The following, the second part of a two-part series, is excerpted from a talk originally given by Saul Bellow in 1988 and now published here for the first time. A footnote has been added by the editors.

In reading Lionel Abel’s memoir, The Intellectual Follies, I came upon an arresting passage in his chapter on the Jews. During the war he had heard accounts of the Nazi terror, Abel says, and reports of extermination camps in Eastern Europe.

But I had no real revelation of what had occurred until sometime in 1946, more than a year after the German surrender, when I took my mother to a motion picture and we saw in a newsreel some details of the entrance of the American army into the concentration camp at Buchenwald. We witnessed the discovery of the mounds of dead bodies, the emaciated, wasted, but still living prisoners who were now being liberated, and of the various means of extermination in the camp, the various gallows, and also the buildings where gas was employed to kill the Nazis’ victims en masse.

It was an unforgettable sight on the screen, but as remarkable was what my mother said to me when we left the theatre: She said, “I don’t think the Jews can ever get over the disgrace of this.” She said nothing about the moral disgrace to the German nation…, only about…a more than moral disgrace, and one incurred by the Jews. How did they ever get over it? By succeeding in emigrating to Palestine and setting up the state of Israel.

I too had seen newsreels of the camps. In one of them, American bulldozers pushed naked corpses toward a mass grave ditch. Limbs fell away and heads dropped from disintegrating bodies. My reaction to this was similar to that of Mrs. Abel—a deeply troubling sense of disgrace or human demotion, as if by such afflictions the Jews had lost the respect of the rest of humankind, as if they might now be regarded as hopeless victims, incapable of honorable self- defense, and, arising from this, probably the common instinctive revulsion or loathing of the extremities of suffering—a sense of personal contamination and aversion. The world would see these dead with a pity that placed them at the margin of humanity.

“Certainly, the Holocaust was a tragedy,” Abel says. And with a writer’s weakness for literary categories, he begins to talk about theories of tragedy:

When we think of tragedy we must remember that the best critics of tragedy considered as an art have told us that at the end of tragedy there must be a moment of reconciliation. The human spirit, offended by the excesses of the pitiable and the terrible, has to be reconciled to the reality of things. Some good must come of so much evil; and for the Jews, this good was found only in the setting-up of the state of Israel. What came out of the Holocaust was the success of Zionism.

My note in the margin was “Do we really need to go into this?” I was far from sure that this was the time to bring down the curtain on the Fifth Act. The struggle still went on. What was certain however was that the founders of Israel restored the lost respect of the Jews by their manliness. They removed the curse of the Holocaust, of the abasement of victimization from them, and for this the Jews of the Diaspora were grateful and repaid Israel with their loyal support. Perhaps a more appropriate category than tragedy, if a category is what we need, would be epic, for centuries of continuous adherence to Jewish ideas does make one think of a long continuing epic, the dedication of a people to something far higher than itself.

In Germany the revival of the epical theme in Wagnerian and later in Hitlerian form may well have been a bid to supersede the Jewish epic. Even the plan to destroy the Jews was epical in scale. The building up of Israel was a further chapter in the epic of the Jews. It probably matters little which literary label one selects, but then I am speaking of Jews and literature, so it is not inappropriate to speculate about tragedy and epic, for what is suggested by the foregoing discussion is that in the modern world of nihilistic abysses and voids the Jews, through the horror of their suffering and their responses to suffering, stand apart from the prevailing nihilism of the West—if they wish to separate themselves from this nihilism they have such a legitimate option.

At the same time, I have often thought that it would be something of a miracle if they had not been driven mad by their experiences in this century. I look up Yeats’s poem “Why Should Not Old Men Be Mad?” and see what the provocations of his old men are: a likely lad who turns into a drunken journalist, a promising girl who bears children to a dunce. Yes, private tragedies—one should not minimize them. But put them up against the project of murdering an ancient people in its entirety, think of what it means that your Jewish birth may condemn you to death, and they seem negligible causes of madness.

Advertisement

And I sometimes glimpse in myself, an elderly Jew, a certain craziness or extremism, as if the vessel can no longer hold what is poured into it, and feel that my mental boundaries are crumbling. I occasionally think that I see evidences in Israeli politics of rationality damaged by memories of the Holocaust. And even if we were to accept Abel’s cathartic view of Israel and pronounce its Founding a successful Fifth Act—that play, the play of the Founding, may be over but Jewish involvement in the history of the West is far from concluded. Our own American chapter of it is certainly opened.

Times have changed (they always do, don’t they?) since Karl Shapiro published his book In Defense of Ignorance. I read it during the hopeful Sixties and the chapter on the Jewish writer in America left a permanent impression on me. In it Shapiro argues that Jewish creative intelligence has for centuries been driven into bypaths. “The fantastic intellectual powers of the Jews of our time go into everything under the sun except Jewish consciousness,” he wrote.

As far as one can tell these things, there are only two countries in the world where the Jewish writer is free to create his own consciousness: Israel and the United States…. The European Jew was always a visitor…. But in America everybody is a visitor. In this land of permanent visitors the Jew is in a rare position to “live the life” of a full Jewish consciousness. The Jews live a fantastic historical paradox: we are the spiritual aborigines of the modern world.

Here, says Shapiro, the American Jew has been able to “emerge from the historical consciousness to a full Jewish consciousness.”

Later, when Shapiro sees similarities between Judaic mystical humanism and American secular humanism, he loses me. But his prior assertion, namely that in the United States the Jewish writer is free to create his own consciousness, is most appealing.

But in creating his own consciousness, what are the limits our Jewish-American writer must expect to consider? I spoke earlier of the nihilistic abysses of the modern world and suggested that Jews, through the horror of Jewish suffering, the enormity of the Final Solution, might stand apart from the nihilism of the West. If they wished to separate themselves from this modern and European nihilism they might legitimately exercise the option. What did I mean by this?

These are difficult matters. I shall naturally be asked to define nihilism. What is it? We have our choice of a variety of definitions. For Nietzsche, nihilism signifies the abolition of all hitherto accepted measures and fundamental values. But that may be too broad to be useful. More to the point is the assertion that nihilism denies the existence of any distinct substantial self. This lack of self-substance makes all persons nugatory or insignificant. If we are insignificant, what does it matter what becomes of us? Still, those who are killed need not accept their definition from their killers or have their humanity taken from them as well as their lives. The burden of valuation is on the killer whose ground is nihilistic.

Let the country that committed the crimes bear the blame for them. The slain were not invited into Nothingness, they had it thrust upon them. We are free to withdraw (to withdraw our minds where we cannot withdraw our bodies) from situations in which our humanity or lack of it is defined for us. It was the judgment of the slayers that slaughter was permitted, that the slain had at best a trivial claim to existence based on an untenable fiction of inviolate selfhood. Theorists of euthanasia had long ago consented to the destruction of the unfit. Even mild vegetarian Fabians like G.B. Shaw (there were others) agreed that measures should be taken by a progressive society to rid itself of defective types. These socially and historically “progressive” reforms were applied in Central Europe by the Nazis with programmatic rigidity and also a kind of purgatorial irony to the Jews and other peoples judged superfluous. This is what causes me to speak of nihilism.

It would be a mistake on modern grounds to set aside as unimportant the age-long inclination of connecting the spiritual order in the universe with our own lives. In our pragmatic attitude toward the social order we leave no room for the influence of general beliefs on our own particular views of morality. In his recent short book Death of the Soul, the philosopher William Barrett offers a useful discussion of the consequences of the disappearance (the destruction, in fact) of the self. He examines critically Heidegger’s treatment of the human being. How, in Heidegger’s view, are we in the world? We ask of Heidegger, “Who is the being who is undergoing all these various modes of being? (Or, in more traditional language: Who is the subject, the I, that underlies or persists through all these various modes of our being?) And here Heidegger evades us.” “We are nothing,” he says, “but an aggregate of modes of being, and any organizing or unifying center we profess to find there is something we ourselves have forged or contrived.”

Advertisement

Thus there is a gaping hole at the center of our human being—at least as Heidegger describes this being. Consequently, we have in the end to acknowledge a certain desolate and empty quality about his thought, however we may admire the originality and novelty of its construction.

And Barrett asks, “How could a being without a center be really ethical?” He concludes:

[Heidegger] cannot be dismissed: that desolate and empty picture of being he gives us may be just the sense of being that is at work in our whole culture, and we are in his debt for having brought it to the surface. To get beyond him we shall have to live through that sense of being in order to reach the other side.

To this I should like to add that questions that can be closed by philosophic argument often remain open for art, and it is therefore a mistake for writers to accept the preeminence of the philosophers, and write poems, novels, and plays to illustrate, to confirm, to work out in their art and in human detail, the thoughts given to us abstractly by distinguished (and also by undistinguished) thinkers. (Cartesians, Kantians, Hegelians, Bergsonians, Marxians, Freudians, Existentialists, Heideggerians, etc.) Neither the philosopher nor the scientist can tell the artist conclusively, definitively, what it is to be human.

But enough of this for the moment. I was saying earlier that the fate of the Jews in the twentieth century was to suffer the cruelties of nihilistic thought and nihilistic politics. I did not say that Jews—the survivors and descendants themselves—escaped the desolate and empty picture of being that Barrett correctly tells us “is at work in our whole culture.” All of us living in the West must endure this desolation. The feelings it transmits, the motives it instills in us, the human states our surroundings make us familiar with, the invasive force of these states which we are constrained to submit to, the coloration they give to our personalities, the mutilations they inflict on us, the overwhelming shaping powers of a nihilism now commonplace do not spare anybody. The argument developing here, using me as its instrument, is that Jews, as such, are not exempt from these ruling forces of desolation. Jewish orthodoxy obviously claims immunity from this general condition but most of us do not share this orthodox conviction. Closely observed, the orthodox too are seen to be bruised by these ambiguities and the violence that our age releases impartially against us all.

Israelis are also apt to claim immunity, and to a degree the danger of destruction they have to face justifies this. But they too are part of the civilized West. They have necessarily adopted a Western outlook, Western techniques, Western arms, Western organization, Western banking, diplomacy, Western science. The defense of the Zionist state has led to the creation of a mini-superpower, and thus Israel is to a considerable degree obliged to share the malaise we all suffer—the French, the Italians, the Germans, the British, the Americans, and the Russians. Israel is narrowly watched by the West, and the Western press and public try hard to find evidences of Jewish evil and perhaps its aim is to implicate the Jews in its nihilism.

The formation of Israel was a response to the nihilistic rage of the two powerful European states that began the war, and the complicity of the rest who could not and perhaps would not protect their Jews, and Israel’s founders were aware of this. But the Western world now exhibits a certain unwillingness to sanction the Israeli solution—in other words, to let the Jews get away with it. As for Jews in France, England, and the United States claiming a share in the common life of their respective countries, they consent to share also in the desperate sense of non-being-in-being—to experience the gaping hole at the center of the self, that despair arising from the dying heart of every “advanced society.”

After these remarks on the actual situation of the Jew and the civilization from which he cannot now be separated, I should like to look again at the statement I made in 1976, by which that admirable scholar Gershom Sholem was so displeased—I am an American writer and a Jew. Or, I am a Jew and an American writer. Evidently it made him angry that I should see myself as a writer primarily. Most Americans, on seeing my name, probably say to themselves, “He is a Jew,” and then add, “He writes.” Here the priorities hardly matter. But I am not an assimilationist. As a Jew, however, I have long been aware of the political significance of America in world history, of the unparalleled hospitality of this country to all the branches of humanity.

Nevertheless, I am a Jew and as such I am made to understand by Jewish history that I cannot absolutely count on enlightened laws and institutions to protect me and my descendants. I observe the Jewish present closely and actively remember the Jewish past—not only its often heroic suffering but also the high significance of the meaning of Jewish history. I think about it. I read. I try to understand what it may signify to be a Jew who cannot live by the rules of conduct set down over centuries and millennia. I am not, as the phrase goes, an observant Jew, and I doubt that Scholem was wholly orthodox. He was, however, immersed in Jewish mysticism of the sixteenth century, and studied Kabbalism closely, so it is unlikely that he should have been devoid of religious feeling.

I, by contrast, am an American Jew whose interests are largely, although not exclusively, secular. There is no way in which my American and modern experience of life could be reconciled with Jewish orthodoxy. So that my ancestors, if they were able to see and judge for themselves, would find me a very strange creature indeed, no less strange than my Catholic, Protestant, or atheistic countrymen. Yet their scandalously weird descendant insists that he is a Jew. And of course he is one. He can’t be held responsible for the linked historical transformations of which he became the odd heir.

For writers in the West and particularly in the US, it is almost too late to resolve the difficulties described above. Hardly anyone now is conscious of them. Writers seldom give any sign that they are aware of the degree of freedom they enjoy here. Their privilege is to be unrestrained in their destructiveness. They show by this that our giant America does not own them. They are very prickly about not being owned. But then nobody takes them very seriously either. To state the matter more clearly, they are not held to account for their opinions. These opinions are a null dust—weightless.

What does this mean? Can it be said that in our dizziness we are annihilating even nihilism?

Jewish writers, if they wish to exercise their option to reject the nihilistic temper, may do so, but it will be all the better for them—for us all—if they do not get themselves up as spokesmen for conscience or try to give the world the business, as it were, by their moralizing.

I never wished to avoid being recognized as a Jew in order to escape discrimination. I never cared enough, never granted anyone much power to discriminate against me—and now it is too late to bother about such matters. My view, a view widely held, is that there is no solution to the Jewish problem. Viciousness against Jews will never end in any foreseeable future; nor will the consciousness of being a Jew vanish, since the self-respect of Jews demands that they be faithful to their history and their culture, which is not so much a culture in the modern sense as it is a millennial loyalty to revelation and redemption.

A philosopher whose views on the subject of Judaism have influenced me says that those modern Jews for whom the old faith has gone will prize it as a noble delusion.* Assimilation is an impossible—a repulsive—alternative. What is left to us is the contemplation of Jewish history. “The Jewish people and their fate are the living witness for the absence of redemption,” this philosopher writes. And he states further that the meaning of the chosen people is to testify to this:

The Jews are chosen to prove the absence of redemption. It is supposed…that the world is not the creation of the just and living God, the Holy God, and that for the absence of righteousness and charity we sinful creatures are responsible. A delusion? A dream? But no nobler dream was ever dreamt.

This is not incompatible with Karl Shapiro’s assertion that in the United States the Jewish writer is free to create his own consciousness. In creating it he will find it necessary also to contemplate Jewish history and to attempt to discover its inmost meaning. For a modern man this is perhaps what constitutes a Jewish life.

I said at the beginning of this talk, “My first consciousness was that of a cosmos, and in that cosmos I was a Jew.” After seventy-odd years, some fifty of which have been spent in writing books, I can do no more than describe what has happened, can only offer myself as an illustration. The record will show what the twentieth century has made of me and what I have made of the twentieth century.

—This is the second of two parts.

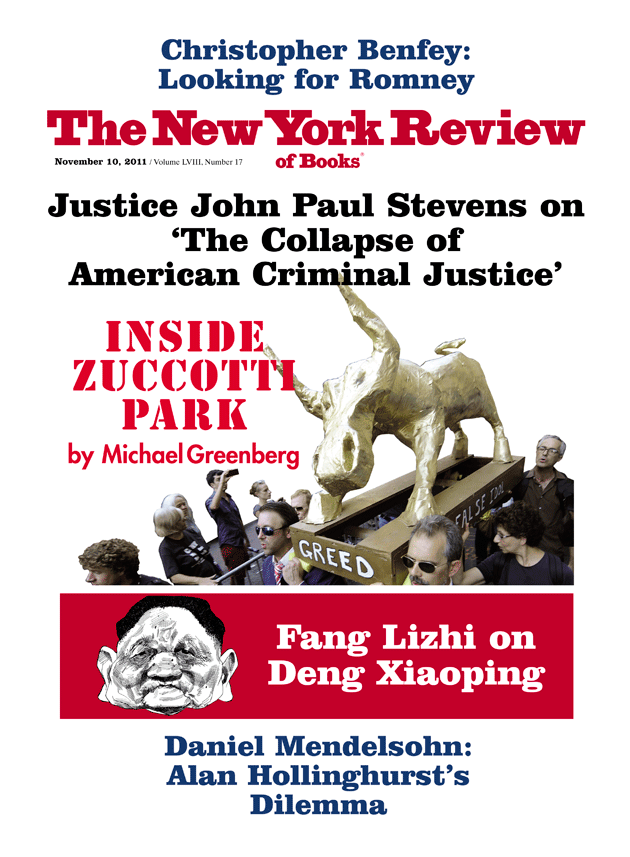

This Issue

November 10, 2011

Our ‘Broken System’ of Criminal Justice

The Real Deng

In Zuccotti Park

-

*

See Leo Strauss’s lecture “Why We Remain Jews,” included in his Jewish Philosophy and the Crisis of Modernity: Essays and Lectures in Modern Jewish Thought, edited by Kenneth Hart Green (State University of New York Press, 1997). ↩