“Art is long,” wrote the poet Randall Jarrell, “and critics are the insects of a day.” Which is another way of saying that writing book reviews can make you feel like a manic-depressive housefly. You buzz and bang your head on the window out of sheer guilt and frustration. Siri Hustvedt’s novel The Blazing World is liable to induce a particularly twitchy and abject version of housefly headbanging. The windows are shut fast; the book a distinctly mixed bag; a claustrophobic critic feels obliged to air her doubts. But then, along with the guilt, a familiar neurosis sets in. Huge and bestudded though they are, can one’s multiple convex eyes even be trusted?

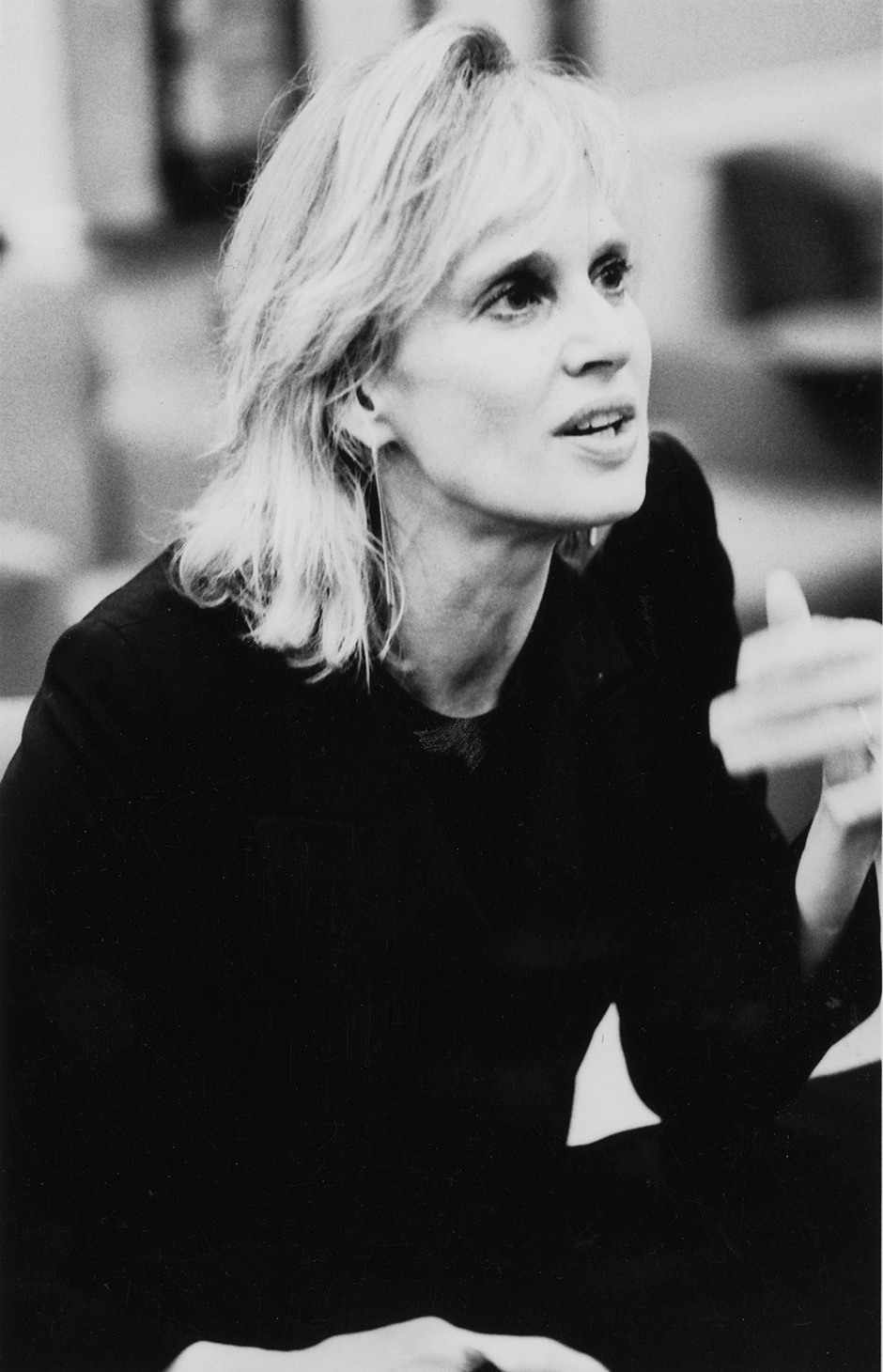

One is forced to ask because ever since The Blindfold (1992)—hailed by the late David Foster Wallace as “very powerful and awfully smart and well-crafted, a clear bright sign that the feminist and postmodern traditions are far from exhausted”—to The Enchantment of Lily Dahl (1996), What I Loved (2003), The Sorrows of an American (2008), and The Summer Without Men (2011), the judgments about Hustvedt’s fiction have been loud and laudatory. “One of our finest novelists,” declares Oliver Sacks. A writer—says Salman Rushdie—of “sexy…indelibly memorable fiction.” “A contemporary Jane Austen,” writes a UK critic; “densely brilliant…terrifyingly clever.”

Adding to the consternation: Hustvedt isn’t only a novelist. In addition to her fiction, she’s published three volumes of much-admired art and literary criticism, plus any number of squibs, reviews, and off-the-cuff autobiographical forays of charm and candor. (One is about how it felt to wear a corset for eight days as a movie extra for a film of James’s Washington Square.) In 2010 she published the weirdly gripping neuro-memoir The Shaking Woman; or, A History of My Nerves, in which she explored—in full-on brain-science-mystery mode—her struggles in early middle age with an onslaught of terrifying and seemingly inexplicable quasi-epileptic seizures. (Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio went bananas over it.)

Hustvedt fans will no doubt greet The Blazing World—already being promoted as a masterpiece, if not the masterpiece of Hustvedt’s career—with relief and anticipation. The writing would appear to go on, vividly unencumbered, its author’s capacious reserves of intelligence and creative energy unimpaired.

Not unexpectedly, Hustvedt is also a serious feminist, much praised for her thoughtful fictional renderings of women’s lives, especially as lived among the urban, college-educated, Kindle-owning, heterosexual middle classes. (The Blazing World, Katie Roiphe suggests, is “feminism in the tradition of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, or Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own: richly complex, densely psychological, dazzlingly nuanced.”) Never having met Hustvedt—she’s from Minnesota and went to St. Olaf’s, where her father was a celebrated professor of Norwegian—I imagine her as a sort of sturdy lady-Viking crossed with George Eliot: deeply cultured, an unabashed exponent of the higher seriousness, but one whose bluestocking worldview has also been shaped by a practical, down-to-earth, Joan Mondale–meets–Pippi Longstocking female advocacy. It’s an appealing package. Hustvedt’s more than thirty-year marriage to the novelist Paul Auster has only enhanced her public profile as a major American woman of letters, while also giving her huge dollops of Park Slope–boho street cred.

But the awkward news is that in spite of its author’s very palpable skills, ambition, and intelligence, not to mention the critical raves she inspires, The Blazing World comes across more as straitened feminist concept-piece than satisfactory storytelling. It’s didactic and unreal and overthought—more curlicued pseudotreatise than a book to be read with absorption and self-forgetting. The book, indeed, never forgets itself—never abandons its self-reflexive “literariness”—and that’s one of its primary defects.

To crystallize the issue, consider another amuse-bouche from Randall Jarrell. “The novel,” he proposes in “An Unread Book,” “is a prose narrative of some length that has something wrong with it.” Arresting enough as uttered—but also an insight one might take further. It’s not just that every work of fiction, even the best, has something “wrong” with it, but that whatever makes the fiction wrong—whatever defect in conception, form, character, plot, or technique seems to disfigure it—is also the very thing that makes the work what it is, gives it its distinctive shape and feel. Without the “wrong” yet fruitful “idea”—the initial concept Henry James called the donnée—the book cannot come into existence.

Yet paradoxically, the gift is also the spoiler—the element that keeps a writer, ultimately, from achieving self-transcendence. Without Woolf’s inspired decision in Mrs. Dalloway to tell a complicated “double” story about two very different characters fated never to meet—one a psychotic World War I shell-shock victim, the other an introspective middle-aged society lady preparing for a lavish party—the novel as we know it never happens. But the splitting off necessarily produces, too, a painful psychic bifurcation—an emotional dissociation at the heart of the fiction that is never resolved. The book is still a masterpiece—beautifully and urgently so—but like all mortal creations (including some of the world’s loveliest) a bit of a fiasco.

Advertisement

From its title on, The Blazing World could be said to derive, similarly, from a splendid, even incandescent, bad idea. What would happen were one to take the prolific, wildly eccentric, proto-feminist seventeenth-century English woman writer Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle (1623–1673), as inspiration for a modern-day fictional heroine: an equally flamboyant, sixty-something American woman sculptor who, after decades of feeling marginalized on account of her sex, undertakes a kind of crackpot revenge on the misogynist mandarins of the New York art world? One would unfold the sculptor’s colorful back-story—but also embed within it telling references to the long-dead predecessor: a sister-artist (Woolf herself eulogizes Cavendish in A Room of One’s Own) who likewise felt thwarted by jealous and often malicious male rivals.

Intellectually speaking, the parallel might seem promising. Though gamely financed by a kindly yet elderly husband, the more-than-half-loony Cavendish—known as “Mad Madge” to nonplussed contemporaries—found few sympathetic readers for her ever-multiplying oeuvre: a vast, cockeyed assemblage of poems, plays, moral essays, French-style prose romances, scientific treatises, and autobiographical complaints about the unjust treatment accorded shining female “Genius” like her own.

Hardly coincidentally, Cavendish’s best-known work—a bizarre utopian romance from 1666 about a woman who discovers an unknown civilization beyond the North Pole, becomes its empress, and rules over it with the help of a learned and chatty spirit-companion (“the Duchess of Newcastle”)—is entitled The Blazing World. Unlike Hustvedt’s Blazing World, however, the Cavendish book is undiluted wish fulfillment: a lonely, solipsistic, unusually literate woman’s slightly bonkers fantasy of magically acceding to majesty and mastery. As the Duchess writes in the preface (and the peevish tone is characteristic):

Though I cannot be Henry the Fifth, or Charles the Second, yet I endeavour to be Margaret the First…. Rather than not to be mistress of [a world], since Fortune and the Fates would give me none, I have made a world of my own: for which no body, I hope, will blame me, since it is in every one’s power to do the like.

Hustvedt’s story of the angry, intense, oddly “hermaphroditic” sculptor Harriet Burden—she’s six-foot-two, frizzy-haired, big-bosomed, big-hipped, pushy, excitable, strong as any man, and inclined to bellow—is clearly meant as a sort of bittersweet update on Cavendish: a new Blazing World for a crass and still persistently sexist postmodern era. It’s set in the ever-outrageous New York art world: a ghoulish Vanity Fair of billionaire collectors, preening, Proenza Schouler–clad gallerists, greed and careerism disguised as hipster chic, intellectual jargon and pseudotheoretical pretension, and—irradiating everything like nuclear fallout—those staggering, shameful, ever-escalating sums of money now being dropped on so-called “art” old and new.

The tale is told in a tricksy, would-be Nabokovian fashion. Harriet (or Harry, as she prefers to be known) is already dead at the novel’s start, having succumbed to cancer in 2004; the text we read is made up of assorted documents supposedly pertaining to her life and frustrated career. The dossier begins with a mysterious “Editor’s Introduction” by one I.V. Hess—sex unknown—a pedantic mock-biographer figure à la Kinbote in Pale Fire. (I.V.’s sobriquet—like other too obviously “curated” character names here—somewhat portentously brings to mind that of the pioneering, now much-revered woman artist Eva Hesse, dead of a brain tumor at thirty-four in 1970.)

I.V. Hess has presumably assembled everything that follows: pages of lengthy, impassioned, often rageful excerpts from Harry’s voluminous notebooks; yellowing magazine reviews of her few, long-ago shows; and a motley set of “statements” written about her by surviving friends and enemies. The commentators include her voluble, Brooklyn-born writer-boyfriend Bruno; her filmmaker daughter and quasi-autistic son; a psychiatrist friend named Rachel; and assorted art world personalities: Harriet’s one-time collaborator Phineas, a gay black performance artist; the art critic Rosemary Lerner (a fictional knockoff, seemingly, of The New York Times’s Roberta Smith); Oswald Case, bitchy art-world gossip columnist nicknamed “the Crawler”; and various other more or less cartoonish hangers-on. Last of the book’s posthumous reporters is the dying Harriet’s improbable nurse-caretaker, a lovably moronic twenty-something New Age “healer” and Kali-worshiper with the absurd name of Sweet Autumn Pinkney.

As in an epistolary novel, the plot—which turns on a grandiose, decade-long prank Harry has played (unsuccessfully) on the Manhattan art establishment—is gradually revealed through the sequence of documents. A fierce female chauvinist—indeed, she often seems semi-unhinged by the misogyny she feels has kept from her the critical acclaim she deserves—Harriet craves a sort of Blazing World triumph over all who have blocked or disdained her.

Advertisement

First on the offender list, paradoxically, is her own deceased husband, Felix Lord, a legendary, vaguely Leo Castelli–like New York dealer—half-Thai, half-English, beautiful and assured—whose wealth and influence seem to have been accompanied by a total and estranging indifference to his wife’s work. Despite the fact that Felix’s immense fortune has made it possible for his widow to live a pleasingly eccentric bohemian life in newly fashionable Red Hook (where she makes sculptures and takes in various social-misfit lodgers, including elderly lover Bruno), Harriet still harbors a towering resentment toward her late husband, especially after she learns that he was secretly bisexual and routinely unfaithful to her on art-buying trips in Europe.

Yet Harriet’s animus is broad enough to encompass most of the men she knows (“twits, dunderheads, and fools”) and male artists in particular. It’s fueled in large part by her conviction that men who make art automatically benefit from an unconscious sexism shared by men and women alike. A somewhat masochistic fan of popular neuroscience, Harry broods obsessively over those dreary clinical experiments in which groups of college students, given the same essay to read, become far more critical and disparaging when they think it’s written by a woman than when they think it’s by a man. (The tiresome I.V. Hess—or is it Hustvedt?—footnotes, at length, the relevant scholarly bibliography.)

Such unconscious cognitive bias is then amplified—or so Harry is constantly raging in her journals—by intractable cultural hostility toward female intellectual and artistic excellence. Thanks to male insecurity and paranoia, she fumes, talented women artists from Artemisia Gentileschi to Camille Claudel and Dora Maar have been “suppressed, dismissed, or forgotten”—castrated, in effect—by their opposite-sex rivals.

Intellectually fitting, then—if hardly plausible—Harriet’s feminist revenge plot. By way of her huge wads of cash, we learn, she has managed over a decade to bribe three male artists into mounting one-man gallery shows in which the sculpture presented as “theirs” is in fact Harry’s own. (Each he-stooge is allowed to collaborate in some degree in the making of “his” art, but Harry declares herself to be, Cavendish-style, creator-in-chief: hidden “virago mastermind” behind all the work displayed.) Loaded up with samples of her own genius—or so Harriet somewhat rashly presumes—each show will be a critical triumph of the sort debarred her were she to exhibit the same work under her own name. Once these stealth exhibitions have been staged and fêted—several years will separate them—she plans to reveal herself as the Grotesquely Slighted Woman Genius behind everything. Through this somewhat mock-heroic coup de théâtre, she’s convinced, she will expose art-world misogyny in all its phallocentric vileness.

Throughout The Blazing World, Hustvedt invites readers, roman à clef–style, to guess at real-world counterparts for her blowsy, resentment-driven, and (dare one say) thoroughly unlikable “giantess.” Yes, there’s a fleeting Artforum-crossed-with-Trivial-Pursuit fun to be had in it: Harriet’s sculptural installations, described in considerable detail, often suggest well-known works by well-known women artists of the past fifty years. Contemporary art fans will be reminded in particular of the feminist sculptor Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010), whose huge, psychically fraught, and often kitsch stuffed fabric sculptures of breasts, phalloi, and other body parts—not to mention giant spiders, excremental blobs, and the like—only gained wide recognition when the artist, a near centenarian, was in her seventies. (She’s mentioned in The Blazing World as the “divine Louise Bourgeois.”)

Harriet’s first “stealth” show, for example—supposedly the creation of a doltish young silkscreen artist named Anton Tish—is organized around a massive, Bourgeois-like female effigy, shown naked and reclining in “an overblown, three-dimensional allusion to Giorgione’s painting of Venus, finished by Titian.” This cheerless behemoth has hundreds of minute reproductions, photographs, and texts collaged all over its surface and is surrounded by wooden crates containing spooky little dollhouse vignettes. As in many of Bourgeois’s pieces, these dysphoric stage-sets-in-boxes seem to dramatize cryptic memories of sexual abuse and other forms of childhood trauma.

Granted, given Hustvedt’s allusions to an Amazonian phalanx of other women artists—Kiki Smith, Alice Neel, Niki de Saint Phalle, Judy Chicago, Annette Messager, Nancy Spero, Lynda Benglis, Ana Mendieta, Cindy Sherman, Isa Genzken, Yayoi Kusama, Tracey Emin, and Sarah Lucas were only some of the marquee names popping into this reader’s brain—Harriet is perhaps best considered a loose composite. (Virtually every detail in The Blazing World is overdetermined in the same crowded and cross-referencing fashion.) Many of the older artists mentioned above, for example, lived through the feminist movement of the 1970s and 1980s and themselves made pioneering, politically inspired, female-centered “body art”—notably Judy Chicago, whose massive shrine-like installation The Dinner Party (1974–1979), much derided at the time, remains the most memorable artifact of the era’s feminist art wave.

Yet whatever their feminist pedigree, it’s unclear how seriously Hustvedt means us to take Harriet’s often ropey-sounding creations. Are they supposed to be beautiful? uncanny? intellectually challenging? politically incendiary? or maybe just inane and self-absorbed? Tellingly, the revenge plot, which depends on Harriet’s pseudonymous work being celebrated by all, is a bust. The first show draws enough viewers to make Anton Tish a sort of nine-day wunderkind, but the brief public notice is eclipsed almost at once by the fact that he subsequently disappears from both the art world and the novel.

The second show, The Suffocation Rooms—concocted with Phineas the performance artist—fares even less well. Not because it lacks claustrophobic drama: as recollected by Phineas, it consists of a walk-through series of interconnected and stiflingly hot rooms, each containing the same eerie tableau: two cadaverish and life-sized “metamorphs” sitting at a table. These humanoid mannequins grow larger, Alice in Wonderland–style, as the viewer moves from room to room. Again, the visual idiom conjures up Bourgeois, especially in the seventh room, in which an androgynous wax homunculus with frizzy red hair (like Harry’s own), “small breast buds,” and a “not-yet-grown penis” clambers out of a box. Harriet calls this disconcerting little figure “the hungry child”—a Hustvedtian reference, perhaps, to one of Bourgeois’s creepier wax-figure installations from 2003, The Reticent Child.

But one wonders—and not for the first time—about Hustvedt’s intentions. The kind of lumpy wax or latex-like, purportedly “feminocentric” art that Harry favors does not appeal to everyone, obviously: like feminism itself, it can be relentlessly joyless and didactic. (Not too many sight gags in Kiki Smith.) The fact that one can’t get a bead on Hustvedt’s own view of her heroine’s creations—whether she regards them as magnificent or hideous or something else entirely—suggests something of the novel’s underlying emotional confusion, especially as it winds down.

Entropic, indeed, the novel’s final section, in which Harriet stages the last of her hoaxes with the assistance of a bona fide Matthew Barneyesque art star: a handsome, mysterious, fairly sinister conceptualist known as Rune. Touted for his morbid video diaries, Orlan-like “plastic surgery” films, and chilling interest in human–robot hybrids, Rune doesn’t need Harry’s money; he merely wants to confirm his bad-boy reputation by getting in on what he sees as an ironic, Joseph Beuysian art joke. Harriet, pathetically, is mesmerized by him.

The show she and Rune concoct—a huge and disorienting labyrinthine installation entitled Beneath—is immediately hailed (devastatingly for Harriet) as the “genius” Rune’s crowning masterpiece. The show is mobbed; and in the subsequent hubbub, no one believes her anguished protests—either that the labyrinth piece is actually hers or that she made the earlier work attributed to Tish and Phineas. Rune, arch-calumniator, denies having ever collaborated with her and publicly derides her as a jealous, self-obsessed crone. Her hopes blasted, she succumbs soon enough to the cancer that will kill her.

The Blazing World ends in anticlimax; no doubt in part because Rune—while meant as dark shaman-like conniver—is so feebly and bewilderingly drawn. Yet one also feels that Hustvedt has let the novel slip away from her. Harriet’s grand stratagem has been scotched, but so what? Was it ever a plausible-enough scheme to sustain a narrative? What are we to conclude about women artists and the art establishment? (At least one character in The Blazing World thinks Harry’s revenge plot an exercise in passive-aggressive self-nullification.) Given the nutty complexity of her plan, a reader might be forgiven for thinking Harriet disastrously dim as well as a monomaniac. The novel’s last section—devoted to Sweet Autumn Pinkney’s account of nursing Harriet in her fatal illness—is genuinely touching, but the pathos seems due more to Sweet Autumn’s New Age philosophizing and kindly comical chatter about auras than anything preserved in Harry’s anguished, supposedly Lear-like final journals.

The difficulty has to do, ultimately, with the overwhelmingly allusive and mediated nature of Hustvedt’s fictional world. It’s not just the bookwormish invocation of Margaret Cavendish (more on that in a moment); virtually every aspect of the novel is similarly overschematized: citation-driven, cerebral, and unconvincing. The story itself, as noted, is in mediated form—via “I.V. Hess” and the chorus of other characters. Yet to borrow one of Harriet’s own gnomic phrases, the “Hermaphroditic polyphony” supposedly created by these multiple narrative voices never gathers force and lifts off. Unlike Nabokov, Hustvedt often has trouble giving individual identities to fictional speakers: Harry’s sober-minded daughter Maisie and psychiatrist friend Rachel, for example, sound so much alike that it’s hard for a reader to remember at times who’s speaking.

Relentless intertextuality makes reading The Blazing World a bit like reliving one’s long-ago Ph.D. orals exam in English literature. It’s hard not to feel nervy and clammy-palmed when challenged to integrate into one’s understanding of the narrative Hustvedt’s madly refracting references to Paradise Lost, Aeschylus, Dante, Sir Thomas Browne, Hildegard of Bingen, Thomas Traherne, Christopher Smart, Emily Dickinson, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Whitman, Melville, J.G. Ballard, Joan Didion, Philip K. Dick, and countless others.

Nor are heavy-hitting philosophical allusions debarred: bone up here on Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Hegel’s Phenomenology of the Spirit, Vico, Schrödinger (and his cat), Freud and Breuer and Anna O., Erwin Panofsky, Edmund Husserl, Hannah Arendt, Steven Pinker—not to mention the collected works of gender theorist Judith Butler. Watch your head, though: Hustvedt flings around the name of Guy Debord, founder of the revolutionary Situationist movement of the 1950s and 1960s, as if he were a grubby Mike Kelley stuffed toy. The book seems to scatter itself intellectually in all directions.

Which returns us to hapless learned lady Margaret Cavendish, putative model for “blazing” Harriet. It is true that Harriet invokes the Duchess often—usually mawkishly—as her symbolic progenitrix. (“I am back to my blazing mother Margaret. Margaret, the anti-Milton. She gives birth to worlds,” etc.) At her death Harry leaves behind a huge unfinished sculpture of a woman Bruno calls “her Margaret, her Blazing World Mother creature.”

Yet confusingly, Hustvedt’s heroine appears to have other prototypes, too. Virginia Woolf (to whom Hustvedt is often lazily compared) is everywhere in The Blazing World—A Room of One’s Own being just one of Woolf’s works to be conspicuously featured. The novel’s most striking yet awkward intertextual link, however, is to Woolf’s feminist mock-biography Orlando (1928)—a surreal modernist fable in which the eponymous hero-heroine, born a man in the Elizabethan Age, undergoes a mysterious sex change in the early eighteenth century and lives on as a woman into the 1920s. Like The Blazing World, Orlando is an allegory of sorts, and Woolf’s intellectual preoccupations—what constitutes sexual difference? how much do social norms shape one’s sense of male and female? if one adopts the clothes of the opposite sex will one’s sexual identity or even sexual orientation also be altered?—are Hustvedt’s too.

Orlando’s influence on The Blazing World is reflected most obviously in the distracting (and annoying) male and/or female monicker of Hustvedt’s heroine: Harry/Harriet. There’s a specific reference here for the eagle-eyed: midway through Orlando, as a counterpoint to her hero’s male-to-female transformation, Woolf introduces a secondary character who appears to change from female to male: the “Archduchess Harriet of Roumania.” Six-foot-two, lurching, loud, and obnoxious, with a face like a “monstrous hare,” the scarecrow Archduchess becomes infatuated with the young, still-male Orlando in the seventeenth century but is comically rebuffed when she expresses a wish to marry him. Once Orlando becomes a woman, however—a half-century later—the duchess reappears and reveals herself/himself to have been a man all along, namely, the “Archduke Harry of Roumania.” Apparently ambisexual, the versatile “Harry” proposes himself as a husband for Orlando, although the latter—now incontrovertibly female—rejects him yet again.

Woolf’s Harry/Harriet jape itself has multiple sources—one of which may be the character of the androgynous “Harriet Freke” in Maria Edgeworth’s 1800 comic novel, Belinda: a wild, mannish, horse-faced, pistol-wielding admirer of Mary Wollstonecraft’s pioneering feminist treatise, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. (Unsurprisingly, this same “Mrs. Freke” is a woman of “unnatural” sexual tastes: she lusts fruitlessly after the book’s goody-goody heroine.) But Woolf is also having fun at the expense of her friend and former lover, the sapphic seductress (and pattern for Orlando) to whom the book is dedicated, Vita Sackville-West—Vita’s husband being yet another Harry: the homosexual diplomat and writer Harold Nicolson.

Like competing radio signals coming in on the same frequency, Hustvedt’s Cavendish and Woolf references would seem to be at war with one another. Together they produce a kind of conceptual static—a thematic disturbance serious enough to destabilize, in particular, The Blazing World’s exceedingly flimsy heterosexual logic. Lesbianism, it should be pointed out, is never an explicit topic in Hustvedt’s fiction, even though the heroine looks and sounds, frankly, like a big old dyke. (By contrast, the novel teems with gay men.) Despite the fact that she’s freakishly butch and bluff, goes by a man’s name, and is wont to daydream for hours about notorious male impersonators like the science fiction writer “James Tiptree Jr.” (revealed after she murdered her husband and committed suicide in 1987 to be the sapphistical Alice Bradley Sheldon), Harriet, we’re asked to believe, is not only straight herself, but bizarrely enticing to men (or at least to gay husband Felix, boyfriend Bruno, kinky Rune). The whole erotic set-up feels incoherent. A lesbian-friendly reader, in particular, keeps waiting for the other Doc Marten to drop.

The cognitive dissonance both undermines one’s confidence in Hustvedt’s powers of observation and curtails the intellectual force of her feminist critique. One used to hear it proclaimed—back in the bad old radical lesbian-separatist days of the 1970s—that “feminism is the theory and lesbianism the practice.” Hustvedt obviously never got the memo (though admittedly it was a ball-buster). Indeed, consciously or not, she’s mum on any potentially sapphic historical background for her heroine’s increasingly militant man-baiting.

Which would all be okay, of course—authors can do whatever they want with their characters—except that the hetero-Harry premise, besides straining credulity, seems painfully implicated in Hustvedt’s monotonous, one-dimensional, and ultimately inaccurate picture of art history. Yes, the women-haters are always with us, but has their influence ever been as cruelly disabling to the female sex as Hustvedt implies? Without even going back to such colorful and buoyant nineteenth-century figures as the American sculptor Harriet Hosmer (another Harriet) or the French painter-sculptor Louise Abbéma (lover of Sarah Bernhardt), it doesn’t take much to drum up a small marching band of lesbian and bisexual women painters, sculptors, designers, photographers, and filmmakers, all of whom somehow managed to flourish at a very high level despite patriarchal obstacles. Surely Rosa Bonheur, Alice Austen, Marie Laurencin, Eileen Gray, Romaine Brooks, Gwen John, Germaine Dulac, Florence Henri, Sonia Delaunay, Tamara de Lempicka, Germaine Krull, Gluck (Hannah Gluckstein), Frida Kahlo, Berenice Abbott, Gisèle Freund, Claude Cahun, Hannah Höch, Enid Marx, Lenore Tawney, Agnes Martin, and many more would make the grade, not to mention such grandly influential art-historical figures as Gertrude Stein—master promoter of modernist art, collector extraordinaire, and avant-garde figure in her own right—or the fascinating Betty Parsons, the first New York gallerist to stake her reputation on Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Agnes Martin, and other major Abstract Expressionists.

Add living artists into the mix—Joan Snyder, Maggi Hambling, Annie Leibovitz, Catherine Opie, Mickalene Thomas, Zoe Leonard, Nicola Tyson, Harmony Hammond, Amy Sillman, Louise Fishman, Roni Horn, Nicole Eisenman, Barbara Hammer, Deborah Kass, Patricia Cronin, Alison Bechdel, A.L. Steiner, Sadie Bening, Carrie Moyer, R.H. Quaytman, Keltie Ferris, and so on—and one comes away feeling that Hustvedt has suppressed a rather large wodge of twentieth- and twenty-first-century art history so as to enable her heroine to wallow morosely in that lugubrious untruth repeated like a doom in The Blazing World:

All intellectual and artistic endeavors, even jokes, ironies, and parodies, fare better in the mind of the crowd when the crowd knows that somewhere behind the great work…it can locate a cock and a pair of balls.

Cock and balls and bollocks. When it comes to Harry/Harriet, Hustvedt seems to want it both ways. “Harry,” as pretend-roaring girl, may share something of the stone-butch appearance and swashbuckling she-male energies one associates with certain lesbian artists—witness Brooks, Cahun, Martin, or, today, Nicole Eisenman—but since she is supposed to be a victim, one of Patriarchy’s Casualties, she can’t be a real lesbian (or even think about being one or acknowledge clearly that such women exist). A sapphic Harriet/Harry would inevitably remind readers of precisely that robust lineage of lesbian and bisexual artistic rebels who don’t seem to exist in the vacuum-packed, curiously dyke-free milieu Hustvedt imagines the modern art world to be. The result is a feminist fantasy at once insulated, self-contradicting, and strangely stagnant.