In the course of three days in August 1991, during the failed putsch against Gorbachev, the decaying Soviet empire tottered and began to collapse. Some friends and I found ourselves on Lubianskaya Square, across from the headquarters of the fearsome, mighty KGB. A huge crowd was preparing to topple the symbol of that sinister institution—the statue of its founder, Dzerzhinsky, “Iron Felix” as his Bolshevik comrades-in-arms called him. A few daredevils had scaled the monument and wrapped cables around its neck, and a group was pulling on them to ever louder shouts and cries from the assembled throng.

Suddenly, a Yeltsin associate with a megaphone appeared out of the blue and directed everyone to hold off, because, he said, when the bronze statue fell, “its head might crash through the pavement and damage important underground communications.” The man said that a crane was already on its way to remove Dzerzhinsky from the pedestal without any damaging side effects. The revolutionary crowd waited for this crane a good two hours, keeping its spirits up with shouts of “Down with the KGB!”

Doubts about the success of the coming anti-Soviet revolution first stirred in me during those two hours. I tried to imagine the Parisian crowd, on May 16, 1871, waiting politely for an architect and workers to remove the Vendôme Column. And I laughed. The crane finally arrived; Dzerzhinsky was taken down, placed on a truck, and driven away. People ran alongside and spat on him. Since then he has been on view in the park of dismantled Soviet monuments next to the New Tretiakov Gallery. Not long ago, a member of the Duma presented a resolution to return the monument to its former location. Given events currently taking place in our country, it’s quite likely that this symbol of Bolshevik terror will return to Lubianskaya Square.

The swift dismantling of remaining Soviet monuments recently in Ukraine caused me to remember the Dzerzhinsky episode. Dozens of statues of Lenin fell in Ukrainian cities; no one in the opposition asked people to treat them “in a civilized manner,” because in this case a “polite” dismantling could mean only one thing—conserving a potent symbol of Soviet power. “Dzhugashvili [Stalin] is there, preserved in a jar,” as the poet Joseph Brodsky wrote in 1968. This jar is the people’s memory, its collective unconscious.

In 2014, Lenins were felled in Ukraine and were allowed to collapse. No one tried to preserve them. This “Leninfall” took place during the brutal confrontation on Kiev’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square), when Viktor Yanukovych’s power also collapsed, demonstrating that a genuine anti-Soviet revolution had finally occurred in Ukraine. No real revolution has happened in Russia. Lenin, Stalin, and their bloody associates still repose on Red Square, and hundreds of statues still stand, not only on Russia’s squares and plazas, but in the minds of its citizens.

The fury of our politicians’ and bureaucrats’ response to the mass destruction of Soviet idols in Ukraine is revealing. You might think, why pity symbols of the past? But Russian bureaucrats understand that their beloved Homo sovieticus crumbled along with Lenin. “They are destroying monuments to Lenin because he personifies Russia!” one politician exclaimed. Yes: Soviet Russia and the USSR, the ruthless empire, built by Stalin, that enslaved whole peoples, created a devastating famine in Ukraine, and carried out purges and mass repressions. The recent Ukrainian revolution was indeed directed against the heirs of that empire—Putin and Yanukovych. It is telling that pro-Russian demonstrations in Crimea and eastern parts of Ukraine invariably took place next to statues of Lenin.

Unfortunately, what happened in recent weeks in Ukraine did not happen in Russia in 1991. Yeltsin’s revolution ended up being “velvet”: it did not bury the Soviet past and did not pass judgment on its crimes, as was the case in Germany after World War II. All those Party functionaries who became instant “democrats” simply shoved the Soviet corpse into a corner and covered it with sawdust. “It will rot on its own!” they said.

Alas, it didn’t. In recent opinion polls, almost half of those surveyed consider Stalin to have been a “good leader.” In the new interpretation of history, Stalin is seen as an “effective manager,” and the purges are characterized as a rotation of cadres necessary for the modernization of the USSR. The Soviet Union may have collapsed geographically and economically, but ideologically it survives in the hearts of millions of Homo sovieticus. The Soviet mentality turned out to be tenacious; it adapted to the wild capitalism of the 1990s and began to mutate in the post-Soviet state. That tenacity is what preserved a pyramidal system of power that goes back as far as Ivan the Terrible and was strengthened by Stalin.

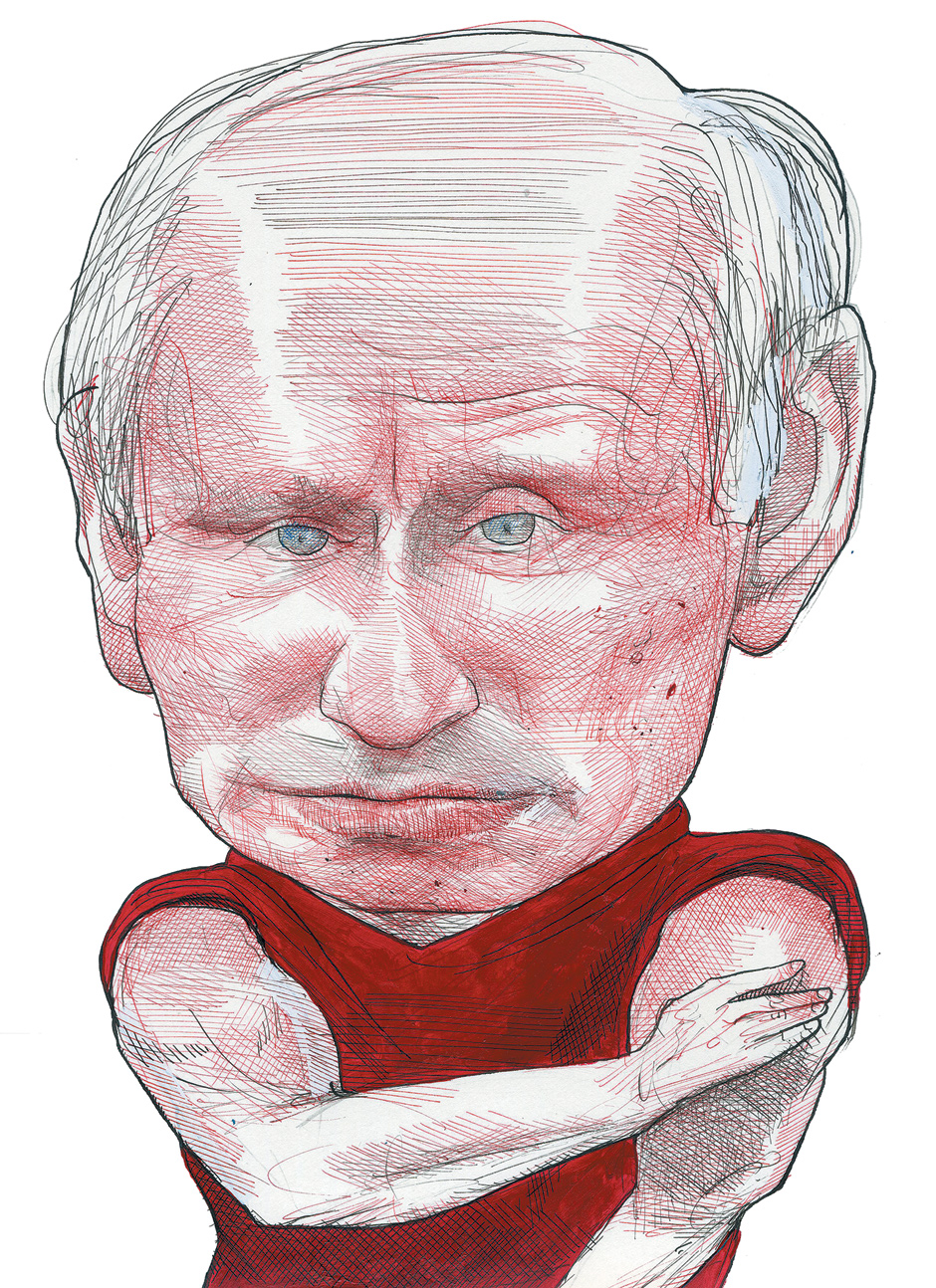

Yeltsin, who was tired after climbing to the top of the pyramid, left the structure completely undisturbed, but brought an heir along with him: Putin, who immediately informed the population that he viewed the collapse of the USSR as a geopolitical catastrophe. He also quoted the conservative Alexander III, who believed that Russia had only two allies: the army and the navy. The machine of the Russian state moved backward, into the past, becoming more and more Soviet every year.

Advertisement

In my view, this fifteen-year journey back to the USSR under the leadership of a former KGB lieutenant colonel has shown the world the vicious nature and archaic underpinnings of the Russian state’s “vertical power” structure, more than any “great and terrible” Putin. With a monarchical structure such as this, the country automatically becomes hostage to the psychosomatic quirks of its leader. All of his fears, passions, weaknesses, and complexes become state policy. If he is paranoid, the whole country must fear enemies and spies; if he has insomnia, all the ministries must work at night; if he’s a teetotaler, everyone must stop drinking; if he’s a drunk—everyone should booze it up; if he doesn’t like America, which his beloved KGB fought against, the whole population must dislike the United States. A country such as this cannot have a predictable, stable future; gradual development is extraordinarily difficult.

Unpredictability has always been Russia’s calling card, but since the Ukrainian events, it has grown to unprecedented levels: no one knows what will happen to our country in a month, in a week, or the day after tomorrow. I think that even Putin doesn’t know; he is now hostage to his own strategy of playing “bad guy” to the West. The wheel of unpredictability has been spun; the rules of the game have been set. The trump card of Putin’s first decade was stability, which he used to destroy opposition and drive it underground. Now he’s playing the capricious, unpredictable Queen of Spades. This card will beat any ace.

The phrase “Russia in the Shadows,” as H.G. Wells titled his book on Bolshevik Russia, has been on the minds of many Russian citizens lately. One hears things like “The ground trembled beneath us!” all the time now. The huge iceberg Russia, frozen by the Putin regime, cracked after the events in Crimea; it has split from the European world, and sailed off into the unknown. No one knows what will happen to the country now, into which seas or swamps it will drift. At such times, it’s better to rely on intuition than common sense. My most perceptive compatriots feel that when Russia seized Crimea from Ukraine, it bit off more than it will be able to chew or digest. The state’s teeth are not what they were, and for that matter, its stomach doesn’t work as it once did.

If you compare the post-Soviet bear to the Soviet one, the only thing they have in common is the imperial roar. However, the post-Soviet bear is teeming with corrupt parasites that infected it during the 1990s, and have multiplied exponentially in the last decade. They are consuming the bear from within. Some might mistake their fevered movement under the bear’s hide for the working of powerful muscles. But in truth, it’s an illusion. There are no muscles, the bear’s teeth have worn down, and its brain is buffeted by the random firing of contradictory neurological impulses: “Get rich!” “Modernize!” “Steal!” “Pray!” “Build Great Mother Russia!” “Resurrect the USSR!” “Beware of the West!” “Invest in Western real estate!” “Keep your savings in dollars and euros!” “Vacation in Courchevel!” “Be patriotic!” “Search and destroy the enemies within!”

On the subject of enemies within… In his speech about the accession of Crimea to Russia, President Putin mentioned a “fifth column” and “national traitors” who are supposedly preventing Russia from moving victoriously forward. As many have already remarked, the expression “national traitor” comes from Mein Kampf. These words, spoken by the head of state, caused a great deal of alarm in many Russian citizens. The intelligentsia went into shock. The Russian intelligentsia, it should be said, is now especially alarmed. While the people shout “Crimea is ours!” at government demonstrations, our intelligentsia carries on its usual defeatist conversations:

“There will be purges, like in ’37…”

“He won’t stop at Ukraine…”

“Looks like it’s time to leave the country…”

“You just can’t watch TV anymore—all they show is propaganda…”

“The West will turn its back on us…”

Advertisement

“Russia will be a pariah…”

“It’s all making me really depressed…”

“Samizdat and the underground will be back again…”

I confess that conversations like these make me sicker than the annexation of Crimea. I want to say to my fellow intelligenty: “Friends, over the last fifteen years comrade Putin has become what he is now only because of our own weakness.”

Ukraine has taught Russia a lesson in loving freedom and refusing to tolerate a base, thieving regime. Ukraine found the strength to break away from the post-Soviet iceberg and sail toward Europe. Maidan—Independence Square—showed the world what a people can accomplish when it so desires. But when I watched the reports from Kiev, I could not imagine anything similar in today’s Moscow. It is difficult to imagine Muscovites fighting the OMON special forces day and night on Red Square and facing snipers’ bullets with wooden shields. For that to happen, something must change not only in the surrounding environment, but in people’s heads. Will it?

We shouldn’t have waited for the crane to arrive at Lubianskaya Square in August 1991. We should have toppled the iron idol even if its head did crash through the pavement and damage “important underground communications.”

We would live in a different country now.

How important it is, as it turns out, to let the past collapse at the right time…

—Translated from the Russian by Jamey Gambrell

This Issue

May 8, 2014

The New Gilded Age

The Charms of John Updike