After three and a half weeks the “Secrets of the Silk Road” exhibition at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology—a collection of some 125 astonishing artifacts from the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region in China—continues as a ghost of its former self. Life-size photos now replace the original artifacts that have been sent back to China, and wooden replicas (constructed by the museum’s modeler) mimic its vanished mummies. The Chinese unexpectedly withdrew their exhibits. Yet in the brief weeks of its showing, the full exhibition was seen by an unprecedented 42,000 visitors, the opening hours were extended, and whatever politics prompted the Chinese decision resulted in more—but baffled—publicity.

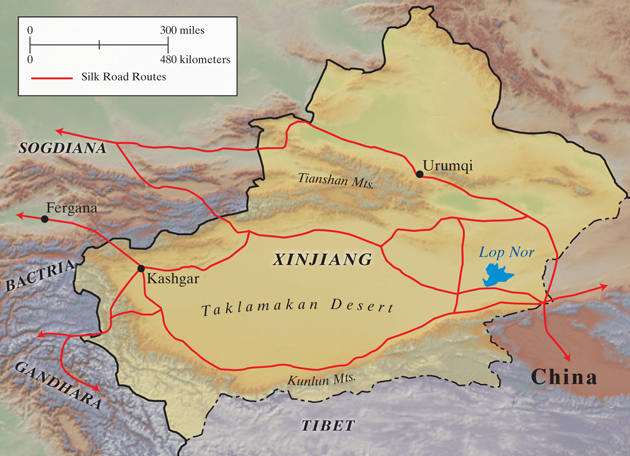

On the face of it the exhibition is more specialized and narrow than its Silk Road name implies. (The trade routes of the Silk Road interwove across all Asia from China to the Mediterranean.) Yet paradoxically the exhibition is also more ambitious. For it concentrates almost exclusively on the ancient civilizations of China’s giant northwest province of Xinjiang, a land divided between high northern grasslands and—crucially—southern desert, whose sands have preserved many artifacts eerily intact.

The provenance of this region’s early peoples is controversial. Traces of their presence date back to at least 2000 BC, and the direction from which they first reached the edges of Xinjiang’s bitter Taklamakan Desert is still uncertain. Some scholarly opinion locates their origins in the Andronovo culture of the Eurasian steppe, or perhaps still farther west on the fringes of Europe itself—and recent DNA analysis appears to support this.

But around the third century BC, the westward counterflow of Mongoloid peoples began in earnest, and some of the early sites in Xinjiang now lie a thousand miles within the borders of modern China. The complex ethnicity of the region’s inhabitants, the scattered sites of their settlement, and the intermittent centuries of their arrival all militate against their being better known. The culture and even the appearance of the earliest settlers—locked in uncannily preserved mummies—are not Chinese at all, but Caucasoid. They belong, astonishingly, with the West.

If there is a guiding theme in the museum’s presentation, it is the insistence on Western origins and influence. One of the most striking exhibits is a kneeling bronze warrior from the fifth century BC, a figure of Scythian extraction perhaps, or even Hellenic. The remains of a handsome tapestry (later sewn into a pair of trousers) feature a warrior of fleshy Europoid features and wide blue eyes, with a centaur cantering across the panel above (see illustration on page 18). The exhibition’s early robes, it is pointed out, have their closure on the left, contrary to the Chinese style; gold belt plaques echo those of Caucasoid nomads to the north; Sassanian coins signal trade with Persia, whose symbols of bull and boar appear in funerary garments; and as late as the Tang dynasty—between the seventh and tenth centuries—Chinese-made clay figures with high-bridged or heavy noses, twirling mustaches, and rounded eyes reflect a fascination with the region’s natives, whose peaked hats and ample beards betray them.

The exhibits include textiles of remarkable accomplishment—brocades, skirts, hats, trousers, quilts, pillows—with figurines, vessels, masks, pouches, gold plaques, eyeshades, jewelry, even preserved foods, which date from 2000 BC to almost three thousand years later, until the fall of the Tang dynasty in the tenth century. They reveal rich, multicultural, yet recognizably interlinked civilizations across hundreds of miles and years.

But the most powerful and incontrovertible evidence that this area was once the habitat of Europoid peoples springs from their mummies. Preserved by extreme aridity and saline sands, those buried in winter were protected by bitter cold against the bacteria that would ordinarily have consumed them. Aside from the evidence of their origins provided by DNA, their physical appearance is almost shockingly Western. Their homelands deep within Xinjiang are now claimed and occupied by the Chinese, who reconquered the precariously independent province in the mid-twentieth century; but their genetic heritage, it seems, passed to the Muslim Uighurs, who arrived here in the ninth century and whose separatists hail the mummies as their ancestors.

The politicizing of mummies follows that of archaeology itself, but it has been transformed by DNA analysis and an increased stress on ethnic rather than cultural or linguistic identity. In Russia the tattooed mummies of Pazyryk in southwest Siberia and the “Ice Princess” of the Altai near the Chinese border, preserved by frozen rainwater, have provoked an old tension between advocates of Mongoloid and Caucasoid loyalties. In Xinjiang the number of mummies discovered—and their widely separate dates—are still more fraught. Over a dozen sites have yielded more than five hundred mummies, many of them finely preserved. Thousands more have been scattered over the sands by scavenging villagers and salt-diggers.

Advertisement

Visitors to the Uighur regional museum in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, are astonished to find some of these mummies resting in glass vitrines as if asleep. A red-haired, hook-nosed chieftain lies askew in leggings of scarlet and eggshell blue. Near him “the Beauty of Loulan,” a four-thousand-year-old brunette whose face still shows the scaffolding of regular beauty, has been adopted by Uighur loyalists as the mother of their people.

At the University of Pennsylvania Museum three mummies went briefly on display, and it was these—on their first journey to North America—that lay at the exhibition’s heart. The first, “Yingpan Man,” was in fact a brilliant suit of clothes in which the corpse had grown so fragile that it had been retained in China. Dated to the fifth century AD, the cadaver was comparatively recent: perhaps a Sogdian, one of an Iranian people whose merchants dominated the contemporary Silk Road. He was almost 6'6" tall on excavation, fair-haired, and buried with a Roman glass bowl. His white death mask is still banded in gold and shows a trickle of painted mustache. But most remarkable is the burgundy caftan that clothes him. It is woven with bands of goats and bulls—Persian motifs—and with Greco-Roman putti brandishing gladiatorial shields and spears.

The second mummy on display was a tiny baby from the eighth century BC, its sex unknown. It was accompanied by a nursing bottle made from a goat’s udder. Its eyebrows are blond, and wisps of pale hair escape its snugly superimposed blue and red bonnets. The blue stones covering its eyes may—according to the museum commentary—have reproduced their iris color.

But the centerpiece of the exhibition is a spectacular reproduction of Xiaohe, the region’s oldest cemetery, which lies some hundred miles west of China’s remote nuclear testing site at Lop Nor. Its wooden graves, shaped like upended boats, foundered long ago into the encroaching sands of the Taklamakan Desert in southern Xinjiang. The cemetery dates back nearly four thousand years, perhaps to 1800 BC—a millennium older than the fair-haired baby. Its graves are still staked enigmatically with wooden phalli (for the women) and vulvas (for the men), and the saline soil has preserved some of its mummies like sleeping statues.

Most notable among these is the so-called “Beauty of Xiaohe,” whose dried cadaver was the still heart of the museum exhibition (see illustration on page 17). She was a Caucasoid woman in her early forties at death, slim, and rather tall for her time—5'2" perhaps—with petite features and a mass of reddish hair. Unlike “the Beauty of Loulan,” whose face has blackened to ebony, her whole body had been covered in white unguent, so that she seems retracted palely into sleep. Even her eyelashes are intact, and a glint of teeth shows between faintly parted lips. Shrouded in a tasseled woolen cloak, she wears fur-lined boots and a feathered felt hat, and was buried with pouches of medicinal or ritual herbs. A nearby basket of wheat betrays that her people were not only herders but agriculturalists.

From time to time these female mummies seduce scholars into nostalgic eulogies, as if a posthumous beauty contest were taking place. (A Chinese archaeologist all but fell in love with one.) But they are both more and less than they seem. The lungs of “the Beauty of Loulan” were found to be lined with charcoal dust, lice infested her eyelashes, and the Xiaohe beauty’s hair held the casings of maggots.

Both women must have belonged to the vanguard of settlers in the region, and are eloquent evidence of its colonization by groups already strong in their own culture. And it is through cultural transmission that the exhibition hints at its grandest claim: that these forgotten peoples are the missing link between East and West, perhaps responsible for such crucial introductions to China as the working of bronze, the cultivation of wheat (started in Anatolia in 8000 BC), the domestication of sheep, and even the use of the wheel.

Recent DNA analysis of mummies at Xiaohe cemetery suggests a lineage reaching back to the Siberian steppe and the fringes of Europe. But today’s Uighur natives originated elsewhere. A Turkic people, they arrived from Mongolia in the ninth century and apparently absorbed the earlier inhabitants. Anyone traveling the remote southern Silk Road today may be startled by the sight of auburn hair and blue or green eyes gazing out from near-European features. Yet despite DNA proof of a partly Western lineage, the same tests, paradoxically, relate the Uighur only uncertainly to the mummies.

Advertisement

Uighur anger against the incoming Chinese, who threaten to outnumber them in their own province, has periodically led to bloody conflict, most recently in July 2009, when at least two hundred people died. And their adoption of the region’s first inhabitants, of course, is a tacit declaration of their own primacy. “The Beauty of Loulan” is both their emblem and their birth certificate.

Was the Chinese withdrawal of their exhibits from the University of Pennsylvania Museum an offshoot of this rankling political conflict? The mummies’ Caucasoid origins are commonly accepted now, and they had already been shown for four months at the Bowers Museum in California, which first negotiated their release from China, and then at the Houston Museum of Natural Science between late August and early January.

Professor Victor Mair of the University of Pennsylvania, who more than anyone is responsible for bringing the mummies of Xinjiang to world attention, perceives the exhibition—he has edited its catalog—as rigorously apolitical. Instead, he feels, it is filling a yawning gap in world knowledge. Yet it was only in Pennsylvania that Chinese alarm (or perhaps annoyance) surfaced. A week and a half before the exhibition’s opening the Beijing authorities demanded that the crates from Houston remain unopened and be returned to China, stating that the mummies had been away too long.

In the often factionalized world of Chinese politics, the regional authorities in Xinjiang, it seems, were in favor of the exhibition, but mid-level bureaucrats in Beijing were not. And these obstructors in the State Administration of Cultural Heritage clearly enjoyed higher backing. The University of Pennsylvania Museum immediately sought the support of the Chinese ambassador in Washington and of Jon Huntsman, the US ambassador in Beijing. Then the Chinese foreign minister became involved, and an uneasy compromise was reached. The mummies had their brief showing in Pennsylvania—they were on display for less than four weeks—and the artifacts remained for two weeks more.

The Bowers Museum at Santa Ana, which first selected the exhibits, struck an unusually cordial deal with the Chinese. But by the time the exhibits reached Pennsylvania this intimacy no longer held good. Perhaps the international reach of the University of Pennsylvania Museum, and the scholars associated with it, were politically unnerving to Beijing. In the exhibition catalog the art historian Lothar von Falkenhausen writes that “the present exhibition, for reasons connected with the historical situation of Xinjiang today, particularly emphasizes the Chinese cultural impact on the ‘Western Regions.'” But the setting in which the museum places the artifacts scarcely supports such a reading. And there may be yet another explanation.

Among the glories of the museum’s own collection is a pair of seventh- century limestone bas-reliefs. They depict two of the six warhorses of the warrior-emperor Taizong, who rode them into battle at the height of the Tang empire. Each horse had its own history of endurance. The sculptures even now show the shadowy arrows that wounded them. On the emperor’s death the reliefs of these six chargers were erected by his tomb, and their spirits were worshiped there alongside his for another thousand years.

Four of these panels survive in China’s Beilin Museum in Xian. The other two, in the disruptive period of China’s civil war, found their way to the United States. But in the words of the University of Pennsylvania Museum plaque, the horses “continue to hold a special place in the hearts of the Chinese to this day.” They have been lauded in China as patriotic symbols—they have even appeared on postage stamps—reflecting as they do the farthest reaches of Chinese power.

From time to time these massive reliefs—they have been called China’s Elgin Marbles—have been requested for exhibition by Beijing. But the University of Pennsylvania Museum has never acceded, knowing how hard it would be for China to return them. For this—the speculation runs—the museum is being obliquely punished.

However this may be, the exhibition—even in its present, shadowy state—continues to propagate its larger vision. A bold time line still stretches for some thirty feet over the wall that first greets visitors. The expansion of Indo-Europeans east and west from their homeland by the Black Sea in the fourth millennium BC, the domestication of the horse on the Russian steppe around 3200 BC, and the invention of chariots on these same steppes almost a millennium afterward place in grand perspective such later events as the foundation of Rome or of Xian. And into this dizzy trajectory fall the dates 1800–1500 BC, when the Xiaohe cemetery—most splendid of the museum’s reconstructions—was “created by unknown people.”

This Issue

May 12, 2011