The work of Philip Roth, if we are to believe him, has been completed. He has retired from the business of novel-writing; there will be no more alter egos, no more splitting or doubling. As Dr. Spielvogel, in the punch line to Portnoy’s Complaint, asks: “Now vee may perhaps to begin. Yes?”

This fixity was the “precondition” for the New Yorker writer Claudia Roth Pierpont’s Roth Unbound: A Writer and His Books, which could only have been written “with the full arc of Roth’s work completed.” She believes, then, that there is an arc to the work, and that we can only now—now that it terminates—trace that arc properly. This might read as introductory biographical boilerplate, but in Roth’s case it makes a real claim. Roth’s work resists easy explanation; few other writers have had careers in which, for example, a rather traditional realist novel like American Pastoral (1997) follows immediately upon one full of obscene fulminations like Sabbath’s Theater (1995). Other critics have defended the coherence of Roth’s work without reference to all of the books—Ross Posnock in Philip Roth’s Rude Truth (2006) wrote with critical insight about all but the few final volumes—but Pierpont takes this completeness as an invitation to say something definitive.

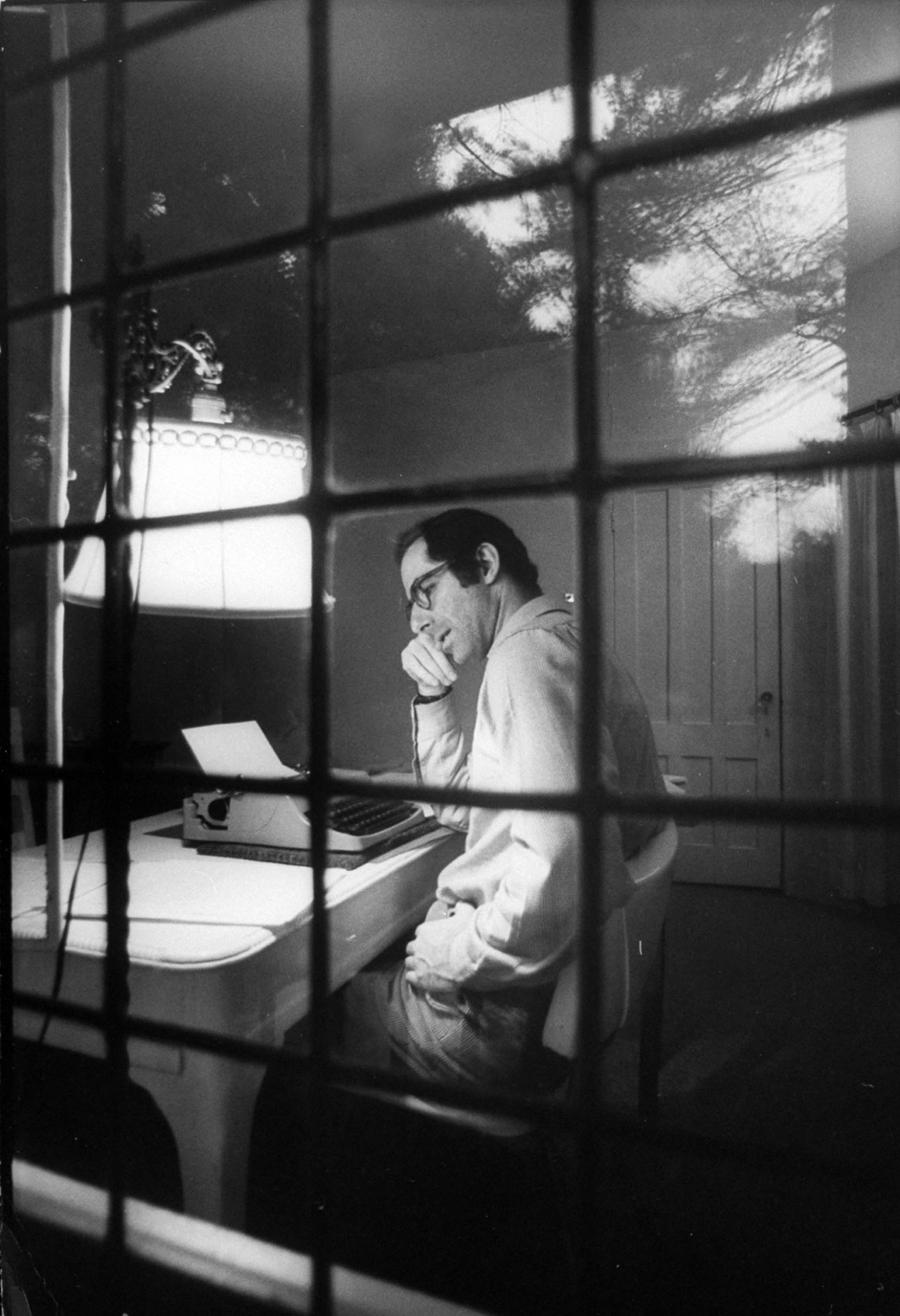

This advances an argument with Roth himself. In his 1984 interview with The Paris Review, Roth resisted linear metaphors to describe his career: “It’s all one book you write anyway. At night you dream six dreams. But are they six dreams? One dream prefigures or anticipates the next, or somehow concludes what hasn’t yet even been fully dreamed.” A critic might well respond that to dream dreams and to interpret them are two different things. But the second precondition of Pierpont’s book, beyond completeness, was access to the dreamer. Now that he no longer spends most days in a remote Connecticut hideout writing novels, he at last has the time to kibitz. Pierpont’s book has emerged from some eight years of informal friendly conversation with Roth. His presence accounts for what she calls the book’s “hybrid form.”

By this she means that her book is neither a “conventional biography” with “names and dates” nor a sober critical study. For the former we’ll have to wait for the volume Blake Bailey is preparing. Pierpont discusses Roth’s first wife and a few of his longtime girlfriends, but she mostly keeps his secrets to herself. On the relationship of Roth’s life to the story of the suicide at the center of The Humbling (2009), for example, she writes that

while it’s true that Roth did have a torrid affair in these years with a forty-year-old former lesbian, he survived it perfectly well, and they are friends today. It’s also true that he began to think about having a child and consulted a doctor about genetic feasibility—but this was a little later, and with a different lover.

The book’s tone on these matters is withholding. Pierpont is protective of her friend and his privacy.

It’s not straight criticism either. Pierpont proceeds chronologically, as an arc requires. There’s a chapter for each book or two, along with background information, and she is unabashed in her admiration. Her treatment of The Dying Animal (2001) is characteristic. She begins by remarking that, at age sixty-seven, one might expect a novelist to slow down; Roth, however, “expanded his range and power as he aged.” Roth’s last challenge had been to learn how to write such “big, complicated books” as The Counterlife, and with The Dying Animal he wanted to “do something lean and direct.” He asked Saul Bellow, with whom he’d by then become close, for advice, but Bellow only laughed.

The Dying Animal is a sexually explicit book—Roth “has lost none of his desire to shock”—but Pierpont explains the sex as metaphorical. It’s not about the act itself but about “the ways we find to accommodate its disruptive power—and, indeed, about personal freedom.” Pierpont catalogs the negative reviews, most of which dilated on the misogyny of Roth’s antihero, David Kepesh, now resurrected for a coda to an earlier pair of books. These critics of this “blunt and unbeguiling” novel had a point, Pierpont thinks, but they make the classic mistake of Roth criticism: the identification of his views with those of his characters. “But it’s one thing to say that Kepesh is limited or unlikable and another to say that he’s unreal, or doesn’t represent something real.”

Roth himself doesn’t come down one way or another. As Pierpont puts it, “The upshot seems to be that marriage is one form of hell, but the post-revolutionary sexual situation can be another.” It’s a cogent reading of the book. Pierpont is ultimately more interested, however, in how the books point back to the life. She closes the chapter with an aperçu from Roth. Does he believe in a happy marriage? “Yes, and some people play the violin like Isaac Stern. But it’s rare.”

Advertisement

Pierpont’s hybrid form results from her attempt to couple the completeness of the works—though she ultimately predicts he’ll write novels again—and her access to the man behind them. Completeness is necessarily a matter of how each book fits in with all the other books; it allows her to map their trajectory. Access is a matter of how each book fits with the life of the writer; it allows her to correct the record—to defend Roth against accusations of misogyny and anti-Semitism, and protect him from how badly he’s been read—by distinguishing between Roth’s characters and their creator. This reconciliation of art and life makes for a difficult project, especially because Roth insists he’s been boring. “The uneventfulness of my biography would make Beckett’s The Unnameable read like Dickens.” It is precisely such uneventfulness, he thinks, that has made room for the eventfulness of the books.

Pierpont twice refers to a line of Flaubert’s that Roth admires: “Be regular and orderly in your life like a bourgeois, so that you may be violent and original in your work.” She initially claims that her solution to the problem will be to follow Roth in distinguishing not between art and life but between written and unwritten lives. What Roth seems to mean is that the written life is accountable within a formal system—the practice of writing novels—the way the unwritten life, with its inconsistency and disorder, is not. A few sentences later Pierpont reverses herself, redrawing once more the problem-filled distinction. “This book, then, is about the life of Philip Roth’s art and, inevitably, the art of his life.” It’s a lot of pressure to put on both.

It is this idea of “the art of his life,” beyond details of Roth’s indiscretions, around which Pierpont’s protectiveness gathers. Her “hybrid form” promises that the work and the life might be seamlessly integrated; she writes as if the greatness of this artist depended on that very unity. It’s easy to understand why Pierpont might feel this way. We might believe, for example, that Nabokov’s jewel-box novels were the fruits of a disciplined life. The reaction to J. Michael Lennon’s recent biography of Norman Mailer has been that the energy Mailer put into his extraordinary life might otherwise have gone into his uneven books.

About Roth one hopes otherwise. His best work has tremendous vitality, a vitality we can only suspect spills over from the life, and spills back into it. Since the 1993 breakup of his second marriage, to the actress Claire Bloom, Roth has cultivated the image of the woodsy recluse. It’s an image Pierpont remains invested in—she praises the “unrelenting work ethic” that tethers Roth to his desk each morning and most evenings—but one she seeks to complicate. In his cameo appearances as himself, Roth comes across as more of a character from the work than an authority on the life. He cuts a folksy, avuncular, self-deprecating figure of hail-fellow-well-met Yiddishkeit.

It is important to Pierpont that we understand that this ultimate self- satisfaction has been hard-won. When we first meet Pierpont’s Roth, he’s living in the East Village, awaiting the 1959 publication in The New Yorker of the story “Defender of the Faith,” in which a Jewish combat hero must decide how to treat a coreligionist draftee who petitions for special favors. Pierpont glosses the story in a few sentences about conflicting loyalties. The surface drama, which she concentrates on, is between loyalty to tribe and loyalty to nation, but the more profound issue is between alternate interpretations of loyalty to tribe: Nathan Marx, the sergeant, clearly believes that the Jewishly loyal thing to do is to treat his charge as he does the other conscripts.

Roth himself considered it a faithful story—faithful to the difficult negotiations of dual allegiance to which American Jews brought great effort. He was thus “blindsided” by the accusations of “informing”—that is, airing run-of-the-mill Jewish venality before a wide mixed audience—leveled at him by some furious rabbis. The chapter closes with Roth at a now-famous 1962 symposium at Yeshiva University. The moderator’s first question established the evening’s hectoring tone: “Mr. Roth, would you write the same stories you’ve written if you were living in Nazi Germany?”

In Pierpont’s book, a beleaguered Roth is “barely able to respond coherently.” In David Remnick’s 2000 New Yorker profile of Roth, the scene is somewhat different: “Over and over, Roth answered, ‘But we live in the opposite of Nazi Germany!’ And he got nowhere.” In Pierpont’s dramaturgy a weak Roth tries to collect himself with new resolve: “In the safety of the Stage Delicatessen, over a pastrami sandwich, he vowed, ‘I’ll never write about Jews again.’” He basically avoided Jews for the next two books, Letting Go (1962) and When She Was Good (1967). Pierpont’s pattern has taken shape: there’s enough about a book to provide a setting for a decisive moment in the life, and then enough of the consequences for the life to watch it feed back into the work.

Advertisement

As Roth’s fame grows—with Portnoy’s Complaint (1969) he becomes a household name—it becomes easier for Pierpont to convince us that Roth has led a life so noteworthy as to be commensurable with his imaginative production. We get, in turn, a lot of Roth’s melodramatic relations with women. His marriage to the troubled Maggie Williams—the story that became My Life as a Man (1974)—“may have been the most painfully destructive and lastingly influential literary marriage since Scott and Zelda.” We get Roth on a date with Jackie Kennedy—“Do you want to come upstairs? Oh, of course you do”—which, much later, went straight into Zuckerman Unbound. When Roth lives part-time in London with Bloom in the 1980s, there’s Roth in a tumult over Israeli politics with Harold Pinter; Alfred Brendel, seated nearby, worries they might fall on his hands.

Pierpont’s effort to give us a more complicated, flashier Roth makes for a diverting read. But it also derives from the work itself, which has long been preoccupied with questions of fame. How does fame change how one understands loyalty and betrayal? A Jewish writer who wanted to be understood as more than merely a Jewish writer had, prior to Roth, two options: not to write about Jews at all, or, like Bellow, to write about Jews and get famous—to show that by burrowing into particularism one might discover a counterintuitive route to universality; this was an attempt to show that clannishness need not destroy broader affiliations, and can even shore them up.

Pierpont’s Roth is committed to both rien que travailler and dinner parties alongside Frank Sinatra. She does not make the gossip-column mistake of blurring together the life and the work, of identifying Roth with Alexander Portnoy. But she doesn’t seal Roth away from Portnoy, as she might, by declaring the relationship of art to life to be unknowable and uninteresting. She needs each around to defend the other. She strains to have it both ways: Roth’s life resembles his alter ego Nathan Zuckerman’s only when it suits her purposes, which, without making the distinction clear, alternate between Roth’s invincibility and his vulnerability.

Roth is at his most vulnerable when charged with misogyny, and Pierpont devotes much of her book to refuting that charge. She makes a convincing literary case for his best heroines, for female characters as strong and complex as his male heroes: When She Was Good’s Lucy Nelson, Maria Freshfield in The Counterlife, Faunia Farley in The Human Stain. But she only undermines her position when she overreaches toward counterexamples from Roth’s life. “He considers himself a man who loves women, and he counts many women among his close and lifelong friends.” Lines like these sound merely dutiful.

Pierpont’s profiles of women writers—collected as Passionate Minds (2000)—are at once sympathetic and sharply ironic. Roth Unbound’s emphatic sincerity seems to stem from Pierpont’s worry that Roth’s own irony has proven too weak a weapon. This is plain in even minor ways. She is always anxiously stepping on his punch lines, as if he might embarrass himself. At one point, at a dinner party, someone asked the obvious question about their possible relation. (They are unrelated.) “Roth,” she writes, “turned to me with a look of mild horror and wary recognition: ‘Did I used to be married to you?!’ Fortunately, a moment of reflection proved that this was not the case.”

If it were just a matter of Pierpont’s occasional smothering, then what can you do? Nobody ought to be blamed for loving Philip Roth. But in her alacrity to provide for him as expansive and triumphant a life as possible, Pierpont inadvertently diminishes his real, inestimable achievements. She has muffled Roth the struggling adult in favor of Roth the struggling adolescent, who requires praise and security as he blunders, both potent and helpless, toward autonomy. Roth, like a perpetual hero of a serial bildungsroman, is always getting bigger, becoming both more serious and more free.

In the early 1970s, she writes, Roth spent time in Prague; in the 1980s, he visited Israel regularly. Though “Roth had always thrived on moral engagement,” she suggests that he felt historically belated, having missed out on the real “heyday” of “no-nonsense anti-Semitism” for the narcissistic idyll of a frictionless American adolescence. In Prague, however, he met with dissident writers: “As far from Newark as Roth could get, he found another living moral subject.” When Roth returned to New York, he collected money to send to his friends in the Eastern Bloc, and later edited a series of books by Eastern European writers. He traveled to Prague frequently enough to be tailed by the Czech secret police. One night, his friend the writer Ivan Klíma was arrested and interrogated about Roth’s visits. “Don’t you read his books?” Klíma asked. “He comes for the girls.”

This is a good anecdote. It’s also exactly the sort of thing that might happen in a Roth book. The serious joke here, for Pierpont, is that Roth was overseas partly because he was sick of being overidentifed with Portnoyan priapism, sick of being “in his own head.” It is a neat interlacing of art and life to credit to those trips the stylistic innovations of The Prague Orgy (1985) and The Counterlife (1987).

As Pierpont sees it, Roth sought a chance to play for higher stakes, and it paid off both morally and professionally. Clearly he did much to help Eastern European writers. But these books also question the very notion of higher stakes. The staggering feat of The Counterlife is the profusion of mixed motives Roth manages. Nathan Zuckerman criticizes his brother, Henry, a stifled dentist, for using Israel as the one morally incontestable way to abandon his family. Henry turns around to criticize Nathan for using Israel as a way to flee well-trodden Newark ground.

Nothing is ever as clear or necessary for Roth’s characters as they are for Pierpont’s Roth. If Roth’s characters, with their “taste for perpetual crisis,” are generally in a muddle, Pierpont’s Roth is always emerging from one in triumph. His art, it is true, grew more inventive and wide-ranging; by Pierpont’s logic, the life had to follow suit. Art and life are here yoked to each other in discontinuity, and Pierpont is determined to bestow upon Roth the transformation Roth denies his characters. Nearly every book is identified as some kind of inflection point, both for Roth’s work and for his life. With Portnoy’s Complaint, “Roth himself achieved the freedom that his hapless hero could not win; the book’s shameless, taboo-squelching language was liberating for both the author and his readers.”

My Life as a Man, despite its “technical displays,” shows an unfortunate “lack of freedom.” The Ghost Writer (1979) was a “breakthrough” en route to the Zuckerman novels of the 1980s, of which The Counterlife is “an exhilarating culmination of the theme: a book about transformation, about what happens when people finally break free. Roth knew what that felt like.” After The Counterlife, “his freedom as a writer just seemed to keep growing.”

This takes us just halfway through Roth’s career, before the further breakthroughs of Sabbath’s Theater—“a development he attributes to the unprecedented freedom that he felt in writing it”—and American Pastoral. I Married a Communist (1998) is marred by Roth’s anger with Claire Bloom: “here the desire for revenge seems to contract Roth’s novelistic freedom.” In 330 pages, variants of the word “free” appear almost a hundred times.

Pierpont has chosen the wrong vocabulary to unify Roth’s life and his work. Roth’s characters act within a dialectic of enslavement and liberation. Roth himself acts within a network of sustaining loyalties. When narrating the story of his own life in The Facts (1988), Roth only rarely uses the language of freedom, and when he does he reserves it for referring to his “written life”: in the late 1960s he felt “liberated from an apprentice’s literary models” when he began to shake off the overwhelming presence in his life of James and Flaubert in order to make room for Kafka and Gogol. The fantastic language of personal liberation belongs to Nathan Zuckerman, who, in a postscript, advises Roth that his memoir is too even-keeled to publish. The single discontinuity with which Roth’s memoir grapples is the surprising death in an auto accident of his first wife, after years of enervating legal battles; the irony of this otherwise pointedly unironic text is that his release from that relationship was not a matter of romantic heroism but of sheer contingency.

When Roth talks about the inflection points in his life and career, he doesn’t identify eruptions of freedom. He describes painstaking renovations of old allegiances to accommodate new ones. It is a matter of dreamlike shift, not the vaulting arc Pierpont wants to portray: his achievement has been an intricate braiding of supportive ties, not a glorious slashing of restrictive ones. His most continuous theme is the fantasy of discontinuity, the deluded idea that we might gain freedom from all loyalties. In a 1969 letter to Diana Trilling, he wrote:

That a passion for freedom—chiefly from the bondage of a heart- breaking past—plunges Lucy Nelson [of When She Was Good] into a bondage more gruesome and ultimately insupportable is the pathetic and ugly irony on which the novel turns. I wonder if that might not also describe what befalls the protagonist of Portnoy’s Complaint.

For Roth, little good can come of real treachery; the things that seem at first like betrayals are often just unprecedented ways of making room for multiple loyalties. As he said in the essay he wrote in the wake of the 1963 Yeshiva colloquium, “Writing about Jews”:

At times they see wickedness where I myself had seen energy or courage or spontaneity; they are ashamed of what I see no reason to be ashamed of, and defensiveness when there is no cause for defense.

For Pierpont, Roth was scared away from the Jews of Goodbye, Columbus and into the goyim of Letting Go by the Yeshiva incident, only to roar back on his own Jewish terms with Portnoy’s Complaint. But it is far more plausible that Roth saw only his abiding dream of creating something in which Flaubert, James, Chekhov, Bellow, Malamud, and Herman Roth would all recognize themselves.

For Pierpont, the fact of Roth’s completeness offered an opportunity to celebrate his liberation, his great leaps forward. But it might just as easily be an opportunity to celebrate his loyalty, the lifelong elaboration of the comic Jewish-American embrace we now take for granted. Her access to Roth gave Pierpont the chance to free him from his entanglements, with Kepesh, Zuckerman, and Portnoy. Instead she leaves him trapped.

This Issue

December 19, 2013

Mike

An American Romantic

Gazing at Love