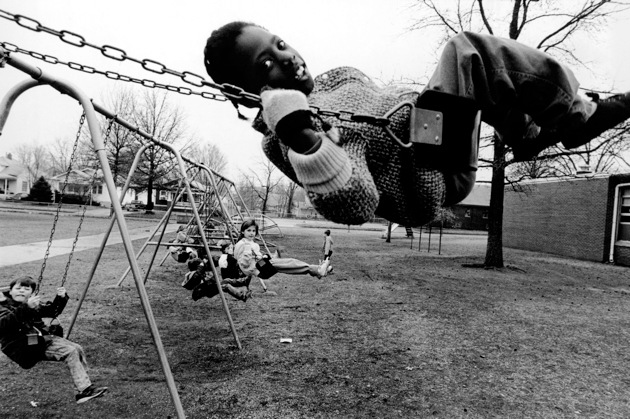

It is a well-known fact that American education is in crisis. Black and Hispanic children have lower test scores than white and Asian children. The performance of American students on international tests is mediocre.

Less well known are contrary facts. The black–white achievement gap, as a recent report put it, “is as old as the nation itself.” It was cut in half in the 1970s and 1980s, probably by desegregation, increased economic opportunities for black families, federal investment in early childhood education, and reductions in class size.1

Another little-known fact is that American students have never performed well on international tests. When the first such tests were given in the mid-1960s, our students usually scored at or below the median, and sometimes at the bottom of the pack. This mediocre performance is nothing to boast about, but it is not an indicator of future economic decline. Despite our students’ mediocre test scores, the nation’s economy has been robust for most of the past half-century. And the news is not all terrible. On the latest international test, the Program for International Student Assessment, American schools in which fewer than 10 percent of the students were poor outperformed the schools of Finland, Japan, and Korea. Even when as many as 25 percent of the students were poor, American schools performed as well as the top-scoring nations. As the proportion of poor students rises, the scores of US schools drop.2

To put the current “crisis” into perspective, it is well to recall that American education was in crisis a century ago, when urban schools were overcrowded, swamped with students from Eastern and Southern Europe who didn’t speak English. The popular press at that time warned that the nation was being overrun by a human tide from inferior cultures, and the very survival of our nation was supposedly at risk.

Then there was the crisis of the 1950s: influential authors such as Rudolf Flesch and Arthur Bestor bemoaned the sorry state of the schools in the early 1950s, and other critics such as Admiral Hyman Rickover blamed them when the Soviets launched Sputnik into orbit in 1957. Since then, the schools have been in nearly constant crisis. In the 1960s, civil rights leaders condemned the public schools for institutionalized racism. In the 1970s, critics like Charles Silberman discerned a “crisis in the classroom” and flayed the schools for “mindlessness.” In 1983, a national commission convened by US Secretary of Education Terrell Bell declared that “a rising tide of mediocrity” in the public schools put the nation at risk. In 1989, President George H.W. Bush convened the nation’s governors to agree on national goals for education. Since then, political leaders have agreed that what is needed to improve education is greater accountability, based on standardized tests.

A decade ago, President George W. Bush satisfied the demand for testing and accountability by proposing the legislation now known as No Child Left Behind (NCLB), passed by Congress in 2001 and signed into law by President Bush in January 2002. It mandated that every public school in the nation must test all children in reading and mathematics from grades three through eight and classify the scores by racial and ethnic groups (white, African- American, Latino, Asian-American, Native American, etc.), low-income students, students with disabilities, and students with limited English skills. By 2014, every student in every category was expected to reach proficiency in those subjects, as defined by each state and measured by standardized tests selected by each state, or the school would face a series of escalating sanctions, culminating in firing part or all of the staff, closing the school, or handing control of the school over to the state or to private management.

Because of its utopian goals, coupled with harsh sanctions, NCLB has turned out to be the worst federal education legislation ever passed. Recently, Secretary of Education Arne Duncan predicted that more than 80 percent of the nation’s public schools would be labeled “failing” this year by federal standards, including some excellent schools in which students (usually those with disabilities) were not on track to meet the target. By 2014, if the law is unchanged, very few public schools will not be labeled “failures.” No nation has ever achieved 100 percent proficiency for all its students, and no state in this nation is anywhere close to achieving it. No nation has ever passed a law that would result in stigmatizing almost every one of its schools. The Bush-era law is a public policy disaster of epic proportions, yet Congress has been unable to reach consensus about changing it.

The Obama administration has offered to grant waivers from the onerous sanctions of NCLB, but only to states willing to adopt its preferred remedies: privately managed charter schools, evaluations of teachers on the basis of their students’ test scores, acceptance of a recently developed set of national standards in reading and mathematics, and agreement to fire the staff and close the schools that have persistently low scores. None of the Obama administration’s favored reforms—remarkably similar to those of the Bush administration—is supported by experience or evidence.

Advertisement

Most research studies agree that charter schools are, on average, no more successful than regular public schools; that evaluating teachers on the basis of their students’ test scores is fraught with inaccuracy and promotes narrowing of the curriculum to only the subjects tested, encouraging some districts to drop the arts or other nontested subjects; and that the strategy of closing schools disrupts communities without necessarily producing better schools. In addition, the “Common Core State Standards” in reading and mathematics that states must adopt if they hope to receive a waiver from the US Department of Education have never been subjected to field-testing.

So, yes, there is a crisis in education, a crisis caused by ill-considered federal legislation that sets utopian targets and then punishes schools and educators when they cannot meet impossible goals. As a result, cheating scandals have been discovered in Washington, D.C., Atlanta, Baltimore, Pennsylvania, and elsewhere. Some people do terrible things when faced with unreasonable targets and draconian punishment.

The response to the current crisis in education tends to reflect two different worldviews. On one side are those who call themselves “reformers.” The reformers believe that the schools can be improved by more testing, more punishment of educators (also known as “accountability”), more charter schools, and strict adherence to free-market principles in relation to employees (teachers) and consumers (students). On the other are those who reject the reformers’ proposals and emphasize the importance of addressing the social conditions—especially poverty—that are the root causes of poor academic achievement. Many of these people—often parents in the public school system, experienced teachers, and scholars of education—favor changes based on improving curriculum, facilities, and materials, improving teacher recruitment and preparation, and attending to the cognitive, social, and emotional development of children. The critics of test-based accountability and free-market policies do not have a name, so the reformers call them “anti-reform.” It might be better to describe them as defenders of common sense and sound education.

Steven Brill’s Class Warfare: Inside the Fight to Fix America’s Schools celebrates the improbable consensus among conservative Republicans, major foundations, Wall Street financiers, and the Obama administration about school reform. Brill, a journalist and entrepreneur, portrays the leaders of today’s reform movement as heroes. They include Wendy Kopp, who created Teach for America (TFA) and raised some $500 million for the organization over the past decade; Jonathan Schnur, whom he credits as the architect of the Obama administration’s $4.35 billion competition called Race to the Top; Michelle Rhee, chancellor of schools in the District of Columbia from 2007 to 2010; Joel Klein, chancellor of the New York City public schools from 2002 to 2010 and now chief adviser to Rupert Murdoch; Eva Moskowitz, leader of the Harlem Success Academy charter school chain; and David Levin and Michael Feinberg, founders of the KIPP charter schools.

Brill also lavishly praises the billionaire equity investors and hedge fund managers who have financed the reform movement, including Whitney Tilson, Ravenel Boykin Curry IV, John Petry, and Joel Greenblatt. Brill writes reverentially about their glamorous world. Curry, for example,

seems the typical preppy socialite. He and his wife have homes in Manhattan (Central Park South), East Hampton, and the Dominican Republic. His father, Ravenel Curry III, also runs a money fund. He and his wife frequently appear in society columns, and she’s a well-known high-end interior decorator.

A graduate of Yale and the Harvard Business School, Curry is deeply involved in school reform.

The financiers of public school reform described here live in a world of spectacular wealth. They believe in measurable outcomes; their faith in test scores is greater than that of most educators, who understand that standardized tests are not scientific instruments and that scores on the tests represent only a small part of what schools are expected to accomplish. The Wall Street men have found a cause that is both “exciting and fun” and, as Curry IV puts it, “because so many of us got interested in this at the same time, you get to work with people who are your friends.” It is unlikely that any of them have close personal connections to public education, yet they have made it their mission to change national education policy. School reform is their favorite cause, and they like to think of themselves as leaders in the civil rights movement of their day, something unusual for men of their wealth and social status.

Advertisement

In 2005, the financiers formed an organization called Democrats for Education Reform (DFER) to promote ideas such as choice and accountability that were traditionally associated with the Republican Party. They set out to change Democratic Party policy, which in the past, as they saw it, was in thrall to the teachers’ unions and was committed to programs that funneled federal money by formula to the poorest children. DFER used its bountiful resources to underwrite a different agenda, one that was not beholden to the unions and that relied on competition, not equity.

While it was easy for the Wall Street tycoons to finance charter schools like KIPP and entrepreneurial ventures like Teach for America, what really excited them was using their money to alter the politics of education. The best way to leverage their investments, Brill tells us, was to identify and fund key Democrats who would share their agenda. One of them was a new senator from Illinois named Barack Obama, who helped launch DFER at its opening event on June 3, 2005. The evening began with a small dinner at the elegant Café Gray in the Time Warner Center in New York City, then moved to Curry’s nearby apartment on Central Park South, where an overflow crowd of 150 had gathered.

DFER also befriended Congressman George Miller from California, the powerful leader of the Democrats on the House Education and Labor Committee. DFER supported Cory Booker, who eventually became mayor of Newark. A DFER fund-raiser produced $45,000 for Congressman James Clyburn, “the most influential member of the Congressional Black Caucus,” who returned home to South Carolina to champion tuition tax credits and charter schools. Brill writes that DFER sent a memo to the Obama team immediately after the presidential election, naming its choice for each position. At the top of its list, for secretary of education, was Arne Duncan.

In Brill’s telling, anyone who opposes DFER’s definition of school reform is a defender of the status quo or a tool of the unions. He disparages the eminent scholar Linda Darling-Hammond of Stanford University, because she criticized Teach for America. Darling-Hammond believes that future teachers should have a deep grounding in the professional skills needed to teach children who require special attention, such as those who are new immigrants, those who have disabilities, and others who have marked difficulties in learning; she also believes that future teachers should be committed to teaching as a career, not short-term charity work. Yet Brill derides her views because higher standards for entry into the teaching profession would surely exclude TFA recruits, who receive a mere five weeks of training before they become full-time teachers in some of the nation’s most challenging schools. As a critic of the current reform agenda, I too am one of his targets; I will deal with the false allegations he makes in a different forum.

Brill believes that teachers are the primary reason for students’ failure or success. If students have great teachers, their test scores in reading and math will soar. If they don’t, it is their teachers’ fault. Reduce the power of the unions, he argues, and bad teachers could be quickly dismissed. Of course, bad teachers should be dismissed, and many are. Fifty percent of those who begin teaching are gone within five years. But once teachers have been awarded tenure by their principal, they have the right to a hearing before they can be fired. If hearings go on for years, the district leadership should be held accountable.

Unfortunately, Brill is completely ignorant of a vast body of research literature about teaching. Economists agree that teachers are the most important influence on student test scores inside the school, but the influence of schools and teachers is dwarfed by nonschool factors, most especially by family income. The reformers like to say that poverty doesn’t make a difference, but they are wrong. Poverty matters. The achievement gap between children of affluence and children of poverty starts long before the first day of school. It reflects the nutrition and medical care available to pregnant women and their children, as well as the educational level of the children’s parents, the vocabulary they hear, and the experiences to which they are exposed.

Poor children can learn and excel, but the odds are against them. Reformers like to say that “demography is not destiny,” but saying so doesn’t make it true: demography is powerful. Every testing program shows a tight correlation between family income and test scores, whether it is the SAT, the ACT, the federal testing program, or state tests.

Brill seems unaware of these findings. He expresses enthusiasm for tying teachers’ evaluations—which determine whether they will be fired—to their students’ test scores, but the weight of research evidence is against him. He often cherry-picks a single study or recounts an anecdote to support his views, but is apparently ignorant of the many studies that qualify or contradict what he believes. Studies of teacher effectiveness agree that there are wide variations in the quality of teaching, but they don’t agree on a mechanical formula to identify which teachers are more or less effective. Ultimately, that judgment must be made by experienced supervisors who frequently observe the teachers’ performance.

Brill argues that American schools have been crippled by the power of the teachers’ unions. If only they could be neutralized, then principals could fire those who are incompetent or fail to raise test scores. Freed of the shackles imposed by the unions, the schools would dramatically improve their performance. He never explains why schools in non-union states fare poorly or have only middling records on federal tests, or why heavily unionized states—Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Jersey—are at the top. Charter schools are typically non-union, yet their performance on average is no better than that of regular public schools. Brill never has to confront that fact because he doesn’t acknowledge the wide variation in quality among our nation’s more than five thousand charter schools, or the studies showing that many charters have disproportionately small enrollments of children with special needs and children whose English is limited.

Somewhat incoherently, Brill ends by arguing that deep reform depends on unions joining the battle, not as adversaries but as collaborators with those who support privatization and deprofessionalization of teaching. He proposes that Mayor Michael Bloomberg should appoint Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, as chancellor of the New York City public schools. He suggests that unions should join the reform movement even if they disagree with it, because it is so powerful. The difficulty with his argument here is that he seems unaware of or indifferent to the actual record of what he says is a movement for reform. He overlooks some of the movement’s biggest embarrassments, such as the test score scandal in Washington, D.C., which tarnished Michelle Rhee’s tenure, and the collapse of New York City’s “miraculous” test score gains after the State Education Department acknowledged last year that its tests had gotten easier over time.

It may be true, as Brill’s press release states, that the battle over school reform is “a monumental political struggle for the future of the country and for the soul of the Democratic party,” but the agenda he promotes has been warmly embraced by conservative Republican governors like Rick Scott of Florida, Scott Walker of Wisconsin, Chris Christie of New Jersey, Mitch Daniels of Indiana, Rick Snyder of Michigan, John Kasich of Ohio, and Tom Corbett of Pennsylvania. Brill never explains why the Democratic Party should support the most right-wing efforts to privatize public education and reduce the status of the education profession.

Brill does have one piece of news. He writes that Bloomberg started planning to overturn mayoral term limits and run for a third term as early as 2006, not in 2009—as he publicly claimed at the time—in response to the economic crisis of 2008. Because Bloomberg secretly intended to run again, Brill claims, he tied Joel Klein’s hands in negotiating with the teachers’ union and dramatically expanded the city’s pension liabilities while getting insignificant concessions from the union in return.

Brill’s book is actually not about education or education research. He seems to know or care little about either subject. His book is about politics and power, about how a small group of extremely wealthy men have captured national education policy and have gained control over education in states such as Colorado and Florida, and, with the help of the Obama administration, are expanding their dominance to many more states. Brill sees this as a wonderful development. Others might see it as a dangerous corruption of the democratic process.

As Brill’s narrative unfolds, the title of his book assumes a different meaning. The reformers Brill admires have Ivy League backgrounds—although there are certainly many Ivy League graduates and scholars who do not endorse the current definition of “reform”—and Brill identifies each of them with his or her pedigree from Princeton, Harvard, Yale, and other highly selective institutions. Class Warfare is not about a “classroom war,” but literally a “class war,” with a small group of rich and powerful people poised to take control of public education, which apparently has for too long been in the hands of people lacking the right credentials, resources, and connections.

Janet Grossbach Mayer represents the kind of person who is on the other side of the “class war.” In As Bad as They Say? Three Decades of Teaching in the Bronx, she vividly describes her life on the front lines of urban education. She went to public school in the Bronx and graduated from Queens College. She saw teaching as a career and a calling, not a stepping stone to policymaking or law school. Like most career teachers, she chose to teach where she grew up, which happened to be one of the poorest districts in the nation. Over many years as an English teacher, she taught 14,000 students. She wrote her book because she wanted the world to know that Bronx students, “contrary to expectations, were young people of remarkable character, unlimited potential, uncommon courage, and indomitable will.”

Like Brill, she is angry at the school system, but for very different reasons. What she experienced firsthand was “grossly underfunded schools,” with overcrowded classrooms, deteriorating and mouse-ridden buildings, and dirty bathrooms with no toilet paper or soap. Unlike Brill, she is critical of the fact that suburban schools “spend double, sometimes triple, the amount of money per student that New York City spends” and that schools generally continue to be racially segregated. Far from detesting the union at her school, she was grateful that it was there to fight for better conditions and to represent her when she had to deal with an abusive principal.

Her battles with the bureaucracy are a small part of the book. Most chapters tell the stories of her students, each of whom lived in difficult circumstances, struggling with daily challenges that would be beyond the imagination of those who live on Central Park South and Park Avenue. Many had asthma, exacerbated by exposure to exhaust fumes, or an allergy to cockroaches; students suffering from asthma found it difficult to climb the school building’s five flights of stairs when the elevator was out of order, which it often was. In the winter, students wore their coats inside all day because the lockers had been removed and not replaced many years before. Many students had “divided families, hostile families, distant families, no families” and lived in roach- and rat-infested buildings.

Whatever its inadequacies, and they were legion, the Bronx school provided the most stable institution in their lives, a place where a caring teacher or principal or guidance counselor could help them solve a crisis that threatened to destroy their fragile situations. One of Mayer’s students, Omara, asked her teacher to recommend an orphanage near the school; her father had been murdered during Christmas break, and his girlfriend could not afford to keep her. Mayer brought her to the school’s guidance counselor and social worker, who quickly found a city agency willing to provide the funding for her to remain in her home.

Ramika, a bright and eager student, failed some courses, but Mayer would not give up on her. Ramika lived in a building with no heat, electricity, or hot water. She was responsible for her ailing grandmother and her three younger sisters, with whom she shared a room and a bed. Ramika did all the cooking, cleaning, and shopping. Their mother, a crack addict, had “disappeared” on the streets. Mayer continually encouraged Ramika to apply herself to her studies and, as her grades improved, to fill out college applications. To Ramika’s amazement, she was accepted by the State University of New York at New Paltz, but could not afford to attend. A woman who had graduated from the high school forty-eight years earlier awarded a full college scholarship to the student who showed the most promise and was first in her family to go to college. On her graduation day, Ramika won.

In Mayer’s book, there is quite a lot of kissing and hugging: she often kisses her students, and they kiss her back. There is also a lot of crying, a lot of tears, shared freely by Mayer and her students. Their lives are hard, and she gives them whatever help she can. She never pries into their home lives unless they bring their problems to her, but she teaches them to read and selects articles and books for each student that will encourage them to read on their own. She creates a multicultural literature curriculum so that each one can see how people just like them succeeded. She tells them they must never give up, never stop trying. Her students, she insists, are heroes.

But there are scoundrels in her book, among them businessmen like Mayor Bloomberg who think they can run schools by numbers and mandates. There are also the distant policy-makers who insist that all students must meet one high standard to get a high school diploma, a goal that is beyond reach for many of Mayer’s students. Knowing that the new mandate would cause many students to give up and drop out, teachers were not surprised when the city’s Department of Education offered a dumbed-down retest for those who failed the Regents examinations. Anything to get those numbers up. Now the schools offer “credit recovery,” a dubious scheme that enables students to make up a failed year with a week or so of ersatz classes. The goal of these shabby manipulations is to hit the phony targets and make the leadership look good, even as they ignore the daily tribulations of students and teachers.

When test scores become the goal of education by which students and schools are measured, then students in the bottom half—who will inevitably include disproportionate numbers of children who are poor, children with disabilities, children who barely speak English—will be left far behind, stigmatized by their low scores. If we were to focus on the needs of children, we would make sure that every pregnant woman got good medical care and nutrition, since many children born to women without them tend to have learning disabilities. We would make sure that children in poor communities have high-quality early childhood education so that they arrive in school ready to learn. We would insist that their teachers be trained to support their social, emotional, and intellectual development and to engage local communities on behalf of their children, as Dr. James Comer of Yale University has insisted for many years. And we would have national policies whose goal is to reduce poverty by expanding economic opportunity.

In these two books, we have two versions of school reform. One is devised by Wall Street financiers and politicians who believe in rigidly defined numerical goals and return on investment; they blame lazy teachers and self-interested unions when test scores are low. The other draws on the deep experience of a compassionate teacher who finds fault not with teachers, unions, or students, but with a society that refuses to take responsibility for the conditions in which its children live and learn—and who has demonstrated through her own efforts how one dedicated teacher has improved the education of poor young people.

This Issue

September 29, 2011

Coming Attractions

After September 11: The Failure

-

1

Michael T. Nettles, Preface, in Paul E. Barton and Richard J. Coley, The Black–White Achievement Gap: When Progress Stopped (Education Testing Service, 2010), p. 2, available at www.ets.org. ↩

-

2

Howard L. Fleischman, Paul J. Hopstock, Marisa P. Pelczar, and Brooke E. Shelley, Highlights from PISA 2009: Performance of US 15-Year-Old Students in Reading, Mathematics, and Science Literacy in an International Context (National Center for Education Statistics, December 2010), p. 15, available at nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2011004. ↩