When, last summer, YouTube disseminated from Tehran the extraordinary cell-phone images of the young woman named Neda as she expired from an apparently random bullet at a pro-democracy demonstration on June 20, 2009, perhaps few thought first of all of Shahriar Mandanipour’s highly literary metafictional novel Censoring an Iranian Love Story, published in the United States just six weeks previously.

And yet Mandanipour’s novel—his first to be translated into English, and a work directed, in part, at a Western audience—opens with a prefiguring of just such a tragedy. At the book’s outset we see a young girl, a student, as yet unnamed (she will prove to be Sara, protagonist of the narrator’s novel-within-a-novel), standing on the edges of a demonstration bearing a placard with the somewhat mystifying slogan “Death to Freedom, Death to Captivity.” Of her we are told:

The girl does not know that in precisely seven minutes and seven seconds, at the height of the clash between the students, the police, and the members of the Party of God, in the chaos of attacks and escapes, she will be knocked into with great force, she will fall back, her head will hit against a cement edge, and her sad Oriental eyes will forever close…

In short, like Neda herself, Sara is fated to sacrifice her life simply because she is standing there, then.

The novelist-narrator then proceeds to introduce Sara’s suitor, a young man named Dara, whose attentions will lure her away, thus diverting the course of history and sparing Sara death on this day. It is clear from the novel’s outset that what seem like Calvinoesque intellectual literary games are, in an Iranian setting, played for far higher stakes: Mandanipour’s narrator writes in an attempt to divert the course of history. He writes even a love story—perhaps especially a love story—to save lives.

Mandanipour wants us, his Western audience, to understand that in contemporary Iran, there is no boundary between realism and surrealism. As Sara idles at the demonstration’s edge, the secret police monitoring the event on their wireless radios pay her particular notice: “Watch her with extreme vigilance and caution,” they say.

This is most definitely a new conspiracy and a new plot for a velvet revolution orchestrated by American imperialism… Keep her under surveillance but do not let her suspect anything. Let her think she doesn’t exist.

The apparent comedy of these lines is bleak indeed when you understand that Mandanipour’s imagining is nothing if not real: you have only to read the accounts of those who have actually suffered at the hands of Iran’s secret police (such as Haleh Esfandiari, whose memoir I reviewed in these pages last fall*) to appreciate their obsession with conspiracies and the possibility of an American-sponsored “velvet revolution.” Then, too, there is the irony of “Let her think she doesn’t exist.” Sara doesn’t exist, of course: she’s a fictional character, a fact of which Mandanipour will remind us innumerable times. Even so, she inhabits a world—that of contemporary Iran—where an individual aims not “to exist,” but ” not to exist,” where existence itself implies a dangerous, perhaps fatal, interest on the part of the authorities, and where invisibility is always the goal. Sara’s world could not be more diametrically opposed to our own; in this sense, her realism is our surrealism.

Importantly to Mandanipour, that strange state of unreal reality has its most notable precedents, for West- erners at least, in literature: in Dostoevsky and Gogol, to both of whom the novel alludes explicitly and, in the case of Dostoevsky, repeatedly. The chief literary censor with whom the narrator has to tangle is “a man with the alias Porfiry Petrovich (yes, the detective in charge of solving Raskolnikov’s murders).” But there are also precedents in contemporary fiction like Milan Kundera’s, or in film; and again, importantly for the novel’s frame, in classical Sufi poetry, such as the love poem Khosrow and Shirin, written nine centuries ago by Nizami and telling of the romance between a great Persian king and an Armenian princess. This narrative will form the book’s third central strand, the other two being the musings and explanations of the novelist-narrator and the unfolding of Sara and Dara’s relationship, the novel-within-a-novel, set in boldface type and often interrupted by strikings-out and elisions.

The narrator explains these emendations early on:

I guess by now you have realized that the crossed-out words in the text are my own doing. And you must know that such a fanciful eccentricity is not postmodernism or Heideggerism. In fact…

And by now you have surely grasped the significance of “…” in Iran’s contemporary literature.

And further:

Advertisement

When Sara reads a contemporary story, she reads the white between the lines, and whenever a sentence is left incomplete and ends with three dots like this “…,” her mind grows very active and begins to imagine what the eliminated words may be.

Or more dramatically:

The moment a reader, especially an Iranian one, sees these three villainous dots, a reaction similar to the chain reaction triggered by nuclear fission of the uranium atom takes place in his mind, and it results in the release of terrifying nuclear energy.

There follows here a comic riff providing examples of readers’ extravagant imaginings of what originally lay behind such ellipses, with the result that

Iranian writers have become the most polite, the most impolite, the most romantic, the most pornographic, the most political, the most socialist realist, and the most postmodern writers in the world.

Mandanipour’s novel is indeed postmodern, a collage of the factual, the historical, the fantastical, the fictional, the metafictional, and the cartoonish. On one level as a love story it unravels from the tragic to the preposterous, as Sara and Dara struggle to unite first against the imbalance of their respective social positions and the insanity of their culture’s strictures, but eventually against hunchback midget corpses, mythical armies, and hashish- inspired assassins. On another level, as a metafiction the book elaborates interesting analogies between the plight of the censored writer (whose censorship, as we know from the narrator’s own ellipses, perforce exists in his own head: he doesn’t merely suffer at the hands of the censor, but at his own, in anticipation of the censor) and the plight of his characters. Like Sara or Dara he is a character vainly resisting a fate ordained from on high.

On still a third level—and this, ultimately, is the most lucid and affecting aspect of Mandanipour’s ambitious and challenging project—the novel explicitly provides a Western reader with a primer to contemporary Iranian culture: “I don’t like to constantly interrupt my story’s progress to offer explanations,” the narrator laments at one point.

But it seems I have no choice. Some things and certain actions in Iran are so strange and outlandish that without explaining them it is impossible for an Iranian story to be well understood by non-Iranians.

The ironies of an Iranian primer—a book that will teach us not how to read, but how to read Iran—are inherent in the very names of the love story’s characters. Sara and Dara (“Don’t ask, I confess, the names are pseudonyms”) are names taken from primary school textbooks in the time of the Shah: characters who, following the revolution, first changed (“there was a headscarf covering Sara’s black hair…”) and then vanished (“another girl and boy replaced them—siblings with no recollection of the Shah’s corrupt and tyrannical regime”). And the unfolding of Sara and Dara’s love affair is organized around incidents or encounters that can best instruct the West about this alien culture.

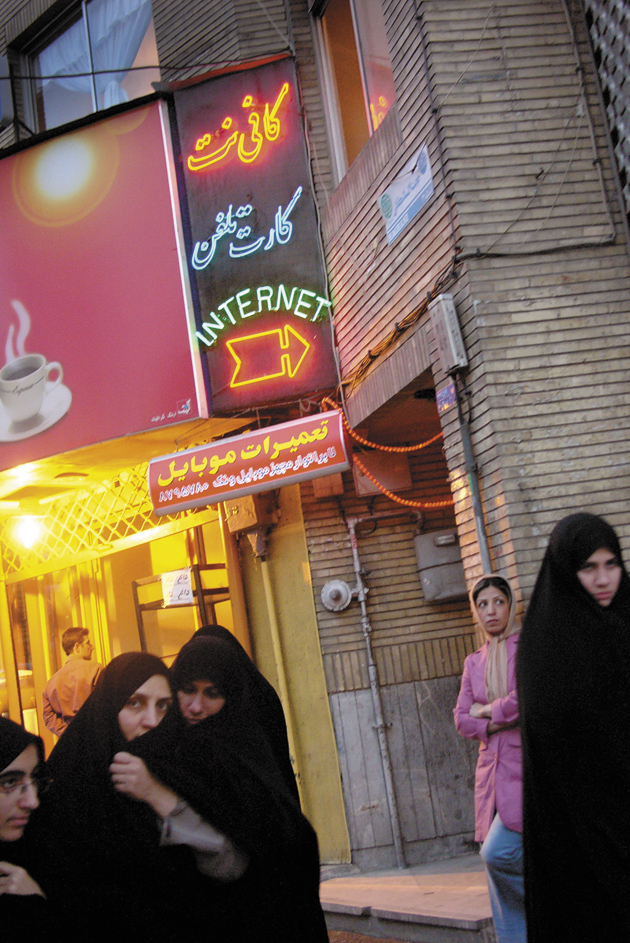

For instance, Sara and Dara go for a walk together, almost, it seems, in order for the narrator to inform us about the penalties for young couples apprehended in public, as well as about the ruses they use to avoid it. They visit an Internet café, and it is explained that there, too, they must dissemble when the police arrive. But even before things get that far, the narrator vents his frustration at his Western readers’ costly ignorance:

Ask me if there are Internet cafés in Tehran.

Of course there are. What image do you have of Iran? Are you like that person I once met at the literary festival in Stavanger, Norway, who after my long-winded talk on modern and postmodern literature in Iran asked:

“Have you heard of the Internet in Iran?”

Or like my son’s classmate in Providence, Rhode Island, who asked him:

“You don’t have cars in Iran, you ride camels; why do you want to make a nuclear bomb?”

Sara and Dara’s story, and their histories (Dara has spent time in prison, in solitary confinement, and has consequently been unable to complete his filmmaking studies), provide ample opportunities for cultural instruction. They go to the cinema together; they visit street peddlers selling books; they enter a bridal shop. Such vignettes are not simply early steps in a love affair, they are also the scenes from a first-year language course, the means by which novices can acquire both the necessary primitive vocabulary and the general knowledge required to approach an unknown culture.

Censoring an Iranian Love Story, in all its playfulness and sometimes baffling complexity, thus provides American and European readers with an introduction unlike any other to Iranian literary history (we learn not only the story of Khosrow and Shirin, but are apprised of the more recent writings of authors like Hooshang Golshiri and Ahmad Shamlu, and even of the earlier writings of Mandanipour himself) and also to Iran’s present reality.

Advertisement

The ironies, for Mandanipour, are rife. Having come to the US as a writing fellow at Brown University in 2006, Mandanipour wrote this book in Farsi, in the United States, and has dedicated the novel in part to his excellent translator, Sara Khalili (“without whose faith and fellowship writing this novel would not have been possible”). As his alter ego explains:

I am an Iranian writer tired of writing dark and bitter stories, stories populated by ghosts and dead narrators with predictable endings of death and destruction. I am a writer who at the threshold of fifty has understood that the purportedly real world around us has enough death and destruction and sorrow, and that I did not have the right to add even more defeat and hopelessness to it with my stories.

But in seeking to do this—to write a simple and joyful Iranian love story—Mandanipour and his narrator must be thwarted:

I, with all my being, want to write a love story…. A story with an ending that is a gateway to light…. My dilemma is that I want to publish my love story in my homeland.

This last will not only prove impossible, but the publishing of this love story will, in reality, make it impossible, once and for all, for Mandanipour to return to that homeland.

The strangeness of the narrator’s direct address to the West is then unsurprising: to record the realities of contemporary Iran, whether inside or outside Iran, is to be banished forever, like a character in a classical poem. The love story of the novel’s title is that of Sara and Dara; but it is also that of Mandanipour and his native country, a love story that cannot, at present, end happily.

Mandanipour now lives in the United States. Like Haleh Esfandiari, he is persona non grata in Iran. Albeit reluctantly, but with considerable passion, he writes, in this book, to us, his new compatriots. But he writes for his old compatriots, his heart’s true love, against W.H. Auden’s dictum that poetry makes nothing happen, in the hope—may it not be vain—that he might alter the course of fate: that he might not only save Sara’s life, but, if not Neda’s, then the lives of the Saras and Nedas of the future. The first step, of course, is for us in the West to read, to listen, and to try to understand.

This Issue

April 29, 2010

-

*

Haleh Esfandiari, My Prison, My Home: One Woman’s Story of Captivity in Iran (Ecco, 2009), reviewed in The New York Review, December 3, 2009. ↩