1.

Two great English writers, both born in 1903 and not so dissimilar in background, stood far apart in their work and their beliefs: George Orwell the socialist agnostic essayist (and novelist) and Evelyn Waugh the conservative Catholic novelist (and essayist). But they knew one another—Waugh visited Orwell in the sanatorium where he was dying—and they admired each other. At the time of his death Orwell was planning an essay on Waugh, with the faintly condescending theme that he was as good a writer as it was now possible to be while holding intolerable opinions, and in 1946 Waugh admiringly reviewed the first collection of Orwell’s essays.

A further link between the two was their shared fascination with another writer a generation older, about whom they corresponded, and whom they both discussed in print at some length. Orwell’s essay “In Defence of P.G. Wodehouse” was originally published in July 1945, when its subject thanked Orwell:

It was extraordinarily kind of you to write like that when you did not know me and I shall never forget it…. It was a masterly bit of work and I agree with every word of it.

Waugh commended the essay, although he took issue with some of its points. And years later, to celebrate Wodehouse’s eightieth birthday in 1961, although also on the twentieth anniversary of another broadcast, Waugh gave a talk on BBC radio entitled “An Act of Homage and Reparation.”

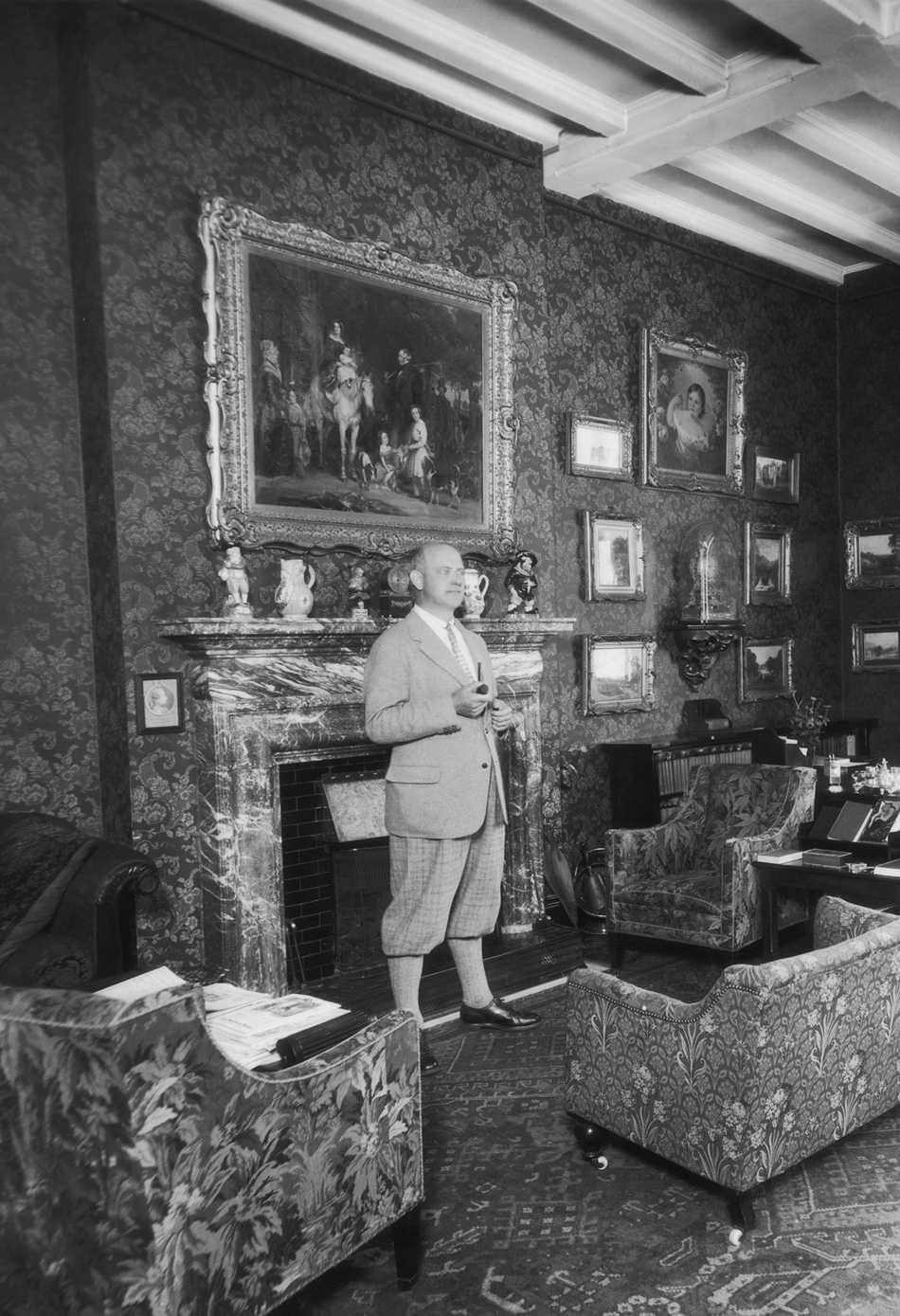

A “defence,” and perhaps a “reparation,” had become necessary after the most—or indeed only—dramatic event in the life of that wonderfully gifted and prolific writer but strange and mystifying personality. In 1939, Wodehouse was fifty-eight and at the height of his fame and fortune. His books were widely read in many countries, while he had made very successful further careers in American popular entertainment. But he also enjoyed, to a most unusual degree for a light-hearted farceur, the esteem of serious writers, scholars, and statesmen: Orwell and Waugh apart, his admirers have ranged from Asquith, Belloc, and Wittgenstein to Auden, Aldous Huxley, Lionel Trilling, and Garry Wills. His tales of Psmith and Ukridge, of Bertie Wooster and Jeeves, of Lord Emsworth and Mr. Mulliner, written in exquisite fantastical prose, were relished both by those who read nothing else and those who read everything.

That summer Wodehouse went to Oxford to receive an honorary doctorate, which was particularly gratifying (“apparently a biggish honour,” he said in his unassuming way) forty years after he had longed, but been unable, to go there as an undergraduate. After the academic ceremony in June he returned to Le Touquet, on the French side of the Channel, where he and his wife Ethel had made their home since 1935, a resort the English then tended to associate with golf and adultery, although it was also where Jacques Chirac met Tony Blair just before the invasion of Iraq ten years ago, when the French president lucidly but unavailingly foretold that the invasion would very likely precipitate civil war.

No more prescient than Blair, Wodehouse had written that April to William Townend, a schoolfriend and his most frequent correspondent, “no war in our lifetime is my feeling.” When the war did come in September the Wodehouses stayed put, quite unconcerned. But then, as Bertie observes, “it’s always just when a fellow is feeling particularly braced with things in general that Fate sneaks up behind him with a bit of lead piping.”

Born in 1881, Pelham Grenville Wodehouse—“Plum” to his friends—came from a minor and landless branch of what was still called landed gentry, with many distinguished connections. His distant cousin John, Lord Wodehouse, became Gladstone’s colonial secretary and first Earl of Kimberley; his maternal grandfather was a clergyman; his father a magistrate in Hong Kong, where his salary and then pension were paid in rupees.

Plum barely saw his parents during his childhood, which was spent at a succession of boarding schools and, in the holidays, with uncles (of whom he had fifteen) and of course aunts (he had twenty), a species who were to feature so much in his books. He won a scholarship to Dulwich, a socially modest but academically excellent school in suburban south London, and there he spent the happiest years of his life. An ardent schoolboy cricketer and rugby player, Wodehouse returned to Dulwich for decades afterward to watch matches, and he followed reports of the school teams from afar all his life.

He was also a good classicist and should have followed his elder brother Armine to Oxford, but for Fate’s lead piping. “Cecily, you will read your Political Economy in my absence,” says Miss Prism in The Importance of Being Earnest. “The chapter on the Fall of the Rupee you may omit. It is somewhat too sensational.” (Although Wodehouse, maybe significantly, never mentioned Wilde, he must have known his most famous play. Lane, Algernon’s manservant, is a prototype for Jeeves, and Lady Bracknell for Aunt Agatha.) When the rupee did fall at the wrong moment the effect, if not quite sensational, was sorrowful. His father’s reduced income meant that Plum was instead exiled to the City office of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank.

Advertisement

His escape was “A Life in Letters.” That is the apt title, with its gentle double meaning, under which Wodehouse’s letters have now been published, edited in exemplary fashion by Sophie Ratcliffe. An unusually well-read Wodehousian, she is an Oxford don, and there is something amusing about such learned meticulosity devoted to an essentially frivolous writer.

But not an indolent or easygoing one. From the very beginning, as he wrote for cheap papers and schoolboy magazines, Wodehouse was an industrious professional craftsman who knew his worth. At twenty-one he was already negotiating with publishers, at twenty-four he asked an agent to represent him, saying that he had “made a sort of corner in public-school stories” and was earning good fees, “but I fancy that judicious management could extract more.” In 1904 he visited New York for the first time and he was soon a regular trans-Atlantic commuter.

Just as hostilities began in 1914, Wodehouse returned to America, but when he says in a letter from New York on September 1 that “The state of the War is as follows,” he is writing about negotiations with magazines, not the slaughter in Europe. Far from the battle, he was “busy getting married to Ethel Milton!” They were an unlikely match. The extravagant, extroverted, and sometimes exhibitionistic Ethel was born poor and out of wedlock in Norfolk. She became a dancer, and then became pregnant, married and buried two husbands, and returned to the stage to support Leonora, her daughter. After their brief courtship, she and Plum moved to Long Island. Wodehouse adopted Leonora as his own daughter and she—“Darling Snorky,” “angel Snorklet”—became almost the strongest human attachment of his life.

He later worried that he would be criticized “for not helping to slug Honble Kaiser,” and wrote with nervous whimsy that he had registered in the American draft as “age sixty-three, sole support of wife and nine children, totally blind.” We would be the losers if Plum had been killed, but Waugh later spotted something that Orwell had missed, and which became relevant a quarter-century after Plum’s absence from the first war: a “strain of pacifism” in Wodehouse:

When Mr. Orwell and I were at school [after the Great War], patriotism, the duties of an imperial caste, etc., were already slightly discredited; this was not so in Mr. Wodehouse’s schooldays, and I suggest that Mr. Wodehouse did definitely reject this part of his upbringing.

Bertie Wooster is plainly of military age, Waugh observed, while “It was in the dark spring of 1918 that Jeeves first ‘shimmered in.’” (Jeeves actually appeared earlier, in a 1915 Saturday Evening Post short story.)

Those war years were exceptionally fruitful and lucrative for Wodehouse. He now developed far beyond schoolboy fiction and Edwardian jocosity into the ethereal ludic fantasy of the Jeeves and Wooster books, of Lord Emsworth and Blandings, written with what Waugh called an “exquisite felicity” of language. And he found another field for his talent, as a song lyricist (or “lyrist,” as he preferred). With Jerome Kern writing the wonderful scores, Wodehouse and his fellow lyricist Guy Bolton pretty much created the Broadway musical, with shows like Oh, Boy! and Oh, Lady, Lady! Ten years later, Kern would reach the peak with Show Boat, which includes “Bill,” just the one lovely lyric by Plum.

Returning to England, he was delighted to find that his fame had grown: reviewers would now say that someone is “a sort of P.G. Wodehouse character” or write of “the P.G. Wodehouse manner.” By 1927, he and Ethel lived in Mayfair with ten servants, including a chauffeur for the Rolls Royce. He continued to travel to and from America, writing novels, plays, stories, and letters. It should be said that, unlike Wilde, Wodehouse put his genius very much into his work rather than his life, and the letters, while amusing and genial, are rarely dazzling, largely concerned with work and money: “I’ve just done 100,000 words of a new novel in exactly two months…. I got $8000 for Piccadilly Jim.”

That payment was in earlier days. In 1929, “an era when only a man of exceptional ability and determination could keep from getting signed up by a studio in some capacity or other,” he moved to Hollywood. On top of the $50,000 he now commanded for a magazine serial, he was paid a weekly $2,000 by MGM (at a time when an American auto worker made around $30 a week). This inspired his tales about the studios, with their hierarchy of Yes-Men and Nodders, but he found Hollywood “loathsome,” and complained that “the actual work is negligible.” Much happier was Leonora’s marriage in 1932 to Peter Cazalet, a rich, dashing sportsman: they had once seen him make a century for Eton at Lord’s in cricket. He was “not only a sound egg,” Plum reported, “but probably the only sound egg left in this beastly era of young Bloomsbury novelists.”

Advertisement

2.

At a Hollywood party in 1929, Plum met another visiting Englishman, who didn’t recognize him. “This was—I think—the seventh time I have been introduced to Churchill,” Wodehouse reported, “and I could see that I came upon him as a complete surprise once more.” But in October 1939, at his house in Le Touquet, he hears “a fine speech of Churchill’s on the wireless…. Just what was needed.” And two months later, “I have been reading all Churchill’s books…. They are terrific…. What mugs the Germans were to take us on again.”

On May 10, 1940, Winston Churchill became prime minister, the day after the Wehrmacht had attacked in the West. The Wodehouses at last tried to leave France, but too late. The next missive is on October 21, to Paul Reynolds, his agent in New York:

WILL YOU SEND ME A FIVE POUND PARCEL ONE POUND PRINCE ALBERT TOBACCO, THE REST NUT CHOCOLATE. REPEAT MONTHLY. AM QUITE HAPPY HERE AND HAVE THOUGHT OUT NEW NOVEL.

These capitals are picked out on a “Kriegsgefangenenpost” card from Tost, an internment camp in Silesia. The next years don’t really belong to his “life in letters,” of which he wrote few: the details of the sorry story have been related in Robert McCrum’s excellent 2004 biography.

Having been interned by the Germans as they swept to the Channel, Wodehouse was allowed to meet two American journalists, with disastrous results. He was taken to the Adlon Hotel in Berlin, befriended by plausible German go-betweens, and in June 1941 persuaded to make radio broadcasts. As Orwell said, their theme was largely “that he had not been ill treated and bore no malice.” They contained no political message, and in no real sense did they give aid and comfort to the king’s enemies. But their facetious tone was and remains unseemly in the circumstances of time and place.

These broadcasts were intended primarily for an audience in the United States, still neutral; in England the reaction ranged from astonishment to outrage. The anger was stoked by ugly propaganda. Egged on by Duff Cooper, Churchill’s minister of “information,” the journalist William Connor broadcast a venomous attack (despite the protests of the BBC governors), calling Wodehouse a traitor who had sold his country for a soft bed in a Berlin hotel, and linking his base conduct with the decadent settings of his books.

As the months went by, Wodehouse began to realize the grave trouble he was in, and hoped he might be allowed to leave Germany. Instead he and Ethel wandered from Berlin to various country houses where they were entertained by friendly Germans. Then they were shuttled to Paris, and were there when Allied troops liberated the city in 1944. Wodehouse was interrogated by Major Edward Cussen, a MI5 officer, but also befriended by Orwell, and another Englishman: “We have tried at times to express all we feel about your wonderfulness to us,” Wodehouse later wrote to Major Malcolm Muggeridge. But their advocacy did little good. Plum and Ethel managed to reach New York in 1947, and settled in Long Island where they lived until his death at ninety-three in 1975; he never saw England again.

He continued to write with the same prolificity though perhaps not quite the same marvelous élan, which to this day defies analysis.* Over in Cambridge, the Oxford degree and the cult of Wodehouse sent F.R. Leavis and his sectaries into frenzies of rage, which was enjoyable in itself, and Leavis damned his “stereotyped humour.” But Wodehouse is in fact highly original. Like Dickens before and Waugh after, he created characters who have become part of our mental furniture. When a well-known writer in conversation describes one of his confreres as Gussie Fink-Nottle (“many an experienced undertaker would have been deceived by his appearance and started embalming him on sight”), or a London literary editor as Aunt Agatha (she who “chews broken bottles and kills rats with her teeth”), there is, for some of us, immediate recognition.

Along with his famous gift for silly but sublime simile, there are other devices. Sophie Ratcliffe mentions transferred epithet—“I balanced a thoughtful lump of sugar on my teaspoon”—and one might add featherlight irony: it was unkindly said of the Vicomte de Blissac in Hot Water that he was never sober, which was not only unkind but untrue, since “he was frequently sober, sometimes for hours at a time.” Then there is farce, of the highest level, from the search for the missing boot in Mike, much the best of the school stories, to the immortal prize-giving at Market Snodsbury Grammar School in Right Ho, Jeeves, when the abstemious Gussie is surreptitiously plied with drink before addressing the “Ladies—boys and gentlemen—we have all listened with interest to the remarks of our friend here who forgot to shave this morning.”

And there is the old English tradition of fantasy-nonsense. Gussie’s consuming interest is newts (“Oh, yes, sir,” says the omniscient Jeeves. “The aquatic members of the family Salamandridae which constitute the genus Molge”). He arrives at Bertie’s flat dressed as Mephistopheles for a costume ball, saying that he is tongue-tied with girls, and wishes he could declare his love to Madeline Bassett as easily as a male newt does, by vibrating his tail in front of a female.

“But if you were a male newt, Madeline Bassett wouldn’t look at you. Not with the eye of love, I mean.”

“She would, if she were a female newt.”

“But she isn’t a female newt.”

“No, but suppose she was.”

“Well, if she was, you wouldn’t be in love with her.”

“Yes, I would, if I were a male newt.”

A slight throbbing about the temples told me that this discussion had reached saturation point.

That shows, by the way, why dramatizations of the books never really work: what makes the passage perfect is not just the dialogue but the last line of narration.

3.

Was Wodehouse innocent? The question isn’t intended in a legal sense, although when Cussen interrogated him, it sank in on Wodehouse that he was under suspicion on what was technically a capital charge. No charges were brought, but nor was there any sympathy from the man who never recognized him. “His name stinks here,” Churchill said, “but he would not be sent to prison…. He can live secluded in some place or go to hell as soon as there is a vacant passage.” The Labour government that took office in 1945 was no improvement, with the Attorney General Sir Hartley Shawcross (“an Old Alleynian, blast him!” Wodehouse exclaimed about this other Dulwich alumnus) refusing to say that Wodehouse was safe from prosecution. In fact, Cussen had cleared Wodehouse of any charge worse than stupidity, but the malevolent authorities did not release this for decades.

In his 1961 “Reparation” for Connor’s vulgar diatribe, Waugh insisted with defiant perversity that Wodehouse was quite blameless and that there was nothing wrong at all with the wartime broadcasts. To his credit, Wodehouse didn’t say that: “I am not attempting to minimise the blunder, which I realize was inexcusable.” Not that everyone accepted the plea of naive blundering. “I do not want to see Wodehouse shot on Tower Hill,” Harold Nicolson said at the time,

but I resent the theory that “poor old P.G. is so innocent that he is not responsible.” A man who has shown such ingenuity and resource in evading British and American income tax cannot be classed as unpractical.

It was true that Wodehouse hated paying tax, and he and his lawyers devoted a good deal of time to fighting all the way to he highest courts, but even there could be seen his strange if characteristic mixture of qualities—astute and heedless at once. He often chose his advisers badly, placing his American financial affairs at one time in the hands of a man who was incompetent or dishonest or both, and who disastrously failed to file any tax returns for several years.

And then there is his innocence in another sense: the complete sexlessness of his books was notable even within the conventions of his time, with not a hint of carnality. Sex jokes in some form or other have after all been a staple of Western comedy at least since Aristophanes wrote Lysistrata, and the total absence of any such joke was, as Orwell observed, a huge deprivation for a comic writer. Waugh dismissed this: “Mr. Wodehouse must know as well as anyone else what are the amorous adventures of young, rich bachelors in London.” The courtly love of the young men of the Drones Club is part of the books’ utter artificiality, Waugh said, just as their language was “never heard on human lips. It is all part of Mr. Wodehouse’s invention, or rather inspiration.”

Plainly, someone who spent part of his life on Broadway and in Hollywood could not be ignorant of the vagaries of lust, but in his later years Wodehouse was disgusted by the indecency of contemporary fiction. Then again, a man who found Nancy Mitford’s novels “dirty” was truly shockable, and there is something not merely underdeveloped but almost emotionally autistic about him. The editor deals with any personal speculation nicely by reminding us of the moment in Thank You, Jeeves when Bertie says that “The attitude of fellows towards finding girls in their bedroom shortly after midnight varies. Some like it. Some don’t. I didn’t.” As Ratcliffe suggests, Wodehouse himself seems to have come into the same category as Bertie. Indeed, one letter from 1920 confirms that he and Ethel slept in separate bedrooms.

Just as he excluded deep feeling and violent passion, he excluded serious thought. When he said in one of his broadcasts that “I never was interested in politics. I’m quite unable to work up any kind of belligerent feeling,” it was true enough. It was not that Wodehouse was oblivious of the great world: his topical observations can be very shrewd. In 1936 President Roosevelt ran for reelection and was ferociously traduced in the Hearst newspapers, before winning an overwhelming victory, carrying forty-six out of forty-eight states. Then in December the royal crisis exploded in London and the same papers campaigned noisily for Wallis Simpson to become queen of England, before Edward VIII abdicated. Just afterward, Wodehouse wrote from Beverly Hills that he had been to the movies:

When…Mrs Simpson came on the newsreel there wasn’t a sound…. It shows once more how futile the Hearst papers are when it comes to influencing the public. He roasted Roosevelt day after day for months, and look what he done! What people buy the Hearst papers for is the comic strips.

But as Ratcliffe says, “Political events were marginal to his imaginative life,” and he simply shut out the horrors of his time.

There are occasional oversights in this admirable edition. When Leonora married she acquired a brother-in-law and a sister-in-law, Victor Cazalet and Thelma Cazalet-Keir, who were both MPs. To say merely that Victor was “killed on active service” is inadequate. A supporter of both the Zionist and the Polish causes (an unusual combination), Cazalet visited Palestine in 1943, where he told a meeting led by David Ben-Gurion that “I would gladly give my life for the establishment of a Jewish state,” before he joined General Władysław Sikorski, the Free Polish commander, as a liaison officer. They were killed in July when their aircraft crashed after taking off at Gibraltar.

In what proved to be his last Commons speech in May 1943, Victor Cazalet had spoken of “the horrors of the massacres at a camp called Treblinka,” and here we come back from the beguiling Arcadia of Blandings to hideous reality. Even allowing for Wodehouse’s unworldliness, the letters are in some ways more exasperating than the broadcasts. “Do you know Berlin at all?” he asks Reynolds. “It is a very attractive city and just suits me.” This was written on November 27, 1941, two weeks before Hitler’s declaration of war on the United States and “the circle of Jews around Roosevelt,” and several weeks after deportations from Berlin to the killing centers began.

“I have always got on splendidly with Jews,” Wodehouse wrote in 1948. “You couldn’t want better chaps than fellows like Irving Berlin, Oscar Hammerstein, Ira Gershwin, Arthur Schwartz etc.” Seven years earlier he hadn’t noticed that the attractive city of Berlin was being emptied daily of other chaps, and women and children.

“It is nonsense to talk of ‘Fascist tendencies’ in his books,” Orwell said. “There are no post-1918 tendencies at all,” but that is not the whole story. The 1938 novel The Code of the Woosters contains a derisive portrait of Sir Roderick Spode, the ludicrous demagogue who leads the Black Shorts, patently guying Sir Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists and the Blackshirts. That shows that Wodehouse saw how absurd fascism was. But then absurdity was his stock in trade; Evil was quite beyond him.

Maybe that is part of what captivates us still. In felicitous words, Auden called The Importance of Being Earnest “perhaps the only purely verbal opera in English,” and Wodehouse’s books might be thought another kind of verbal music. And there is, yes, the innocence of Wodehouse, from “one of the great English experts on Eden,” in another phrase of Auden’s. That was the same word that Waugh used: Wodehouse’s characters “are still in Eden. The gardens of Blandings Castle are the original garden from which we are all exiled.” That is why we still love the books, set in what Waugh rightly called “a world as timeless as that of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Alice in Wonderland”; by happy contrast with the mundane triumphs and disasters of Wodehouse’s everyday life, it is “a world for us to live in and delight in.”

-

*

Thanks to Everyman Press of London, a new collected edition, The Everyman Wodehouse, will contain all the novels and stories newly edited and reset from the British edition. A similar edition, The Collector’s Wodehouse Series, is being issued in the US by Overlook Press. ↩