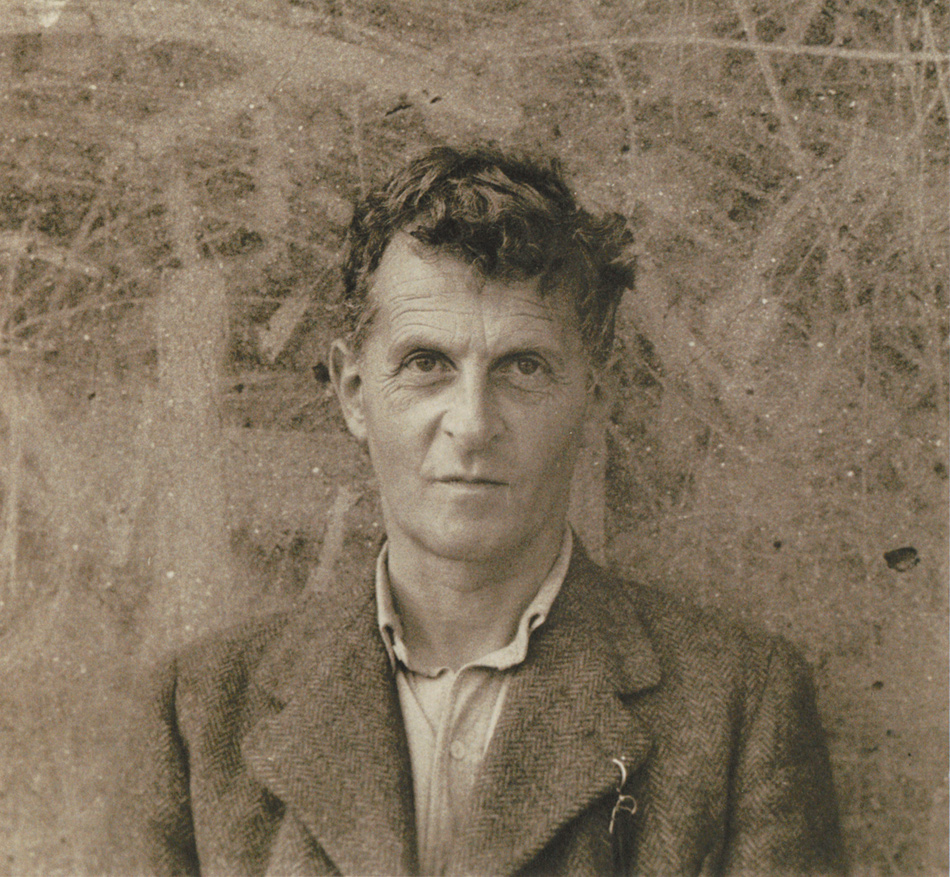

“Perhaps the best place to begin trying to understand Wittgenstein’s character,” the British philosopher Colin McGinn once remarked, “is with the photographs that exist of his face.” Looking into Wittgenstein’s eyes, McGinn went on, it is hard to meet his gaze for very long:

They are imploring eyes yet with an intense rage flaring just behind the iris, sending off an unnerving blend of supplication and admonition…. The look is simultaneously delicate and military, tender and ferocious. If you stare hard at the face, it seems to shift aspect from one of these poles to the other…. You feel the excitement and peril of an encounter with the man.

It is possible to be fairly sure which pictures McGinn has in mind here, since there are relatively few surviving photographs of the great philosopher and, of those, only a handful show him looking straight into the camera. Because so many books on Wittgenstein have been published since his death in 1951, most of these pictures have been reproduced many times and have thus become very familiar. Best known, perhaps, is the one taken in Swansea in 1947, which shows Wittgenstein, then fifty-eight years old, standing in front of a graffiti-laden wall, his lined face gazing into the camera with precisely the combination of tenderness and ferocity McGinn describes.

That image forms the cover of Ludwig Wittgenstein: Ein biographisches Album, a handsome, beautifully produced book that contains just about every surviving photograph of Wittgenstein, together with many others of his friends, his family, and the places where he lived and worked. What is unusual about this book is that there is almost no text linking the photographs or attempting to explain their background. In place of such commentary, we have extracts (usually in German, but sometimes in English) from Wittgenstein’s letters, his journals, and his philosophical writings, together with extracts from the writings of his family members and friends.

The book is the direct descendent of the 1983 volume Ludwig Wittgenstein—Sein Leben in Bildern und Texten, edited by Michael Nedo together with Michele Ranchetti, an Italian poet, historian, and all-around intellectual who died in 2008. Indeed, so large is the overlap between the two books (I would say roughly 90 percent of the pictures and texts in this new book were also in the old one) that it might be more natural to regard this book as merely a second edition of its predecessor, except that that is not how it bills itself. The earlier book is not mentioned anywhere on the cover, the title page, or among the bibliographic details of this new volume. In fact, as far as I can see, the only mention of it is in Nedo’s acknowledgments, in which he thanks his erstwhile coeditor, “with whom I edited the 1983 Suhrkamp biography, Ludwig Wittgenstein—Sein Leben in Bildern und Texten.” This makes it sound as if the earlier book were not only different, but a different kind of thing, a biography rather than a “biographical album.” This, however, is misleading. Not only are the images and the texts largely the same, but so is much of the accompanying apparatus: the chronology, the list of sources, and so on. If “biographical album” is an appropriate description of this new book, then it also fits the old one.

I never knew, or ever met, Michele Ranchetti, so cannot hazard a guess about what he might have thought of being airbrushed out of his own joint creation in this way, but the fact that this book is largely identical to the earlier jointly edited work makes its back-page blurb sound a little overblown:

Michael Nedo, who knows the works and life of Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) like few others, has with this volume produced a magnificent monument to this most influential of twentieth-century philosophers…. Text and images reveal the complex connections between Wittgenstein’s life and work and provide an excellent introduction to his thought.

Ranchetti might be one of the “few others” alluded to in this blurb, but even so it does not give him sufficient credit for his role in the creation of this “magnificent monument.”

The earlier volume made more modest claims. Its central aim, according to a postscript jointly written by Nedo and Ranchetti, was to demonstrate the connections between Wittgenstein’s life and work that had previously been ignored by commentators on his philosophy. That such connections had been ignored altogether was not entirely true even in 1983, but now, after the publication of Brian McGuinness’s biography in 1988, my own biography in 1990, and the countless articles and books that followed, there cannot be any doubt that such connections are receiving a great deal of attention.

The earlier volume contained an essay by McGuinness on “Wittgenstein’s Personality” that has now been replaced by a preface by Nedo that repeats much that was said in the earlier postscript. What is new in this preface is an emphasis on the idea announced in the title of this new book, the idea of an “album.” As Nedo makes clear, the notion of an album has a special significance in the understanding of Wittgenstein’s writings. In his preface to Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein described his work as “really only an album.” What he meant was that he had written the work as discrete paragraphs rather than as a sequential whole. His philosophical remarks, he said, resisted being brought together into such a whole, for they were

Advertisement

soon crippled if I tried to force them on in any single direction against their natural inclination.——And this was, of course, connected with the very nature of the investigation. For this compels us to travel over a wide field of thought criss-cross in every direction.—The philosophical remarks in this book are, as it were, a number of sketches of landscapes which were made in the course of these long and involved journeyings.

The same or almost the same points were always being approached afresh from different directions, and new sketches made. Very many of these were badly drawn or uncharacteristic, marked by all the defects of a weak draughtsman. And when they were rejected a number of tolerable ones were left, which now had to be arranged and sometimes cut down, so that if you looked at them you could get a picture of the landscape.

Just as Wittgenstein’s notion of Philosophical Investigations as an album emphasizes the importance of the arrangement of his remarks, so the great skill in editing the books produced by Nedo and Ranchetti lies not in what they themselves have written (which, apart from the preface and the earlier postscript, is more or less confined to the book’s apparatus: its chronology, notes, and references), but rather in the artful way in which they pair the pictures with the texts. For example, the very first picture in the book (in both its manifestations)—a studio portrait of the infant philosopher, captioned “Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein, born on 26 April 1889 in Vienna”—is accompanied not with a description of the house or the family into which he was born, but rather with two philosophical remarks. The first, written on April 21, 1951, just a week or so before his death, is from On Certainty:

My name is “L.W.” And if someone were to dispute it, I would straightaway make connections with innumerable things which make it certain.

The second, written in 1931, is one of a series of remarks that was published in 1979 as Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough:

Why should it not be possible that a man’s own name be sacred to him? Surely it is both the most important instrument given to him and also something like a piece of jewellery hung round his neck at birth.

On this very page both the strengths and the limitations of the book’s method of composition are revealed. If one already knows these remarks, then seeing them in this context forces one to read them anew, to look at them “under a different aspect,” as Wittgenstein would say. However, if one has never seen these remarks before, and does not know their original context, then seeing them paired with a photograph of the baby Ludwig and a caption giving his full name at birth would give a rather misleading impression of what they are about and why Wittgenstein said them.

This shows why the claim in the blurb that this book provides an “excellent introduction” to Wittgenstein is exaggerated if not entirely false. Taking these remarks out of their original context and giving them this new dimension, though an interesting thing to do, is surely not the ideal way to introduce people to them. For the reader of this book who has not read either On Certainty or Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough will have no means of knowing that the first is part of a series of remarks analyzing the concept of certainty and the second is part of Wittgenstein’s attempt to show what is wrong with Sir James Frazer’s approach to the understanding of “primitive” religious and magical rituals and beliefs.

On a positive note, however, this first page shows one very big advantage the new book has over its predecessor: whereas the previous book was entirely black and white, in this one the pictures are reproduced so as to resemble as closely as possible the originals, whether those were black and white, sepia, or full color. The difference this makes is surprisingly significant. This first image of Wittgenstein as a baby, for example, is so much more evocative now that one can see the yellowy hues of the original print.

Advertisement

After a few pages of the infant Ludwig, the book takes us back to Wittgenstein’s great-grandfather, Moses Mayer, who worked for the aristocratic Wittgenstein family and who, after the Napoleonic decree of 1808 that demanded that Jews adopt a surname, took the name of his employer. His son, Hermann, took a further step to separate himself from his Jewish ancestry by taking the middle name “Christian.” He is shown here in a fine mid-nineteenth-century photographic portrait, looking every bit the prosperous wool-merchant he was, with white hair, mutton-chop whiskers, a high collar, and an unbendingly stern expression. He and his wife, Franziska (“Fanny”), had eleven children, whom they brought up within the Protestant faith.

The life Hermann and Fanny provided for their offspring was one of great comfort, as represented here by a photograph of the extremely elegant Palais Kaunitz in Laxenburg, just outside Vienna, which was the family home. Built in the early eighteenth century, this beautiful and stately palace had previously housed the ambassador of Piedmont and then Prince Esterházy. Ludwig Wittgenstein knew it as the home of his Aunt Clara, who lived there until her death in 1935. Wittgenstein seems to have been rather fond of his aunt, who is pictured here in a photograph reproduced from a page in his own “photo-album,” which looks like a school exercise book with lined pages.

Mozart probably performed in the Palais Kaunitz, which was possibly one reason why Herman and Fanny, who were great music lovers, were drawn to it. Mainly through Fanny, the Wittgensteins had close ties to the leading figures in the cultural life of Austria. They acquired an impressive collection of paintings, they were friends of the poet Franz Grillparzer, and they counted among their acquaintances Johannes Brahms (who gave piano lessons to their daughters) and Felix Mendelssohn.

Against this background of wealth and privilege, it seems strange to describe Ludwig Wittgenstein’s father, Karl, as a self-made man, and yet that is what he was. He was fiercely independent and determined to succeed on his own. So much so that, turning his back on the advantages of his family background, he ran away to New York, where he made a living as a waiter, a saloon musician, a bartender, and a teacher. When he returned, he did so on his own terms, forsaking the family business of estate management in favor of engineering. Within a few years he was head of a cartel that held a virtual monopoly of the iron and steel industry in the Hapsburg Empire, and had become one of the wealthiest men in Europe. By the time he retired from business in 1898, his personal fortune was on a scale that dwarfed that of his father.

In the meantime, he had married Leopoldine (“Poldy”) Kalmus, with whom he had nine children (one of whom died), the youngest of whom was Ludwig. The Wittgenstein family owned a great number of houses, several of which were palatial, but their principal residence, the one that was considered home by Ludwig, his three sisters, and his four brothers, was the Palais Wittgenstein in the Alleegasse (now Argentinierstrasse) in Vienna’s fourth district. Conveying the grandeur of this remarkable house are photographs of its stately marble staircase, its lavishly decorated “red salon,” and its music salon, in which Johannes Brahms and the famous violinist Joseph Joachim played regularly for the family and their guests.

Wittgenstein Archive, Cambridge

A composite photo made by superimposing a portrait of Ludwig Wittgenstein with portraits of his three sisters, Hermine, Margarethe, and Helene. Ray Monk writes, ‘The eyes, the nose, and the mouth look like they belong to the same person, enabling one to see directly the very strong family resemblances that existed between

these four siblings. The notion of “family resemblances” is crucial to Wittgenstein’s later philosophy.’

Photographs of Ludwig Wittgenstein as a boy reveal him to be an entirely characteristic product of the Austrian high bourgeoisie. In quick succession, we see him with his horse, Monokel, and then we see him dressed for dinner at the family’s country estate in traditional Tyrolean costume, and then, at the age of eleven, in a sailor’s suit. Much of the text accompanying these early pictures comes from the reminiscences of Wittgenstein’s oldest sister, Hermine, who describes her parents, their houses, her siblings, and also the family’s close relations with the leading artists of the time. These emerged principally through Karl’s generous patronage of the visual arts. Gustav Klimt, the leading artist of the Secession Movement, who was commissioned to paint the wedding portrait of Wittgenstein’s youngest sister, Margarethe (“Gretl”), called Karl his “Minister of Fine Art.”

Unlike the house in which he himself had grown up, however, the home Karl created with Poldy was one marked by tragedy as well as comfort and high culture. Ludwig’s two oldest brothers, Hans and Rudi, both committed suicide during his childhood. When Ludwig was thirteen, Hans, who had, like his father, fled to America, disappeared from a boat in Chesapeake Bay and was assumed to have taken his own life. Rudi’s suicide was reported in sensational fashion two years later by the Berliner Tageszeitung, which related how Rudi, who had come to Berlin seeking a career in drama, had gone into a bar and ordered two drinks (in fact these were two glasses of milk). After sitting by himself for a while, he asked the piano player to play a love song called “Verlassen bin ich” (“I Am Lost”) and, as the music played, took cyanide and died. This newspaper report is used by Nedo to accompany a photograph of Rudi with his head in his hand, looking anxious and contemplative. The same page has a more conventional profile portrait of Hans, showing him to be exceptionally handsome and well groomed.

In 1906, two years after Rudi’s death, Wittgenstein’s life was affected by yet another suicide when the physicist Ludwig Boltzmann, with whom he had wanted to study, killed himself. Exactly why Wittgenstein wanted to study with Boltzmann is not known, though when, in 1931, he compiled a list of those who had influenced him, Boltzmann’s name was the first on it, followed by those of Hertz, Schopenhauer, Frege, Russell, Kraus, Loos, Weininger, Spengler, and Sraffa. Given the restraints imposed upon Nedo by his chosen method of composition, he can shed little light on this question. Indeed, from here onward the gap between what this book can offer and what is required for an adequate introduction to Wittgenstein’s work gets wider and wider. To describe and explain the influences, obsessions, and ideas that drive a great thinker’s intellectual development, a collection of pictures can have only very limited success.

From the time of Boltzmann’s death until Wittgenstein’s first philosophical work, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, appeared in 1921, the emphasis in a book that has any pretensions to be a guide to his thought ought to be on giving the reader some insight into what philosophical questions he was concerned with and how he went about addressing them. Pictures of the places Wittgenstein lived and the people he met during this period do very little to accomplish this. What we have rather are fascinating evocations of Wittgenstein’s life during these years, together with a sample of the texts that one would need to study to understand the evolution of his philosophical thinking. But this does not add up to an introduction to his philosophy. On the contrary, the people who will get most out of looking at the pictures and texts that Nedo has assembled are those who already know something about Wittgenstein’s work.

For example, after spending two years in Berlin, Wittgenstein went to Manchester to concentrate specifically on aeronautical engineering. As part of these studies, he designed and patented an aircraft engine. The first page of the patent application and some of the associated drawings are reproduced here, but the extract from Boltzmann’s 1905 work Populäre Schriften that is placed alongside those drawings sheds no light whatever on Wittgenstein’s design. Likewise, in one of Nedo’s rare editorial interventions, we are told very briefly that Wittgenstein’s work on this design aroused in him an interest in the foundations of mathematics that led him to study the works of Gottlob Frege and Bertrand Russell and then to study with Russell at Cambridge; but, without some attempt to summarize the ideas of Frege and Russell, this information is of little help in understanding the direction of Wittgenstein’s thought. And reproducing the title page of Russell and Whitehead’s Principia Mathematica does nothing to help.

There are some wonderful pictures here of pre–World War I Cambridge, including a marvelous shot of students in straw hats lolling about in boats on the river Cam, among whom are John Maynard Keynes and Rupert Brooke, but generally, the book becomes visually rather unexciting at this point, with too many photographs of books and typescripts and too little explanation of their content.

In 1913, Wittgenstein left Cambridge to live alone in a remote part of Norway, where he built a house for himself on the side of a fjord. Nedo has found some pictures of the house that speak loudly and clearly of its majestic isolation, but one would never guess from these pages that for the rest of his life Wittgenstein considered the year 1913–1914 to be philosophically the most creative year of his life. Still less would one gather why. During that year, Wittgenstein produced two sets of notes on logic that are the earliest philosophical writings of his to survive and that show that much of what he would put into Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus was already clear in mind in the summer of 1914, when, in the first few days of the Great War, he made the decision to volunteer for the Austro-Hungarian army. (“Wittgenstein,” Bertrand Russell once quipped, “though a logician, was at once a patriot and a pacifist.”)

The years Wittgenstein spent as a soldier—first behind the lines in Galicia, then at the Eastern Front, and finally at the Italian Front, where, at the end of the war, he was taken prisoner—are well served in this book, which contains pictures of his military ID card, all the theaters of war in which he was engaged, and, finally, bedraggled prisoners in an Italian POW camp. There are also some powerful images of Wittgenstein’s brother Kurt, who at the end of war became the third brother to commit suicide when he shot himself after the men under his command had deserted. The last war-related picture is perhaps the most poignant. It shows a page from Wittgenstein’s photo album on which is stuck a tiny photograph of a moving scene at Palais Kaunitz: a line of injured soldiers waiting their turn to shake Aunt Clara’s hand as they make their stumbling way out of her grand house, which, for the duration of the war, had served as a military convalescent home.

After the war, Wittgenstein saw through the publication of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus and then abandoned philosophy, all problems of which he considered himself to have solved. His conviction on this point rested on his view that all philosophical problems arose out of misconceptions about the nature of logic and language. In giving clear and correct answers to the questions “what is logic?” and “what is a proposition?,” then, he regarded himself as having answered once and for all philosophical questions. He thus gave up philosophy in favor of teaching in elementary schools in Lower Austria. Between 1922 and 1926 Wittgenstein taught in three different rural villages and was regarded as rather weird in all of them.

There are some wonderful pictures here of Wittgenstein with the children—mostly the sons and daughters of farmers—whom he taught, but there is very little indication of the tension that existed between him and the villagers, nor of how disastrous this period of his life was. Forced to leave teaching, he returned to Vienna, where for a few years he adopted an entirely unexpected profession: he became an architect, albeit one with only one house to his name, a starkly modernist house that he designed for his sister Margarethe. Here the book comes into its own with sumptuous pictures of the inside and the outside of the house and revealing close-ups of its fixtures and fittings.

In 1929, Wittgenstein returned to Cambridge and from then until his death in 1951, he developed an entirely new method of philosophizing that is in my opinion, and that of most people who admire his work, his greatest achievement. Just as in his early work, Wittgenstein understood philosophical problems to arise through linguistic misunderstandings, but now he offers a more profound and more plausible analysis of the kind of misunderstandings that result in philosophical confusion. For example, the tendency to regard the meaning of a word as the object for which it stands, though relatively harmless in connection with words like “table,” “chair,” etc., results in much misguided philosophical theorizing when applied to words like “mind” or “number.” Indeed, in his new method of doing philosophy Wittgenstein abandoned theorizing altogether.

Central to this new method is the emphasis he gives to seeing things differently and the associated notion of “family resemblances.” In the most interesting and important pages of this book (and the most significant respect in which it improves on the earlier book), Nedo reproduces a composite photograph made up of four portraits of Wittgenstein and his three sisters (see illustration on page 56). At first it looks like a picture of just a single person, but then one notices details of the various component photographs. Around the neck, for example, one sees a strange assortment of accessories: Helene’s scarf, Margarethe’s necklace, and the ghost of Ludwig’s open-necked shirt. And yet the eyes, the nose, and the mouth look like they belong to the same person, enabling one to see directly the very strong family resemblances that existed between these four siblings. The notion of “family resemblances” is crucial to Wittgenstein’s later philosophy, and in these pages Nedo does a decent job of explaining why.

This book may not be the “excellent introduction” to Wittgenstein’s thought that it advertises itself as being, but as well as being an extraordinarily effec-tive evocation of Wittgenstein’s life, it also offers, in a uniquely appropriate way, an insight into the crucial role that seeing and showing play in Wittgenstein’s worldview.