Robert Katzmann, who is now the chief judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, has been a federal judge for over fifteen years. In his prior academic career at Georgetown Law School he studied the legislative process and engaged in projects intended to improve the relationship between Congress and the federal judiciary. He regards those two branches of government as partners, rather than rivals, in performing their constitutional roles.

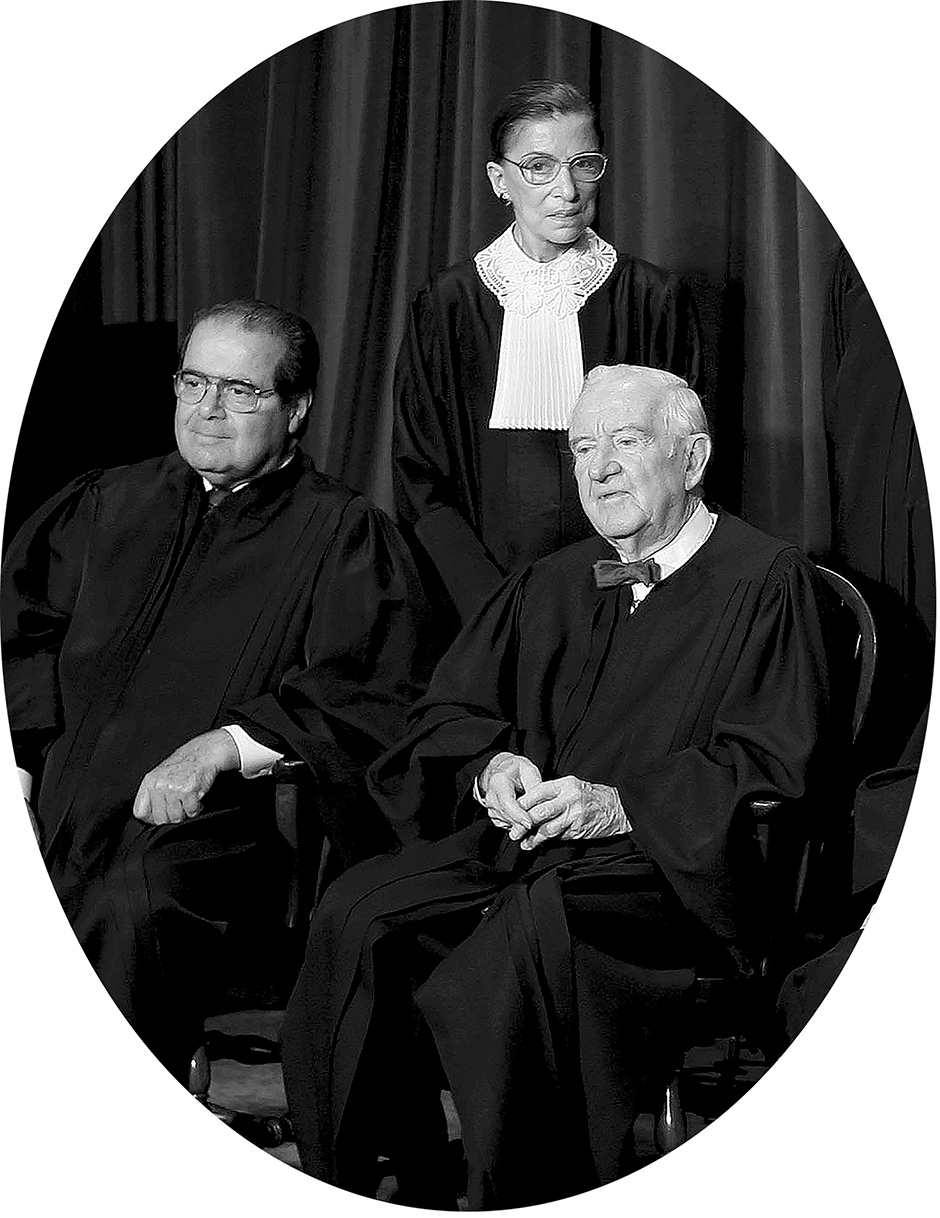

His new book, Judging Statutes, explains why it is appropriate to seek to understand the intent of Congress when confronted with vague or ambiguous statutory provisions. He disagrees with Justice Antonin Scalia and the so-called textualists who would not allow judges to look at any legislative history when confronted with statutory questions. In their view all legislative history is equally irrelevant. Katzmann endorses Chief Justice John Roberts’s statement that

all legislative history is not created equal. There’s a difference between the weight that you give a conference report and the weight you give to a statement of one legislator on the floor.

In the introduction to his book Katzmann notes “the simple reality” that an enormous increase in the number of new statutes has led to a corresponding increase in the number of judicial decisions in which federal courts are called upon to interpret them as they apply in one situation or another. Now a substantial majority of the Supreme Court’s caseload involves statutory construction. And of course the work of lower federal court judges, administrative agencies, and practicing lawyers increasingly involves the interpretation of federal statutes. His topic is unquestionably important, and he has shed new light on the ongoing debate between “purposivists” and “textualists.”

A few statistics illustrate how enormous the increase in congressional activity has been. Volume 1 of the Statutes at Large, which comprise the official text of the laws enacted by Congress, contains a total of 755 pages. Those pages include all of the legislation enacted by the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th Congresses during the first decade after the Constitution’s ratification. The laws enacted by just one Congress (the 82nd) in 1951 and 1952, while I was serving on the staff of a House subcommittee, fill two volumes containing over 2,200 pages. And there are over eight thousand pages in the seven books containing the laws enacted by the 111th Congress in 2009 and 2010.

To produce the laws that were actually enacted, Congress has spent more days in session and the sessions have become longer. Moreover, those laws represent only a small fraction of the number of bills that were introduced and voted upon in both the House and the Senate. And of special relevance, the time a member spends in session may be far less productive than his other work. “In 1885, a young scholar, Woodrow Wilson, wrote: ‘Congress in session is Congress on public exhibition, whilst Congress in its committee rooms is Congress at work.’” According to Katzmann: “Since the early nineteenth century, congressional committees have been central to lawmaking. Without committees, Congress could not function.”

Whether or not it is wise for legislators to rely so heavily on the work of their numerous committees—there are some 130 standing committees in the House and 98 in the Senate—and, more narrowly, on their staffs, in fact they do, and given the scarce time available for reflection and deliberation, they must. They accept the trustworthiness of statements made by their colleagues on other committees. (I remember a private conversation with Senator James Eastland during my confirmation hearings in 1975 in which he made it perfectly clear that he had no hesitation in relying on statements by Senator Edward Kennedy about future committee procedures even though they profoundly disagreed about matters of substance.) Moreover, staff members would not retain their jobs if they were unfaithful to their employers.

The risk that a lobbyist-inspired comment by an individual legislator during a floor debate will have an impact on a judge’s evaluation of legislative history is trivial. But the text of bills is often not self-explanatory, and it is necessary to read committee reports to understand the issues. Katzmann cogently explains how and why those reports play a central role in the law-making process.

Katzmann also discusses the role that administrative agencies play in the interpretation of statutes. They often participate in an ongoing dialogue with Congress, or more narrowly with the committees responsible for the legislation that they enforce. Based on his own study of the work of federal agencies, he has found that they rely heavily on legislative history when discharging their responsibility to draft regulations that have the force of law.

As a result, given the well-settled rule that courts must follow an administrative agency’s reasonable interpretation of an ambiguous statute, a federal judge must approve an agency’s choice between two reasonable readings of an ambiguous provision even if legislative history played a decisive role in the agency’s decision. Thus, in the real world, legislative history has an important part in statutory construction. Indeed, on the Supreme Court seven of the nine active justices rely on legislative history in appropriate cases.

Advertisement

Despite the fact that textualists are in the minority, Katzmann acknowledges that Justice Scalia has led them in a “spirited debate” during the last twenty-five years. In chapter 4 he describes and responds to four arguments favoring Justice Scalia’s approach. To frame the debate he begins with a discussion of the Supreme Court’s 1892 decision in Church of Holy Trinity v. United States, the case that both sides cite to illustrate the differences between them. In that case the Court held that a church had not committed a crime when it paid an English minister to move to New York and become its pastor notwithstanding the plain text of a federal statute prohibiting the prepayment of the cost of bringing foreigners into the United States “to perform labor or service of any kind.”

Those committed to ascertaining the purpose of statutes agree that a literal reading of the text of the statute supported the prosecution; but they submit that the Court’s discussion of legislative history justified its holding:

A thing may be within the letter of the statute and yet not within the statute, because not within its spirit, nor within the intention of its makers.

And the textualists agree that if it were permissible to consider congressional intent, the legislative history demonstrated that the statute was intended to apply only to manual labor. But in their view Congress is a “they” made up of 535 legislators, not an “it,” and legislative intent is thus an oxymoron.

Holy Trinity was a unanimous decision that has been cited with approval by well-respected judges, including Oliver Wendell Holmes. Judge Learned Hand echoed its reasoning in his admonition that “it is not enough for the judge just to use a dictionary.” And after World War II influential scholars at Harvard championed the purposive approach. Katzmann writes:

In contrast to the legal realists of the 1930s, who believed that judges make law, the proponents of the legal process approach viewed judges as agents of the legislature with the ability to discern Congress’s purposes and to interpret laws consistent with those purposes.

Before identifying the four arguments against the use of legislative history, Katzmann explains some of the ways that such history is beneficial and notes that its use is supported by leading legislators from both political parties in both the Senate and the House. He also cites a recent comprehensive study of legislative staff members who view legislative history “as the most important drafting and interpretive tool apart from text.”

Turning to “The Textualist Critique,” Katzmann notes that a sustained attack on the use of legislative history began in the 1980s and has been largely led by Justice Scalia. After quoting several of Justice Scalia’s comments—“We are governed by laws, not by the intentions of legislators…. The law as it passed is the will of the majority of both houses, and the only mode in which that will is spoken is in the act itself…”—he states that the critique has at least four parts.

The first is premised on the Constitution; the second is an argument that the use of legislative history impermissibly increases the discretion of judges. The third is a prediction that Congress would write better statutes if its members knew that judges would not consult legislative history. And the fourth apparently reflects a concern that judicial reliance on legislative history will enhance the influence of lobbyists representing private interests rather than the public good.

While it is true that Justice Scalia has often expressed his concern about lobbyists’ ability to have an input in the creation of legislative history, I have always thought that those comments were merely a part of his broader objection that rests on his understanding of the Constitution. Similarly, it seems to me that a prediction that a judicial refusal to consult legislative history would improve the quality of legislative draftsmanship is not only incorrect, but actually disrespectful to the professionals employed by a coequal branch of our government.

Moreover, the argument that giving weight to legislative history enhances a judge’s ability to impose her views on the law is simply wrong; a duty to consider more guideposts rather than less constrains rather than enlarges the judge’s discretion. Thus, I am persuaded that the most important basis for Justice Scalia’s objection to the use of legislative history rests on his understanding of the Constitution. As I shall explain, I am also convinced that his understanding—though not without support in precedent—is quite wrong.

Advertisement

It is significant that Justice Scalia refuses to join any part of a colleague’s opinion that relies on legislative history. This practice is comparable to that of Justices William J. Brennan and Thurgood Marshall, who would not join opinions in cases involving capital punishment even if the opinions correctly stated the law. They firmly believed that the death penalty was unconstitutional. Justice Scalia firmly believes that legislative power can only be exercised by Congress. If legislative power cannot be delegated to the executive or to an administrative agency, it surely could not be delegated to a legislative committee, an individual legislator, or a mere committee staff member.

In his book Katzmann suggests that Scalia’s position derives its principal support from INS v. Chadha (1983), a case in which the Court held that the legislative veto by one house of Congress was unconstitutional. (In Chadha’s case the House of Representatives, acting on its own, vetoed the suspension of a Kenyan surgeon’s deportation.) Acts of Congress have binding legal effect only when the procedure for enactment specified in the Constitution is followed. While Chadha may provide some insights into Scalia’s views, I think it more likely that Scalia is relying primarily on his own views about unconstitutional delegations of legislative power. In the recent book Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts (2012), which Scalia coauthored with Bryan Garner, they describe legislative power as “nondelegable.”

That characterization is consistent with his statement of a question presented in Whitman v. American Trucking Assns., Inc. (2001). In that case the Supreme Court reversed a lower court’s holding that the Clean Air Act’s requirement that the Environmental Protection Agency promulgate national ambient air quality standards was unconstitutional because, as interpreted by the EPA, the statute failed to provide an intelligible principle to guide the agency’s exercise of authority. At page 472 of his opinion for the Court, Justice Scalia framed the issue in these words: “In a delegation challenge, the constitutional question is whether the statute has delegated legislative power to the agency.” And in his conclusion, he summarized the Court’s holding by stating that the statute “does not delegate legislative power to the EPA.”

In a concurring opinion joined by Justice Souter, I wrote:

The court has two choices. We could choose to articulate our ultimate disposition of this issue by frankly acknowledging that the power delegated to the EPA is “legislative” but nevertheless conclude that the delegation is constitutional because adequately limited by the terms of the authorizing statute. Alternatively, we could pretend, as the Court does, that the authority delegated to the EPA is somehow not “legislative power.” Despite the fact that there is language in our opinions that supports the Court’s articulation of our holding, I am persuaded that it would be both wiser and more faithful to what we have done in delegation cases to admit that agency rulemaking authority is “legislative power.”

It seems to me quite likely that Justice Scalia’s categorical opposition to judicial examination of legislative history is strongly influenced by his questionable view that legislative power is categorically “nondelegable.” Of course, even if it were nondelegable, I would remain convinced that looking at a committee report in order to better understand what a statute means is just as permissible as looking at a dictionary to accomplish the same objective.

Katzmann describes three statutory cases in which he wrote opinions resolving ambiguities in federal statutes. In two of them the Supreme Court endorsed his view and in the third he was reversed.

In Raila v. United States (2006), in which Sonia Sotomayor, who was later to become a justice of the Supreme Court, was a member of the court of appeals panel that heard the case, the judges construed a provision of the Federal Tort Claims Act that shields the United States from liability for injuries caused by “the loss, miscarriage, or negligent transmission of letters or postal matter.” The plaintiff had been injured when she slipped on a package that the mailman had left below her front door. For purposes of deciding whether the government was liable, the court assumed that the postal worker was negligent and that the plaintiff’s injury was caused by that negligence. The case boiled down to interpreting the meaning of “negligent transmission,” a term that was not defined in the statute itself. Disagreeing with the district judge who had held that the government was not liable because the “transmission” of the mail had ended before the plaintiff was injured, the Court of Appeals reversed his decision.

Later the Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit reached the contrary result and the Supreme Court resolved the conflict in an opinion written by Justice Kennedy. Katzmann devotes over twelve pages to an interesting discussion of the plausible arguments on both sides of the issue, ultimately quoting the paragraph in Justice Thomas’s dissent that relies on the dictionary definition of the term “transmission.” The only relevant legislative history made it clear that the government’s waiver of sovereign immunity allowed plaintiffs to recover for injuries caused by the negligent operation of motor vehicles, but those were cases in which the tortious conduct occurred during the transmission of the mail, not after it concluded.

Although Katzmann points out that most judges are neither wholly textualists nor wholly purposivists, two interesting aspects of the case that he does not emphasize support that proposition. First, although Justice Thomas relied primarily on the dictionary definition of “transmission” in his dissent, he went on to make an argument about Congress’s purpose. And despite the force of that dissent, Justice Scalia joined Justice Kennedy’s opinion for the Court.

The second case discussed in the book involved the question whether the phrase “any court” really meant “any court” or just described “any court in the United States.” The term is used in the federal criminal code to prohibit possession of a firearm by any person who had previously been “convicted in any court” of a crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year. The Second Circuit held that a prior conviction in a Canadian court was not covered. In reaching that conclusion, the court first noted that another provision of the statute exempted antitrust violations as a basis for prohibiting possession of a firearm but omitted any exemption for foreign business crimes and quoted statements in committee reports that “strongly suggested” that Congress was concerned only with prior state or federal convictions for violent crimes.

The court also thought that the complete absence of any discussion of the effect of triggering a firearms prohibition on the basis of foreign convictions for crimes that would be treated as misdemeanors here, or foreign convictions following trials with insufficient procedural safeguards, indicated that the legislators had not intended the felon-in-possession ban to apply to foreign convictions. While the Tenth Circuit agreed with the Second, three other circuits did not; hence the Supreme Court ultimately resolved the issue in Small v. United States (2005), a case decided by a 5–3 vote.

The case was argued in our Court on November 3, 2004, and not decided until April 26, 2005, when Chief Justice Rehnquist’s terminal illness prevented him from sitting and I was serving as the acting chief justice. As the senior member of the majority of five justices that had concluded that the Second Circuit’s narrow reading of “any court” was correct, I assigned the writing of the majority opinion to Justice Breyer. Because of his prior experience as chief counsel to the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, he is especially well qualified to identify and explain the intent of Congress in statutory cases.

In his opinion Breyer relied, in part, on the failure of any legislator even to mention the potential problems associated with prohibitions based on foreign convictions, prompting this comment in Justice Thomas’s dissent:

The Court’s reliance on the absence of any discussion of foreign convictions in the legislative history is equally unconvincing…. Reliance on explicit statements in the history, if they existed, would be problematic enough. Reliance on silence in the history is a new and even more dangerous phenomenon.

For this proposition he cited Justice Scalia’s solo dissent in Koons Buick Pontiac GMC, Inc. v. Nigh (2004). In that opinion, Scalia referred to a similar argument as the “Canon of Canine Silence.” That so-called canon was the brainchild of Chief Justice Rehnquist, who had concluded his opinion for the Court in Church of Scientology of California v. IRS (1987) with this comment:

All in all, we think this is a case where common sense suggests, by analogy to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s “dog that didn’t bark,” that an amendment having the effect petitioner ascribes to it would have been differently described by its sponsor, and not nearly as readily accepted by the floor manager of the bill.

Rehnquist had made precisely that argument seven years earlier in his persuasive dissent in Harrison v. PPG Industries, Inc. (1980). Both as an associate justice and as chief justice, Rehnquist wrote many opinions that relied heavily on his analysis of legislative history. His argument that if Congress intended to make a major change in the law, the change would have been mentioned during the lawmaking process seems perfectly sensible to me.

The third case discussed by Katzmann raised the question whether “reasonable attorneys’ fees as part of costs” include expert consultant fees. By a vote of 6–3 the Supreme Court reversed the Second Circuit’s holding that had rested largely on an interpretation of legislative history. The Supreme Court did not disapprove of the circuit court’s reliance on or analysis of that history. Instead, endorsing an argument that had not been raised in the court of appeals, the Court held that, because the case raised issues under the Spending Clause of the Constitution, even if Congress did intend to authorize recovery of those costs that intent had not been expressed in the text of the statute with sufficient clarity to justify imposing liability for expert consultant fees on a local government. The quotations from Justice Breyer’s dissent, which Justice Souter and I joined, confirm my appraisal of his expertise in statutory cases.

Although that was a case in which the Court found that the interest in giving local governments fair notice of their potential liability for costs outweighed the intent of the enacting Congress, it did not present the more difficult question whether a court should enforce plain statutory text even if it is persuaded that the text is the product of a “scrivener’s error.” The experts employed by Congress to draft statutes seldom make mistakes, but given the complexity of some federal legislation, such mistakes do in fact occur. And some of those mistakes produce results that are not absurd. The Court’s 8–1 decision in Koons, involving an interpretation of an obscure provision in the Truth in Lending Act, was such a case. I wish Katzmann’s book included a comment on this category of cases.

Despite that omission, the entire book will provide interesting reading for nonlawyers and reinforce the judgment of the seven members of the Supreme Court who believe that a fair examination of legislative history will help them understand the work of their colleagues in Congress.

This Issue

October 23, 2014

How Bad Are the Colleges?

Find Your Beach