart from a few incidents, the Czech population did not show any resistance worth speaking of.” However, Demetz laconically notes, “that was to change.”

In the ghastly year leading up to the invasion, Czechoslovakia had done its best to meet the Nazi threat, mobilizing its forces twice, in May 1938 and again in September of the same year, when the infamous Munich Conference between Germany and Italy on one side and Britain and France on the other resulted in an agreement ensuring “peace in our time,” as Neville Chamberlain deludedly had it, and in the process conceding to Germany the disputed Sudetenland, which, as Demetz writes, “deprived the Czechoslovak Republic of a major part of its historical territory, its principal fortifications against Germany, and much of its iron, steel, and textile factories.”

Unlike the comfortably circumscribed Channel Islands, pre-war Czechoslovakia, which had been in existence as a state only since the end of World War I, was a congeries of restive parts. Aside from the Sudetenland, its German-speaking majority led by the slyly plausible Konrad Henlein, there was the Slovak southeastern half of the country, where nationalism had become virulent. Hitler despised the Czechs and Slovaks equally, yet for his own purposes he hustled the less than unwilling Slovaks into declaring independence, initially as a German puppet state under the anti-Semitic Monsignor Jozef Tiso; then Hitler immediately summoned the Czech president, the elderly Emil Hácha, to Berlin and in a late-night meeting—Hitler had been watching his daily movie, for once not one of the Hollywood westerns that he delighted in, but a German-made comedy, A Hopeless Case—presented for Hácha’s signature a joint declaration under which the President would surrender his country more or less unconditionally into German hands. What no one on the Czech side knew was that Hitler had already prepared the invasion of Czechoslovakia in secret orders issued to the German army the previous year.2

Demetz’s detailed account of Hácha’s journey to Berlin and his fateful conference with Hitler and his henchmen, which opens the book, is the first of many tense set pieces, which might have been lifted straight from an Eric Ambler novel or one of Graham Greene’s early “entertainments.” The President’s party included his daughter, Milada Rádlová, acting as first lady, and Foreign Minister Franti ek Chvalkovský, “suspected by many of political sympathies for Italian fascism.”

Advertisement

There was also the president’s secretary, Dr. Josef Kliment, who was to develop his own ideas of collaboration with Germany; the loyal butler, Bohumil Pr íhoda, who had served President Masaryk in better times; and a police inspector. After a few members of the government had taken leave of the president, the special train, still unheated, left the Hybernská railway station at 4:00 p.m. Mrs. Rádlová had the distinct feeling that a shot was fired at the windows of her compartment when the train left Czech territory….

Demetz is largely sympathetic to Hácha, “a gentleman of the old school,” in his impossible predicament at this moment, shrieked at by Hitler on one side and cajoled by the greasily persuasive Hermann Göring on the other. The result of the confrontation was that Hácha, “who continued to believe that Germany’s military occupation of his country would be only temporary, put the fate of his nation into the hands of the Führer.” However, the genius of the Nazis was the subtly graduated manner in which they introduced repression, playing upon the psychology of the people, on their fears and their deeply, or shallowly, buried resentments; in this “carpet slipper” strategy, as in so many other ways, they were thoroughly modern, despite their trumpeted Blut und Boden dedication to the primitive.3

Hitler had promised Hácha that in a German protectorate the Czech peoples would enjoy “the most complete autonomy and their own way of life,” and his appointment of the internationally known diplomat Konstantin von Neurath as Reichsprotektor seemed a guarantee of some degree of civilized rule, though the native Czechs felt a premonitory shiver when they heard that Neurath’s second-in-command was to be Karl Hermann Frank, an ethnic German born in Karlovy Vary (Karlsbad) whose contempt for the Czechs was well known. If Neurath was Hitler’s curt nod to old Europe, Frank was Nazi Man personified, a beadily ambitious functionary who would carry out all orders handed down to him, no matter how cruel, adding his own twist of nastiness in the process.4

However, Prague did not realize the full nature of its fate until the arrival in the city of SS General Reinhard Heydrich in September 1941. After the German attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, Czech Communists, who had held back for the duration of the Hitler-Stalin pact, threw their full support behind the hitherto tentative resistance movement, for a start staging what the Office of the Reichsprotektor incredulously described as “events resembling strikes.” Clearly measures had to be taken, the first of which was the sidelining of Neurath and the appointment of Heydrich as “acting” Reichsprotektor, with the adroit Frank staying on as deputy. Heydrich, blond, polished, utterly ruthless, was Hitler’s parfit gentil knight, the very ideal of the Nazi Übermensch. “Heydrich,” Demetz writes,

was the ultimate terrorist untiringly active at his desk, and when Göring asked him to chair the Wannsee meeting about the final solution of the Jewish question, it did not come as a particular surprise to anybody in the Berlin bureaucracy.

Heydrich did indeed bring terror to Prague, imposing draconian civil restrictions and instituting a merciless drive against the resistance and, of course, the Jews. When he was assassinated in May 1942, by Czech parachutists flown in from London, Hitler immediately demanded that ten thousand Czech citizens be shot in reprisal, but in the end settled his vengeance on the village of Lidice, where, under the supervision of Frank, the entire male population was shot, the women sent to concentration camps, and the children dispersed, most of them to the gas chambers at Chelmno, after which the village was razed and all trace of its existence bulldozed over. The carpet slippers were well and truly off.

Demetz, who emigrated to America in 1948 and is Sterling Professor Emeritus of Germanic Language and Literature at Yale, writes of these matters with a remarkable combination of historical measuredness and personal immediacy—as he says, “I know, I was there”—dividing his book between alternating chapters on public events and his own experiences and those of his family. The fact that he continued to live in Prague throughout the war, first under Heydrich’s and then Frank’s rule of terror, is something of a wonder. “It would,” he writes, “have been exceedingly difficult to explain my special ethnicity (if I had one) in those years of either-or simplifications or requirements.”

He was what was defined under the Nazi race laws as a full-degree half-Jew. His mother’s family was Jewish, having moved first from the Bohemian village of Lukavec to the town of Pode brady—where Kafka’s mother was born—and then, just after 1900, to Prague. His father’s origins were in the South Tyrol, among the Ladin people, a Christian minority with their own language5 ; when the family moved first to Linz and then in the 1880s to Prague they switched to German, though Demetz’s grandmother continued to speak Ladin.

Advertisement

These two families, so different in origin, religion, and idiom, went on living in mutual distrust and condescension, the Jewish one in the New Town, where a few of my uncles assimilated to Czech culture, and the Ladini, with their baroque Catholicism, in a rabbit warren flat in the most ancient part of the Old Town….

Demetz wonders, wistfully, in which language his parents spoke to each other when their courtship began, the mother’s “fragmentary German” or his father’s “insufficient Czech”? “Perhaps they developed their own Prague language of love.”

Prague in Danger is peppered throughout with fascinating stories, from the larger world of the city but also from the smaller ones of his mother’s and father’s families. In a brief but splendidly written meditation on a photograph taken in 1912 of a family group on his mother’s side, Demetz manages to encapsulate something of the fate of the Jews of Europe in the first half of the twentieth century. What strikes us forcefully, as so often, is the ordinariness of these people—one of the strangest aspects of anti-Semitism is the premise that Jews are “Jews,” and therefore utterly other than “us”—with their ordinary joys and sorrows, secrets and legends, hopes and failures. Having recounted a racy anecdote about his adulterous Uncle Karel, Demetz opens the next paragraph with this sentence: “Another day four or five years later, the entire family was deported to Auschwitz, where Uncle Karel, Aunt Olga, and Jan died in the gas chambers.”

Yet the fate of the Jews was not uniform throughout Europe, and in the Czech lands it was singular in various ways. As Demetz points out, Czech anti-Semitism, although it has a long history reaching back at least to the beginning of the nineteenth century, in the late 1930s

emerged with new force, not at first as a prejudice based on racial assumptions, as in Germany, but rather as an illiberal and narrow view of ethnicity defined by habits of living and, above all, by language shared or not.

At certain levels, however, the usual depressing practices were manifest: early in the occupation, professional organizations of lawyers and doctors leapt at the opportunity to force out Jewish members. Under resolutions rushed through by these groups a few days after the invasion of March 15,

“Non-Aryan” law offices were now to be run by “Aryan” substitutes, and “non-Aryan” physicians were to be removed from public health institutions and clinics run by insurance companies….

Over the following months the ordinances of repression were slowly and agonizingly ratcheted up, until in late July the Reichsprotektor ordered the establishment of a Central Office for Jewish Emigration, with an administrator brought in from Vienna—Adolf Eichmann.

In 1942, in the widespread terror and slaughter after the assassination of Heydrich, Demetz’s mother was deported to the holding camp for Jews and other “undesirables” at Terezín. He took a few hours off from the bookshop where he was working, “and found my mother ready and dressed in her sporty costume, the yellow star, woolen stockings, and the heavy shoes she always wore for her Silesian and Austrian excursions in the hills.”6 His maternal grandmother had already been sent to Terezín, where, as he subsequently discovered, she died within a few weeks of arrival.

My mother had been in the transport of July 23, 1942, AAt, of which 947 died and 52 survived, and we did not know for a long time how she fared, but my father was in touch with a good Czech gendarme (never mind the fee) who told him that mother had stomach trouble and needed special pills…. One day my father was informed that my mother had died because of bleeding ulcers that could not be treated. Only much later did I receive a document from the Prague Jewish Community stating that she had died on June 26, 1943, at the age of fifty-one.

Demetz confesses that it was not easy to write about his father, a poet, theatrical director, and something of a scamp and a womanizer, though his reservations “combine with a recurrent melancholy about a life that hoped for much and was later totally distorted by circumstances of place and time, not to speak of history.” As other youths might yearn to run away with the circus, Demetz père, like Yeats, gave all his love to “players and painted stage,” and as a young man signed on as dramaturg with Prague’s German Theater, where over the years he battled hard to combat the city’s middle-class penchant for kitsch, putting on plays by Walter Hasenclever and Frank Wedekind, and working with the likes of G.W. Pabst, later to become one of the early and great movie directors, and the composer Alexander Zemlinsky. Gradually he drifted away from home and family, until eventually his wife sought a divorce—she later married again, a doctor, this time, who in turn took the last train to London when the Germans invaded, leaving her “alone and unprotected.”

Demetz’s half-reluctant fondness is apparent in his description of the results of the “ingenious plan” his father devised late in the war to avoid being drafted into the Volkssturm to defend Berlin, where he was then living, against the advancing Allied armies:

His plan was to “fall” in the darkness into a gaping bomb crater and injure himself slightly, but when he jumped, the crater proved rather steep and he broke both legs (Volkssturm, adieu). His girlfriend brought him from Berlin to a Prague hospital, where his Czech fellow patients and the doctors kept him, well bandaged and, for show, on crutches long after they were needed, as a kind of honest German pet until the May uprising in 1945, when he went home, seven minutes across Charles Square, limping a little, a picaresque hero of his time.

There are other delightful glimpses of this German-Czech Autolycus, culminating in a truly Shakespearian seriocomic encounter in the woods on the Bohemian-Saxon border in the spring of 1945. Earlier that year young Demetz, having been rounded up at last as a “half-Jew,” had been sent to a labor camp there, first cutting timber and later simply scavenging for potatoes in order to keep from starving. One day when he was marching with other prisoners to work, a man stepped out of the trees, “clad in a city winter coat, black hat, silk scarf, and elegant half shoes, as if stepping out of the Prague Café Savarin.” It was, of course, father, bringing news of the family and the Allies’ advance, and the gift of a stick of dry salami.

We walked together for a while, my astonished colleagues and I and my father, the only person from the outside ever to infiltrate our isolation, and at another bend in the road, he jumped into the trees again and disappeared as quickly as he had come.

It is impossible not to see in this figure, or at least in the author’s elusive yet vivid portrait of him, a shadowy personification of Prague itself—“I love and hate my hometown,” Demetz tells us in the opening words of Prague in Black and Gold. As he points out in the preface to that book, his sweetly nostalgic memories of the city of his youth are counterpointed by “more disturbing images,” for instance of the printed daily lists of Czechs executed in reprisal for the assassination of Heydrich, or of his mother in her sturdy shoes on her way to Terezín.

“Many of my European colleagues who like to write about Bohemian affairs have an easier time, unburdened by memories that make the heart ache and the stomach turn,” memories not only of the Nazi occupation but of the spring of 1948, after the Communist takeover, when he had to watch “some of my most admired teachers instantly revise their ideas rather than risk an honourable place among the hapless opposition.” Recalling a poem of Kafka’s in which Prague’s greatest literary son speaks of walking across the Charles Bridge and softly resting his hands on the old stones, Demetz notes, in bitterness and sorrow: “I always believed that he tried in that gentle gesture to keep the blood of many brutal battles from oozing out.”

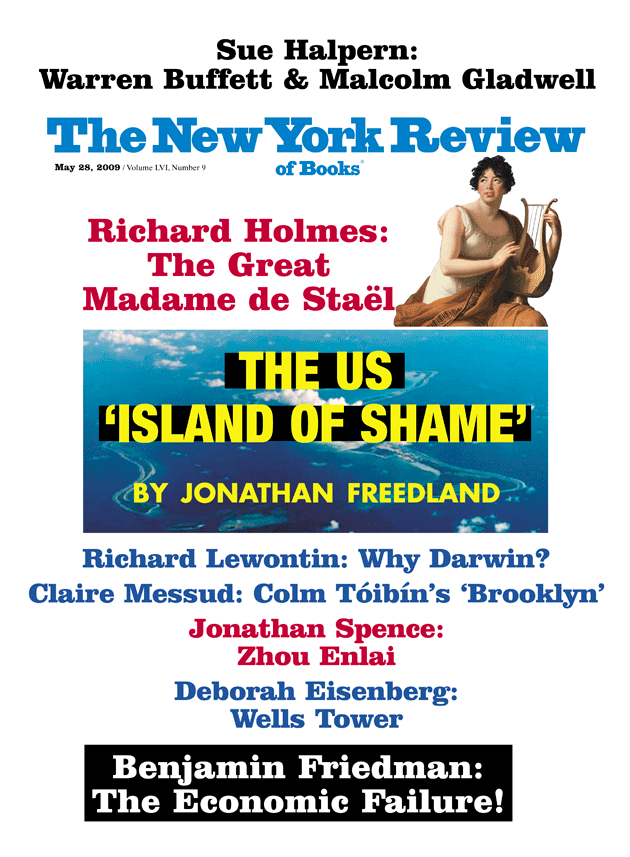

This Issue

May 28, 2009

-

1

See my review of Butler’s essay collection, Independent Spirit (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1992), in the June 12, 1997, issue of The New York Review. ↩

-

2

Demetz reports that no one believed a warning by the head of army intelligence, Colonel Franti ek Moravec, that German military occupation was imminent; Moravec’s response was to gather his officers and take a KLM flight to London. ↩

-

3

See, for instance, the diaries of Victor Klemperer in Germany and Mihail Sebastian in Romania, which provide detailed, day-by-day records of how the Nazi regimes gradually introduced restrictions against the Jews, taking away their bicycles one day, banning them from public transport another, and so inexorably on, until a point arrived at which mass deportation to the camps seemed the logical final step. ↩

-

4

He was hanged at Pankrác Prison in Prague on May 22, 1945. ↩

-

5

Not to be confused with Ladino, the Judeo-Spanish language spoken by Sephardic Jewish communities such as the Bulgarian one into which Elias Canetti was born. ↩

-

6

Those walking shoes remain a potent emblem for Demetz, and appeared earlier on the first page of Prague in Black and Gold (Hill and Wang, 1997), his superb history of the city from earliest days up to the funeral of T.G. Masaryk, first president of the Czech Republic, in 1937: “I recall an aging woman with sturdy shoes and a full rucksack (my mother) riding a shabby tramcar of the No. 7 line to the assembly hall from which Jews were transported to the camps, never to return….” ↩