It is no wonder that we know so little about the woman who was the world’s most famous actress for the best part of half a century. When Sarah Bernhardt died in 1923, almost half a million people lined the streets of Paris. Most of them had seen her on stage and in movies, performing as though each plot were a conduit for her own emotions and as though every play from Racine’s Phèdre to Dumas’s La Dame aux camélias had been written as a psychobiography of Sarah Bernhardt. “No temperament more histrionic than Mme Bernhardt’s has, perhaps, ever existed,” wrote the obituarist of the London Times. “To read her memoirs is to live in a whirl of passions and adventures—floods of tears, tornadoes of rage, deathly sickness and incomparable health and energy.” As Robert Gottlieb warns in his appropriately lively biography, “She was a complete realist when dealing with her life but a relentless fabulist when recounting it.”

Alexandre Dumas fils saw her deceitfulness as an essential part of her genius: “You know,” he said of the famously thin actress, “she’s such a liar, she may even be fat!” For Bernhardt herself, deception was not just a matter of theatrical illusion. Even as a child, she had reasons to conceal the truth. Her Jewish mother, Youle, who was either Dutch or German, was a wandering demimondaine—a polite term, in her case, for a prostitute specializing in wealthy men. Sarah, or Rosine, as she appears in some documents, was Youle’s third child: she had given birth to twin girls when she was only fifteen years old. All three were illegitimate, and all three may have had the same father, a naval officer from Le Havre. Whoever he was, he disappeared, never to return. The name Bernhardt was borrowed from Youle’s lover of the moment, “one of the wildest youngsters in the Latin Quarter.” He was called Édouard de Therard, and Bernhardt was his nom de guerre.

Bernhardt’s own version of her family background—a beautiful, neglectful young mother and a handsome father mysteriously detained in China—suggests a mind steeped in cheap melodrama, though perhaps the clichés simply fitted the emotional reality. Starved of parental affection, she became troublesome, tomboyish, and oddly prone to accidents. She fell into a fire and was “thrown, all smoking, into a large pail of fresh milk”; she flung herself in front of her aunt’s carriage and broke her arm in two places; she hit her classmates and cried herself into life-threatening fevers. She also assembled a gruesome little zoo of lizards, crickets, and spiders, which she gleefully fed with flies.

While little Sarah was learning to make herself the center of attention and—according to her memoirs—behaving like an actress-to-be, her mother was preparing her for a slightly different, though related, career. She was sent to a convent school in Versailles to become respectable and Catholic enough to follow her mother into the seamy side of high society. By the time Sarah left the school, her mother had succeeded in becoming the mistress of the Duc de Morny, the half-brother of Emperor Napoléon III. It was thanks to the duke that Sarah was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire to learn the art of acting, and then, surprisingly, after two years of only modest attainments, to the temple of classical drama, the Comédie-Française. She was probably sixteen years old (her year of birth is unknown), unfashionably and unhealthily thin, short (a little over five feet), and, according to some, too obviously Jewish.

Her first public performances took place in 1862, during the theater’s traditional showcasing of new actors. Her third performance was reviewed by the leading theater critic of the day, Francisque Sarcey. His review shows, first, that the young Bernhardt was remarkable only in her mediocrity and, second, that even a debutant actress might have to suffer astonishingly cruel treatment from her elders:

This performance was a very poor business…. That Mlle Bernhardt should be insignificant doesn’t really matter very much—she’s a debutante, and among the number presented to us every year it’s only natural that some should be failures.

Later, Bernhardt would surround herself with a menagerie of wild animals, including a cheetah, a wolf dog, an alligator, and a boa constrictor. It might have been a fabulist’s image of the vicious world of the Paris stage. Shortly after her debut, one of her younger sisters, whom Sarah had invited to the theater, accidentally stepped on the train of a senior actress, who slammed the little girl against a marble pillar and made her bleed. After slapping the actress and calling her a bitch, Sarah refused to apologize and stormed out of the theater, tearing up her contract. It was her first notable performance and, says Gottlieb, transformed her overnight “from a nobody into a scandalous topic of conversation.”

Advertisement

Her first professional performances as her mother’s apprentice were better appreciated. So many prurient tales were told about actresses that it is hard to believe any of them, but Gottlieb and Bernhardt’s other biographers present ample evidence of her parallel career as a demimondaine. At first, her mother served her up at dinner parties to wealthy old men or induced her to perform in “somewhat questionable entertainments in the homes of titled acquaintances.”

Edmond de Goncourt overheard a conversation in a Paris restaurant: “The Sarah Bernhardt family—now, there’s a family! The mother made whores of her daughters as soon as they turned thirteen.” For once, the gossip was more or less true. Sarah’s sister Régine died at the age of nineteen, “after a miserable life of neglect and prostitution.” Sarah seems to have taken a more businesslike approach to prostitution. She collected about her a group of male admirers whom (according to a rival actress) she called her “stockholders.” One of those investors may have been the father of her son, Maurice, who was born in 1864.

She was, in effect, performing to a small, select audience, and earning far more money than she would have earned in the theater. After leaving the Comédie-Française, she spent a year playing minor roles as an understudy at a boulevard theater and then another two years during which she hardly acted at all, yet she was soon wealthy enough to acquire a new apartment with a white-satin salon in the rue Duphot, not far from La Madeleine, in one of the most expensive parts of Paris.

Sex would continue to be a large part of Bernhardt’s life, either for its own sake or as a means of supplementing her income. Even in the 1870s, when she had made a name for herself, police spies reported high-ranking customers, including members of Parliament, “visiting” her apartment and leaving money and valuable gifts. It is a shame, therefore, that the information about her parallel career is so sketchy and monotonous: very little about the actual performances, and nothing at all about the practical arrangements.

Bernhardt herself was quite open about her conquests. Early in her acting career, says Gottlieb, she “inaugurated her lifelong habit of automatically sleeping with her leading men,” usually in the dressing room. The sheer numbers involved place her in the same amatorial league as Victor Hugo or Alexandre Dumas père. Hugo himself was probably one of her lovers. He recorded several amorous encounters with Bernhardt in his secret diary. Once, in 1875, he noted, presumably with relief, “S.B. No sera el chico hecho” (There isn’t going to be a baby).

It would be nice to think of Sarah Bernhardt as a pioneer, enjoying her triumphs in a world dominated by men. Her habit of sleeping with leading men sounds like a deliberate reversal of the traditional male actor’s droit du seigneur. However, the fact that, unlike Hugo or Dumas, she was incapable of achieving orgasm presents the “habit” in a different light. In 1874, in a soothing letter to a distraught lover who had failed to satisfy her, she described herself as “an incomplete person”: “I am just as unsatisfied the morning after as I am the night before.” As Gottlieb observes, even in bed, she was an actress, “simulating passion.”

Biography inevitably emphasizes the extraordinary, but there is probably nothing fundamentally unusual in her behavior. One of her modern biographers, Ruth Brandon, whose “measured feminist approach” Gottlieb praises, suggests that Bernhardt’s pleasureless promiscuity was a sign of her inability to trust or to love another person, and that, for her, the stage was “a form of natural therapy.”1 It would be trite to say that the fatherless child who was prostituted by her mother was punishing herself and that her famous death scenes were public acts of self- annihilation. But when Sarah Bernhardt, who was so famous for being extraordinary, finally took a husband, she did what countless women in her position have done: she married a man who not only didn’t love her but who also tried to destroy her—a morphine addict, “a spendthrift, a gambler, an obsessive womanizer, and a bigot.” This was a Greek aristocrat called Aristides Damala, who called his wife “that Jewess with the long nose” and made scenes at her performances. He fancied himself an actor, but his only obvious contribution to literature is that he was one of Bram Stoker’s models for Count Dracula. Gottlieb wonders, in the face of her inexplicable affection, if the ghastly Damala was the only man who could “give her sexual satisfaction.” If so, she paid a heavy price.

Advertisement

Bernhardt returned to acting in 1866, when she was taken on by the Odéon. In that more intimate theater with its younger, rowdier audiences, she quickly became a star. Her finest performances there came during the Franco-Prussian War, when she turned the theater into a hospital. Her hardheadedness and her fascination with death and the process of dying made her a useful nurse rather than just an inspiring presence. Real life was a rehearsal and reality itself an object of study. “Nothing fazed her,” says Gottlieb, quoting her apparently truthful account of her first act of mercy:

I raised my lantern to look at [the soldier’s] face and found that his ear and part of his jaw had been blown off. Great clots of blood, coagulated by the cold, hung from his lower jaw…. I took a wisp of straw, dipped it in my flask, drew up a few drops of brandy and blew them into the poor fellow’s mouth between his teeth.

Already a national treasure in her late twenties, she returned to the Comédie-Française in 1872. From then on, her life is a tale of hard work and ever-increasing celebrity. Bernhardt was not just an actress who became famous; fame was her profession. Henry James watched her perform in London and realized that he was seeing something more than an actress:

The trade of a celebrity, pure and simple, had been invented, I think, before she came to London; if it had not been, it is certain she would have discovered it. She has in a supreme degree what the French call the génie de la réclame—the advertising genius…. I strongly suspect that she will find a triumphant career in the Western world. She is too American not to succeed in America.

She succeeded, not just in America, but all over the world. Though she always performed in her native language, she regularly reduced audiences who understood not a word of French to a state of tearful ecstasy. They came to see not the play, but Sarah Bernhardt. She was fêted wherever she went. During a thirteen-month tour of the Americas in 1886–1887, she was given 13,000 acres of land in Argentina and a carload of guano in Peru. Her name was used to advertise soap, bicycles, and painkillers.

Gottlieb’s biography is part of a series titled “Jewish Lives,” but apart from some bigoted remarks by journalists in the United States and Australia, and anti-Semitic demonstrations during her tour of Russia, there appears to be surprisingly little to report on the subject. She publicly supported Émile Zola during the Dreyfus Affair, but escaped the general vilification that was meted out to other Dreyfusards. Her Jewishness was ultimately part of her exotic charm: “The cherished blood of Israel that runs in my veins impels me to travel,” she is supposed to have said, as though referring to a personal quirk. “I love this life of adventure!”

Despite “endless testimony about Sarah’s acting,” the “peculiar magic” of Sarah Bernhardt, as Brandon puts it, is extremely hard to recapture. The scratchy recordings and the jerky films only emphasize the remoteness of the past. (Bernhardt was horrified to see herself on film: she is said to have fainted at the sight of her aged self in La Dame aux camélias.) What strikes one about the recorded Bernhardt is precisely what she is supposed to have abolished: the well-rehearsed gestures, the grand, domineering stiltedness. Her breathless recital of Phaedra’s famous speech from Act Two of Racine’s Phèdre is more pedagogically than theatrically impressive: in her cavernous soprano voice, with a dying plunge in every line, she makes all the obligatory liaisons, enunciates the correct number of syllables, draws out the vowels to the precise length required by the emotion.

A student called May Agate who attended one of Bernhardt’s private classes found an instructress in place of an actress:

She never moved from her chair to demonstrate. She would explain, lecture to us…. What appealed to me in her teaching was the extraordinary application of common sense to the interpretation of every line, so that it never ceased to be a human being speaking.

The problem is, do we know how “a human being” spoke a hundred years ago? Even a perfect recording could not restore the familiar backdrop of the time, the contrastingly normal voices in the foyer, the daily pantomime of gestures and expressions, nor, of course, the theatergoers’ notion of what constituted a “natural” performance.

A plausible ghost of the great actress can be conjured up from reviews and from her own and other people’s memoirs: “her talent for endowing immobility with excitement,”2 her thrilling silences, the gestures that began at the shoulder and made full use of her long arms, her “face-acting” and her clever use of cosmetics, and above all, perhaps, the sheer stamina that enabled her, for instance, to simulate blindness by showing only the whites of her eyes for half an hour. Some of her startling appeal seems to have come from partially corrected faults: she had a tendency to speak with clenched teeth and had been advised at the Conservatoire to place little rubber balls in her mouth; she sometimes rushed through certain passages, mumbling and chanting them in a monotone, then suddenly rasping out the crucial word or phrase.

Gerda Taranow, whose excellent Sarah Bernhardt: The Art Within the Legend is practically a Sarah Bernhardt acting manual, describes her technique as a form of method acting learned at the popular boulevard theaters, combined with a secure foundation in the curriculum of the Conservatoire. It was because of this classical grounding that she was able to break the rules so effectively, speaking with her back to the audience or emphasizing the erotic potential of a role. Everyone knew that Phèdre was a drama of sexual obsession, but only Bernhardt made the sexuality explicit, says Brandon, “to the point of, at one moment, drawing her hands up the insides of her thighs.” Perhaps this was the fruit of those “somewhat questionable entertainments” of her youth. It was a far cry from the “dreary classicality…calculated to freeze the marrow” that Charles Dickens had witnessed at the Comédie-Française in 1856, a few years before Bernhardt entered the Conservatoire.

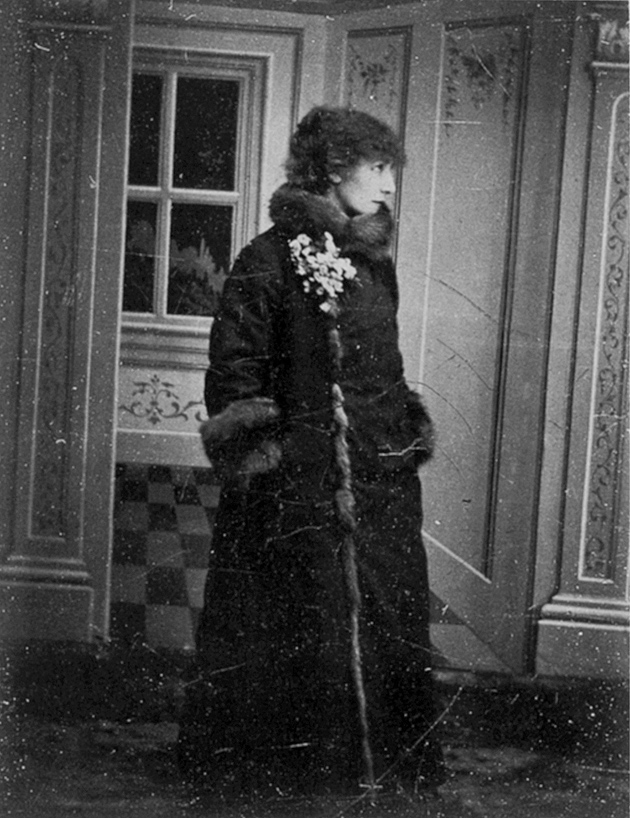

The power of her acting and her physical presence can only be imagined. Her offstage personality is probably even harder to convey. Gottlieb’s affable, anecdotal style suits the subject well. As the author of A Certain Style: The Art of the Plastic Handbag (1988), he has a keen eye for the seemingly trivial details that were essential elements of Bernhardt’s presence: the impressively ridiculous hats (one of them was crowned with a stuffed bat), the belts that dipped below the hips, the dresses that seemed to encircle her in a spiral, the furs and frills, the jewels and accessories that made her “a walking museum.”

Yet one suspects that, beyond the theater and the wardrobe, there is not a great deal to be said about the “real” Bernhardt. Her contemporaries were apparently quite happy to believe that she shared the violent passions of her favorite roles, and that everything she did, on or off the stage, was the result of histrionic frenzy. It seems obvious now that a woman who was in a constant state of passion would have been incapable of running a theater almost single-handedly, inventing and making up costumes, demolishing and recreating stage sets, lecturing the lighting engineers, directing plays, and managing her own fame.

Her tearful audiences might have been surprised to learn that her own conception of acting was diametrically opposed to their own. She believed that “the artist’s personality must be left in his dressing room; his soul must be denuded of his own sensations”:

Do not let us imagine for a moment that we can create an artificial exterior while maintaining our ordinary feelings intact. The actor cannot divide his personality between himself and his part; he loses his ego during the time he remains on the stage.

This methodical erasure of the self is one reason why Bernhardt is less interesting as a biographical subject than her spectacular performances would suggest. Her most enduring and successful affairs were always with her audience, and the dynamics of that relationship are almost impossible to recreate.

One revealing innovation that seems to have escaped her biographers was her abolition of the prompter’s box when she acquired her own theater, the Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt (now the Théâtre de la Ville), in 1899.3 Nothing was to impede the immediacy of her performance. That little head at the actor’s feet was an obtrusive witness to a private act, endlessly repeated. The “vast monotonies of temperament” of which the American theater critic Stark Young complained in her stage performances were a sign of a kind of contentment. The stage was, after all, a dependable source of satisfaction.

Again and again, the Sarah Bernhardt who had left her true self in the dressing room reduced her audience to tears and received the tribute of their adulation. It was the best kind of love a woman who had been so badly abused in her childhood could enjoy—passionately violent, calculated, vengeful, and founded in mutual respect. In 1923, as she lay dying, she learned that crowds had been gathering outside her house for several days. She smiled and said, with the peculiar affection of an actress for her audience, “I’ll keep them dangling. They’ve tortured me all my life, now I’ll torture them.”

This Issue

October 14, 2010

-

1

Ruth Brandon, Being Divine: A Biography of Sarah Bernhardt (1991; London: Mandarin, 1992), p. 120. ↩

-

2

Gerda Taranow, Sarah Bernhardt: The Art Within the Legend (Princeton University Press, 1972), p. 97. ↩

-

3

Henry Lyonnet, “Petites curiosités théâtrales: le souffleur,” Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire du Théâtre (1902), pp. 34–35. ↩