The last person to be hanged as a witch in Boston, Massachusetts, was an Irish laundrywoman named Ann (or perhaps Mary) Glover, put to death on November 16, 1688. A virtual slave who barely spoke any English, a stubborn Catholic in a city of stubborn Puritans, Goody Glover stood accused of casting spells on four of her employer’s six children after one of them, thirteen-year-old Martha Goodwin, claimed to have caught Glover’s daughter stealing laundry. The elderly defendant could speak only Gaelic on the stand; she could recite the Lord’s Prayer only in that language or in Latin, and never perfectly: proof positive, to her accusers, that there must be something amiss with her soul. A local merchant, Robert Calef, would later protest: “Setting aside her crazy answers to some ensnaring questions, the proof against her was wholly deficient. The jury brought her in guilty.”

Shortly after her hanging, an ambitious young Boston divine (who was also the Goodwins’ minister), twenty-six-year-old Cotton Mather, published an account of the case, Memorable Providences, Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions (1689), which also included “an Appendix, in vindication of a Chapter in a late Book of Remarkable Providence, from the Columnies of a Quaker at Pen-silvania.” Mather himself had examined “the Hag” and kept one of the afflicted Goodwin children for a time in his own home. Goody Glover’s death, as she herself had predicted on the scaffold, failed to stop their fits. Mather took pains to demonstrate the scientific and legal rigor of the case:

To make all clear, The Court appointed five or six Physicians one evening to examine her very strictly, whether she were not craz’d in her Intellectuals, and had not procured to her self by Folly and Madness the Reputation of a Witch. Diverse hours did they spend with her; and in all that while no Discourse came from her, but what was pertinent and agreeable…. In the up-shot, the Doctors returned her Compos Mentis; and Sentence of Death was pass’d upon her.

Thus persuaded that Goody Glover had been treated with impeccable rationality, Mather sped his volume on its way with an exhortation:

Go then, my little Book…. Go tell Mankind, that there are Devils and Witches; and that tho those night-birds least appear where the Day-light of the Gospel comes, yet New-Engl[and] has had Exemples of their Existence and Operation; and that no[t] only the Wigwams of Indians, where the pagan Powaws often raise their masters, in the shapes of Bears and Snakes and Fires, but the House of Christians, where our God has had his constant Worship, have undergone the Annoyance of Evil spirits.

Soon after its publication, Cotton Mather’s Memorable Providences entered the library of the Reverend Samuel Parris, first minister of Salem Village, a Puritan settlement fifteen miles north of Boston, perhaps as early as 1689, when Parris was called to the contentious, troublesome parish, the fourth minister to be summoned in sixteen years. When the minister’s nine-year-old daughter Betty and his eleven-year-old niece Abigail Williams began behaving strangely in February 1692, Parris had good reason to believe that they, like the Goodwin children of Boston, had been bewitched, a conviction he confirmed by beating his South American slave, Tituba, until she confessed.

Tituba’s confession, however, hardly ended the affair; instead, it brought on a cataclysm. The girls continued to have seizures; Tituba, and then her husband, John Indian, named a few village women as witches; more adolescent girls began throwing the same inexplicable fits as the girls in the minister’s house; and soon neighbors were accusing neighbors of lurid acts of malevolence: invisible “penching, biting, and Choaking,” stopping the wheels of a cart by glancing at it out the window, withering newborn babies and bothersome spouses by sticking dolls, “poppets,” with pins or simply by thinking negative thoughts. By July 1693, Salem Village and its neighboring settlements counted, in Robert Calef’s tally:

Nineteen persons having been hang’d, and one prest to death, and Eight more condemned, in all Twenty and Eight,…and not one clear’d; about Fifty having confest themselves to be Witches, of which not one Executed; above an Hundred and Fifty in Prison, and above Two Hundred more accused.

On this occasion Cotton Mather ventured doubts that justice had been served; unlike Goody Glover, a poor foreign papist, the condemned of Salem included leading members of the town’s tight-knit society. Rebecca Nurse, hanged on July 19, 1692, may have been an elderly woman like so many convicted witches, but unlike them she was also upright, well-off, and influential, the mother of eleven and grandmother of twenty-six. John Proctor, a strapping farmer of sixty, had exerted exceptional authority over the community through his wealth, his fearsome physical strength, and his rectitude. Now he and his wife Elizabeth stood accused by their maid and their former maid of strange supernatural crimes. Pregnant with their fourth child, Elizabeth was remanded to jail, but John Proctor swung from the gibbet of Gallows Hill on August 19, 1692.

Advertisement

Another venerable yeoman farmer, Giles Corey, was put to torture in a grotesque and unsuccessful effort to extract a confession: stripped naked, he lay in an open grave beneath a wooden board on which the magistrates loaded giant boulders. It took three days to crush the life out of the fierce old man, whose only words throughout the ordeal were “more weight.”

With the execution of such prominent citizens, the Salem trials rapidly lost their momentum; in August and September 1692, the frenzy of accusations and executions shifted to nearby Andover, and then stopped just as abruptly after another few months of juridical chaos. The supposed cause of it all, the Indian slave Tituba, languished in jail for thirteen months until an unknown Salemite paid her bail of seven pounds and effectively bought her from the Parris family.

The Salem witch trials remain an enigma, an eruption of religious fanaticism and mass hysteria, but also, as the trial records clearly demonstrate, a violent, strange expression of the normal tensions inherent in village life. Accusations in a spare, essential English lay bare the conflicts between yeoman farmers like John Proctor and seafaring tradesmen like Reverend Parris, who had owned a sugar plantation in Barbados before taking up the ministry in the chill climes of Massachusetts Bay.

Sarah Holton, recently widowed, accused her next-door neighbor Rebecca Nurse not only of supernatural crimes, but also, with perfect plausibility, of “calling to hir son Benj. Nurs to goe and git a gun and kill our piggs,” after said “piggs” had trampled the Nurse family’s vegetable patch, the family’s livelihood wrested by years of labor from New England’s stony soil. No wonder upstanding Rebecca seems to have had a temper as well as an iron backbone. Old Giles Corey endured his deadly pressing to preserve the family real estate: by dying under interrogation rather than confessing to witchcraft, he ensured that his property would pass to his sons rather than being confiscated by the state.

There were also extraordinary circumstances to reckon with: for two years, starting in 1690, indigenous Wabanaki raiders had attacked Anglo-American colonists in Maine and northern Massachusetts, including people involved in the Salem trials.1

In 1952, this troubling New England episode began to exert an increasing attraction on the thirty-eight-year-old playwright Arthur Miller, whose Death of a Salesman had triumphed on the stage in 1949, winning a Pulitzer Prize and a Tony Award. In 1951, Miller flew to Hollywood with the director Elia Kazan to promote a script about corruption among longshoremen on the New York waterfront. There he formed a friendship, to his unending surprise, with a lonely, troubled Angelena to whom the studios had given the name Marilyn Monroe.

But the prospective script turned out to pose problems for the film industry: as the United States began to feel its muscle as a world power in the aftermath of World War II, Miller and Kazan’s story of crooked union capitalists and oppressed dock workers seemed to contradict the proverbial American Dream at the very moment when that dream seemed most invincible. Film, with its mass appeal, posed a dilemma that the stage did not; after consulting with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Harry Cohn, the head of Columbia Pictures, agreed to produce the script on one condition: Miller would have to change the villains from corrupt businessmen to corrupt Communist union leaders.

The FBI was not the only government body on the hunt for Communists in 1951. The US House of Representatives had already set up its Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), charged with rooting out Communist activity in every sphere of civilian life; in the Senate, Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin had begun to denounce the legions of secret Communists embedded in left-wing strongholds like the labor unions and the arts. With Death of a Salesman, Miller had already emerged on the side of the working class; Linda Loman’s heartbreaking eulogy of her husband Willy also described the task that Willy’s creator had set for himself: “Attention must be finally paid to such a person.” Miller refused to change his script to satisfy either Cohn or the FBI. Instead, he flew back to New York, with both Salem and Marilyn Monroe firmly implanted in his imagination.

Miller’s autobiography, Timebends, tells what happened next.2 Kazan saw him just as he was on his way to do research for The Crucible in Salem and told him disturbing news: to preserve his cinematic career, the director had decided to supply HUAC with the names of former members of the Communist Party. Miller stopped at the Kazans’ house in Connecticut before driving north to Massachusetts, and as the conversation progressed, he realized where the limits of friendship lay:

Advertisement

Had I been of his generation, he would have had to sacrifice me as well…. I could still be up for sacrifice if Kazan knew I had attended meetings of Party writers years ago and had made a speech at one of them.

Writing decades later, Miller could look back sadly:

It was not [Kazan’s] duty to be stronger than he was, the government had no right to require anyone to be stronger than it had been given him to be, the government was not in that line of work in America. I was experiencing a bitterness with the country that I had never even imagined before, a hatred of its stupidity and its throwing away of its freedom. Who or what was now safer because this man in his human weakness had been forced to humiliate himself?3

Miller continued onward to Salem to work through the trial records:

In a sense, I went naked to Salem, still unable to accept the most common experience of humanity, the shifts of interests that turned loving husbands and wives into stony enemies, loving parents into indifferent supervisors or even exploiters of their children, and so forth. As I already knew from my reading, this was the real story of ancient Salem Village, what they called then the breaking of charity with one another.

By 1953, Arthur Miller had spun these troubles out into the four eloquent, devastating acts of The Crucible. The play’s first performances were only moderately successful, but in subsequent productions its dramatic treatment of the Salem witch trials proved to have a resonance extending far beyond its particulars of time and place. Forty-nine years after Sir Laurence Olivier produced The Crucible at the Old Vic theater in London in 1965, the work has returned under the pitch-perfect guidance of the South African director Yaël Farber. On this occasion, however, the venerable old theater has been gutted and reshaped to present this season’s offerings in the round, a transformation that adds further intensity to Miller’s relentless drama.

Although it has often been described as an allegory of McCarthyism, The Crucible is not an allegory, a genre Miller detested. Miller himself describes The Crucible as a tragedy, and it is a tragedy, an exceedingly complex tragedy in which no fewer than three of the main characters experience what Aristotle identifies as the very essence of tragic pathos: a fateful turnaround (peripeteia) and a process of revelation (anagnôrêsis) that leads to profound recognition of who and what they—we—are. Miller, like Sophocles, also creates turns of character within these turns of fate, conveyed with a Sophoclean precision of words and, in each case, a Sophoclean outcry against the gods.

The play is not historically accurate in all its details, but Miller read the trial records with extraordinary insight and distills the essences of Salem’s particular madness in his composite characters and in his inexorable plot. The magic circle that stood at the center of Greek theater imposed rules of a different kind than the rules of history, and it is these same dramatic rules of integrity, lyricism, and ritual that Miller obeys to convey his tragic truth. In many respects, The Crucible is a Greek tragedy, addressed, overtly or incidentally, to the Greek-born friend Elia Kazan, who had, he thought, committed a tragic act of almost primal significance by naming names to the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Names stand as close to the heart of The Crucible as witchcraft itself, and for Miller there definitely are witches, just as the devil’s work is definitely afoot in Massachusetts.

From his study of the Salem papers, Miller identified two basic motives behind the accusations of witchcraft: sex and real estate. Neighbors accused neighbors of crawling into each other’s beds in spectral form to choke and pinch, airing private fantasies in public; young girls writhed and screamed on the stand, telling salacious tales about village men.

But there were also practical benefits to be gained by inducing justice to take its course. A convicted witch forfeited property, which was confiscated and put up for sale. For the frequent accuser Thomas Putnam, who had the liquid cash to buy up these confiscated properties, there was almost always a plot of land at stake when he began to “cry out” his fellow citizens.4 His wife, Goody Ann, faced a far greater mystery: Why did so many of her children die? Thus the base human instincts of greed, resentment, and sexual passion drove Salem to its madness, but the responses of church and state were madder still: ministers and magistrates were so intent on preserving the forms of piety, learning, and legality that they never paused to question whether what they were doing made any sense until the investigations began to take aim at people of high status, people like themselves. Then the witch hunts stopped in their tracks.

Miller changes the ages of two central figures in the Salem Village trials: Abigail Williams, one of the girl accusers, and John Proctor, the respectable farmer who protested against the proceedings from the beginning and died on the scaffold as a convicted witch. By raising the age of Abigail Williams from twelve to seventeen, Miller creates a plausible sexual link between the onetime servant girl and her former master, John Proctor. He adds a telling biographical detail: she has seen her entire family murdered in an Indian raid. He drops Proctor’s age from sixty to thirty or forty, turning the village elder into a virtual alter ego.

The story that Miller creates is an interweaving of greed and passion: Abigail Williams, in the company of some other girls, has been telling fortunes in the woods with Tituba, hoping to win back John Proctor, with whom she had an affair, by cursing his wife, but the girls are discovered by Abigail’s uncle, Reverend Parris. Abigail’s only escape is to accuse Tituba of witchcraft and terrorize the other girls into acting as if they are possessed, and the play opens with little Betty Parris lying comatose on her bed as neighbors begin to file in to see what has happened. When Parris and then the Putnams begin to warm up to the idea that witchcraft might be involved, the accusations begin to fly more wildly.

Parris has called in a learned minister from Boston, Samuel Hale, who professes skepticism but falls in, for the moment, with the growing hysteria. His reasoned words seem to contrast with Betty Parris and her seizures, but it is in fact his learned opinions that keep the panic hot. Three of the community’s most sensible citizens pass through the Parris house in this opening act: elderly Rebecca Nurse, who assures everyone that the girls will snap out of their fits soon enough, crusty old Giles Corey, who calls the panic nonsense, and John Proctor, who deplores the turn of events but feels compromised because of his adultery with Abigail and his continuing attraction to her.

Eight days later, Miller takes us inside the house of John and Elizabeth Proctor, whose damaged marriage he portrays with painful precision. The accusations of witchcraft have spread, and as the act progresses the list of accused witches will come to include Rebecca Nurse and Elizabeth Proctor, who is taken off to jail at its close. Abigail has confessed to Proctor that the girls’ fits are a fraud, but he does not see how to denounce her convincingly.

The third act takes place in an antechamber to the courtroom during the trials of Elizabeth Proctor and Rebecca Nurse; Proctor brings in his servant, Mary Warren, to confess that the girls’ fits have been faked all along: “It were pretence.” The deputy governor convenes an ad hoc court on the spot, but Mary Warren collapses, bullied on all sides: by Abigail and the other girls, and by the deputy governor, Thomas Danforth. Proctor’s kindly words are too much for her; viciously pressured, she suddenly turns on her employer with equal viciousness and accuses him of witchcraft and lechery (a capital crime in seventeenth-century Massachusetts). Proctor confesses his adultery with Abigail, and Elizabeth Proctor is brought in to confirm that her husband is “a lecher.” As the proceedings grow more and more grotesque, the Boston minister Samuel Hale realizes how badly they have gone wrong, and storms out.

In the final act, set in the Salem Village jail, Proctor and Rebecca Nurse have been condemned to hang because they refuse to confess their guilt; Elizabeth Proctor is pregnant and cannot legally be executed until the baby is born. A broken and contrite Reverend Hale has been moving among the prisoners, encouraging them to sign confessions, however false, and save their lives; to die needlessly, he declares with his new insight, is to serve pride rather than God’s true purpose. Rebecca Nurse still refuses to confess. Because he feels unworthy to die alongside so blameless a woman as Rebecca (Miller acutely explores the psychological nuances of Puritan angst), Proctor begins to sign a confession of his guilt, encouraged by Elizabeth to do so as she apologizes for her own deficiencies in their marriage.

In the end, however, Proctor balks, and, in an impassioned speech, tries to explain why he will not allow the court to use his name. Suddenly aware of his own integrity, he walks bravely off to the scaffold. Hale pleads with Elizabeth to convince her husband to live, but she replies, “He have his goodness now. God forbid I take it from him!”

Names are as a constant theme in The Crucible, names that Elia Kazan supplied to HUAC, names that Miller knew he would not reveal to any apparatus of state gone amok. Names stand at the center of one of the earliest preserved tragedies, the Agamemnon of Aeschylus, where even the name of Zeus seems labile and uncertain: “Zeus, whoever he might be, if it is dear to him to be called this, that is how I will address him.”

The name that appears above the title of The Crucible at the Old Vic is that of its John Proctor, Richard Armitage. Of all the people involved in this production, Armitage certainly took the greatest risk. A self-described late bloomer,5 absent from the stage for thirteen years, best known as the dwarf prince Thorin Oakenshield in Peter Jackson’s Hobbit trilogy, he wagered his future as an actor on a role that has its own considerable pitfalls. Most of the time, Miller portrays John Proctor as a laconic farmer, but on occasion Proctor suddenly waxes lyrical, as when he tries to woo back his wife in the second act:

On Sunday let you come with me, and we’ll walk the farm together; I never see such a load of flowers on the earth. Lilacs have a purple smell. Lilac is the smell of nightfall, I think. Massachusetts is a beauty in the spring!

The principle on which Proctor finally finds his bedrock, his name, is a personal conviction, not an abstract principle. The very specificity of his defiance is what saves his character from allegory—he is no Pilgrim, or Good Deeds, or even Everyman. His great speech of self-affirmation does not make a great deal of rational sense. Miller’s stage directions call Proctor’s response “insane.” But it is not insane: this anguished but truthful man refuses to collude in a lie. He can only roar: “I am John Proctor!… It is no part of salvation that you should use me!”

But because Proctor’s defiance is felt as much as reasoned, and felt out step by tentative step, this fallible, personal, instinctive attachment to personal integrity is devilishly hard to pin down, let alone to play. The line “God in Heaven, what is John Proctor, what is John Proctor?” rings on one level as pure rhetoric, but this is also the essential point of recognition for every tragedy, and Miller, as a careful craftsman, pauses to state the question openly to ensure that the point is taken. For in this tragedy, “What is John Proctor?” is also, searingly, Arthur Miller asking himself “What is Arthur Miller?” with the hot breath of HUAC on his neck. And in finding John Proctor’s way through the confusion Miller is also finding the strength that will serve, when the time comes (and it did come in 1956), to keep his own name intact. At the price of a term in jail, he refused to name names to the committee and said of his own past, “I have had to go to hell to meet the devil.”

During the first days of the Old Vic production, “What is John Proctor?” posed another question as well, with an answer that was not yet clear: “What is Richard Armitage?” Rarely does an actor play so close to the bone, and for such stakes. His Proctor is gentler than the hard-edged Puritan in Miller’s text, whose whip is always ready to hand, although Armitage has deliberately added a gruff edge to his silken voice, suddenly lifted when he rhapsodizes to Elizabeth about the purple smell of lilacs. His performance, magnificent, discloses the true heroic temper of Miller’s tragedy

Farber’s production, however, is not a star turn; it presents an ensemble as tightly knit as old Salem Village, with moving performances from every corner. Adrian Schiller’s dapper little Reverend Hale moves from cool self-assurance to shattering remorse. Jack Ellis, as Deputy Governor Thomas Danforth, assumes the balletic stance of an eighteenth-century dandy, barking out his orders with diction as sharp-edged as his words: “This is a sharp time.”

Miller’s portrait of the Proctors’ disintegrating marriage is evidently drawn from life; dedicating The Crucible to his wife Mary Slattery was a last-ditch gesture that failed. The Proctors bicker as the Millers must have done. With quicksilver speed, Anna Madeley, as Elizabeth Proctor, shifts her mellifluous voice from honey to gall as suspicion poisons her thoughts; her righteousness in the first three quarters of the story, in her husband’s words, “would freeze beer,” but in the final scene it exudes a supernal glow.

Farber disposes her actors’ bodies with daring abandon: Samantha Colley, as a scheming, bullying Abigail Williams, catches Proctor in a flying leap that brings them both crashing to the floor. Mary Warren (played by Natalie Gavin), the Proctors’ browbeaten maid, turns on her employers with furious spite when she realizes that the lines of authority have suddenly been reversed in this new witches’ regime. The harshness of Puritan life is revealed in grim colors, stark sets (by Soutra Gilmour), and a pervasive grime that turns, in the final act, to a literal shower of ashes. Richard Hammarton’s rumbling score hints eerily at the coming storm.

Farber’s staging begins with a tableau: the actors assemble, some sitting on chairs, and look at the audience, as a barefooted Tituba makes a slow circular dance around the performance space, holding a smoking kettle. Farber believes that theater is still an ancient ritual, and thus, like ancient Greek actors, these players mirror us as they mark out the charmed circle that, in ancient Greece, was believed to host a holy liturgy. There may not be witchcraft afoot in the Old Vic, but there is certainly enduring magic. When staged at this level, The Crucible rings true in every line.

This Issue

September 25, 2014

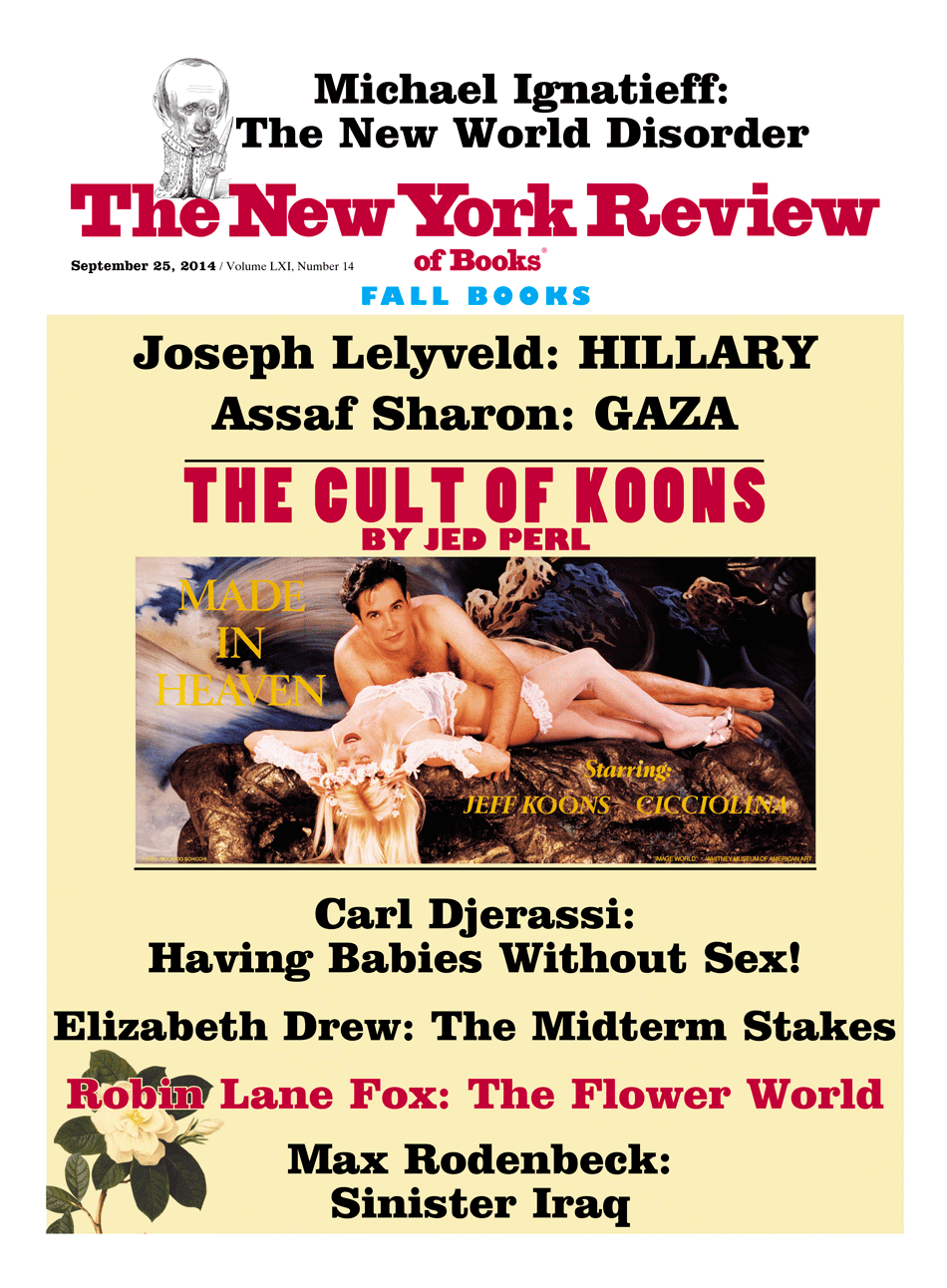

The Cult of Jeff Koons

Obama & the Coming Election

Failure in Gaza

-

1

See Mary Beth Norton, In the Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692 (Knopf, 2002). ↩

-

2

Grove, 1987. ↩

-

3

After Miller’s script was turned down, Budd Schulberg was assigned to write the script of the film that became On the Waterfront under Kazan’s direction. Kazan and Schulberg made it clear that the story’s central issue was the Marlon Brando character’s willingness to testify against the corrupt bosses of the union. With Sam Spiegel as producer, the Communists that Harry Cohn insisted on were left out. ↩

-

4

Or so he thought: he died deeply in debt. ↩

-

5

Richard Armitage, in an interview with Chris Harvey, The Daily Telegraph, June 25, 2014, describes his career as “a slow climb. I started late, and it’s taken 20 years.” ↩