1.

The two action-packed and densely argued histories by Brian DeLay and Karl Jacoby concern themselves with the terror, carnage, and widespread desolation suffered by the citizens of northern Mexico and the American Southwest, mainly in the second and third quarters of the nineteenth century. This terror was wrought for the most part by Apaches, Comanches, and other raiding tribes of the plains and deserts. It may not have produced a thousand deserts. But it produced some.

Both DeLay and Jacoby deal with broad swatches of history, though Jacoby slowly narrows his focus in order to illuminate a single event: the Camp Grant Massacre, which took place near Tucson on April 30, 1871. Members of three cultures—white, Mexican, and Papago-Pima (who now prefer to be called the Tohono O’odhams) did the killing. The victims, the fourth culture in this dark story, were Apache.

Both authors acquit themselves well, as they produce histories which require of them much cultural, political, military, and linguistic insight. I’ll start with the beheadings. There is, in the Frontier Army Museum, in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, a rare Kiowa calendar. The Kiowas appear to have kept their calendar-worthy events to two a year, one for winter and one for summer. The summer entry for 1833 translates simply as “the summer they cut off their heads.” The beheaders were probably Osage, and the victims women and children of the Kiowas, whose hiding place had been discovered.

This brief entry in a Native American calendar reminds me of nothing so much as—well—the headlines. Last year in Tijuana, Mexico, nine headless bodies were discovered; the heads, in plastic bags for ease of delivery, were nearby. (The Kiowa heads, I believe, were in pots.)

A few years earlier, in Uruapan, Mexico, a few heads were easily delivered by the picturesque method of rolling them into a popular dance hall. Uruapan is a place where assassins flourish, as they do up the Rio Grande in Juárez, a city where more than three hundred young women have disappeared since the mid-1990s.

And this autumn, in the humble Mexican border town of Nogales, Sonora, an hour from where I write, a pitched battle broke out downtown between the police and the drug cartels, leaving almost a dozen dead and no doubt scaring the hell out of the day’s tourists, who had casually strolled over to buy a few trinkets, eat some huevos rancheros, and get their Valium prescriptions refilled on the cheap.

2.

In fact our border with Mexico has been dangerous from the day it became a border. Cormac McCarthy’s justly acclaimed Blood Meridian deals with the border country in the period of transfer, and if that doesn’t scare you his more recent look at the border, No Country for Old Men, probably will. Settlers, travelers, diplomats, surveyors, military men, and even the outlaws themselves learned to tread cautiously in northern Mexico, the vast area that had been, in turn, New Spain, then (after 1821) Mexico, then (for nine years) Texas, then (1846–1848) a war zone, and, finally, thanks to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848, Mexico for good.

Almost immediately, not satisfied with the sizable bite we had just taken out of the continent, the US added the Gadsden Purchase (1853), which The New Encyclopedia of the American West1 rather brutally describes as “a wedge of territory between Texas and California,” some of which became Pima County, Arizona, whose county seat is Tucson.

Since I belong to that unfortunate generation of students who had to take Texas history four times just to get out of high school, I’m not going to drag up Cabeza de Vaca or much else that’s happened in Texas since his arrival. A happier route to DeLay and Jacoby would be to first consider the amazing surge of quite demanding scholarship that has been written in regard to the Comanches. T.H. Fehrenbach’s readable history appeared in 1974, generating little excitement. But then, in the mid-1980s, the bright star of revisionism beamed down on Boulder, New Haven, and other fertile sites; now we have studies of the Comanches from Thomas Kavanagh, Stanley Noyes, Gary Clayton Anderson, Pekka Hämäläinen, Brian DeLay, and several others.2 Karl Jacoby is interested in them too, but his study is naturally more focused on the western Apaches and their neighbors the Tohono O’odhams; a large number of the latter were more than happy to help out the raiders who hit Camp Grant by using their lethal mesquite or ironwood clubs to crack Apache skulls.

Like the Comanches, the Apaches were a many-branched people; both tribes brought much suffering to the almost defenseless villagers of northern Mexico. The Tohono O’odhams called the Apaches ‘O:b, “enemy”; the Zunis called them a ‘paču, “enemy.” It’s possible that the Comanches got their public name from the Ute word komatíca: “enemy” again, or, more literally, “anyone who wants to fight me all the time.” To themselves the Comanches were numunuu —the western Apaches were the Nnēē.

Advertisement

These oddments of Native American nomenclature suggest why the current generation of western historians seems more intellectually rigorous than those that came before it: historians have at last awakened to the folly of attempting to define or describe a native people without becoming as knowledgeable as possible about their tribal language.

The Apaches, after all, were pretty well studied by the 1980s and earlier by Angie Debo, Edwin Sweeney, Dan Thrapp, Don Worcester, C.L. Sonnichsen, and others—none of them slouches. But I wonder if they would have attempted a passage like this, from Brian DeLay, about Kiowa terms for New Mexicans:

Kiowas called New Mexicans K’o´pt’a’ka´i. The first element, k’o´p, means “mountain.” The second, t’a’ka´i, is common to all the Kiowa terms for specific groups of Mexicans. Its literal meaning is obscure but might be rendered as “mule-people.” By the late nineteenth century t’a’ka´i was more often translated as “whiteman,” though the term identified cultural difference, not skin color (hence the term Ko´ñkyäo´ñt’a’ka´i, literally “black whitemen,” to refer to Africans).

Such a passage also shows what a distance the Kiowas and their fellow tribespeople kept from Spanish itself, which, after all, had been spoken in New Mexico for a very long time.

John Wesley Powell, the pioneering explorer, geologist, and ethnologist who guided the Bureau of American Ethnology in its early years, implored his field workers to get accurate native American vocabularies and, when possible, grammars; they saved traces, at least, of many tribal dialects. But the story of the dwindling away of native languages is not a pretty one—our linguistic imperialism has been quite arrogant, calling tribes names they don’t call themselves, and getting by with a few marquee names that were not the names their tribesmen used for heroes: Crazy Horse from Tashunca-uitco, Sitting Bull from Tatanke Iyotake, and Geronimo from Goyaałé (and variant spellings).

By contrast, there is the admirable program started by the Navaho poet and educator Rex Lee Jim at the Navaho Community College in Tsaile, Arizona. Rex Lee Jim has been teaching college-level students in Navaho, an experience that both teacher and pupils find arduous but worth it. Rex Lee Jim, educated at Princeton and Middlebury, may be better known in Russia and China, because of his educational efforts, than he is here, and he may prefer it that way.

Brian DeLay and Karl Jacoby are certainly aware of the importance of nomenclature. DeLay begins his study with a note about names, and Jacoby ends his book with a really splendid glossary, in several native languages. I once wrote about the Camp Grant Massacre myself and think now that I’d rather have Professor Jacoby’s glossary than my whole essay.

3.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848, formally concluded our war with Mexico. In territory gained it ranks third among our land grabs, after the Louisiana Purchase (1803) and the acquisition of Alaska (1867). The southwestern border became the middle of the channel of the Rio Grande; where exactly the border would leave the river and strike west to the Pacific was not immediately settled.3

The engaging Rhode Islander John Russell Bartlett became the Boundary Survey’s commissioner in 1850; he had no great success with the boundary but did leave a charming travel book about his wanderings in Chihuahua, Sonora, and wherever his nose led him,4 after which he went back to Rhode Island and became librarian and bibliographer to the cultivated tycoon John Carter Brown.

If one takes a close look at terri- tories won and territories lost in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, a certain hedgehog-and-the-fox parallel becomes evident. The fox—us—gets many things: mountains and prairies and amber waves of grain. We get so much, indeed, that the hedgehog is hardly noticed, at least until we get to the (now) famous Article 11, at which point the hedgehog pounces, causing even seasoned historians to back up a step or two and say ouch.

Article 11 binds the United States to protect Mexico from the incursions of “savage tribes,” many of whom resided in the vast territory the US had just acquired. The US is also pledged to return any Mexican captives who can be rescued, and not to keep any such captives for its own use.

By signing the treaty, the US government bound itself to defend a border that, when adequately surveyed, would stretch from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico. Many Mexican officials considered that Article 11 was all Mexico got for its costly war, but had the US had either the muscle or the intent to enforce Article 11, Mexico might have had a pretty decent deal. At the time, though, the US could not protect its own citizens from the same terror by the tribes that were ravaging Mexico, and from the desolation they caused. There was in use a popular route from Texas into Mexico known as the Great Comanche War Trail; contemporary travelers who crossed it described it as being entirely barren of vegetation. That may have been a bit of an exaggeration, but clearly there were many routes that would lead raiding parties from the southern plains of the western deserts into northern Mexico, where the local people were easy prey.

Advertisement

Describing just how defenseless the peoples of northern Mexico were in this period is the main purpose of Brian DeLay’s study. The principal raiders, none of them acclaimed for their mercy, were Apache, Kiowa-Apache, Kiowa, and Comanche, though other tribes such as the Kickapoos occasionally took a hand. In the period right after the Mexican War the raids came thick and fast and took a grim toll.

What finally slowed the raids were factors that had little to do with the desire of the US to comply with Article 11. The first brake on the raiding was disease: cholera hit the Comanches in 1849, only a year after we signed the treaty. The Comanche leader Potsanaquahip, known popularly as Buffalo Hump (whom I have put in two novels and two miniseries), survived and remained a force, as did the Comanches themselves, who had about a quarter-century to go, but always as a slowly diminishing power. The whites learned how to fight these Indians. The Civil War was something of an interruption, but the tide clearly was turning, though war brought no immediate help to people in northern Mexico, who still had the Apaches to contend with; and the Apaches were a many-branched tribe, strung out from the New Mexican plain to the Gila River in Arizona. In Arizona they competed for scarce desert resources with the people who are now the Tohono O’odhams.

If it seemed absurd for the cowboys in Lonesome Dove to turn a horse herd in midswim because somewhere in the murky brown waters there was an international border, imagine how weird it must have been for native hunters, north or south, to be told that something they couldn’t see had become a reason for them to alter their ancient travel routes. Why is this cactus in the United States and the next one still in Mexico? What’s the logic that at a stroke, and for a time, made the Tohono O’odham cross-border Indians, with some of their territory in the US and some in Mexico?

For a quick, saddening look at the shambles our immigration policy has become, one need only drive west on Highway 86, from Tucson through the Tohono O’odham reservation, to the sad community of Why, Arizona. In assessing all the misery of both the Mexican-Americans and the not-much-better-off other Americans you will witness along the way, you will probably realize that Why, Arizona, is a community aptly named. That border issues remain intractable no one can doubt.

4.

The first third of Karl Jacoby’s Shadows at Dawn is mainly anthropology, but anthropology of a high order. As a study of the way of life and spiritual order of the Tohono O’odhams I have seen nothing to equal it. The Tohonos, as he makes clear, are gifted desert agriculturalists, prudent in the extreme when it came to preserving their foodstuffs. I own a Tohono granary basket and would not want to be the one who had to harvest all the grain it could hold.

That they would come into conflict with the western Apaches and Mexicans and whites was inevitable, because all three were trying to live within a difficult and demanding space. Apaches had some agriculture, too, but many bands preferred raiding—easier work. They hated and were hated by whites, Mexicans, and the Tohonos all three. Children of the Apaches were taken and enslaved, mostly by Mexicans, and bitterness deepened.

One of the best accounts of life in southern Arizona at this time is Raphael Pumpelly’s classic Across America and Asia (1870). Pumpelly was a mining engineer who came overland to Arizona by stagecoach from Gal-veston. No funnier account of stagecoach travel in the Southwest has ever been written. Mark Twain would have envied it.

In the late 1860s the entire territory shook with violence, and the US military was closer to being part of the problem than of the solution. The District of Arizona was then under the command of Colonel George Stoneman, who found Tucson to be too hot and sticky; Colonel Stoneman preferred to govern from Los Angeles. Camp Grant, not far from Tucson, was being run by young Lieutenant Royal Whitman, who was becoming very nervous about the number of Apaches who were crowding around his small headquarters. They were seeking safety from raids, and there was no shortage of raiders. Lieutenant Whitman informed his superiors by letter of this more and more alarming situation, but the lieutenant failed to summarize his letter’s content in the limited space provided, and thus the letter was rejected. Lieutenant Whitman counted the Indians every other day and doled out such rations as he had. The Apaches behaved well, but more and more of them came. In Aravaipa Canyon and the hills not far from the camp, as many as five hundred may have crowded in.

The overcrowding of Camp Grant with safety-seeking Apaches provided the people in Tucson who favored extermination—which was most of its citizenry, whether white, Mexican, or Papago—a chance to strike. They set aside their differences, which had previously been intense, and decided to act. The names of the conspirators —DeLong, Elías, Oury—mean little now, but the massacre they led means much. Though the killers—“shadows”—left town in small groups, they were not small enough to elude the attention of soldiers at Fort Lowell near Tucson, whose commander dispatched a rider to warn Camp Grant of trouble. The messenger arrived at 7:30 AM, as Lieutenant Whitman was having coffee.

But the shadows had moved out at dawn; when the first soldiers got to the Indian encampment, about 140 Apaches, mostly women and children, had been shot, stabbed, or clubbed to death. The leader they had most hoped to kill, Es-him-en-zee, was away, as were the men of the tribe. Es-him-en-zee came back to find some seven members of his family dead, and twenty-nine young children taken captive into (mainly) Mexico. These abductions engendered as much bitterness among the Apaches as the deaths themselves, and rescue efforts were prolonged.

Karl Jacoby fills in this grim story better than any other writer so far. A constant in our warfare with the Indians was the inability of the soldiers to tell Indians apart, or to believe that different branches of a many-branched tribe such as the Apaches had different temperaments and ways of life. The situation in Arizona didn’t improve much until General George Crook went there, studied the dispositions and attitudes of the various Indian bands, and sorted things out, to the extent that they could be sorted—for example, taking measures to decrease tribal warfare and to prevent further massacres such as the one at Camp Grant. They didn’t stay sorted, but that was not General Crook’s fault. At least he tried, and many others didn’t.

What did begin to change around the time of the Camp Grant massacre was that the American press suddenly became a force in our politics. Local coverage of what happened at Camp Grant followed the usual they-got-what-they-had-coming line; the locals were shocked to find out that the rest of the nation didn’t see it that way. There was outrage in the East. President Grant called what happened “murder, purely,” and forced an investigation. It had not previously been a crime to kill Apaches, but this time, thanks to the newspapers, the law got its hooks into the case and many violent acts were brought to light that the locals—particularly the participants—had hoped would stay hidden. This is not to say that anyone actually went to jail, but about one hundred men were indicted. A jury was formed, testimony was taken. A Tohono O’odham named Ascension was the only Native American to speak at the trial, and he spoke of the long, long cycle of violence between his people and the Apaches.

The Camp Grant trial is remembered today mainly as a legal curiosity. There were about one hundred defendants, and it took the jury only nineteen minutes to acquit.

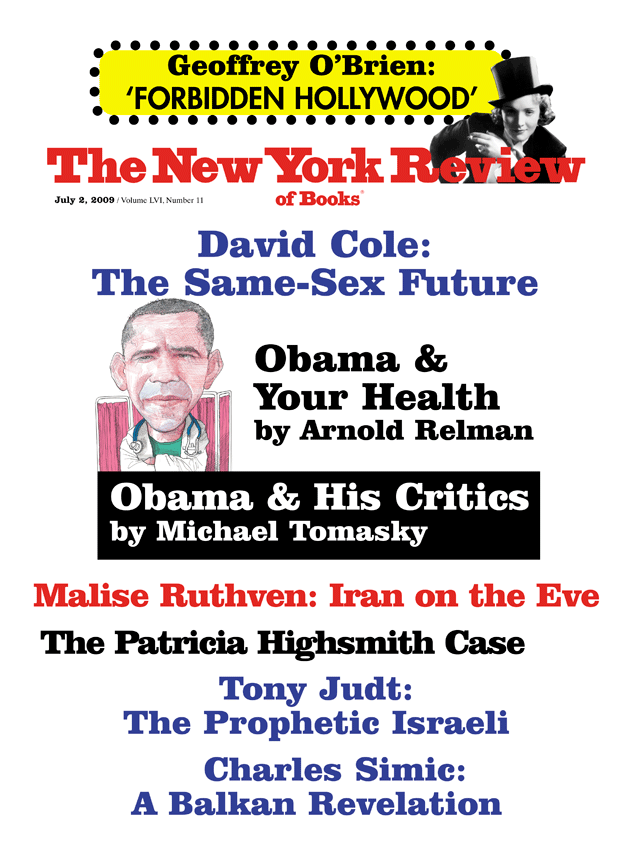

This Issue

July 2, 2009

-

1

Edited by Howard R. Lamar (Yale University Press, 1998); see my review in these pages, October 22, 1998. ↩

-

2

See my recent discussion of Comanche history in my review of Hämäläinen’s The Comanche Empire (Yale University Press, 2008), The New York Review, May 29, 2008. ↩

-

3

A minor inconvenience of the mid-channel border was that during the making of my miniseries Lonesome Dove (1989) the stolen horses that were supposed to enrich the Texans were actually swimming toward Mexico and had to be turned in midstream, a feat the cowboys doing the turning will not soon forget. The brilliant cavalry officer Ranald Slidell Mackenzie twice took his men across that river, with at best ambiguous sanctions, and would have laughed his head off had he known of this. ↩

-

4

Personal Narrative of Explorations and Incidents Connected with the United States and Mexican Boundary Commission, two volumes, 1854. ↩