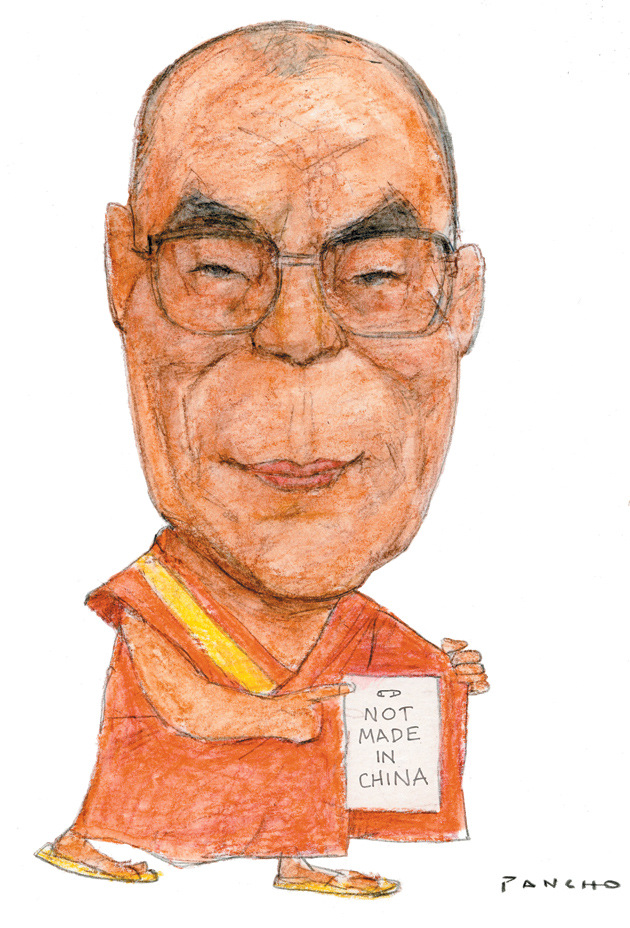

On March 10 the Fourteenth Dalai Lama made front-page news throughout the world by saying,

As early as the 1960s, I have repeatedly stressed that Tibetans need a leader, elected freely by the Tibetan people, to whom I can devolve power. Now, we have clearly reached the time to put this into effect. During the forthcoming eleventh session of the fourteenth Tibetan Parliament in Exile, which begins on 14th March, I will formally propose that the necessary amendments be made to the Charter for Tibetans in Exile, reflecting my decision to devolve my formal authority to the elected leader.

It is well known that Beijing regularly dismisses the Dalai Lama as a criminal and a “splittist.” But will this announcement that he will relinquish his temporal leadership make it more likely that Tibet will become a truly autonomous part of China, as the Dalai Lama has for years proposed to Beijing?1

As the title of his new book suggests, Tim Johnson thinks that there is no chance of such an arrangement. On the final page he concludes:

As the Dalai Lama’s life enters its final stretch…more and more Han [ethnic Chinese] migrants will arrive on the Tibetan plateau, and almost inevitably Tibet will head the way of Inner Mongolia and other regions of the mainland subsumed by the vast Han majority. The race is nearly over.

The Mongolian comparison is especially grim: in 1949, Mongols in their region outnumbered Hans by five to one. By the year 2000 there had been so much Han migration that there were 4.6 Hans for every Mongol in Inner Mongolia, and now only 17 percent of its population are Mongols, “confined largely to nomadic settlements and ethnic oases in a larger sea of Han.”

This is not what admirers of the Dalai Lama want to hear, and I feel uneasy endorsing it; but from my first visit to Tibet in 1982 I noticed how the Hans were swamping almost every aspect of Tibetan life. Johnson writes that during their annual negotiations in China, the Dalai Lama’s emissaries’ proposal of an autonomous Tibet within the People’s Republic, with its own religious, educational, and other cultural characteristics, has been dismissed by the regime; the Chinese side has insisted that only the “criminal, splittist Dalai” is discussable. In his book To a Mountain in Tibet, Colin Thubron writes tersely, but characteristically to the point, of the Dalai Lama:

His apostleship of peace has brought his country a refracted holiness, but no Chinese concession. The West fetes and wonders at him. As for China, his distrust of material institutions, even of his own office, renders him all but incomprehensible.2

More than incomprehensible: Beijing calls the Dalai Lama “a wolf wrapped in robes, a monster with a human face and an animal’s heart.” I have heard young Chinese studying in British universities like Oxford and the LSE quote Rupert Murdoch, who called the Dalai Lama “a very political old monk shuffling around in Gucci shoes.” Murdoch, ever keen to flatter the Chinese in order to get access to their markets, could be expected to make cheap remarks about the far more intelligent and brave Tibetan.

Tim Johnson spent six years in Beijing as a bureau chief for the Knight-Ridder and McClatchy newspapers, and he identifies China’s three greatest hates: “the three Ts and one F—meaning Taiwan, Tibet, and the Tiananmen Square pro-democracy movement;…the F refers to the Falun Gong meditation sect…harshly suppressed and declared an ‘evil cult.'” Of these, Tibet is the most “radioactive”; Johnson was briefly there in 2008, although it was off-limits to journalists, as it had been for at least thirty years. He buttresses, and occasionally pads out, his pessimistic case (which is basically an informed guess) by going to India, Tibet, areas of China sometimes called Greater Tibet in which many Tibetans live, Inner Mongolia, and Xinjiang, home of the oppressed Muslim Uighurs.

Born in 1935, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama knows the looming succession is a serious matter. Two years ago he told me that his doctors had assured him he would live to 102, thus probably outlasting the Chinese Communists,3 and, probably joking, he told Johnson that he doubted the Communist regime would last another ten years. From time to time he has said he would like to reappear as a “humble monk,” but he has said, too, that “if my death comes when we are still in a refugee status, then logically my reincarnation will come outside Tibet.” It is also ritually legitimate, as Johnson observes, for a living Dalai Lama to identify his next incarnation.

But Beijing has already rehearsed for what comes after this Dalai Lama. In 1989 the Tenth Panchen Lama, Tibet’s second-highest religious figure, died, and in 1995, the Dalai Lama designated as his incarnation a boy called Gedhun Choekyi Nyima. This child was almost immediately kidnapped with his family and replaced by a Communist-approved boy as the authentic Eleventh Panchen; most Tibetans reject him, Johnson notes, as a “faux Panchen Lama.”

Advertisement

In Beijing Johnson interviewed Yabshi Pan Rinzinwangmo, or Renji, the Tenth Panchen’s daughter by a Chinese woman. A carefully protected woman who is sometimes called “Princess,” Renji remembers her father; when she was six she and her mother flew to Tibet where the Panchen had mysteriously died. As I found when she visited me in London, she is cautious about committing herself on China’s role in Tibet or on the Eleventh incarnation. “With me,” Johnson writes,

she kept her guard shrewdly, saying only that she has yet to gaze into his [the Eleventh Panchen’s] eyes [to recognize—or not—her father’s spirit]…. She understands her strategic value in the drama over the young man who now wears the yellow hat of the Panchen Lama: “He needs me more than I need him.”

Discreet though she is, Renji must know that statement will panic the Chinese authorities. Even more alarming, in 2003 she said this to me: “What do you think is my relationship to the boy in Beijing? Shouldn’t he respect me because of my father?”4

During these disputes about incarnations, the Dalai Lama tends to put first on his list of preferred successors the Seventeenth Karmapa, the leader, now in his twenties, of another Buddhist lineage, who escaped from China in 1999 and now lives near Dharamsala, the Dalai Lama’s Indian sanctuary. In the minds of many Tibetans he has taken the place of the Panchen as their favored successor to the Dalai Lama. Energetically pursuing his story, Johnson traveled to see the Karmapa. He is unique in that both Beijing and the Dalai Lama look upon him favorably, at least, says Johnson, as “a temporary leader, or regent…a pan-Tibetan figure above sectarian disputes.”

Recently, the Karmapa has been embroiled in an Indian media farce that accused him of taking huge sums of money from various sources including China. This has largely blown over.5 As discreet as the Panchen Lama’s daughter, he told Johnson:

I’m already the Karmapa. That’s my role and it’s already one I feel quite weighed down by…. For anywhere between 800 and 900 years, the Karmapa has been a very apolitical figure, a person who has concentrated on spiritual leadership, not involved in any way with governmental leadership. So I think it would be very difficult to change that historical pattern overnight and turn the role of the Karmapa into something more than strictly a spiritual teacher.

The Karmapa is aware that “the situation of Tibet is dire…. So it’s actually quite a hot potato that we have here…. If we were to wait 50 years, we would be in danger of losing a great chunk of Tibetan culture that could not be recovered.”

Another of Johnson’s sources is Tsering Woeser, a prominent Tibetan dissident, poet, and blogger who lives in Beijing with her Chinese husband, Wang Lixiong, a famous novelist and supporter of the Tibetan cause. A bird in a gilded cage, Woeser is in exile from Tibet and forbidden to leave China. Although her mother, sister, and brother still live in Tibet, Woeser is less discreet than Renji or the Karmapa:

I am pessimistic…. Tibet is totally controlled by the Chinese government. Under these circumstances, it’s impossible for Tibetans to change the destiny of Tibet. Tibet can only change along with China. However, the Chinese government is a rather despotic dictatorship so the possibility of change in Tibet is quite low…. The future of Tibet will not be promising…. The damage is accelerating.

This damage can take surprising forms. In Nepal, Johnson met a young Tibetan with frostbitten toes from his agonizing trek across the mountains. Why had he fled? He didn’t get along with his older brother. Truly amazingly, when asked if he longed, as most such refugees passionately insist, to meet the Dalai Lama in India, the young man said. “I’ve never heard of the Dalai Lama.” Some may suppose his village was extremely remote, but in my own travels through Tibet I never met a single Tibetan, no matter how far from the cities, who didn’t worship the Dalai Lama. That was twenty years ago. Chinese domination may be more pervasive than we suppose.

Johnson’s experiences in Tibet were brief but while there he kept his eyes and ears open. It is well known, for example, that up to 1.8 million herdsmen and nomads are being moved off the grasslands into semi-urban housing. Beijing, Johnson observes, claims that overgrazing was keeping the nomads poor, and that relocating them is necessary to restore the environment. Johnson saw “vast stretches of overgrazed grasslands…desert-like areas that barely sustain life.” He contends, however, that shifting the herders off their traditional terrain is ending a traditional way of life, “a pillar of Tibetan identity.” The bleak camps in which they are crammed “facilitate Chinese surveillance and control of the nomads, most of whom hold little allegiance to China.” Nor is it only the nomads whom Beijing squeezes. Monks and nuns, writes Johnson, who refuse to denounce the Dalai Lama are given sentences of five years; in late 2009, a US Congress–sponsored commission “tallied 445 monks and nuns in prison on political charges.”

Advertisement

Lhasa, Johnson found, “has lost some of its soul…. Tibetans were a minority. Han migrants drive nearly every taxi, and Han and ethnic Hui Muslims own most shops, a sign of the marginalization of Tibetans.” This is precisely what Colin Thubron noticed, far from Lhasa on the Chinese–Nepali border, in the first Tibetan town he entered. A US State Department study estimates—how was this counted?—that there are “ten thousand sex workers” in the two main Tibetan cities, Lhasa and Shigatse: “some of the prostitution occurred at sites owned by the CCP [Chinese Communist Party], the government, and the military.”

And far from Tibet, as Johnson points out, Beijing threatens ill-defined consequences for any country that assents to official contact with the Dalai Lama. These threats work. In 2008 British Foreign Secretary David Milliband, after years of national silence on the subject, suddenly declared that Tibet was a part of China. Also in 2008, then–prime minister Gordon Brown greeted the Dalai Lama at the Archbishop of Canterbury’s official residence, Lambeth Palace, rather than at 10 Downing Street, thus appearing to regard the Dalai Lama as a religious, not a political, leader; Tibetans regard him as both. Russia and South Korea refuse visits from the Dalai Lama, while successive American presidents since Clinton, all of whom professed to admire the Tibetan leader, avoided greeting him in the Oval Office—as has President Obama—and contrived to have him “drop by” in less formal quarters in the White House.

Johnson mentions Wal-Mart, “the world’s biggest retailer…[which] imports about 70 percent of its products from China,” and perceives what he calls the “Wal-Mart fissure” into which Tibet might fall. The concerns of huge employers like Wal-Mart, he contends, have far more influence on US China policy, and therefore on Tibet, than any number of pro-Tibet Hollywood stars and what he sees as the ineffectual Tibetan government in exile. “Dharamsala has none of the revolutionary zeal of Ramallah in the West Bank, nor does it simmer with the anti-Castro–type conspiracies that roil the Miami of Cuban-Americans.” The readiness to use violence on the West Bank or the roiling conspiracies in Miami seem to me less admirable than the patient Tibetan exile government and its capable representatives abroad.

But the Chinese never let up their pressure on Tibetan matters. In 2009, Johnson says, legislators in California sponsored a resolution to establish “Dalai Lama and Tibet Awareness Day”; before long Beijing’s lobbying, involving threats of economic sanctions, persuaded a majority in the legislature to slide the resolution into limbo. A year later Beijing bullied nineteen countries into boycotting the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo in Oslo. American policymakers are transfixed by Beijing’s huge holdings of US Treasury bonds. Bullying gets ever more effective as Washington and its allies count on Beijing to help negotiate with North Korea, Iran, and perhaps Burma. Under such battering, Tibet fades into the background.

Johnson has asked himself why Beijing doesn’t offer Tibet the same deal that it concluded with Hong Kong: “One country, two systems.” But then, he admits, “I came to my senses. The Communist Party would cede no ground.” Johnson notes that whenever the Dalai Lama’s negotiators put forward proposals for a measure of Tibetan autonomy, Beijing’s reply is that such suggestions are “exactly the same as ‘semi-independence’ and ‘covert independence.'” Other ethnic nationalists, Beijing fears, would feel a spurt of hope. Tibet’s vital minerals and water resources could be lost. Missile bases might have to be withdrawn. Indeed, “most Chinese I knew,” Johnson says, “wanted to pull Tibet more tightly into Beijing’s embrace rather than let up on a bear hug many Tibetans see as suffocating.” He might have added, “How many battalions does the Dalai Lama have?” And what if Communist China collapsed? Other oppressive regimes have perished in recent memory, although in the case of the former Soviet Union the conflicts with some of the ethnic areas—dating back at least as far as Tolstoy—remain long-lasting and deadly.

The pressure on Beijing may well lessen after the Dalai Lama dies. When the Tibetan exile government discusses matters like a democratically elected government and a new prime minister, with the Dalai Lama deliberately absenting himself, it is apparent they are not much interested in a future without the Dalai Lama in charge. In India Johnson met Tenzin Tsundue, one of the leaders of an exile faction of young Tibetans demanding full independence for Tibet. In 2002, when then Chinese premier Zhu Rongji was visiting Bombay, Tsundue scaled a tall building to unfurl a banner saying “Free Tibet.” But even this daring activist admitted to Johnson that many Tibetans in the diaspora wait for indications from the Dalai Lama before they act. “The people worship His Holiness as the Buddha. He’s a Buddha in real life. People say [to him], ‘I will die if you say. You make the decision and I will follow.'” When the parliament in exile recently considered the constitutional change that would lead to a replacement for the Dalai Lama, eleven of the first fourteen members to speak opposed any move that would permit such a change.

Some Tibetans look farther into the future. It surprised Johnson to learn about the Special Frontier Force (SFF) of Tibetan mountain commandos created in India after the 1962 border war between China and India. In a new war, it was imagined, these commandos could fight in the Chinese rear. More interesting still is that this unit is under the command not of the army but of the Indian intelligence agency. It is not well known that several thousand young Tibetans have been trained this way, Johnson writes, who “see their service as keeping hopes for Tibetan independence alive.” Those in the Vikasregiment of the SFF sing:

We are the Vikasi

The Chinese snatched Tibet from us

And kicked us out from our home….

One day, surely one day

We will teach the Chinese a lesson….

The Dalai Lama “bristled” when Johnson mentioned armed resistance. “Our struggle is not military. It is not realistic. It’s suicidal. It’s a waste of human life.”

The illusions of Tibetans and their supporters abroad worry Johnson. He emphasizes that “no matter how worried party leaders may be about Tibet, their public posture reflects no indecision or internal debate.” The outrage of Hollywood stars like Richard Gere has not weakened the tightening Chinese grip on the region. Beijing is on a roll that is hard for anyone to resist including the great powers, much less a few million, usually nonviolent, Tibetans. Johnson warns that Tibetans hoping to outlast the present Beijing regime, gaining hope when they hear that the Dalai Lama has met President Obama or that international street actions and campaigns support Tibet, are doomed to disappointment. “I rarely had the heart to disrupt their delusional dreams.”

On the other hand Chinese leaders react with satisfaction when they hear men like David Milliband state that Tibet belongs to China. It makes no difference in Beijing if those who make such statements believe what they are saying. Words mean everything to the Communist Party, which equates them with acts; that is why they lock up dissidents like Liu Xiaobo—and Johnson knows him well—because of what they have said. And because words mean so much the Chinese “have ensured that he [the Dalai Lama] has almost no way of communicating with ordinary Chinese,” much less Tibetans.6

The Dalai Lama could not be more of a realist: “The crucial question is whether Tibet will become like Inner Mongolia, where Mongols have now become a minority. When that happens the significance of self-rule is lost.” Each year his death draws closer and the world may be faced with the spectacle of what Tim Johnson, in his energetically researched and comprehensive book, calls “dueling Dalai Lamas.” One, beyond Beijing’s grasp, might be a woman, His Holiness has suggested, or, in accordance with traditional ritual, he could identify a reincarnation before his death. The rival Dalai Lama would be like Beijing’s tame Eleventh Panchen, scorned in Tibet, and into whose eyes Renji, the young woman who the Communist Party claims is this faux incarnation’s spiritual daughter, has yet to gaze.

This Issue

May 26, 2011

-

1

According to Robert Barnett, an authority on Tibet at Columbia, “It is true that for China and for most of us, we will not see much difference in the short term if his plan goes ahead. The Dalai Lama has said that he will continue travelling around the world as a religious leader and will still speak on Tibetan issues, albeit in a personal capacity. So this is not a monastic vow of silence or an end to his role as the figurehead of the Tibetan people and as the most powerful voice through which their concerns will be expressed.” See Barnett, “Viewpoint: Dalai Lama’s Exile Challenge for Tibetans,” bbc.co.uk, March 14, 2011. ↩

-

2

Harper, 2011, p. 109; reviewed in these pages by Pico Iyer, April 7, 2011. ↩

-

3

See my “How He Sees It Now,” The New York Review, July 17, 2008. ↩

-

4

Johnson writes that there is some sort of special relationship between President Hu Jintao and Renji because he respected the Tenth Panchen when he was alive. But in 1989 when I met Hu in Tibet, where he was Party secretary, he told me he despised Tibetans. ↩

-

5

For a sensible round-up of this story see Paul Mooney, “Many Accusations but Few Facts as Karmapa Accused of Spying,” South China Morning Post, February 9, 2011. ↩

-

6

An exception was the Internet conversation last year between the Dalai Lama and some Chinese, which Johnson describes in his book. See also Perry Link, “Talking About Tibet: An Open Dialogue Between Chinese Citizens and the Dalai Lama,” NYRblog, May 24, 2010. ↩